Jules Ladoumègue Profile

1906-1973

1.71 (5’7”) 59kg (130 lbs)

|

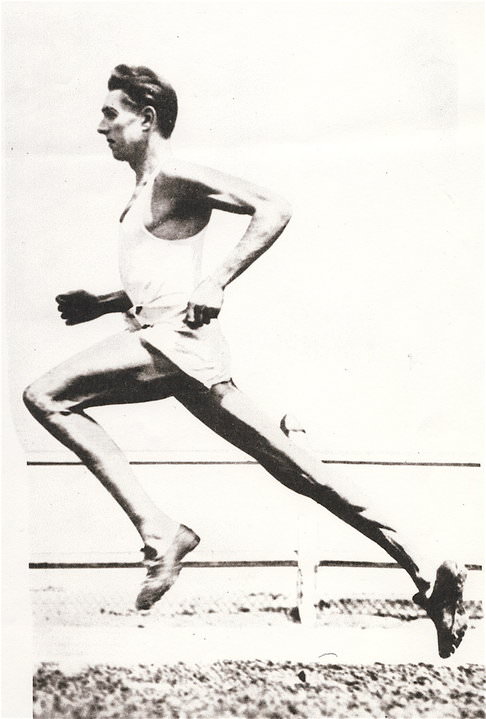

| The famous photo of Ladoumègue showing his fine running form. |

Not many runners can attract a 300,000 crowd to watch a ceremonial run in a city street. But on a gloomy and foggy November day in 1935, French runner Jules Ladoumègue did just that when he ran the length of the Champs Élysées to receive the homage of the French people. He had been banned from competition for nearly four years, yet the French people still remembered their beloved “Julot.” His popularity stemmed not only from his brilliant short career of six world records and an Olympic silver medal but also from his exquisite running style and his sensitive and endearing personality. For someone who had experienced several tragedies in his early life, the cheering of the massive crowd on that drab November day must have been all the more inspiring.

Early Days

Tragedy struck even before Ladoumègue was born. While his mother was pregnant, his father was killed in a dockyard accident. As if that wasn’t enough, his mother died in a house fire when he was just 17 days old. Fortunately an aunt and uncle came to the rescue and were soon his devoted parents. At 14 he quit his Bordeaux school and became an apprentice gardener. Soon after he was asked if he would like to run in a cross-country race that might qualify him for the area championships. The puny 14-year-old, after finding himself last in the early stages, won his first race. And then he won the South-West title too. Ladoumègue wrote that at this time it was difficult for people to take him seriously as a runner: “I ran rather like a kangaroo, using my legs more for making leaps than for making them run rhythmically.” (Dans ma foulée, p.23) There was no athletic program available, so his running came mainly from doing errands for his adoptive parents and his neighbours. He did take part in some local races that often earned him a few francs. In one of these races at a country fair, so the story goes, he gained an unusual victory. He was challenged close to the finish by a well-known local runner, Henri Dartigues. At the crucial moment of the race Ladoumègue’s dog Kiki, seeing his master being chased, darted out of the crowd and bit Dartigues’ calf. This enabled Ladoumègue to win.

Ladoumègue continued to work all day and train at night, often in the dark. From his workplace he often saw trotting racehorses out training: “I liked the striding of the horses, and I studied their leg movements…. One day as I ran along the railings, imitating naturally the stride of the trotting horses, a young colt left its mother to gambol beside me; we quickly became friends. It later became a great champion.” (DMF, p. 28)

|

The next step was for him to join a club—Union Athlétique Bourdelase. His debut was in his new club’s big race of the year-- the Bourdeaux-Saint-André-de-Cubzac, a 20K road race. After a slow start, he caught the three leaders 2K from the finish and went on to win. Ladoumègue quickly developed in club competition, and his new employer (he was now a decorator) supported him all the way. In 1925 the eighteen-year-old again entered the Bourdeaux-Saint-André-de-Cubzac 20K. This time he surprisingly dropped out at 15K while well in the lead: “I was experiencing no serious fatigue, but feeling depressed for no apparent reason, I suddenly had to stop.” (DMF, p. 1) Later, he claimed that the chaos before the race, caused by the passing Tour de France cycle race, had upset him. This was an early indication of how highly strung Ladoumègue was. “His sensitivity made him as fragile as crystal,” Robert Parienté wrote of his nervousness before a race. “If his handlers had given him free rein, he would have run from the stadium before going on to the track.” (La fabuleuse histoire de l’athlètisme, p. 328)

