Wes Santee Profile

1932-2010

6-0.5 (185cm) 150 lbs (68 kg)

|

With Mile times of 4:01.3, 4:00.6, 4:00.7, 4:00.5 and 4:01.3, Wes Santee came so close to breaking the four-minute Mile. He had been hoping to be the first to break this tantalizing barrier. Then after Bannister ran 3:59.4 in May of 1954, the gifted Kansan hoped to be the first American to do so. Despite many attempts he was still trying in 1956 when he was banned from competition for life over expense violations.

The ban came in the Olympic year of 1956, when he was just 24. His brilliant running over the three previous years had made him a favorite for the Olympic 1,500 title in Melbourne. He had dominated American miling, winning nearly all his races by large margins and setting records galore, including a 1,500 world record. He was also very successful over 800/880, running the great Mal Whitfield to many close races and getting very close to the world record himself. But the chance of Olympic glory was denied him.

The ruthless determination and defiant self-confidence that had enabled him to be such a successful runner turned out to be a double-edged sword, for they also led to serious confrontations with American track authorities. Santee knew he was good, and he displayed a conspicuous athletic ego. “He was his own man,” one of his college team-mates recalled. “He danced to his own drummer. No one could influence him.” This brash, cocky attitude during his competitive years had its roots in a tough childhood, during which he suffered abuse from his father. Finally escaping from home in his late teens, he was able to find the father figure he needed in Kansas University track coach Bill Easton. But even Easton couldn’t keep him out of trouble with the AAU administrators who ran the sport.

|

Santee, like many other top track athletes at that time, was receiving under-the-table expenses. The AAU generally turned a blind eye to such transactions, but Santee’s abrasiveness and outspokenness angered some of the administrators to the point where action had to be taken. After many hearings and court cases, they finally came down hard on him with a lifetime ban.

So in 1956, America’s greatest miler since Glenn Cunningham was history. He left behind an impressive legacy. His best times for non-metric events from Three Miles to 100 Yards were 14:32; 8:58; 4:00.5; 1:48.5; 47.4; 22.2; 10.6. His one outdoor world record was for 1,500m: 3:42.8 in 1954. Indoors he set world records for 1,500m (3:48.3 in 1955) and for the Mile (4:04.9 in 1954 and 4:03.8 in 1955). As well, he won four AAU titles and three NCAA titles.

----

Wes Santee’s childhood abuse is well documented by Neal Bascomb in his 2004 book The Perfect Mile. Bascomb managed to get Santee to open up about his childhood—something according to a close friend he never discussed. Following several conversations with the 70-year-old Santee, Bascomb was able to recount the trauma that Santee endured at the hands of his hot-tempered father, David Santee, who worked a large cattle and wheat ranch near Ashland, Kansas. The Santee family had survived the dust-bowl years of the 1930s in a home without plumbing or electricity. But the worst aspect of Wes’s childhood was the temper of his father: “David Santee dispensed his cruelty with forearm, fist, rawhide buggy whip, or whatever else was at hand—once it was a hammer.” (The Perfect Mile, p. 21) As the eldest of three children, Wes bore the brunt of his father’s temper.

First Race

He reacted in an unusual way. As Bascomb tells it, “Some sons of abusive fathers want to become big enough to fight back; Santee wanted to become fast enough to run away.” (21) And he clearly had a gift for running. In his first ever race, he placed third despite being the youngest in the race. But on returning home afterwards, he had to face the wrath of his father, who had wanted him to stay home and work on the farm.

Fortunately at this point in his life, the first of three crucial substitute father-figures came into the picture. J. Allen Murray, the Ashland high-school coach, believing in the talent of young Santee, stood up to David Santee and even talked him into driving the local runners to meets. After that Santee’s father never interfered with Wes’s running, although his temper didn’t improve. Soon Wes was winning all his races and breaking Glenn Cunningham’s high-school records.

Santee gradually came to realise that his running ability could help him escape from his father. He trained and studied hard, and soon university recruiters were showing interest. All the time, he worked hard on the farm: “I was the workingest kid you ever saw, and one skinny, strong SOB,” he said later. (Wall Street Journal, Sept. 12, 2000) Santee left home at 17, a year before he went to college. Bascomb recounts how one day when father and son were digging six-foot holes for electricity poles, his father started beating him on his back for not working hard enough. This was the last straw. Wes left at once and moved in with a friend in Ashland, some five miles away. Only many years later did he return home just once in an unsuccessful attempt to persuade his abused mother to leave his father.

