Arne Andersson v Gunder Hägg (1944)1,500 Gothenburg, Sweden, July 7, 1944Great Races #4 In his first race of 1944, Gunder Hagg had been humiliated by Arne Andersson in a 1,500 race. Andersson had stayed with Hagg throughout and then roared by in the last 120 to open up a nine-meter lead. Hagg’s defeat had been so decisive that rumours spread that the great man had thrown the race.Clearly Gunder Hagg had to recapture his reputation as the world’s greatest runner. His plan was simple. In view of the devastating finishing kick that Andersson had demonstrated, a kick that seemed to be more potent than ever, Hagg would literally have to run his opponent off his feet with a blistering pace. To help with this plan, Hagg enlisted the help of 23-year-old Lennart Strand, who was to win a gold medal in the 1946 European Championships and a silver in the 1948 OG—both in the 1,500.

Gunder Hagg v. Arne AnderssonOne MileMalmo, Sweden, July 18, 1944A capacity crowd paid to see yet another great race between Arne Andersson and Gunder Hagg. The two Swedish runners had been rivals since 1942 and had had many exciting duels, often setting WRs in the process. Hagg had beaten Andersson every time in 1942, but this year, Andersson appeared to be Hagg’s equal. Not only had he beaten Hagg’s WRs for 1,500 and the Mile in 1943, but he had also beaten Hagg in their first 1944 encounter over 1,500. Then Hagg had won the second race. Clearly this third encounter of the season was going to be a classic.

Bannister v Landy1954 Empire Games Mile, Vancouver, CanadaGreat Races #9 The build-up to this race was incredible. Athletics, as one of the truly international sports, had followers all over the world. The first four-minute mile had captured the imagination of millions. And now the first two runners to have broken that barrier earlier in the summer, Roger Bannister and John Landy, were to meet in the Vancouver Empire Games. The race received huge coverage in the world press. It was given an array of names, The Miracle Mile, The Mile of the Century. As well, the television cameras were ready to supply the new medium live to an estimated 10 million North American viewers. Radio provided live coverage to the rest of the world. Bannister and Landy had become celebrities, hunted down by reporters and cameramen as soon as they arrived in Vancouver. The two runners dealt with the situation in different ways: Bannister avoided attention as much as he could and trained in private; Landy was happy to talk to anyone and trained in public.

Bannister's 3:59.4 First Four-Minute Mile, Oxford, UK, May 1954Great Races #8 The black-and white photo of Roger Bannister crossing the finish line in Oxford on May 6, 1954, is one of the most famous in the history of running. Head back, eyes closed and mouth agape, with transfixed spectators and an overwhelmed official in the background, Bannister is caught a fraction of a second before he breasts the tape just less than four minutes after the starter’s gun had fired. This was the moment that man first broke four minutes for the Mile. It was a symmetrical barrier: four laps of a quarter-mile track to be run in less than one minute per lap. Several athletes had come close over the previous dozen years. Yet there was something about the symmetry of the four-minute mile that made is seem impossible. This impossibility had surely affected Hagg and Andersson in the 1940s. And the same psychological effect was felt by the leading milers in the 50s when John Landy, Wes Santee and Roger Bannister were all “racing” towards the first sub-4. The story of these three great runners’ attempts to be the first is finely recounted by Neal Bascomb in his book The Perfect Mile.

Bolotnikov v Tulloh v Zimny5,000 European Championships 1962Great Races #15 Following his convincing 10,000 win, Russian Pyotr Bolotnikov (See Profile) looked a good bet for this race too. But his heat for this final was held only 24 hours after his 10,000 final. Further, he was forced to run a fast 13:53.4 to qualify (10th fastest time in the 1962 world rankings), so the recovery powers of this 32-year-old Russian were sure to be tested. The two other heats were won in the slow times of 14:14 and 14:15. Janke, who had run so well in the 10,000 was still tired and could manage only 8th in his heat. Prominent among the qualifiers were Zimny and Boguszewicz of Poland and Frenchmen Bogey and Bernard. Englishman Tulloh thought he had a chance. He had run a four-minute Mile and an 8:33.4 Two Miles in January, which meant he had the best basic speed in the field, but he had recently been beaten by Zimny.