From Harrier to Track Runner

Ladoumègue quickly established himself as one of the leading runners in south-west France. At 18, however, he was still a harrier and knew little about track running . His interest in track had been stirred by a photo of the great Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi, which he bought and pasted up in his bedroom: “Nurmi became my model; I studied his career and was led to conclude that the 1,500 event was not a joke.” (DMF, p. 41) Soon Ladoumègue was approached by the Bordeaux club Stade Bordelais, and with the blessing of his old club, he joined with the aim of becoming a track runner. “Gone were the roads, the trees, the fields!” he wrote. (DMF, p. 42) But there was another ominous aspect to this transfer to a new club: Stade Bordelais paid 500 francs to French officials to get Ladoumègue reinstated as an amateur. (Bob Phillips, 3:59.4, p. 74.) Professionalism was to blight his running career just a few years later.

Ladoumègue was soon lining up for his first 1,500. Overwhelmed by the noise of the loudspeaker and the crowd, he flopped. But his club, aware of his talent, took steps to protect him from the hurly-burly of track meets. He also had to adapt his running action which had been formed by road running: “My ‘kangaroo’ style was primitive. My feet, accustomed to the road, needed to get used to grass surfaces; patience was needed. My weakness would be corrected and my qualities developed.” (DMF, p. 44)

Military Service

In his first big track meet, the 1926 French Championships, the 19-year-old finished third in the 5,000 and earned a place on the French team against Great Britain. In this international race he was again third, improving his PB to 15:11.6, which ranked him 19th in the world that year. His running career changed direction as soon as he got home: he had to enlist for military service. Although he was able to continue running, the new military life adversely affected his form. He was only eighth in the French cross-country championships. And he was disappointed with his 22nd place in the Five Nations cross-country race in Wales. Still at 20, he was already a track and a cross-country international.

|

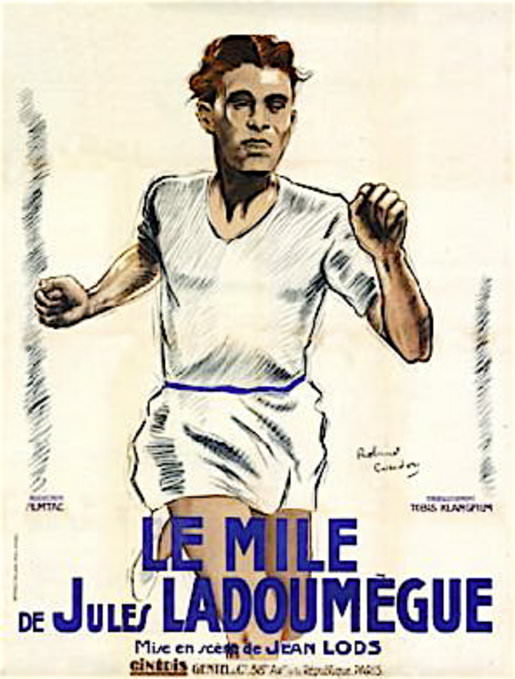

| Poster for the 1932 film. |

The 1927 track season started well for Ladoumègue, but the early promise was not fulfilled that year. First he defeated the number-one French 1,500 runner, Sourdin, with a 4:04 victory on a grass track. He raced over 1,500 at least five times in the summer, but he was unable to break the 4:00 barrier, his best time being 4:01.6. However, he did break two French records at the end of the season. Running solo he knocked 4.8 seconds of the French 2,000 record with 5:30.0. Fired by this breakthrough, he then successfully attacked Guillemot’s 3,000 record of 8:42.2 and ran 8:40.0.

For the last part of his military service Ladoumègue was transferred to Paris. While this was a big wrench from family and friends, it did take him to the centre of the sport, where he joined up with Charles Poulenard, one of the top French coaches. This was fortunate because Ladoumègue was still concerned about his running style: “To correct my bouncing running style, I chose an avenue in the Vincennes Forest where the overhead branches formed a roof. To run along this avenue I had to lower my head. Every morning I made myself run as fast as possible in such a manner. This had the effect of diminishing my worst flaw.” (48) He also worked hard in the gym for strength and flexibility.