By the time Wes graduated from high school, he had won two state Mile titles and had broken Cunningham’s national high-school Mile record of 4:24.7. Already he had developed a strong athletic ego. In the school annual in his grad year of 1950 he wrote of himself: “Wes Santee has recently broken the world mile record in the time of 3:58.3, and it should stand for many years to come.” (Len Johnson, The Landy Era, p. 139)

Cowboy on Campus

|

|

Bill Easton at a Santee track session. |

In going to Kansas University, Wes found his second surrogate father figure in his new track coach. Bill Easton was one of the more successful coaches of his era, and he was a typical strong disciplinarian. Well aware of the special talent of Santee, Easton spent a lot of time with him, even having him stay at his home at the start. It is a tribute to Easton's interpersonal skills that he managed with two exceptions, to keep the prickly teenager reasonably happy throughout his university years. A team-mate of Santee had this to say about Easton: “He was a hard taskmaster. I didn’t like Bill; he picked on me. But next to my dad he was the man I respected the most in my life.” (Telephone interview, September 30, 2015)

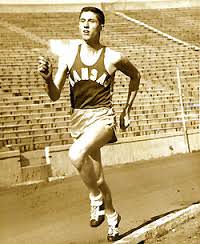

Santee was soon noticed at KU. From the start he flaunted his individuality by being the only student on campus to wear cowboy boots and clothes. But his running was the main reason that people noticed him. In his freshman year he led KU to a Big Seven cross-country title and also helped his squad win the indoor title too. Outdoors he set a collegiate Two Miles record of 9:21.6. At this stage all his early farm work had given him tremendous stamina, so he was performing better at the longer distances. There was little evidence that within two years he would be the second fastest in the world over 800.

So at only 19 he ran the 5,000 at both the Junior and Senior 1951 AAU meets. In the Junior AAU 5,000 he won in 15:03.4 to break Bob Madrid’s 1940 mark of 15:21.7 by a huge margin. The next day he ran in the Senior 5,000 and finished second in 14:52.4, just 4.9 seconds behind the winner Fred Wilt. This was a remarkable achievement for a teenager.

First Tour Abroad

These two runs earned Santee a place on an AAU team that toured Japan in the summer of 1951. Within four weeks he ran seven races winning three 3,000s and placing second in 1,500 and 5,000 races. His best times were 3:59.5 for 1,500 and 8:44 for 3,000. There were no PB breakthroughs, but the competition provided a lot of experience for the freshman. Perhaps the most valuable aspect of the tour was his rooming with Olympic gold medalist Mal Whitfield. More than seven years older that Santee, and with experience that went back to before the 1948 Olympics, Whitfield was a natural teacher, as his later work in Kenya showed, and he became yet another father figure for the young Kansan. Their friendship continued well past this Japan tour, and two years later in 1953 they ran the two fastest 800 times of the year in the same race.

Santee returned home from Japan in August and told his local paper, “I want to make the Olympic team and go to Helsinki, Finland.” (Daily Kansan, October, 2, 1951) In little more than a year he had transformed himself from a high schooler with prospects to a potential Olympic runner.

Rising Sophomore Star

But his first loyalty was to his KU athletic scholarship. And after a steady winter’s training, he moved up to a new level in the spring collegiate competition. At the Drake Relays he showed he had improved his speed a lot over the winter, running two impressive relay anchor-legs over a Mile on consecutive days. First he took over 40 yards down on top college runner Joe La Pierre and caught him just before the tape with a dazzling finish. This effort was timed at 4:06.7. The next day in a similar situation he made up 50 yards and won by 50, clocking 4:07.4. and 4:08.3 on two watches. Thus within two days he had run times, albeit from a flying start, that would have been among the eleven best in the world the previous year. Soon after he ran 4:08.8 race in a dual meet with Kansas State University.

|

|

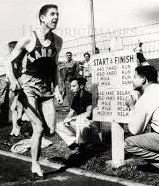

Winning his first AAU title comfortably.

|

So the Olympic year heralded a rising American star. The question now was how he would fare against top American competition in the NCAA and AAU championships. The NCAA went really well for him. Despite his successes over the Mile in the collegiate season, he still saw himself as a 5,000 runner. And he showed everyone why he thought so, beating the NCAA record by 18.2 seconds and winning from Capozzoli in 14:36.3. An improvement of 16.1 on his 1952 AAU time, this time made him the fourth fastest American ever. “I could have cut many seconds off this particular race,” he told reporters afterwards, in typical Santee fashion.” (Milers. P. 196) He was also an impressive victor in the AAU championships, but this time over 1,500. The crowd was abuzz after he opened up a gap of 20 yards on the last lap to finish first in 3:49.3. This was the fastest US time in 12 years, despite a slow start. Santee showed great authority, taking off with two laps to go and running 61 and 59.8 laps. With these two big wins, Santee had earned the epithet “brilliant distance runner” in the New York Times. (June 27, 1952)

Conflict at the Olympic Trials

With consecutive wins in the NCAA and AAU, Santee was one of the favorites in the US Olympic trials a week later. With his habitual self-confidence he planned to compete in both the 5,000 and 1,500. Unfortunately, some of the American track authorities didn’t think that doubling in two arduous Olympic events was in the best interests of the 20-year-old Kansas sophomore. Their subsequent action during the Olympic trials affected Santee profoundly and was the start of his many disputes with the AAU. First, all went smoothly in the 5,000, where he finished second in a PB 14:32, behind Curt Stone (14:27.3), and in front of Capozzoli (14:43.9). After Santee had taken the lead with two laps to go, Stone took over with half a lap later. Santee challenged him on the final bend but then fell back and jogged in, content to take second place and conserve energy for the 1,500.

