PROFILE: EMIL ZATOPEK

1922-2000

The word legendary is overused in journalism, but it is surely an appropriate adjective to describe this great Czech runner. It would also be appropriate to say that he was universally admired and respected. Going to see him race, as hundreds of thousands did, was an unforgettable experience—from his fierce competitive drive to his agonized running style. And although an aggressive competitor while racing, he was the epitome of a gentleman off the track, as many have recounted.

At the heart of his personality was, as his German rival Herbert Schade wrote, “his tremendous willpower.” This innate quality served him well both in training and racing. He set new levels of training, levels that no one had imagined possible. And at the same time he was able to compete with enthusiasm. Not surprisingly legends have developed about his amazing feats.

The circumstances of Zatopek’s early life were hardly conducive to his becoming a runner. Born in 1922, the seventh of eight children in a humble family, he had to start work at 16, in the year that his country was occupied by Germany. He managed to get a research job in the famous Bata shoe company, staying there until 1945, when he joined the Czech army. It was his job that forced him, so the story goes, into entering a race sponsored by Bata. He finished second and within a year was training regularly after work. A deep and intelligent thinker, he gradually adopted the interval-training system pioneered by Nurmi; by the time he joined the military, he had run 3:59.5 for 1,500 and 14:55 for 5,000.

|

Once in the military, he was given more training time and qualified for the 1946 Euros. In the 5,000 final he broke through with a new national record of 14:25, which gave him a creditable fifth place behind winner Wooderson. Afterwards the military accepted him for officer training. By this time, Zatopek was breaking new ground in training loads. He ran in his army boots to save money, claiming they also protected his ankles and developed leg strength. One legend has it that to maximize his training load, he would run on the spot in his boots while on guard duty. Often he had to train in the dark with a flashlight.

Such dedication soon paid dividends. In 1947 he improved his 5,000 time to 14:08 and was ranked #1 in the world. He was also showing himself to be a great competitor, in one race beating the world’s best distance runner and 10,000 WR-holder, Heino of Finland. For his preparation for the 1948 Olympics, he was reputed to have run sessions of 60x400 with 200 rest.

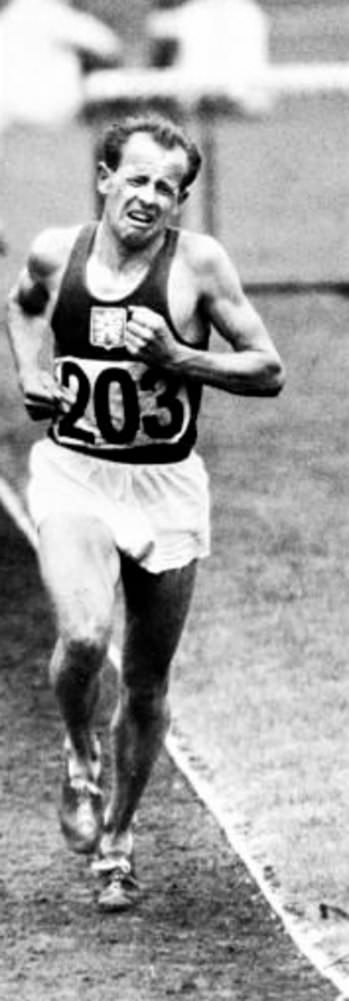

Coming into the Games, he had seasonal times of 14:10 and 29:37. In the 10,000 he was perhaps fortunate that Heino was below par after an injury, but he ran a dominant race, finishing in great style with a huge 47-second margin. (See 1948 Olympic Games) The capacity crowd immediately picked up on his personality, giving him a wonderful reception. In the 5,000, which was not his main event, he did even more to thrill the crowd, making up a huge 60-meter deficit in the last lap to almost catch the winner Reiff. (See Great Races #6) Such was the impact of his last lap that the crowd acted as if he had won.

In 1949 he began setting a string of WR runs. He broke the 10,000 WR, with 29:28.2, which took the record from Heino. But then Heino responded with a 29:27.2 eleven weeks later. After recovering from an injury, Zatopek trained even harder and attacked this record in October. His ability to run to a schedule put him in good stead as he knocked another six seconds off Heino’s record with 29:21.2.