Breakthrough

As the 1928 Olympics approached, Ladoumègue was demobilized. Deciding to stay in Paris, he changed clubs again, joining Stade Français. He now had to choose between the 1,500 and the 5,000. After winning the 1,500 in a major four-country international with 3:55.2, and aware of Poulenard’s concern over his strength for 5,000, Ladoumègue opted for the 1,500. It was a good decision for he soon won the French 1,500 title, equaling the French record of 3:54.6. A few days later he ran the fastest 1,500 of the year with 3:52.2. All of a sudden, he was an Olympic favorite.

Amsterdam Olympics

Ladoumègue’s fragile personality was severely tested during the Amsterdam Olympics. He was soon at odds with the French camp’s “narrow-minded administration, its pettiness, its utter coldness and its hierarchical rigidity.” (DMF, p. 53) It didn’t help that one his Stade Français closest team-mates, world-record-holder Séra Martin, finished only sixth in the 800.

Ladoumègue qualified for the final but received no support from French officials. In the final, he started cautiously, before moving slowly through the field. By 800 (2:04) he was in sixth position behind the three Germans, Ellis and Purje. Then the Finns Larva and Purje took over the lead. As Ladoumègue tried to move up at the bell, he had trouble passing the three Germans, who were running side by side. By the time he had managed to get by, he found Purje 15 meters ahead. Chasing Purje and trying not to panic, he passed Larva, who perhaps knew his Finnish team-mate had gone too soon, and closed the gap gradually. He was on Purje’s shoulder with just over 200 to go: “Running elbow to elbow, we exchanged pained expressions. One of us had to give in. I was at the end of my tether, no longer knowing if I was running to win. In my semi-consciousness, I realized that Purje was no longer with me.” (DMF, p. 55)

Ladoumègue, at one point, had a five-meter lead, but as Purje dropped back, his team-mate Larva passed him and seeing that Ladoumègue was slowing, went after the leader. He passed Ladoumègue 20 meters from the tape. Larva’s time was 3:53.2, Ladoumègue’s 3:53.8. Purje was three seconds behind in third. Ladoumègue blamed the effort to pass the three Germans and the struggle with Purje for exhausting him before the tape. Parienté has written that the 21-year-old Ladoumègue showed his inexperience by going too soon. It can be argued that the highly strung Ladoumègue made the same mistake as Jazy made 36 years later, not being confident enough to hold back and making his final effort too early. But surely Ladoumègue had to react to Purje’s burst if he was running to win. In the final analysis, as Bob Phillips has written, the inexperienced Ladoumègue “did very well in the circumstances.” (DMF, p. 74)

After the Olympics Ladoumègue showed his great form with six consecutive victories over 1,500; two of them were in the fast times of 3:52.3 and 3:52.8. He finished off his season with an impressive 800 in 1:52.0, which was only 1.4 seconds outside Séra Martin’s WR. He had wanted a return race with Larva, but it wasn’t to be. Overall, his 1928 season, though disappointing from the perspective of missing an Olympic gold medal, showed that he had become one of the very best 1,500 runners in the world. He had improved his time from 4:01.6 to 3:52.2. Peltzer’s world record of 3:51.0 was clearly within reach.

Setback

During the winter, Ladoumègue changed clubs yet again, partly to avoid a feud between Paris clubs and partly to live again with his adoptive parents. In joining the CASG club, he managed to get an agreement whereby he could live with his parents in an abandoned pavilion at the Jean Bouin Stadium in Paris. His father and he also negotiated employment with the rich CASG club. It was a cosy arrangement that bordered on professionalism.

|

Despite malicious gossip about his change of clubs, Ladoumègue settled down to his winter’s training. But he claimed that he made a big mistake that winter: “1929 was the worst year of my career. I made a big mistake in abandoning cross-country in the winter. Badly advised, I thought I was a sprinter at this time and I trained with sprinters…. I wanted to imitate the sprinting of Peltzer and Lowe. I was wrong. My muscles were strained by training against their nature.” (DMF, p. 62).

