PROFILE: ARNE ANDERSSON

1917-2009

b. Trollhätten, Sweden.

70kg/154lbs 5’10”/1.78

|

| Andersson in his typical position behind Gunder Hägg. Note his muscular physique--unusual for a runner. |

It was a great honour for the 21-year-old Arne Andersson to represent Sweden in the 1939 Finnmark competition against Finland. For his international debut, he had been chosen as the second string to Åke Jansson in the 1,500 after improving his 1938 PB by five seconds with 3:53.8. His role in the four-man race was to help Jansson win by pacing him until the final stages. Jansson, with a 3:52.4 PB, was expected to need help as his two Finnish adversaries, Hartikka and Sarkama, were also 3:52 runners.

Fortunately, the young and inexperienced Swede did not have to do the initial leading as Sarkama (59.3) and then Hartikka (2:00.9) made sure the pace was fast. Andersson, when he heard the 800 time of 2:01 thought the timekeeper was joking: “I was used to a slower time and would normally die under such a pace. Somehow I didn’t, and I still wonder why.” (Cordner Nelson and Roberto Quercetani, The Milers, p.130)

At the bell 300 meters later, Andersson still had the reserves to take over the lead. He ran on, hoping to set up Jansson in the final straight. However, Jansson was having difficulty staying with his pacemaker, and when Andersson looked round to wave his first string through near the end of the race, Jansson wasn’t with him. So the virtually spent Andersson had to keep going. And although he began to fade, he managed to hold his lead to the tape. His time was the world’s fastest of the year: 3:48.8. This time was only one second outside Lovelock’s world record of 3:47.8. Jansson, gaining a lot on his second string in the last 50, finished a close second (3:49.2) and Hartikka was third in 3:50.0. In one race, Andersson had become a world-class runner.

Early Development

A combination of good genes, an active childhood, and five years of running had enabled Arne Andersson to make such a dramatic impact on the world running scene. Andersson grew up Vänersborg, 86K north of Gothenburg and near his birthplace Trolhätten. Like most Swedish children he was always active in outdoor sports. In fact his family were avid sports people; his grandfather had a reputation for being the strongest man in the county. Apart from cross-country skiing, Andersson showed an early aptitude for canoeing and swimming. As a junior swimmer he recorded the best times in Sweden.

He became focused on running at age 16 in 1934, when he spent the summer in nearby Uddevalla training with the local running champion. He won the Swedish school championships in 1935 and 1936. After high-school graduation he attended a training college for teachers and continued running. As a student, he was able to devote several hours a day to training, and this enabled him to improve to 4:04.2 in 1937 and to 3:58.6 in 1938. A consistent training regimen led to his brilliant 3:48.8 in 1939. Soon after this breakthrough, he confirmed his new stature when he gave Taisto Maki a good race over 2,000, losing by less than a second to the current 5,000 and 10,000 WR-holder with 5:21.4.

New Rival

Andersson's 1940 season was not so successful. He lost all three of his major races to Swedish runners. Both Jönsson-Kalarne and Gunder Hägg beat him over 1,500, and Åke Jansson beat him over 2,000. Andersson’s best 1,500 time for the year was only 3:51.0, which was 2.2 seconds slower than his 1939 best.

He began on a high note in 1941, by winning the Swedish Cross-Country Championships ahead of Hägg. Of 27 races in the ensuing track season, he lost only five, each time finishing second. Four of these losses were to Hägg. In fact, a big rivalry was developing between these two fast-improving runners.

His first clash with Hägg led to a very close race, with Hägg winning 3:50.2 to 3:50.4. This set up a much anticipated confrontation in the Swedish championships, with Hägg the favorite after running a fast 3:48.6. Andersson let Hägg follow Ahlsen for splits of 58.8, 63.2. He stayed close as Hägg took the lead and passed 1,200 in 3:03. The 61-second third lap slowed Hägg in the last 300, but Andersson couldn’t get on even terms with his rival. Hägg crossed the line in 3:47.5, with Andersson timed in 3:48.6. No wonder Andersson was unable to get ahead: it was a new world record for Hägg. Andersson’s only reward was a slim PB.

Andersson’s third and final 1941 race against Hägg was over a Mile six days later. Again he was outlasted by Hägg, although the margin was very small: 4:09.2 to 4:09.6. There was some consolation for Andersson three weeks later when he ran the fastest Mile time of the year with 4:08.6. But two years after his big breakthrough in 1939, when he became Sweden 's premier miler, Andersson now found himself relegated to Sweden’s number two. He had to find a way to beat the brilliant front-running Hägg.

