Bob Phillips Articles / Profile

Going Great Guns: the Afro-American Pace-setter at the Olympic Games of 1924

By Bob Phillips

8th September 2018

Going Great Guns: the Afro-American Pace-setter at the Olympic Games of 1924

|

Frank Shorter’s 1972 Olympic marathon win rightly takes much credit for sparking off the distance-running boom in the USA, but maybe some consideration should also be given to the World record-breaker in that event in 1963, “Buddy” Edelen, The drawback regarding Edelen is that he had to go first to Finland and then to England to find the competition which transformed him from being a worthy but not exceptional college two-miler, and his exploits largely went unnoticed in the country of his birth.

Yet there were fine American distance-runners in a much earlier generation, and it’s a surprising fact that for a decade the USA actually performed better than Great Britain in such events at Olympic level. At the Games of 1920, 1924 and 1928 the USA took 25 places in the first eight at either 5000 metres, 10,000 metres, the marathon, the 3000 metres steeplechase or the 3000 metres team race to Great Britain’s 22. Some, if not most, of these achievers are long since forgotten, such as Horace Brown. Do you immediately recall to mind that he was the individual winner of the 3000 metres team race of 1920 – admittedly in the odd absence of any Finnish opposition?

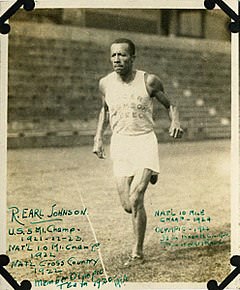

One of the medal-winning American distance men of that era who definitely deserves remembering is the cross-country bronze-medallist of 1924, Earl Johnson, about whom there is some confusion because various reference sources give his first names as “Robert Earl”, “Richard Earl” or “Earle”. Whether “Earl” or “Earle” is largely an academic matter, and the much more significant fact is that of his ethnic origin. He was not the first Afro-American with exceptional powers of stamina because there had been several over the years since a professional runner, Frank Hart, had won a six-day event at Madison Square Garden in 1880. Nor was Johnson the first Afro-American Olympic medallist in any running event because George Poage had earned bronze at the 1904 Olympics in both the 200 metres hurdles and 400 metres hurdles. But there has been no Afro-American Olympic medallist in distance events before or since – even Kenyan-born Bernard Lagat’s numerous medals do not include any for the Olympic 5000 metres. The 2016 silver-medalist at 5000 metres for the USA, Paul Chelimo, was also, of course, of Kenyan birth.

On the website dedicated to the prolific Afro-American distance man, Ted Corbitt (1919-2007), who ran 223 marathons or ultra-marathons during his career, including the 1952 Olympic marathon, Earl Johnson is described as “the first great African American distance-runner”, and there’s every justification for that claim. He won six AAU national titles, at five miles on the track (the standard distance event in the USA until 1924), 10 miles on the road and at cross-country. He competed at every event from one mile upwards, and in 1923 won a 22-mile race in Detroit in 2:09 and the next year a 10 miles in 54:29. In his 1923 AAU five-mile victory he beat the US-based Finn, Willie Ritola, by six yards, and the next year Ritola was to win two gold medals and two silvers at the Olympic Games.

Johnson intended taking part in the 1924 Boston Marathon, which was the qualifying race for US Olympic selection that year, but he was prevented from doing so by illness. Though he did not enter the 10,000 metres Olympic trial he was enterprisingly selected, anyway, for the cross-country event. His 3rd place there was never a challenge to the all-dominant Finns, Paavo Nurmi and Ritola, but he was one place ahead of Britain’s greatest distance-runner of the years between the two World Wars, Ernie Harper. It was an achievement in itself even to complete the course in the heat-wave conditions in Paris– only 15 of the 38 starters did so. Six days earlier Johnson had placed 8th in the track 10,000 metres in 32:17.0, and he and his team-mate, John Gray, were the only non-Europeans among the 16 finalists. Ritola won in a World-record 30:23.2.

Johnson had been born in Woodstock, Virginia, on 10 March 1891 and at some time early in his life became part of the great migration north by Afro-Americans. Like so many others, he went to Baltimore, Maryland, and then to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which was the booming centre of the American steel industry and increased its population from 49,000 in 1860 to 610,000 by 1930. He found employment as a community and welfare officer with the Edgar Thomson Steel Works company, which had been founded by the Scottish-born industrial magnate, Andrew Carnegie, in 1872 – and still survives as a major part of US Steel almost 150 years later.

Carnegie was a benefactor who provided recreational facilities for his workers, with organised teams for baseball, basketball and track & field. Johnson’s first major competitive appearance at the US Olympic Trials of 1920 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was made as a member of the Edgar Thomson club and he ran the German-born Frederick Faller close at 10,000 metres, 32:15.0 to 32:18.0, but at the Antwerp Games Johnson was 8th in his heat and therefore a non-qualifier and Faller a commendable 8th in the final, less than a minute behind the illustrious winner, Nurmi.

Johnson, slightly-built at 5ft 6½in (1.70m) in height, was clearly of an entrepreneurial spirit because he took charge of the Edgar Thomson baseball team which played in local “sand lot” matches long before any Afro-American was accepted by the major league professional teams. The “Pittsburgh Courier” newspaper was to say that “the lads under the tutelage of Earl Johnson have been going great guns for the past two seasons”, and one of the “lads”, Harold Tinker, who also competed for the track & field team, remembered that Johnson was “a very progressive guy and he went out and looked for ball-players”. Though originally set up solely for the employees’ benefit, the Edgar Thomson baseball team had a strong local following, and Johnson actively sought recruits from elsewhere. When the company reduced its financial support in the 1930s, Johnson kept the club in existence by organising various entertainments to raise funds.

He was also a sports feature writer for the “Pittsburgh Courier”, which was to become the leading Afro-American publication of its kind, with an influence and circulation extending far beyond the city limits to all 48 states and abroad. At its peak in 1947, when Johnson was still employed there, it was selling 357,000 copies per issue.

Johnson also developed a career as a coach, and one of the runners in his care, Rufus Tankins (1897-1969), was said to be “a veteran of 50 marathons”, though the term “marathon” in those days in the USA was used to describe almost any road race of eight miles or more in length. Another Afro-American runner, Augustus (“Gus”) Moore, of Brooklyn Harriers, emulated Johnson by winning the AAU cross-country title in 1928 and again in 1929 and has been reported as beating Paavo Nurmi in a two-miles race in 1930 with a time of 9:05! As the first sub-nine-minute World record was not set until the following year by Nurmi, it would be interesting to discover more about Moore!

It would be in excess of a quarter-of-a-century later that an Afro-American would set a national record in a distance track event. He was a US Navy serviceman, Joe Tyler, with 30:31.9 for 10,000 metres in Los Angeles on 7 June 1956. Tyler, who had also placed 8th in the Boston Marathon that year, failed to qualify at the Olympic trials, but another Afro-American, Charles (“Deacon”) Jones, did so in the steeplechase in both 1956 and 1960, finishing 9th and 7th in the respective finals – thus on the latter occasion improving on Earl Johnson’s Olympic track achievement by one place.

Johnson died in November 1965 at the age of 74.

Leave a Comment