When he started competition, the Olympic silver medalist could barely break 4:00 for 1,500. So he dropped down to the 800 and won this event in the French Championships. Although he managed to win most of his 1929 races, his best 1,500 time was only 3:55.4. Even his speed let him down in a match against Great Britain. Still believing he had developed a potent finishing kick, he purposely went slowly and waited for his old rival Cyril Ellis to attack. When Ellis did attack near the end of the race, Ladoumègue was unable to respond and lost 4:04.0 to 4:04.2. A week later in Berlin he finally got his rematch with Olympic champion Larva. But again he was outkicked, losing a close race 3:56.6 to 3:56.8. Not surprisingly Ladoumègue does not mention this loss to Larva in his autobiography. Still, there was some encouragement at the end of the season: two 1,500 victories in international matches against Germany and Finland (3;55.4, 3:56.2).

Training Solution

In the 1929-1930 winter, fully convinced that his previous winter’s sprint training was wrong, Ladoumègue went back to distance training with the “crossmen,” as he called them. He soon began to feel like his old self: “My stride, free of the excesses I had imposed on it, rediscovered its former flexibility, and my muscles improved during the long runs that I carried out on grass.” (DMF, p. 64) He was also happy to be back living with his parents in their home right by the Jean Bouin track: “While my mother made coffee, I used to go across to the track in my pajamas, often barefooted, to dream about track running.” (I, p. 65) For someone so highly strung, it was very important for him to be at ease with himself and his sport. So his set-up at the Jean Bouin stadium worked wonders for him: “Slowly I discovered a new and harmonious attitude which allowed me to run with total serenity.” (DMF, p. 66)

The Record Spree Begins

Throughout 1930 Ladoumègue was unbeaten. Indeed, 1930 proved to be his greatest year, for it climaxed with world records for 1,500 and 2,000. After an early 800 win in an encouraging 1:53.2, Ladoumègue won his first 1,500 of the season, beating Italian star Beccali by 3.4 seconds. His time was faster than he had run the previous year: 3:53.8. Three weeks later he faced British runner Ellis, who had beaten him in 1929 with a sprint finish. This time Ladoumègue was quite a different runner. After 600 and despite the strong wind, Ladoumègue took the lead with Ellis on his shoulder. According to the Times correspondent, “he never looked like being headed.” Ladoumègue’s prolonged finishing kick earned him a 15-meter lead by the finish and high praise from the Times: “He is surely as glorious a miler as anyone could wish to see, with a superbly long and easy stride.” (Times, August 3, 1930) Ladoumègue’s time of 4:15.2 was a French record. His ease of victory in gusty conditions suggested that faster times were to come. And come they did in the autumn of 1930. Ladoumègue wrote how much he liked running in the fall: “I especially like practicing my sport in this season. The fresher air stimulates a prolonged effort. In the evenings, wrapped in a track suit with a cap on my head, I would be overwhelmed with dreams.” (DMF, p. 68)

|

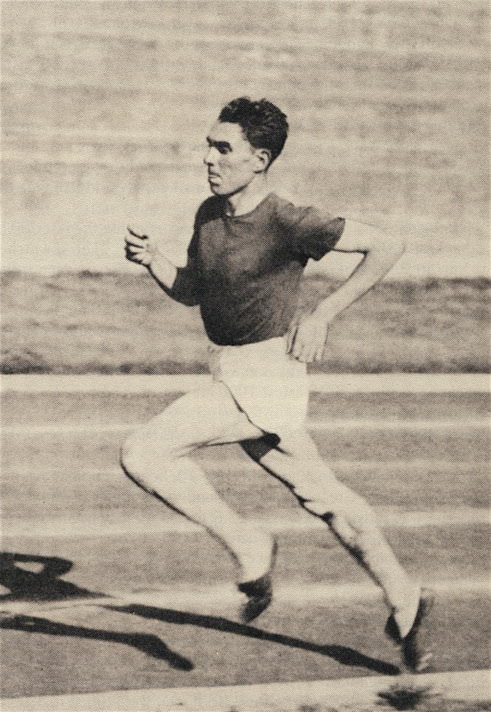

| 1,500 world record: just before the bell. Ladoumègueleads Beccali. Pacemaker Martin has just dropped out;he can be seen behind Ladoumègue. |