Assured of an Olympic berth, he lined up for the 1,500 trial, now thinking that this shorter event was really his best chance of an Olympic medal. But just before the field went under starter’s orders, two officials grabbed Santee by the arms and told him he wasn’t going to be allowed to race the 1,500. Not surprisingly Santee was livid. Unknown to him, his coach had been arguing with AAU officials--to no avail--for an hour. As the 1,500 field started without him, Santee was told by Easton: “They’re saying you’re not good enough to run both races, and they won’t let you drop out of the 5,000 to run the 1,500.” (Bascomb, p.27) Years later Santee explained, “There was nothing in the rule book to cover that. It was a purely arbitrary decision.” (Dick Lipsey, “Almost a Sports Immortal,” Associated Press, 1997)

To show the AAU that he was the best American over 1,500, he trounced two of the Olympic 1,500 American entrants (Bill Ashenfelter and Druetzler) in a ¾ Mile race in New York just before the trip to Finland with 2:58.2. Still, he must have gone to Helsinki with a lot of conflict in his mind. It’s impossible to measure the psychological damage that had been done to him at the trials. One indication of his alienation from the AAU can be found in a pre-Olympic news story. For a team workout in Helsinki, a clearly alienated Santee was the odd man out: “The American athletes worked out in jerseys that had ‘US--Helsinki--1952 on them, except Wes Santee of Kansas, who used his college track suit of orange-red pants and blue jersey.” (New York Times, July 9, 1952)

Olympic Reality

In his Olympic 5,000 heat Santee clearly ran to the best of his ability, but the 20-year-old had no idea of how to negotiate an Olympic heat that was full of runners he didn’t know. His coach Bill Easton was back in Kansas, and there was no team support for him; he was on his own. According to Neal Bascomb, he therefore took the initiative and consulted Fred Wilt, an experienced international runner who had finished fourth behind him in the trials. Wilt suggested that Santee should follow the German Schade. Herbert Schade, in fact, was one of the favorites for a medal and, unknown to Wilt, had plans to run a fast heat in order to earn a psychological advantage of his main rivals, Zatopek and Mimoun.

At the start of the 5,000 heat, Schade was soon in the lead. Santee, following Wilt’s advice, stayed close to the German. Soon the two of them were well clear of the field. They passed 3,000 in just over 8:28, having passed 1,500 in 4:06.6. Santee, with a 5,000 PB of 14:32, was running close to 14:05 speed. Not long after the 3,000 mark, the inevitable happened: Santee blew up. His last six laps averaged 81.5, and he finished 13th out of 14 in 15:10.

It was an intensely humiliating experience for him. But the team management was really to blame for the disaster. No wonder Track & Field News reported that Santee “ran like a novice.” (August, 1952) Some informed guidance—like running in fourth or fifth and using his speed at the finish--might well have led to him qualifying for the final. He would have needed to run faster than 14:26.8 to qualify, only 5.2 seconds faster than his US Trials time, when he had eased up in second. In the final, 14:23.6 earned sixth place.

|

|

Following the Olympics, Santee easily wins the British Games Mile in 4:12 on a flooded track. |

If this humiliation in his 5,000 heat wasn’t enough, Santee witnessed two US runners, whom he had beaten handily in the AAU 1,500, reach the Olympic 1,500 final. One of the two, McMillen, ran a brilliant final to earn the silver medal with a 4.1-second PB in 3:45.2. No wonder Santee later asserted he could have won the Olympic 1,500 gold medal.

Santee ran really well in three post-Olympic races while over in Europe. He was unbeaten, running a fast 1:51.2 for 800 and winning the British Games Mile in 4:12.2. He also ran in a 4xMile relay in a match between the British Empire and the USA. On his leg he was chased by John Landy of Australia. Although losing some ground, he was not passed.

The Olympian Returns Home

Once back in Kansas, he was soon competing again. After leading his university team to a cross-country conference victory in November, he was game enough to show his fraternity friends what a great runner he was by accepting a challenge from 28 of them. They were each to run a relay leg of half a mile against him over 13+ miles of road. Santee took the lead from the start and was 400 yards ahead at the end. This fraternity challenge was covered by national media.

Overall, 1952 had been a great year for Santee, but it had been marred by some undeniable failings by the American track officials. At least his experience at the Trials had motivated him to prove himself. Santee was good at putting adversity behind him and moving on. This quality was evident late in his life when he never dwelt on his traumatic childhood nor on all the troubles with the AAU that led to his lifetime ban.

