1966 European Championships

Budapest, Hungary

August 30-September 4

800

There was a stellar field for the final of this event. Favorite was the new Euro record-holder Franz-Josef Kemper (1:44.9). Fellow West German Bodo Tummler, who had won the 1,500 three days earlier, was also fancied. The Great Britain also had two finalists: British record-holder Chris Carter and John Boulter. But the runner who received the most interest was the current Euro champion Manfred Matuschewski of East Germany. In 1962 he had shocked everyone with his phenomenal finishing kick. But in the Tokyo Olympics he was eliminated in the semifinals. Was he at 27 past his best?

|

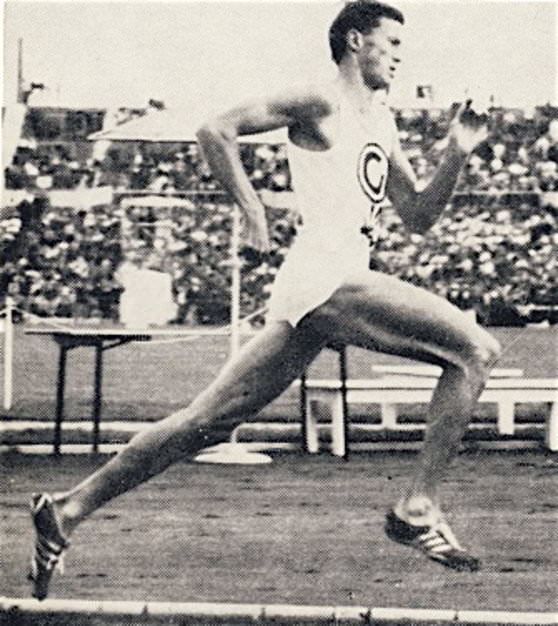

| 100m to go: Carter leads Tummler, Boulter and Kemper. Matushewski, the winner, can be seen behind Boulter. |

The field was led through the first lap by Chris Carter (25.4/51.7). At 600 (1:19.3) a determined Carter was still ahead, and he held his lead round the final bend. There were four runners almost side-by-side as the field entered the last 100. Carter was inside, then Tummler, then Boulter, and on the outside and almost in lane three was Kemper. The West German had run the first lap at the rear and much of the second lap in lane 2 or wider. Behind these four was Jungwirth in lane 1 and Matuschewski in lane 2.

Tummler, perfectly placed on Carter’s shoulder, moved into the lead--but not for long as Kemper’s charge continued. The favorite looked to have the race sewn up. However, Matuschewski saw a gap opening up as Boulter faded. He dug down and found he still had the kick that had served him so well four years earlier. At the tape, the East German had just 0.1 margin over Kemper. Tummler just held on for the bronze as Carter fought back in the last 50m. The plucky Brit was rewarded with another British record, but he would surely have preferred a medal.

This wonderful race produced a meet record, four national records and five PBs. Kemper was a second off his best, but because of his poor positioning, he must have run much farther than any of his competitors. Had he not given himself so much to do in lap 2, he would surely have been able to hold the lead to the tape. Full credit to Matuschewski for his brilliant finish, but he must be considered lucky to have found a gap so late in the race.

1. Manfed Matuschewski EG 1:45.9; 2. Franz-Josef Kemper WG 1:46.0; 3. Bodo Tummler WG 1:46.3; 4. Chris Carter GBR 1:46.3; 5. Tomas Jungwirth CZE 1:46.7; 6. John Boulter GBR 1:47.0.

1,500

This promised to be an absorbing race as there were three types of runners competing for honours. Both Norpoth and Jazy were 1,500/5,000 runners who combined endurance and speed. Jazy had posted two 3:36.3 clockings in June; Norpoth, on the other hand, had run only 3:40.8. Opposing them were three specialists at this distance (seasonal bests in parenthesis), Simpson (3:39.8), Odlozil (3:37.6) and May (3:38.0). Of the third type was an emerging German star who was an 800/1,500 specialist, Bodo Tummler (3:40.8). All of these five runners except a sick Odlozil made the final.