Ladoumègue was clearly in the form of his life. He had three more 1,500 impressive wins in August and September, including one against the current holder of the 1,500 WR, German Otto Peltzer. This victory gave him more encouragement to attack Peltzer’s 3:51.0 record. One day he went out into the Bois de Boulogne and writing with a twig on a clear patch of earth, he calculated what he needed to do on the 500m Jean Bouin track: 500s of 1:16, 1:17 and 1:17. That would get him a time of 3:50, two seconds faster than he had ever run and one second under the world record. For the attempt on October 5, Beccali, the fine Italian runner, was invited. It was to be a paced attack on the record, with his CASG team-mates doing the early work. The race day was rainy and there was a light wind. In the morning of the race, Ladoumègue watched his mother walk out to the Jean Bouin track and pour water from a bottle onto its surface. He later found out that the water was from the holy shrine at Lourdes. (Marcel Hansenne interview with L, quoted in The Milers, p. 60)

|

| The rugby players in his club celebrateLadoumègue's 1,500 world record. |

The race started well as his teammate Keller took him through 400 in 58.6 and 500 in 1:13.4. As Keller passed 800 (2:00.4), Ladoumègue shouted at him to go faster. But Keller was spent and 100m later he dropped out, leaving Séra Martin in the lead. They passed 1,000 in 2:33.Martin was only able to hold on for another 80m. At this point, when Martin moved aside, Beccali was still just in contact. Ladoumègue later admitted that at this stage of he race he was worried about the Italian’s finishing kick. Thus once in the lead, he pushed hard, although there was still more than a lap to go. He passed 1200 in 3:05, one second faster than Peltzer’s time during his 3:51.0 WR, and managed to maintain his pace, running the last 400 in 60.4 and the last 300 in 44.6 for a time of 3:49.2. He had broken the WR by 1.8 seconds. He was the first man every to run under 3:50.

The next day he went back to his forest and wrote new figures in the earth: 1:11 + 1:12 = 2:23. He was now thinking of the 1,000 WR. And two weeks later, again helped by Séra Martin, he did run a 1,000 WR with 2:23.6. This eclipsed the old mark of 2:25.8 that was also set by Otto Pelzer. Unlike his 1,500 record, which lasted only three years, this 1,000 record was to stand for eleven years until Rudolf Harbig ran 2:21.5. After this second WR, Ladoumègue said that he had waited too long for his final effort and felt he had more left at the tape.

At the Top of the Game

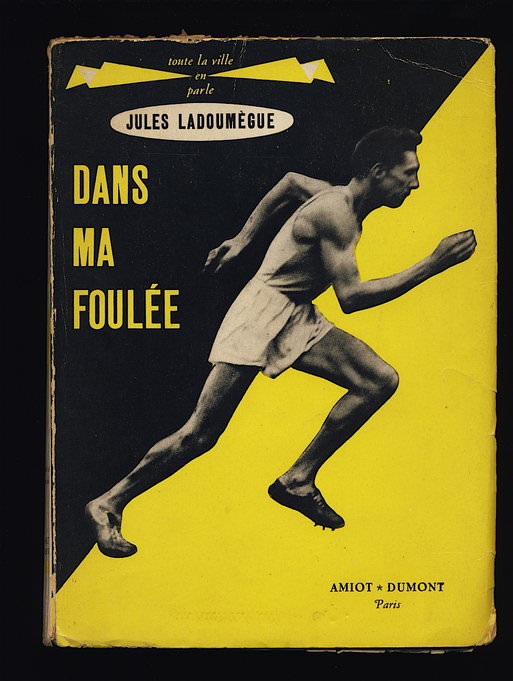

|

| Winning at the Stade Jean-Bouin in 1930. |

His life changed dramatically the following winter. First his adoptive father died; second, he got married. He was still working with Poulenard, who urged him to attack Purje’s 2,000 WR of 5:23.4, which had been set in 1927. In July, at the Jean Bouin Stadium, he made his attempt. Passing 1,000 in 2:38 and 1,500 in 4:02, he finished 1.6 seconds faster than Purje’s mark with a new WR of 5:21.8. Then, after a 1,500 victory in Stockholm, he attacked an obscure record for 2,000 yards. He ran 4:52, which he claimed as another WR.