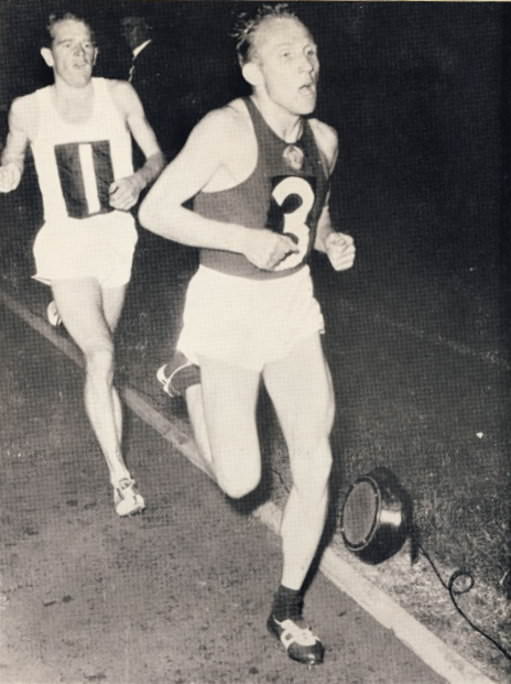

Chataway v Kuts 5,000: KUTS V. CHATAWAYLONDON, 13 OCTOBER 1954Great Races # 10 This famous 5,000 race took place during an international meet between London and Moscow at the White City Stadium in London. It was the first visit by a Russian team since 1878. These were the days before floodlights were developed, when movable spotlights, set up on the stadium roof, were used to highlight the runners in the gloomy evening. It was another classic front-runner-versus-kicker race. WR-holder Kuts (27) knew he had to run away from Chataway (23); Chataway knew he had to hold on to Kuts throughout and rely on his faster finish. Kuts had already shown that he was able to use pace variation to good effect; this, apart from a pure fast pace, is often the front-runner’s best weapon. And Chataway, of course, knew he would have to deal with this pace-variation tactic, having just been defeated by Kuts a few weeks before in the European Championships.

July 24, 1952, Helsinki, FinlandGreat Races #7 With six runners all thought to have a chance of winning, this Olympic final promised to be a dandy. Herbert Schade, 30, of Germany had the best time over this distance in the 1952 season. The already crowned 10,000 victor, Emil Zatopek, 30, admitted publicly that the German was the one to watch. After all, the German’s best 1952 time was ten seconds faster than Zatopek’s. But there were many who thought that the Czech’s amazing competitive spirit would win out. Then the man who beat him in the 1948 5,000, Gaston Reiff, 31, was also in the field: if he could do it once, he could do it again, though perhaps that would be unlikely as he had not been in top form. Then there was the brilliant Algerian-born Frenchman Alain Mimoun, 31. He now had two Olympic 10,000 silver medals to his name, both behind Zatopek. He was in good form and had to be able to beat the Czech one day. Finally, there were two young 21-year-old Englishmen, Christopher Chataway and Gordon Pirie. Both were improving fast and both were capable of a big breakthrough.

Clarke v Keino v Stewart v McCafferty v Rushmer5,000, Commonwealth Games, 1970Meadowbank Stadium, Edinburgh, Scotland Great Races # 22 Prospects This 5,000 race had all the qualities of a Great Race. It took place in a major games, it fielded some of the world’s finest middle-distance runners, it recorded four of eight all-time fastest clockings, it involved some intriguing tactics and it ended up with a very exciting last two laps. Roberto Quercetani considered that this race had “hottest finish in the history of the event.” (Track & Field News, July, 1970)

Elliott v Jazy v Rozsavolgyi1,500, Olympic Games 1960, RomeGreat Races # 13 This race had a clear favorite: Australian Herb Elliott. His stunning Mile and 1,500 WRs in 1958 had shocked the world. The only concern was his lack of top-class competition immediately before the Games. Still, there were some other good runners in the field. Dan Waern of Sweden and Rozsavolgyi of Hungary were the pick from Europe. And France had two promising finalists in Michel Bernard and Michel Jazy. Two other potential medalists, Merv Lincoln of Australia and Siegfried Valentin of East Germany, were eliminated in the heats.

Santry Mile, Dublin, August 6, 1958Great Races # 12 Using the prestige of Ron Delany’s Olympic 1500 gold medal in Melbourne, Billy Morton, a 48-year-old optician who was secretary of Clonliffe Harriers, organised the building of Santry Stadium in Dublin. The famous En Tout Cas company, which had built the Melbourne, Cardiff and White City tracks, was hired for the job. They used a base of 9 inches of ashes from the local Guinness factory and on top 3 inches of their own secret formula of clay, shale and sand. The track was hard and spikes came out of it cleanly.