A deciding factor in the final was the wind. The wind always discourages leading and in a major championship leading in windy conditions would be close to self-sacrifice. Both Jazy and Norpoth needed a fast pace to exploit their endurance advantage. French finalists Wadoux and Nicholas might have sacrificed themselves for their countryman, but sacrificing oneself after making a Euro final was a lot to ask. Perhaps Jazy, who was in good form, believed he was fast enough to win a slow race. As it turned out it was the other 5,000/1,500 specialist Norpoth who felt he had to lead; unfortunately for him he was unable to make the pace fast enough.

|

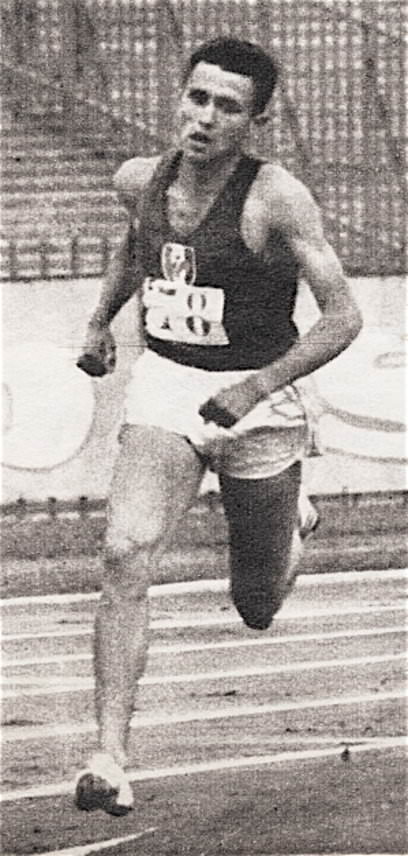

| The strength of Bodo Tummler 's stride. |

A large field of 12 was led through 400 at a reasonable 59.5 pace by Belgians De Hertoghe and Allonsius. The pace then slowed to the point that Norpoth felt he had to take over. But his time at 800 (2:03.4) was much to slow. Norpoth accelerated a little, passing 1,000 in 2:34.1 and 1200 in 3:02.5. By this time Jazy and Tummler had moved up to Norpoth, while Jurgen May dropped back.

At this point, with 300 to go, Norpoth made his bid for victory. Tummler and Jazy had to work hard to stay in contention. Norpoth led round the last curve from Tummler and Jazy, but finally weakened in the last 100, Tummler catching his with 50m to go. Jazy was in a good position to take Tummler , but all he could do was to get by Norpoth. Using his 800 speed, the victorious Tummler had run the last 300 in 38.8 and the last 400 in 52.7. Behind the tightly bunched first three, Alan Simpson passed May just before the tape for fourth. He had been badly boxed in; only in the last 50m was he able to get free.

Tummler must have felt that the field had given him the race. As the runner with the best speed, all he needed was a slow race. Jazy made no effort at all to enliven the early pace, and Norpoth, when he did lead, was not aggressive enough. So much for the 1,5000/5,000 specialists who needed to exploit their endurance. As for the three 1,500 specialists, perhaps an earlier drive for the tape would have worked. Surely Simpson and May must have felt comfortable with the 3:02.5 pace at 1,200. There was clearly a lack of assertiveness from the four who finished behind Tummler.

1. Bodo Tummler WG 3:41.9; 2. Michel Jazy FRA 3:42.4; 3. Harald Norpoth WG 3:42.4; 4. Alan Simpson GBR 3:43.8; 5. Jurgen May EG 3:44.1; 6. Andre De Hertoghe BEL 3:44.3.