Next Ladoumègue won two 1,500s. The first was in Stockholm (3:54.4) Then in the annual match against Great Britain he again faced his old rival Reginald Thomas, who was improving each year and had become his country’s number one. After breaking away from Thomas with 300 to go, Ladoumègue had a 1.4 second margin at the tape, finishing in 3:53.6.

Yet another world record was to come. This was achieved on September 13 at Colombes Stadium over the unusual distance of 3/4 Mile. Purje came from Finland for this race. And his surprising break late in the race helped Ladoumègue to run a fast time. He was jumped by Purje with 300 to go and was left 10m back. Gradually he pulled the Finn back and just managed to catch him at the tape, both runners recording the same time. His effort in catching Purje earned him a time of 3:00.6, which was 2.2 seconds inside the world record.

Attack on the Mile World Record

|

Now with five WRs, three of them at established distances, Ladoumègue set his eyes on the eight-year-old Mile world record of 4:10.2 that belonged to his hero Nurmi. Again he decided to make the record attempt in October and again he chose the 500-meter Jean-Bouin track. He asked Purje to run, but the Finn refused to take part in an attack on his fellow countryman’s record. Had he run, he might well have pushed Ladoumègue to an even faster time. In the perfect fall weather, the seven runners had three false starts—one by Ladoumègue-- before the race got under way. Ladoumègue has described what was going on in his mind as the race started: “Everything was a blur. Only the image of Nurmi was clear. I could hear his voice. It rose above the roar of the 10,000 spectators. It seemed as though Nurmi was encouraging me: ‘Ladoumègue, Ladoumègue.’” (DMF, p. 87)

René Morel, a 19-year-old 800 specialist, took the field through 800 at a perfect speed: 60.8 and 2:04.2. After reaching 1,000 in 2:34.6 he began to slow, and Ladoumègue had to take the lead. He was on his own at the bell (3:08 and 1.3 seconds behind Nurmi’s WR pace). ‘This was when my really race began,” he wrote later. “I felt fresher than ever before. I went with 450 to go, thinking only about making up the time deficit [on Nurmi’s pace]. I lengthened my stride, breathed deeply and lifted my head slightly. I was amazed how quickly the finish line appeared. When they called 3:52.4 at 1,500, I knew I was going to outdo Nurmi.” (www.volodalen.com/32historique/ladoumegue.htm) In the last 300 he had moved ahead of Nurmi’s pace, and he was still able to finish strongly. He broke the world record by 1.2 seconds with 4:09.2 to become the first man under 4:10.

Professionalism Ban

With all the world records from 1,000 to 2,000 Ladoumègue had done it all—except win an Olympic gold medal. And judging by his 1931 form he looked almost certain to achieve that at Los Angeles in 1932. But that was not to be. The charge of professionalism, which was always hovering over the amateur sport of athletics in those days, was about to descend on Ladoumègue. Charges came from Sweden and Germany. And since both countries had a runner in the top ten rankings for the 1,500, their motives were suspect. Nevertheless, the French administrators, who also had to deal with allegations against Ladoumègue in France, had to decide whether to ban their country’s best hope of an Olympic track gold medal.

Over the winter the debate was fierce. There had been allegations before, but this time there was a full inquiry. Finally on March 4, 1932, the 25-year-old Ladoumègue was banned for life. Devastated by the ban, he said that the authorities had cut off his legs. Later he wrote that the decision was the same as cutting off the hands of a pianist. Whipped up by a sympathetic press, an uproar spread across France. During 1,500 races that summer in France, the crowd would chant “Ladoumègue, Ladoumègue” even though he was not in the race. Jack Lovelock experienced this chanting in 1933 when he made an attempt in Paris to break Ladoumègue’s 1,500 WR. Ladoumègue did finally attend the 1932 Olympics, but only as a spectator. A well-heeled supporter paid for his travel to Los Angeles. Nurmi was there as a spectator too, also banned for professionalism. “You should have remained a gardener,’ L was told by his mother. “You would have suffered less.” (DMF, p. 114)