Junior Varsity Runner

Santee was undefeated in the 1953 indoor season. His speed and fitness were evident at the end of February in the Big 7 conference final. After breaking the 880 record in the heats with 1:52.2 on the first day, he won the final in 1:53.6 and the Mile in 4:08.3 the next day. Outdoors he continued to impress. In the Texas Relays a month later he was clocked in 1:49.4 for an 880 medley relay leg. The next day he ran a PB 4:06.7 Mile and then a 1:51.9 relay leg. More amazing doubles followed: 4:06.3 (beating Cunningham’s collegiate record) and 1:50.8 at the Big 7; and 4:07.4 and 1:54.5 at the Missouri AAU meet.

Despite all these fine runs for his university, Santee became unhappy when his coach occasionally insisted that he run yet another relay leg when his effort would make no difference in the team competition. He usually had to make up lots of ground on his relay legs, and he was happy to run his heart out if the effort was going to mean something in the team competition. Matters came to a head at the Drake Relays when he was forced to run the last leg in a relay when Kansas was already half a lap behind. After running his leg, he refused to talk to his coach. In a subsequent meet, after running his races as planned he flatly refused to run an extra race (440 leg) for his coach. Only after his teammates begged him to run did he change his mind; he burned a 47.4 leg. Soon after, his good relations with Easton resumed after a serious discussion.

Santee the Miler

Amazing though these doubles were, they were nothing to compare with his Mile at Compton on June 5. In this race he was up against international competition for the first time in 1953: Reiff of Belgium (4:02.8 in 1952) and Johansson of Finland, who had recently run 4:08.6. Santee followed Reiff through laps of 62.7 and 62.5, and there were murmurs of disappointment in the crowd over the slow 880 time of 2:05.2. Nothing changed until the back straight of lap 3 when Santee jumped the field. He completed the third lap in 58.2, which after a slowish first half of the lap indicated he was really moving at the bell (3:03.5). Only Johansson made an effort to respond. And although this burst eventually took its toll on Santee, he still managed a last lap of 59.1 to clock a wonderful 4:02.4, almost a four-second PB. As Nelson and Quercetani wrote, “His last 880 in 1:57.1 and last three-quarters in 2:59.5 were unprecedented.” (The Milers, p. 196)

All of a sudden Santee had graduated from being a promising American middle-distance runner to a world–class miler with a good chance of being the first to break 4:00. The New York Times featured him, emphasizing his western roots and his student status. The accompanying photo was captioned “Dons cowboy boots to complete western garb before going to classes.” (June 17, 1953)

|

|

Santee wins his second AAU 1,500 title in 4:07.6. |

In his next major meet, the NCAAs, Santee showed that his Compton time was no flash in the pan. In uncomfortably hot weather, he won by 25 yards in 4:03.7, again making his move on the third lap (59.5, 2:04.2, 3:04). Forty minutes later he took the 880 title in 1:50.8. Santee had now been competing at a high level for almost five months and he was reported to be “plain tired out” and 5 lbs underweight. But he was still in good form for the AAUs ten days later. He used his new tactic yet again, bursting away with 700 yards to go and winning by 30 yards in 4:07.6. Stating the obvious, the New York Times asserted that there was “no doubt of his superiority.” (June 28, 1953) Fred Dwyer, who finished second to him in both the NCAA and AAU Miles, 25 and 30 yards back respectively, would no doubt have agreed.

Europe Again

Right after the AAU meet, Santee began an AAU-sponsored European tour. He was now, together with Bannister and Landy, one of the three main prospects to break the four-minute Mile. Landy had completed his track season in Australia with a 4:02.1 best, suffering like Santee from a lack of competition to push him to faster times. Bannister had recently tried twice to run under 4, first clocking 4:03.6 and then 4:02.0. With Bannister knocking at the 4-minute door, could Santee, after a hectic varsity season, get there first?

Still acclimatizing, he first ran two 1,500s in Helsinki, winning the first (3:50.8) and placing second to Johansson in the other (3:50.6). His first impressive performance came two weeks later in Turku, Finland. With his good friend Mal Whitfield, he ran a fine 800, finishing close behind the Olympic champ. Whitfield clocked 1:47.9 and Santee 1:48.9.

With Bannister running fast Miles close to 4:00, promoters in Stockholm set up a 4:00-Mile attempt for Santee. He won the race but clocked only 4:06.6. Two days later on July 23 he set an American record for 1,500 in Gothenburg. For once he had great competition: Sune Karlsson, who broke away from Santee early in the race, lapping in 57.5 and 1:57.5. The Swede was ten meters ahead of Santee at 1,200 (2:58.4). Then Santee started to gain; this situation must have reminded him of his many anchor legs for KU when he would chase down opponents. Santee caught Karlsson coming into the final straight, but Karlsson fought back and Santee only just managed to get ahead at the tape. They both shared the same 3:44.2 time, which was an American record for Santee and was the fastest time in the world for 1953. Interestingly, this was one of the few races in his career that Santee won in a tight finish.