Dominated by Hägg

Andersson went through another hard winter’s training while he completed his teacher’s qualifications. His 1942 competitive season started with five 1,500s; after a 3:53.4 and a 3:54.0, he ran an impressive 3:49.0 (0.4 off his PB) on June 16. So on July 1 he must have felt ready and confident for his first encounter with Hägg over One Mile. It was Hägg’s first race of the season, so there was no indication of his form.

|

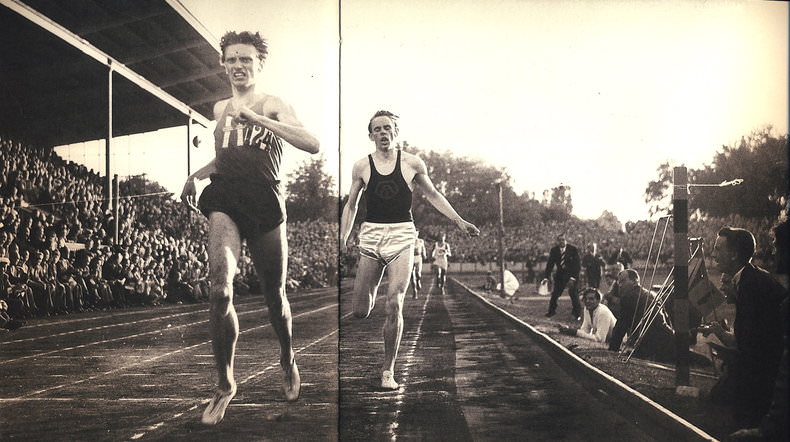

| Hanging on to Hägg en route to a 4:06.4 Mile and second place. |

The capacity Gothenburg crowd saw the early pace of 59.4 set by Olle Petersson. The field went through two laps in 2:01.2. Then the pace slowed a little on the third lap as Hägg led with Andersson close behind. The bell rang at 3:04.8. The two stayed locked together, passing 1,500 in 3:50.4. Andersson moved up to Hägg in the straight and looked the winner. But he was surprised by Hägg’s resistance and was unable to pass. Hägg reached the tape in a world-record time of 4:06.2. The luckless Andersson was timed in 4:06.4, equaling Wooderson’s previous world record. Just as in his last Mile race against Hägg in 1941, Andersson was mere inches behind his rival. Afterwards, he said, “Hägg just flows along. I labour.” (The Milers, p.143)

|

| The finish of the 1942 world-record Mile. |

Two days later, he ran against Hägg over Two Miles, which was not his best distance. It was no surprise that Hägg won this race in 8:47.8 (another world record), but it was a surprise how well Andersson performed with 8:51.4, well under Taisto Mäki’s 1939 WR of 8:53.2. A week later Andersson and Hägg were in Stockholm for a major meet, but this time Hägg opted for the 800. Andersson, on the other hand, set about breaking Hägg’s ten-day-old Mile world record—despite the windy conditions. After being towed through the first two laps in 58.5 and 2:01, he was on his own. Clocking a fraction faster than Hägg’s WR speed at 1,200 and at 1,500 (3:03.5 and 3:49.8), he held on magnificently to the tape, his final time equaling Hägg’s WR of 4:06.2. It was Andersson’s first world record.

Only a week went by before Andersson raced Hägg again in Stockholm, this time over 1,500. Again he faced bad conditions, the track being so waterlogged that the race was run in the third lane. This time he was unable to match Hägg, who despite the conditions ran away from everyone to set a new world record of 3:45.8. Not even Andersson could stay with Hägg after the first 58.0 lap. He ended up fighting with Ahlsen for second place, which he finally achieved in 3:49.2.

Andersson’s next encounter with Hägg was over 2,000, and he performed brilliantly. But again he was beaten by a world-record performance. Hägg clocked a 5:16.3 with Andersson close behind in 5:16.8, which equaled the previous world record. Yet another defeat followed, this time over 3,000. Andersson was only third behind Hägg in 8:11.4. There were now signs that Andersson was a defeated man. While Hägg took some time off racing to recover from an illness, Andersson should have easily won the 1,500 Swedish title, but he could only run 3:51.4 for second place. Thereafter his season wound down with four 800 races and only two 1,500s (3:58.6 and 3:53.2). He didn’t race Hägg again that season, as his rival broke another six WRs and took away the share he had in the Mile world record with 4:04.6.

