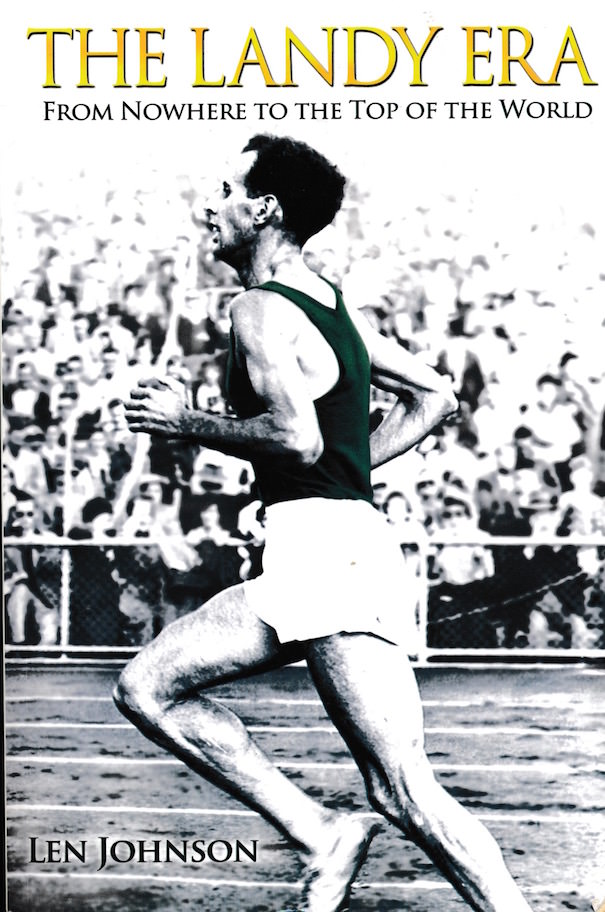

The Landy Era by Len Johnson: Book Review

|

There have been several books on Bannister’s breaking of the four-minute Mile, but until now we haven’t had a book that focuses on John Landy. This is not to say that there hasn’t been some good material on the great Australian miler. Neal Bascomb’s excellent The Perfect Mile provides some excellent material on Landy’s build-up to 1954; Nelson and Quercetani cover Landy’s career with their usual thoroughness in their indispensible The Milers. There is also good material on Landy, although on a smaller scale, in John Bryant’s 3:59.4: The Quest to Break the Four-Minute Mile and in Jim Denison’s Bannister and Beyond. But was not until Len Johnson’s The Landy Era, published in 2009, that have we been given the full story.

But as the title indicates, Johnson’s book is not a straight biography. Rather, Landy is the centerpiece of a study of the emergence of Australian distance running in the 1950’s, Johnson’s thesis being that Landy himself was crucial to this emergence. After a Foreword by Ron Clarke, Johnson immediately asks, “What role do tradition and culture play in creating sporting success?” This leads him to compare the original three main contenders for the 4-min Mile and conclude, “If culture and tradition do play a part in sporting performance, Landy represented a stark contrast to the other two. Bannister and Santee each had a tradition to draw on; Landy, and his generation of Australian runners, had to establish their own.” This sets up the focus of his book: How Landy in the main and others to a lesser extent put Australia at the top of the world in distance running during the late 1950s. It’s a story of creating something big out of very little: “…there was precious little to inspire young Landy from Australian history.”

In the first Olympics back in 1896, Australia began well when Edwin Flack won both the 800 and 1,500. But in the next 50 years, according to Johnson, “virtually nothing happened.” The best that Australia did was to have one middle-distance finalist in each of the 1928, 1932 and 1936 Olympics--hardly the basis for an emerging middle-distance culture. However, what was promising was “a flourishing club system” after World War 1: “Clubs, regular competition and healthy participation rates all formed a basis for further success. But until John Landy and his contemporaries came along, it was a case of all lunching pad, no rocket.”

Johnson’s superbly written book is about the Landy “rocket” that led to the veritable firework display that followed him: Albie Thomas, Merv Lincoln, Dave Power, Dave Stephens, Allan Lawrence, and last but certainly not least Herb Elliott. Also part of the story is a booster rocket to Landy’s rocket: the top clubs—St. Stephen’s Harriers, Malvern Harriers, Melbourne Harriers, Glenhuntly, Preston and Geelong Guild Club. As well, Johnson points to the national spirit after World War 2: Australia emerged from the conflict with a new spirit of independence and confidence. This spirit spread into the sporting scene.

According to Johnson, there was one more factor in the emergence of Australian running: the controversial Percy Cerutty. Of course Landy was advised by him him early in his career, and he has paid tribute to the coach’s groundbreaking promotion of hard training: “You have to see Cerutty in the context of the time when coaches were greatly concerned about over-training, about becoming stale, muscle-bound or even burnt out by doing too much.”

By page 48 the biography of Landy gets going with his 1948 Mile victory in the Associated Public Schools Combined Sports. At the same time we are also introduced to other important Aussie runners at the start of the 1950s: Les Perry, Al Lawrence, Albie Thomas and John Plummer.

Having set up his focus on Landy as the main force of the Aussie emergence, Johnson proceeds chronologically from the 1950 Commonwealth Games. We follow Landy’s early battles with Don MacMillan, which “revealed his competitiveness, a trait sometimes overlooked later in his career.” And we experience his first Olympics in Helsinki, where Landy learnt some valuable lessons that were to lead some rapid improvement in his Mile time: “We had a hell of a lot to do in training, but also in competition…. We had to do something to improve.”

Landy’s big breakthrough in December 1952 is covered in welcome detail with well-researched material from contemporary media coverage. Johnson can also be succinct when needed: “John Landy, who had never broken 4:10 before, had run 4:02.1.” Following this, Johnson takes up the race for the first sub-4 between Landy, Bannister and Santee. He effectively outlines the issues that each of the trio had to deal with. And he covers all six of Landy’s 4:02 Miles, showing the pressure he was under.

The story continues with Bannister’s 3:59.4, Landy’s 3:57.9, the epic Vancouver duel and finally Landy’s valiant attempt to get in shape for the Melbourne 1,500. In a brilliant last chapter, “The Legacy,” Johnson summarizes Landy’s contribution to Australian running.

By the end of the book, Landy’s personality, which is far from that of the conventional sports hero, comes shining through: his humility, his no-excuses attitude and his willingness to help others.

On a personal note, I was able to speak to Landy in 1994 at the Victoria Commonwealth Games, and I was surprised at finding myself thanking him for all he had done for the sport. I didn’t realise at that time just how much he had done. Now that I’ve read The Landy Era, I’m really pleased that I thanked him face to face.

Leave a Comment