Santee continued racing in Europe every few days until August 26. His program certainly wasn’t organized to help him break 4:00; he ran too many races and hardly any over a Mile. In a total of eleven races, he won seven. His best performance came in an 800 in Oslo where he clocked a 1:48.4 PB behind Whitfield (1:47.9). These times were the two fastest in the world for 1953. This was a surprising time for Santee as he was clearly getting very tired. His other three losses were to top-class runners and were also close races: a 1,500 loss to the German Olympic silver medalist Werner Lueg (3:52.4 to 3:52.6), a Mile loss to Gordon Pirie (4:06.8 to 4:07.2) and a 1,500 loss to Eriksson of Sweden (3:48.2 to 3:48.6).

Troubles off the Track

During this tour Santee was involved in an incident occurred that would have serious ramifications. As he toured Europe, he was fully aware that he was helping to draw in big crowds for his races, and he grew increasingly annoyed at the way he was treated by officials and promoters, feeling he was being exploited and short-changed on expenses. When trying to negotiate a deal on all the prizes he was getting, he felt misled by a German official and lost his temper. He called the official a liar and refused to run another race in Germany. This incident was reported back to the AAU and was used against him later on.

|

| KU Pride |

On top of this, a major article appeared in the Saturday Evening Post (26 September, 1953): “Sure I’ll Run the Four-Minute Mile” by Bob Hurt. After a lot of material on Santee’s ego (“supreme confidence,” “big talk,” “cocksureness”) and his racing career, Hurt wrote about Santee’s opportunity to “cash in after his graduation next June,” when he would have “an easy job” and “ spend the rest of his time running and cashing generous expense-account checks.” Hurt left his readers with the presumption that all top runners were making good money, despite the supposedly strict amateur rules. He wrote that Glenn Cunningham in the 1930s and 1940s “collected enough ‘expenses’ for a down payment on a farm.” Although Santee wasn’t quoted directly on expenses, this article had a great impact on the AAU attitude toward him. He was clearly challenging their authority.

It had been a momentous year for Santee. He had now established himself as an 800/1,500 runner rather than a 5,000 runner. In the 1953 world rankings he was second in the 800, first equal in the 1,500 and third in the Mile. Together with Bannister (4:02.0) and Landy (4:02.1), he had become one of the three favorites for breaking the 4:00 Mile. The next fastest milers, Johansson of Finland (4:04.0) and Karlsson of Sweden ((4:04.4), were not yet seen as potential 4-minute milers.

Back to KU

Although Santee had argued with his university coach over the excessive number of relay legs he was required to run, it should be stressed that overall he made a massive contribution to the Kansas University team on both the track and country. In the fall of 1953, he had little time to recover from his European tour before he was asked to perform in the collegiate cross-country season. After winning at least three races, he took the NCAA cross-country title and helped his team win the national title. On the last day of 1953 he ran an impressive 4:04.2 in the New Orleans Sugar Bowl, winning by 30 yards and clocking 55 for the last lap. The extra training he was now doing with Coach Easton was clearly paying dividends.

While he was getting himself ready for the 1954 indoor season, he was told by the NCAA that because he had run in the AAU for KU in his freshman year (1950-1), he was not eligible for the NCAA national outdoor meet. This ruling did not affect his running indoors, but it was clearly a sign that the track authorities were intent on asserting their authority over him. He started his indoor season with two impressive same-day doubles (4:09/1:53.4 and relay legs of 4:02.6/1:51.8). The 4:02.6 Mile relay leg was a full 2.7 seconds under Dodds’ indoor world record, but obviously couldn’t count as a record. He did beat Dodd’s mark two days later with 4:04.9. However, his time was not accepted by the AAU as it was run on an indoor cinder track rather than on boards. He tried again on boards 10 days later but could manage only 4:06.5. And there was more bad news for him from the AAU: he was banned from foreign competition for a year. The reason given was “breaking training and curfew rules.”

|

|

Santee anchoring Kansas University to yet another relay record. |

Outdoors he was in great form from the start. In the Texas Relays he was clocked in a fast 880 relay leg between 1:47.7 and 1:48.3, and the next day he ran a 4:05.8 relay leg. A week later in Berkeley he ran 4:05.5, 1:51.5 and then a 48.0 relay leg. Still in April, he ran 4:03.1 at the Kansas Relays (58.6 last lap) and two hours later a 4:12 relay leg. He was certainly in good enough form to break 4:00, but the busy collegiate season took precedence and never let him taper for a serious four-minute Mile attempt.

Such were the demands of his Kansas team that he could only take a one-day honeymoon after marrying Danna Denning. His team needed him to be ready for the important Drake Relays. And he did his job there, running 1:49.8 and 4:24 relay legs on the first day and a 4:07.4 anchor on the second. A week later he had an argument with an official when he was told off for coaching a teammate from the sidelines during a race. Santee complained to the press that the official had upset him before his own race.