Training Changes

Despite losing to Hägg every time in 1942, Andersson was not about to give up. It was time to rethink his training practices and to prepare himself to run even faster. His qualification as a teacher and his appointment to Skrubba, a school near Stockholm, led to his meeting Pekka Edfelt, a decathlete with an interest in coaching. Edfelt began to work on Andersson’s running style, which, especially in comparison with the smooth and efficient style of Hägg, was ungainly and uneconomical. The problem of Andersson's style has been described best in The Lonely Breed: “He had so much energy, that was mainly the problem—half of it was being wasted in that huge, bounding stride and wildly flapping arms. He would have to bring his arms in and shorten his stride.” Edfelt trained regularly with him in the forest to help Andersson work on “condensing his stride.” (Ron Clarke and Norman Harris, p.70)

As well as his running style, Andersson also changed his workouts. Now busy as a teacher, he had limited time for training. So his workouts became shorter and more intense. Further, he followed Hägg’s example and trained in the forests. After all the hard work he put in over the 1942-1943 winter, it must have been disappointing for him to learn that Hägg would not be competing in Sweden during 1943, as he had left to race in the USA.

Fastest-Ever Miler

Andersson began his 1943 season with four low-key 1,500s spread over a month—3:52.2, 3:54.6; 3:56.6, and 4:01.0. Then on July 1 at the Swedish Championships in Gothenburg, he ran the Mile. He was given almost perfect pacing by Arne Ahlsen who led through the first three laps in 58.0, 1:59.8 and 3:02.0. Andersson was right behind Ahlsen for the first two laps, but he was a little behind at the bell with 3:03.5. Nevertheless, he managed an unusually fast lap of 59.1 to give him a new world record of 4:02.6, a full two seconds faster than Hägg’s mark. The running-style changes he had undertaken with Edfelt had worked.

It was now a matter of time before Andersson captured Hägg’s 1,500 record. The poor summer weather forced him to wait three weeks. Although he ran three sub-3:50 races in July and early August, it wasn’t until August 17 in Gothenburg that the conditions were right. He was paced through in 58.5 and 2:01, but he had to take the lead on the third lap. Passing 1,200 in 3:00.8 (1.9 seconds slower than Hägg’s world-record pace), Andersson then showed his new-found speed. He ran the last 300 in 44.1 (compare Hägg’s 46.9) to finish in 3:45.0. He had beaten Hägg’s world record by 0.8 of a second.

With Hägg abroad, there was no one in Sweden to give Andersson a good race, so his season petered out with some lower-key races. Near the end of the season he was beaten for the first time in 1943 by Lennart Nilsson over a 1,500 in Ostersund. But his goals for 1943 had been achieved with his two world records. It was now time to prepare to defend them in 1944.

Hägg Defeated

|

| Typical situation: Hägg leading and waitingfor Andersson's challenge. |

Andersson was now busy at his Skrubba school. He spent the whole day with his students and had to fit in his daily training in a small time slot. His workouts were around 7K and involved either straight runs or interval training. In June 1944, after two easy 1,500 wins in 3:58.8 and 3:55.0, he ran a fast 800 in 1:52.8, a solid 1,500 in 3:48.8 and a world’s best 3/4 Mile in 2:56.6. He was certainly ready to meet Hägg over 1,500. Hägg, just as he had done in 1942, had begun his season with a world record, this time over 2 Miles (8:46.4). Needless to say, there was great excitement in Sweden over the first encounter in almost two years between these two record-breakers.

Hägg and Andersson first met over 1,500 in Stockholm on June 28. Hägg, clearly worried about his rival’s improvement, injected a 60-second lap 2 in an attempt to break Andersson early. This didn’t work, and Andersson went on to win clearly in 3:48.8 to Hägg’s 3:50.2. As Bob Phillips has pointed out, this was Hägg’s first defeat in 52 races and his first defeat in 10 races with Andersson. (3:59.4: The Quest for the Four-minute Mile, p.133)

But great champions don’t go down easily, and Hägg’s response came in the next meeting in Gothenburg on July 7. Lennart Strand, the designated pacemaker, took the field into new territory with laps of 56.0 and 60.0. Andersson, perhaps a little jaded from his 2:56.6 3/4 Miles race two days earlier, decided not to follow this fast pace, so Hägg had five meters on him at 400 and still 3.5 meters at 800. Hägg took over from Strand and ran a strong lap 3 with 61.3 for 2:58.0. Andersson managed to catch Hägg by 1,200, but the effort cost him: “I almost felt like quitting. My arms were heavy and my legs [were] like lead.” (Milers, p. 153) He was never able to get on terms with Hägg, who managed to put a full second between himself and Andersson with a 45.0 last 300. Both men broke Andersson’s 3:45.0 record set the previous year: Hägg 3:43.0; Andersson 3:44.0. Andersson had improved since 1943, but so had Hägg.