5,000

|

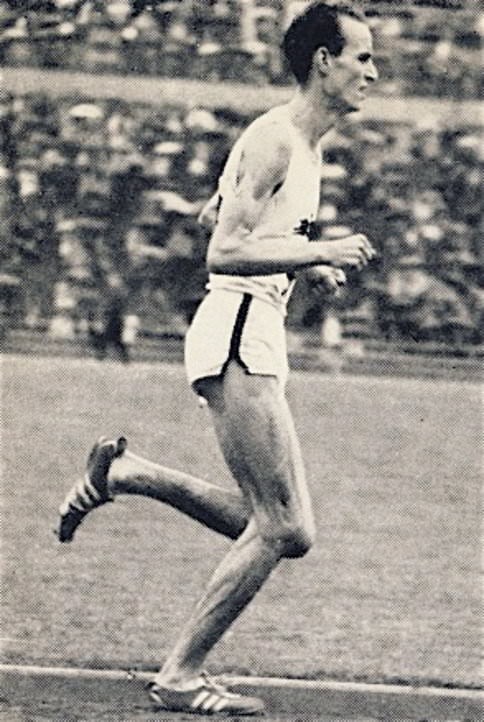

| Michel Jazy. |

All eyes were on Michel Jazy of France. After his defeat in the 1,500, would he erase some of the doubts about his ability to win the big one? No one could forget his defeat in the Tokyo Olympics 5,000 two years earlier. But many eyes were also on the hometown favorite Lajos Mecser, who had run a fast 13:36.4 in June. Jurgen Haase of East Germany, who had won the 10,000 earlier, was also considered a potential winner. And Harald Norpoth, third in the 1,500 and third in the Tokyo 5,000, was always a factor in the big races.

It was Lajos Mecser who did most of the leading in this race. He led the field through 4K at a relatively comfortable 14:05 speed: 2:51, 2:45, 2:50, 2:49. Fellow Hungarian Kiss took over from Mecser after 4K. The real race began with 500 to go, when Norpoth made his bid for home. The West German was clearly worried about Jazy’s famous kick.

|

| Harald Norpoth, who won a bronze in the 1,500 and a silver in the 5,000. |

Norpoth was able to drop everyone except Jazy. Unlike his nervous performance in the Tokyo race, Jazy’s tactics were patience personified. He waited and waited. Only in the final straight did he make his move. He passed Norpoth quickly and had a convincing 1.2 second margin by the tape. Both Norpoth and Jazy had run the last K in under 2:28.

The race for third was just as exciting. Only 0.4 of a second separated the next five runners. Bernd Diessner of East Germany was just able to hold off Derek Graham for the bronze, with Hungarian Mecser finishing in the same time as Graham.

So Jazy won a second Euro title to go with the one he earned in the 1962 1,500. He had enough confidence in his kick to wait until the very end to use it. Norpoth had tried to nullify this kick by going early, but the Frenchman was just too strong.

1. Michel Jazy FRA 13:42.8; Harald Norpoth WG 13:44.0; 3. Bernd Diessner EG 13:47.8; 4. Derek Graham GBR 13:48.0; 5. Lajos Mecser HUN 13:48.0; 6. Bengt Najde SWE 13:48.2.

10,000

Gaston Roelants of Belgium was almost everyone’s favorite. In 1965 he had set a WR for the Steeplechase and a European record for the 10,000 (28:10..6) He was also one of the best cross-country runners in the world. And best of all he had run 28:20 in Oslo earlier in the season. There was no one in he field who could match his Euro record. Hungarian Lajos Mecser, who was competing in front of his own crowd, was probably the one most likely to give the Belgian a race.

|

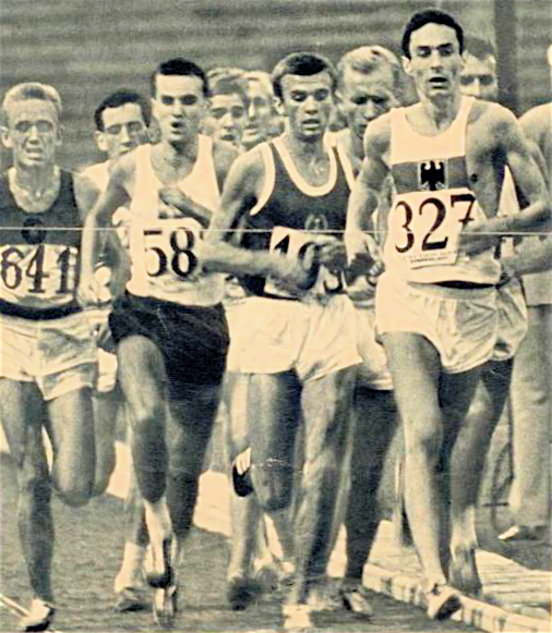

| Haase 493) bides his time onthe shoulder of Letzerich. |

The first 5,000 was on the slow side: 2:50, 2:52, 2:52, 2:53, 2:53. West Germany’s Letzerich did most of the leading. Roelants took the lead in the sixth K (2:55) when the pace slowed even more. Then he ran 2:47 for the next one, opening up a small gap of 10-12m. At 18 laps he was caught by Mecser—much to the delight of the Hungarian crowd. Soon the duo was joined by Jurgen Haase of East Germany, Mikityenko of the USSR and Brits Allan Rushmer and Bruce Tulloh.