Bannister Does It

A few days later, the news came the Roger Bannister had run a bona fide 3:59.4 Mile. Santee, who was waiting for the college season to end so that he could make a serious attempt on the 4:00 barrier, made a respectful comment to the press: “Of the ones capable of running a four-minute Mile, Bannister was the one I would just as soon see run it.” (New York Times, May 7, 1954) But he did offer an excuse to the University Daily Kansan: “Having to compete for the university, I’ve run everything from soup to nuts. I haven’t been permitted to concentrate.” (May 7, 1954)

Still, Santee was in the best form of his life and the open track season was ahead. He could now choose his races, rest when he needed to and not have to run two or three races in a day. Could he now break the 4:00 barrier? It would still be a great achievement to be the first American to do so.

1,500 World Record

Santee wisely waited five weeks before his first serious attempt. Somewhat recovered from the grueling collegiate season, he chose a race in Kansas City, where his teammates could help with the pace. They did a good job for him, pulling him through three laps in in 58.0, 2:00.2 and 3:02.0. However, he could not quite run the needed sub-58 last lap. He did manage a 59.3 and equaled Gunder Hägg’s 4:01.3 world record that Bannister had recently broken. Santee was now the equal-second-fastest miler ever.

Following this he went to California to race the Compton Mile. He was confident that the fast track and the warm weather would enable him to run faster than 4:01.3. But there was another pressure looming: now that his university days were over, he was due to do his military service. Compton was one of two chances to go sub-4 before he had to report for duty.

Unfortunately there was no real competition for him at Compton. The initial pace had been good: 58.1 and 1:58.7. But Santee had to take the lead halfway through the third lap and run the rest of the race on his own. He passed the bell in 2:59.0, the fastest he had ever been at this point. He reached 3 ½ laps in 3:28.7, which was 1.8 seconds faster than Bannister had been at this point. He passed 1,500 in world-record time: 3:42.8. But the effort of leading took its toll, and he could only manage a 61.7 last lap. He had run his best time, 4:00.6, but still didn’t break the 4:00 barrier. Tying up in the straight, he could only manage the last 120 yards in 17.8 (4:21 Mile speed) His 1,500 world record was welcome, but it was not what he really wanted.

Santee was running so well that the next day he handed Mal Whitfield his first defeat in three years with a 1:50.0 over Whitfield’s favorite 880 distance. This fine run increased Santee’s expectations for what would be his last chance of the year—a Mile in Los Angeles against the Olympic 1,500 Champion Josy Barthel. Again there was ideal pacing for Santee: 59.5, 1:59.5, 3:00. At this point, Barthel took the lead and maintained the pace into the back straight. Then Santee stormed by. He held his form into the final 100, but then, as he had done the week before, he slowed, unable to complete the last lap in under a minute. It was another close call: 4:00.7. Despite Barthel’s perfect pacing, he still couldn’t break the barrier. “I tied up coming of the curve,” he said afterwards. (Seattle Times, Nov. 14, 2010) Santee had now run three of the five fastest Miles of all time.

Military Duties

A week after his 4:00.7 he was competing as a Marine Corps soldier in inter-service meets and doing his basic three-month military training. He ran 14:19.3 for Three Miles and 4:12.1 for the Mile in late June. Arrangements with the Marines must have been made for him to stay in top running condition, because at the end of the year he was talking to the press about breaking 4:00 at the December 31 Sugar Bowl meet in Florida. As it turned out, the meet was postponed because of rain. The race was run three days later on a sodden track. , which slowed him to a 4:14. Another planned sub-4 attempt in LA for January 16 was cancelled, rain again being the reason.

1955 Indoor Season

The Marines allowed Lieut. Santee to compete regularly in the 1955 indoor season. This time he had some really good competition from American Fred Dwyer and the Dane Gunnar Nielsen, who had run 3:44.4 outdoors in 1954 and had a 4:04.8 Mile to his name. In his first race on January 21 in Washington, Santee was surprised by the Dane’s speed. After a slow 2:12 at 880, Santee took off and covered the next 440 in 60 seconds. Nielsen stuck with him and made his move on the back straight of the last lap. Santee had no answer and was soundly beaten by 15 yards. Nielsen’s time was 4:09.5.

Santee reacted strongly to this rare defeat. In front of a capacity Boston crowd a week later, he not only destroyed Nielsen but also improved his Indoor WR from 4:04.9 to 4:03.8. Still wearing his KU vest, he lapped in 57.6, 2:00.3 and 3:02.1. At this stage, while Nielsen was already dropping back, the crowd realised that the WR was a possibility. Urged on by the noisy Bostonians, Santee almost maintained his speed with a last lap of 61.7. His margin of victory was reported as 32 yards.

|

|

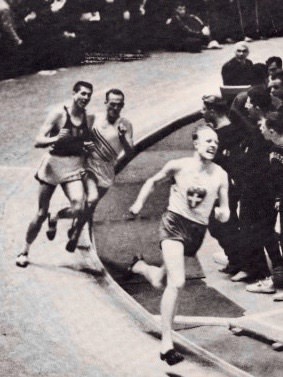

Millrose Games, 1955. While Nielsen sprints to victory, Dwyer tries to pass Santee on the inside. |