Professional Runner

Ladoumègue continued to run, but as a professional. While in the US he had turned down $10,000 a month for a six-month contract to tour the American continent. When he returned home, he found that he was banned from training on all but one of the French running tracks, even from his beloved Jean Bouin track that he could see from his apartment window. (Late in 1933 he was allowed back to this track for a short period and then was banned again.) Ladoumègue ran a lot of races in 1933, gradually improving until his times were close to his records. In fact he beat his 3/4 Mile record with 2:59.2. He also ran two very fast 1,500s in 3:50.8 and 3:50.6. In 1934 he was invited to run in Moscow against the Soviet star Denisov. He won all his three races, two of them against Denisov.

|

In 1935, Ladoumègue ran what he called “the most beautiful race of my life.” (DMF, p. 173) The newspaper Paris-Soir arranged for him to make a ceremonial run down the CE. “The citizens of Paris were invited to come and demonstrate against the bias of the [athletic] Federation and to show sympathy for my situation,” he wrote. (173) According to Ladoumègue there were 300,000 people lining the famous avenue; later reports all say there were 400,000. Ladoumègue himself found it a frightening experience as people swarmed around him and wanted to touch him.

Two years later he joined a touring circus for a while, billed as the man with a 2.25m stride. He turned down offers to run professionally in England, Australia and Brazil. His circus career was halted when he was called up for military service in September 1938. Bizarrely, in the middle of World War 2 in 1943, his athletic ban was lifted. After the war he worked as a radio sport commentator. His book Dans ma foulée was published in 1955. He lived long enough to witness the exploits of the next great French runner, Michel Jazy. Stomach cancer took his life in 1973 at the age of 66.

Retrospect

|

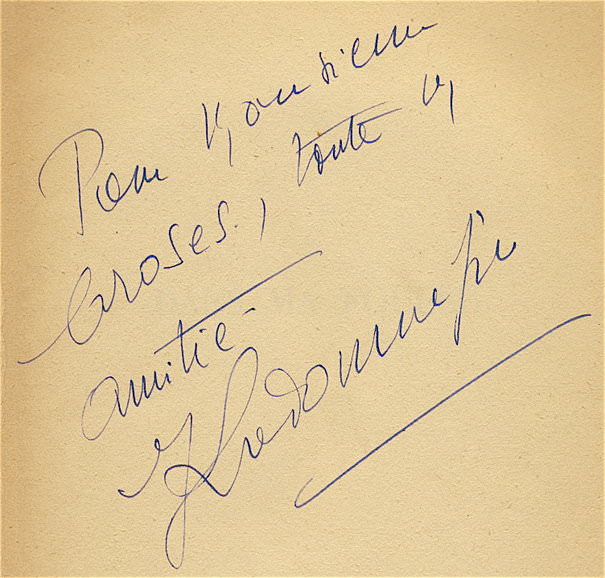

In his short career—he had only four years at the top—Ladoumègue was rarely beaten. Although primarily regarded as a record-breaker, he was a fierce competitor who was always in contention to the end. His Olympic silver medal was certainly a fine performance for a 21-year-old who had only just reached world class. (Compare his Olympic performance to Roger Bannister’s in 1952: Bannister was 23 and finished fourth.) Nevertheless, Ladoumègue will be remembered mainly for being the first to break the 3:50 and 4:10 barriers for the 1,500 and Mile. His strength was his ability to maintain a fast speed for an extended period; both his 1,500 and Mile WRs were achieved through a prolonged effort that began before the final lap.

And then there was that beautiful running style that elicited many poetic descriptions from journalists. Of course, he had a lot of natural ability, but he worked hard to develop a long and efficient stride out of his youthful “kangaroo” gait. Although some fine photos of him are available, sadly the 39-minute film made about him in 1932, Le mile de Jules Ladoumègue, is hard to find. However, there are three good film clips of him on ina.fr in the “Sport” section under his name. He can be seen running a demonstration on the track, running down the Champs Élysées in 1935, and running through the forest in 1963, when he was still in incredible shape. Was there ever a more elegant runner?

Note: All DMF quotations are from Ladoumègue's autobiography Dans ma foulée. The translations from the French are mine.

2 Comments