The Russian then took over the lead. The 8th K was run in 2:56. Then Mikityenko increased the pace and broke Roelants. At 9K (25:49.8) the Russian’s 2:52 pace had dropped the two Brits. Mecser made his move with just over a lap to go. He didn’t have the lead for long as Haase passed him with 300 to go and held on to win by a full second with a 58.4 last lap. Mikityenko was a comfortable third.

The Lydiard-influenced East German was a surprise winner. At 21 this was his first major competition, although he had won the Euro Junior 1,500 and 3,000 two years earlier. Mecser, who was ranked 5th in the 10,000 in 1965, ran a PB by 4 seconds. Roelants, after his mid-race bid for gold, finished 8th, almost 34 seconds behind the winner.

1. Jurgen Haase EG 28:26.0; 2. Lajos Mecser HUN 28:27.0; 3. Leonid Mikityenko USSR 28:32.2; 4. Manfred Letzerich WG 28:36.8; 5. Allan Rushmer GBR 28:37.8; 6. Bruce Tulloh GBR 28:50.4.

Marathon

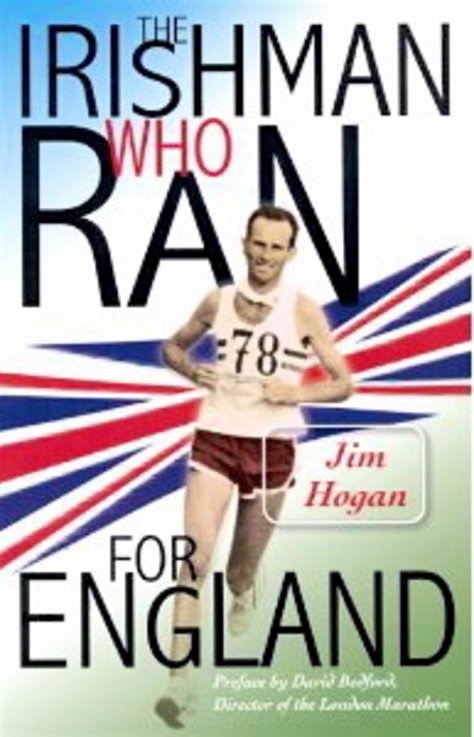

There was no clear favorite in this event. The field contained experienced marathoners like Vandendriessche of Belgium and Kantorek of Czechoslovakia. The Russians were not well known, but they were expected to be contenders. And then there was Jim Hogan, the Irishman who had the temerity to run to the turnaround with Abebe Bikila in the Tokyo Olympic Marathon, only to drop out well before the finish. The highly talented Hogan was always up with the leaders, but he often wasn’t around at the end of the race. He had dropped out of two races both in the last Euros and in the last Olympics.

|

| Jim Hogan's book. |

Indeed Hogan was in the lead at 30K with Hungarian Gyula Toth. But this time he managed to escape his competition and was soon on his own. “I just seemed to float away without any real trouble,” he told Neil Allen. (Times, Sept. 5, 1966) Hogan’s lead gradually increased till he had a 180m lead at 35K. This time he didn’t drop out and went on to a 1:39 victory over the Belgian veteran Vandendriessche, who passed Toth in the later stages of the race.

This was Hogan’s finest hour. He had often been vilified in the press for not finishing races. This time he was also the centre of another controversy as he had recently switched his citizenship for Irish to British. The Irish were none too pleased. Vandendriessche (34) duplicated his second place in the 1962 Euros. Toth (29) put in his best performance in a major meet.

1. Jim Hogan GBR 2:20:04; 2. Aurele Vandendriessche BEL 2:21:43; 3.Gyula Toth HUN 2:22:02; 4. Carlos Perez SPA 2:22:23; 5. Anatoliy Skipnik USSR 2:23:14; 6. Anatoliy Sukarov 2:23:33.

2 Comments