|

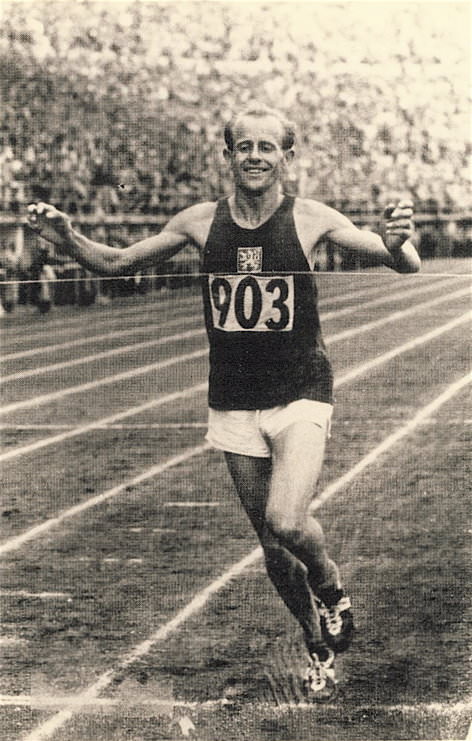

| Zatopek winning his first Olympic gold in London. |

The next year he prepared for a double in the 1950 European Championships. Beforehand, he improved his 5,000 time to 14:06.2 and his 10,000 to a stunning 29:02.6—an 18.6 improvement. But he nearly didn’t make it to Brussels for the championships. First, he got involved in a political row over a young team-mate, Stanislas Jungwirth. Jungwirth had been dropped from the Czech team because his father had spoken out against the Communist Party. Zatopek refused to go unless Jungwirth was reinstated. The party refused to back down, and so did Zatopek. Eventually, Zatopek’s propaganda value won out, the Party backing down. (This incident, of course, is not mentioned in Kotisek’s communist-propaganda biography of Zatopek.) Second, just before the Games he got food poisoning from eating duck and had to have his stomach pumped. Eight pounds lighter, so another story goes, he got up from his hospital bed and went off to Brussels.

He achieved a stylish double in the Euros, cruising to an easy 69-second victory in the 10,000 and then walloping his 1948 Olympic rival Reiff in the 5,000. This time he didn’t let the Belgian get away from him. Reiff led throughout and thought he had a good lead at the bell, but when he looked round for the first time in the race, he saw Zatopek was right with him. A withering burst in the last lap totally destroyed the Belgian, who gave up over 20 seconds to Zatopek in the last lap and collapsed at the finish.

After a training accident that put him in a cast, Zatopek had a relatively quiet 1951 season with a 14:11 5,000. But in the fall, he was looking for more WRs, this time at the longer distances. In two epic runs, Zatopek captured five new WRs. On Sept 15 he set WRs for One Hour (19.558K) and 20,000 (61:16). Two weeks later he improved these for 20,000 (59:18) and One Hour (20.052K) and on the way set a WR for 10 Miles (48:12).

But his unprecedented training workloads were beginning to take their toll. In the late spring of 1952 he became ill after catching a chill. Against doctor’s orders he began to train again. His condition was poor: his first 5,000 was just 14:47, and he could run only 8:48 for 3,000. In his next two races he improved his 5,000 times to 14:33 and then to 14:22 in a Hungary-Russia meet. He ran an encouraging 29:26 for 10,000 in the same meet and then 14:17 and 30:28 to win the Czech championships. Although he was slowly improving with each race, these times did not augur well for the Helsinki Olympics.

In his first Olympic race, the 10,000, Zatopek stayed at the back for the first six laps. Then he led, gradually dropping runners. He went through 5,000 in 14:43. Soon after this, Pirie led for a brief time but then dropped back to leave Zatopek alone with Mimoun. At 8K even Mimoun was dropped, and Zatopek pulled away to a 16-second advantage at the tape. This was his second 10,000 Olympic medal.

|

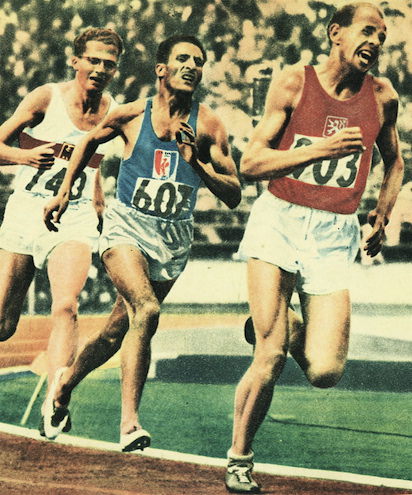

| Zatopek leads into the stretch for his only Olympic 5,000 gold. |

The 5,000 proved to be a much harder race for him (See Great Races #7). Nevertheless, his great competitive spirit came through, and he was able to outsprint three other runners in the last 100. Film of this race shows him digging very deep after almost being left with 200 to go. His final sprint can only be described as frenzied.