Mile World Record Again

|

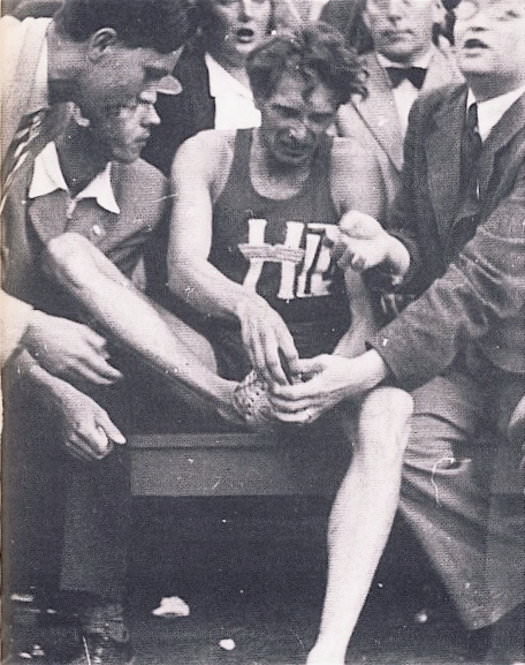

| Andersson's greatest win over Hägg in a world-record time of 4:01.6. |

With public interest in the rivalry reaching fever pitch, the two met a week later in Stockholm. Andersson got his own back this time in a slower race 3:48.4 to 3:49.2. Perhaps because of less than ideal conditions, Hägg didn’t set a fast pace. But there were ideal conditions in Malmo four days later, and the capacity 14,000 crowd created an electric atmosphere for the five runners who lined up for the Mile. The field was exactly the same as the one that ran in Gothenburg eleven days previously. Strand again acted as pacemaker, running the first two laps in 56.8 and 1:56.0, with Hägg and Andersson clocking 56.9 and 1: 56.7. Hägg then went into the lead and passed the bell under 3:00 with 2:59.4. Andersson was in contact a meter behind and stayed there round the last curve, the two passing 1,500 in 3:46.0 and 3:46.1. Then, with his newly-developed speed, Andersson managed to pass his rival in the last 100 and claim a new world record of 4:01.6. It was a brilliant achievement to pass Hägg as the Jamtlander was running a faster Mile than anyone had run before.

Andersson was on the top of the world. To confirm this, Andersson beat Hägg 3:49.6 to 3:50.0 in the Swedish Championships. This was their last race over 1,500 or the Mile in 1944, though they did meet twice more, over 2,000 and 3,000. These were long distances for Andersson, but he beat Hägg both times. Andersson also ran fast times for 1,000 (2:21.9, just 0.4 off Harbig’s WR) and for 2,000 (5:13.2, 1.4 off Hägg’s WR). With a fabulous mile record and six wins out of seven races with Hägg, Andersson could now rightly claim that he was number one. His hard work and careful adaptation of his running form had certainly taken him ahead of the inherently more talented Hägg.

Final Season

It would be easy to say that 1945 saw an anti-climactic end to Andersson’s career. That he over-raced cannot be denied. In the 4 1/2 month track season, he raced 34 times. In his 1,500s he was under 3:50 only five times, with a best of 3:45.0. He ran the Mile six times, averaging 4:06.2. And he won all but four of his races, when he was second.

The main reason for the anti-climax was that Hägg and Andersson avoided running against each other. They met only twice. One of the two encounters was a classic Mile in Malmo on July 17. This race says more about Hägg than Andersson. Hägg was not in his best form after a springtime trip to the USA, and yet he achieved what was probably the greatest performance of his life. His season’s best was only 3:51.4, and his three other 1,500s averaged only 3:59.9. Andersson, on the other hand, had 3:45.0, 3:46.8 and 3:47.0 clockings. Of the three other runners in the Mile, two (Lennart Strand and Rune Persson) were greatly improved and were starting to push Andersson.

|

| Removing the starter's-gun cartridge from his specially sharpened spikes. |

Before another capacity Malmo crowd, Åke Petterson led the field through 400 in 56.2 and 800 in 1:58.5 before dropping out. Hägg then took over and passed the bell in 2:59.7.This was just 0.3 slower than the 1944 WR time when Andersson had won in 4:01.6. The race looked to be Andersson’s, as the in-form runner was running comfortable in Hägg’s wake. But Hägg was inspired. He led through 1,500 in 3:45.0, which was a whole second faster than in 1944. Andersson was right with him in 3:45.4. But amazingly Hägg was able to pull away and hit the tape in a new world record of 4:01.4, 0.2 just under Andersson’s 1944 world record. The gallant Andersson was only 0.8 behind with 4:02.2. Gallant is an appropriate word here, as Andersson ran most of this race with a starter’s-gun cartridge lodged in his spikes. Only those who have run in racing spikes can appreciate how difficult this must have been for him.