The duel continued the next week at the Millrose Games in New York. Nielsen’s response was magnificent: a new world record of 4:03.6. The last lap has been described by spectator Howard Schmertz: “At the end of the back stretch as the tiring Santee veered out in a vain attempt to hold off Nielsen, Dwyer, trying to catch Nielsen, attempted to pass Santee on the inside. As Dwyer came abreast of Santee, Wes moved in, forcing Fred off the track and into the infield. Dwyer, unable to regain the track, ran the last turn in the infield and at the head of the stretch came back on the track ahead of Santee. In frustration, Santee grabbed Dwyer’s shoulder and Dwyer wrapped his arms around Santee’s waist. To the amazement of the crowd, the two pirouetted down the homestretch.” (“My Most Memorable Millrose Moments,” http://www.millrose-games.com/2007/10moments.shtml) Dwyer was disqualified and Santee was given second place. But Santee felt bad about the disqualification and returned the second-place medal to the organizers. Dwyer got his revenge at Madison Square Garden the next weekend: he beat both Nielsen (2nd) and Santee (3rd) in 4:06.2.

The final showdown was in the AAU Indoors on February 19. This time Santee used a fast finish to win the Mile title in 4:07.9 from Nielsen and Dwyer. He was 3-4 yards off the pace with 120 to go, but finished with a three-yard winning margin. In their five clashes, Nielsen had beaten Santee in three of them. The Marine Lieutenant was running well, but he was no longer improving.

Another controversy now arose over the Pan-Am Games to be held in March in Mexico City. Santee originally said he couldn’t get leave from the Marines. However, after some behind-the-scenes arrangements, he was suddenly on the US team after all. In the 1,500 final he was surprisingly beaten at the tape by an unknown Argentine Juan Miranda in 3:53.2. Santee challenged Miranda all the way down the final straight, but he just couldn’t get by. “I don’t know what was the matter,” he said later, perhaps having been affected by the altitude. “My legs pooped out.” (New York Times, March 19, 1955)

Closest Yet

|

| Another indoor victory |

Returning home, Santee ran 4:04.6 and 4:04.2 indoors in Cleveland and Chicago. These two victories completed his 1955 indoor season and suggested he was rounding into top form. This was evident in his very first outdoor race of 1955. On April 2, at the Texas Relays, he went for the 4:00 Mile despite the windy conditions. His Kansas team-mate Art Dalzell did a wonderful job pacing him through the first three laps in 59.2, 2:00, and 3:01.0. But yet again Santee couldn’t quite find enough in the last lap. It was a PB, but it was 4:00.5.

This was the closest he came to breaking the 4:00 barrier, despite remaining unbeaten in 13 Mile races that summer. He was again American AAU champion, beating Dwyer and Seaman in a slow tactical race (4:11.50) His most impressive run was a 4:01.2 Compton win over a fast-improving Bobby Seaman (4:01.4). The race was set up for a sub-4 attempt, with Jim Terrill doing the pacemaking. He did well with 58.3 and 2:00, but then slowed. It took a while for anyone to react. Finally, Fred Dwyer rushed to the front. But the bell time was only 3:03. Santee finally took the lead on the back straight and managed a fast 58.2 last lap, holding on while Seaman made up a lot of ground on his over the last 220.

Suspension Problems

Despite all his troubles with the AAU over expenses, Santee was still thinking ahead to the Melbourne Olympics. But a major setback came in October when he was handed a “permanent suspension” by the Missouri Valley AAU at a secret meeting. After this, he told the media “I would hate to miss the Olympics.” Santee had the right of appeal and a meeting was held for this in November, 1955. He was reinstated on November 30, but right after this the AAU announced that it was going to explore his expenses. The next day he had a discussion with the US Olympic Committee. Despite all the stress and despite his being in the Marines, he showed reasonable fitness soon after his reinstatement, running 4:10.2 in an AAU Mile handicap and then an outdoor 4:06.3 Mile at the year-end Sugar Bowl meet.

As if his life was not complicated enough, Santee suffered a calf injury just before the 1956 indoor season`. He had to drop out of a ¾ Mile race set up especially for him. He also withdrew from the Knights of Columbus meet and the Washington Capital Games.