With two golds in his pocket, Zatopek now went for an unheard-of third in the Marathon. It would be his third final in eight days—and he had never raced a marathon. The favorite Jim Peters was soon ahead on his own; Zatopek was in a chasing group of five. Jansson and Zatopek were soon broke away from this group, and they passed Peters at 15K. After another 10K, Zatopek dropped Jansson and finished 2:32 ahead of second-place Corno.

He had achieved an Olympic treble, something that is unlikely to be done again—although Viren made a valiant attempt in 1976 in Montreal. Late in the season, just to put the icing on the cake, he added WRs for 15 miles (76:26.4), 25K (79:11.8) and 30K (95:23.8), beating each mark by over a minute.

Again Zatopek’s body broke down. He suffered from pains that “prevented him from walking” and then had to have his tonsils out. There was talk that the 30-year-old’s career was finished. But by late summer of 1953, Emil was racing well again. In Bucharest he won a remarkable race against two Russians: Anufriev, who had broken 14: 00 and got within less than a second of Hagg’s long-standing WR of 13:58.2; and a young runner called Kuts, who had run 14:02. also in the field was the fine Hungarian runner Kovacs. Kuts shot into the lead, while Zatopek ran according to his even schedule. Zatopek caught the Russian at 3K but could not answer another Kuts burst that put him 30 meters ahead. Zatopek kept his head, but with 800 to go he realised he would have to go after Kuts immediately. Kovacs, still with him, was able to hang on for a lap. Emil finally caught Kuts on the back straight of the last lap and passed him on the bend to win in 14:03, equal to his best time from 1950.

Finally, as late as November 1, he attacked his 10,000 WR, managing to lower it by just one second with 29:01.6. On the way he beat Pirie’s six-mile WR with 28:08.4. What had looked like a disastrous season-- and maybe the end of his career--had turned out well after all.

Surprisingly he ran his best-ever times the next year at 31. After standing for ten years, Hagg’s 5,000 WR was beaten four times in 1954. The first to do it was Zatopek, who lowered it by exactly one second with 13:57.2 in May. The next month he knocked over seven seconds off his 10,000 WR with 28:54.2. For three months he held both records—until Kuts, then Chataway and then Kuts again broke the 5,000 WR.

Before those last three WRs, the European Championships were held in Bern. Zatopek was still supreme in his best event, the 10,000, but he was pushed into third and clearly outclassed by Kuts and Chataway in the 5,000.

Sadly, 1954 was his last big year. He ran mediocre times (for him) in 1955. His best 10,000 was 29:25.6, only 8th best in the world. But he was to have one last hurrah: the Marathon in the 1956 Olympics. A groin injury meant he wasn’t in his best shape. Also, he had a hernia operation only six weeks before the race. In view of all this, his sixth place was no mean achievement. When he finished he enthusiastically congratulated his long-time rival Alain Mimoun, who had won the race. It is hard to assess how great a performance his sixth place was in the context of his physical condition.

In 1957, he still won some races, but the 35-year-old was no longer the virtually unbeatable runner of the early fifties. His retirement came the following year. Subsequently he became the patron saint of distance running; many runners, good and bad, young and old, travelled to Czechoslovakia to pay homage to him. They saw in him the epitome of the distance runner. I have met runners who virtually worshipped him.

His later life was rewarding in this aspect, but there were also the political realities. After enduring German occupation in his youth, he had to endure Soviet occupation in his adult life. He coped with it well, although he had to publicly state some anti-western views on occasion. (See YouTube: Emil Zatopek by Andres1956) But when the USSR invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, he became radical. The story goes that he put on his colonel’s uniform and went out into the streets to confront the invading troops. Had he not been the famous Zatopek, he might well have been shot on the spot (Benyo, Marathon & Beyond, May/June, 2001, 34). But his opposition to the invasion led to him being forced to work for seven years in a uranium mine, after which he was considered “rehabilitated” and was given a lower-level clerical job.

Perhaps the most telling story about Zatopek’s character concerns the Australian runner Ron Clarke. In 1966 he invited the Australian to a meeting in Prague and spent a lot of time with him. As they parted he gave Clarke a tiny package, saying, “Not out of friendship but because you deserve it.” Inside the package was Zatopek’s gold medal for the 1952 Olympic 10,000. It had been newly inscribed: “To Ron Clarke, July 19, 1966.” Clearly Zatopek had admired Clarke’s ground-breaking WRs and felt strongly that he was worthy of an Olympic gold medal.

In his later years, Zatopek suffered badly from arthritis. Nevertheless, his celebrity status led to many public appearances. He died in 2000 from a stroke.

2 Comments