After this race, Hägg avoided Andersson, running the 5,000 in the Swedish Championships and generally sticking to longer distances. It was a wise move as he did not break 3:50 for 1,500 in six subsequent attempts. Andersson was not in the greatest of form either, but he was certainly running better than Hägg. Andersson showed his class in two clashes (in London and in Gothenburg) with the great Sydney Wooderson, whose Mile world record both he and Hägg had broken. The plucky Englishman, emaciated after the deprivations of the war ran courageously in both races.

Urged on by his home crowd, Wooderson dogged Andersson for the first three laps of the London race (60.8, 2:03.2, 3:08). Then to the surprise of everyone, the pale Englishman took the lead and held it until the near the finish, when Andersson passed him to win 4:08.8 to 4:09.2. In Gothenburg Wooderson ran even faster. Andersson had a pacemaker for the first two laps (58.6 and 2:00.1) and then pushed the pace to the bell (3:02.8). Wooderson was still right with him and even managed to take the lead with 200 to go. Andersson had to work hard to pass the Briton with 50m to go and won by 0.8 of a second. He was rewarded with a 4:03.4 clocking. This September race was the highlight of the latter part of Andersson’s season, though mention should be made of a fast 2,000 in Oslo (5:13.0), which was close to Hägg’s world record of 5:11.8.

Andersson’s long and busy season came to an end amidst much talk of the illicit money that he and other top Swedish runners were receiving. Although the nominally amateur sport had often turned a blind eye to under-the-table payments by meet directors, the payments were becoming too blatant, and the Swedish authorities were forced to act. In March of 1946 the 28-year-old Andersson was banned for life from competition—along with Hägg and Jönsson-Kalarne. Andersson took this really badly as he had great expectations for the 1948 Olympics. He continued training in the hope of being re-instated, but when the authorities voted on his appeal, he lost by one vote. His competitive running career was over.

Conclusion

Sadly, Andersson’s wonderful career has been overshadowed by Hägg’s. Historians and coaches, while by no means ignoring Andersson, have tended to focus on Hägg for his world records and competitive successes. For example, Robert Parienté’s account of the Hägg-Andersson rivalry focuses entirely on Hägg. (La fabuleuse histoire de l’athlètisme) Still, Andersson’s achievements have been well documented by John Bryant (3:59.4: The Quest to Break the Four-Minute Mile) and by Cordner Nelson and Roberto Quercetani (The Milers). Quercetani wrote elsewhere that Andersson “personified the runner ‘who made himself great.’” (A World History of Track and Field Athletics, p.112.)

The fullest appreciation of Arne Andersson can be found in Norman Harris and Ron Clarke’s The Lonely Breed. Harris and Norman write that they were initially drawn to Hägg’s front-running achievements but that “as we delved into their separate stories our attention began to concentrate on the remarkable Andersson.” (p.67) While admitting that Hägg was the more successful, these authors nevertheless admire Andersson for his “concentration and application” that eventually led to his dominating 1944 season: “Here is a man who suffered a long series of defeats over a number of years, who retained his spirit and enthusiasm, and who gradually harnessed his great energy to produce superb mile running.” (p.67)

Andersson was also harshly treated by some contemporary critics. They criticized him for always trailing Hägg and never doing any of the pacemaking. However, it is clear that this was really Andersson’s only tactical option. Fundamentally, Hägg was a front runner and Andersson was a kicker. Thus in his races with Hägg, Andersson wanted a slow pace where his kick would be most advantageous. Of course, he was able to lead from a long way out, as his 1944 WR Mile showed, but in races with Hägg, leading would have been tactical suicide.

Andersson should be remembered for his competitive spirit, his dedication despite many defeats by Hägg, and his many wonderful performances over 1,500 and the Mile. His PBs were 3:44.0 and 4:01.6, and he set world records for the Mile twice and for the 1,500 once. That he encountered the greatest runner of his generation in his own country only made him better. And despite his intense rivalry with Hägg, he remained the best of friends with him throughout his long life. When an old man he was gracious enough to travel to London to attend the ceremony for the 40th anniversary of Roger Bannister’s four-minute Mile. He must have often thought that he could have beaten Bannister to this landmark had he not been banned from competition.

(Revised and expanded May 2013)

Leave a Comment