Finally on Jan 28, he raced a Mile in Boston. It was a rude awakening because there was a brilliant new runner on the scene: Irishman Ron Delany. Santee took over the lead soon after the halfway point and was still at the front at 1320 in 3:03.6. He held the lead until the last lap but then faded badly. Santee (4:08.8) ended up fourth behind Delany (4:06.3), Len Truex and Deady. After he told the media, “I’m short of condition after nearly a month of nursing a pulled calf muscle. I’ve had no sprint work and knew I couldn’t sprint with Delany.” (New York Times, Jan. 29, 1956)

More Problems

The next months were taken up with the struggle between Santee and the authorities. Apart from the AAU, both the Missouri and California AAU branches were also involved. On February 20 the AAU announced that Santee was banned, that anyone who raced against him would be “jeopardized” and that any organization that allowed him to compete would lose AAU sanction. The battle was on. Kansas Senator Frank Carlson publicly attacked the AAU for being “cruel and unfair” to Santee. Even Olympic boss Avery Brundage spoke out in support of the AAU. A Supreme Court injunction nevertheless allowed Santee to race again. In March he won three Mile races in 4:13.8, 4:10.5 and 4:06.9. Then the injunction was discontinued. Santee could no longer race, but William and Mary University, in defiance of the AAU threats, allowed him to compete. He won the 880 in 1:58.2 and the Mile in 4:12.3.

Santee then challenged the AAU head Dan Ferris, alleging that Ferris himself had once paid Santee illegal expenses. Events continued to unfold in May: the AAU banned William and Mary University for allowing Santee to compete, Senator Carlson demanded the ban on Santee be lifted, and the New York State Supreme Court upheld the AAU ruling. This ruling meant that Santee could not compete except in military events. He was still running well. At the end of May he won an 800 in an impressive 1:49.5. There was one more controversial incident in his running career when he was disqualified for impeding in the Inter-Services Championships 800. However, he did win the 1,500 in 3:47.3.

But that was it. Released from the Marines after his two years of service, he no longer had anywhere to compete. His career was over at 24. Amateurism still ruled the sport. Indeed Avery Brundage was soon to propose that every Olympic participant should commit to never becoming professional.

Later that year, Santee wrote an article for the popular Life magazine arguing that amateurism in American track was a sham. He started with the following: “Last year I was offered—and was given—more than $10,000 for running the Mile with no more initiative on my part than answering the phone and accepting the promoters’ offers of expense money.” (Life, November, 19, 1956) No one in the know denied that under-the-table expenses were paid regularly. Clearly the outspoken Santee had been put in his place to maintain the official amateur status of American track. It has been persuasively argued that this amateur status was being reinforced with renewed vigour in the 1950s because of the Cold War. Joseph M Turrini has written that there was a need to “sharpen the AAU ideology” to counter the USSR’s “involuntary, state-financed and state-controlled athletic system.” (The End of Amateurism in American Track and Field, University of Illinois Press)

So Santee, like Nurmi, Ladoumègue, Hägg, and Andersson before him, was lost to track prematurely—thanks to the strict enforcement of amateur rules. We can only surmise what would have happened in the Melbourne Olympic 1,500 had Santee been in the field.

Conclusion

Following Cunningham (1930s) and preceding Jim Ryun (1960s), Wes Santee was the dominant American middle-distance runner in the 1950s. (And all three were Kansans!) Not only did Santee win almost every race he entered on American soil, but he usually won by huge margins. Often the dramatic way he won his races captivated spectators. In fact, many attended meets just to see him run.

Santee was also a record breaker, even a world-record-holder at perhaps the most popular distance—the 1,500. But sadly he will be remembered mainly for the world record he didn’t break—the Mile.

Why didn’t he break the 4:00 barrier? Of course, there’s no simple answer. Based on his five races within 1.3 seconds of 4:00, most commentators agree that he was physically capable of running in the 3:50s. Further he had the confident personality of a good competitor. But he reached the bell so many times with a chance of getting under 4:00, that some have wondered whether there was some weakness that always led to a disappointing last 440. Was there something psychological that affected him when he ran the last lap knowing he was in with a chance? Was there some deep psychic fear that arose out of his childhood abuse? It’s an intriguing question, but one that can’t be answered definitively.

There are other reasons for his inability to break 4:00. Perhaps the main one is that his collegiate duties wore him down during the spring and took the edge off his summer performances. This happened in 1953 and 1954, but not in 1955. However, in 1955 his season was cut short by his military duties.

The next reason is the lack of competition. He was so much better that his American opponents that he was never pushed in fast Mile races. The lack of quality milers also meant he wasn’t paced like Bannister was by Chataway to the last 220-330 yards. Only twice, by Dalzell and by Barthel, was Santee paced properly for a 4:00 Mile.

|

|

The three great Milers from Kansas: Jim Ryun, Wes Santee and Glenn Cunningham. |

Finally there is his long battle with various track authorities. This must have distracted him somewhat, especially in 1955 and 1956. Further, his final ban in 1956 came just before the outdoor season got under way. A fast 800 in May (1:49.5, which he was able to run in military competition, suggested he was in good shape while still in the military.

So the college system, the lack of home-based talent, and his bitter battles with the AAU all contributed to his never running a Mile under 4:00. Soon after he was forced to retire, Don Bowden became the first American under 4:00 with 3:58.7. Santee maintained his connections with KU and fellow runners throughout his life. He also maintained connections with the military on a volunteer basis. Later in his life he worked with KU friends to reinvigorate the Kansas Relays and enjoyed many reunions. Running was in his blood to the very end.

6 Comments