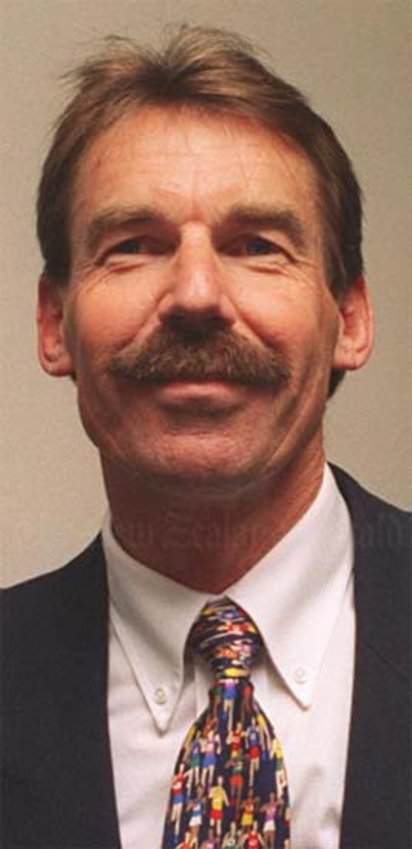

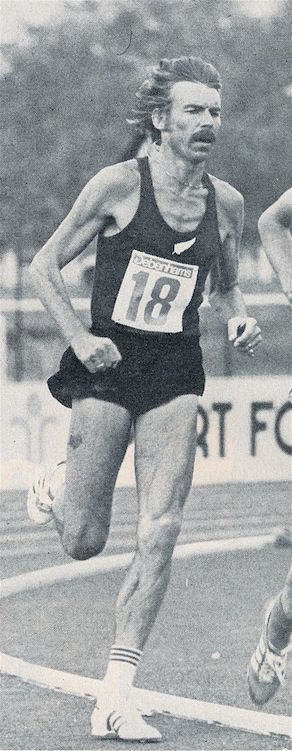

Dick Quax Profile

1948-2018

6’0” (183 cm), 140-143lbs (65-66 kg)

|

Dick Quax is an important member of the New Zealand distance-running pantheon. He stands as an equal alongside the likes of Lovelock, Halberg, Baillie, Magee, Snell, Davies, Walker and Dixon. An Olympic silver medal, a Commonwealth silver medal and a 5,000 world record were his greatest achievements. There would surely have been more medals had he not been prevented from competing in major games by injuries and an Olympic boycott. He was also versatile, running the 1,500 in 3:35.9 yet posting the second-fastest ever 15,000 (43:01.7) and a 2:10:47 marathon when the world bests were 42:54.8 and 2:09.01. Quax’s crisp running gait was unusual in that he landed further to the front of his foot than most runners.

***

Although undeniably a Kiwi, Dick Quax was born in Holland. His Dutch parents, having survived Nazi occupation in World War 2, emigrated Down Under in 1954 when Dick was six. He grew up in Waikoto, which is 70 miles south of Auckland on the north island. The sports environment of New Zealand soon had him playing rugby; later he found he had an unusual ability to run. Inspired by Peter Snell and Murray Halberg, both of whom he saw race in the early 1960s, he began training seriously in 1964 at age 16, using the principles of Arthur Lydiard and building up to a weekly mileage of 100.

In 1968 he joined up with John Davies, the 1964 Olympic bronze medalist for 1,500. Davies remained his coach throughout his career and later became a business partner. With Davies he continued to use Lydiard principles, except that he avoided the bounding exercises to protect himself from injury. He gradually trained harder building up to where he was comfortable with a weekly mileage of 120-130.

Beating Keino

|

|

Hanging on to Keino in the last lap of the 1970 Commonwealth Games. |

In a time where the glory days of New Zealand running seemed to have passed, Quax emerged as a new star in 1970 when he defeated the great Kip Keino in a March 18 Mile in Auckland. Admittedly Keino was somewhat below par from travel, but the spirits of New Zealanders were revived by the sight of the 22-year-old powering away from the Olympic champion in the last lap. Quax’s time of 3:57.8 was a personal best and would turn out to be the 10th fastest Mile of 1970. Quax took this victory for all it was worth: “Sure he didn’t have much time [to recover from jetlag],” he told Ivan Agnew, “but I beat Keino. Nobody can take that away from me.” (Kiwis Can Fly, p. 31) Later he admitted that the win gave him a lot of confidence.

Now New Zealand’s new middle-distance star, Quax went to Europe to prepare for the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh. The brash 22-year-old was full of confidence telling people he was going to give Keino the race of his life. And indeed he lived up to his boast.

Commonwealth Silver

An indication that he was in his best-ever form came a few days before the Games at Grangemouth, where Quax won a 3,000. His time of 8:06.6 was mediocre, but the weather was atrocious and he beat Ben Jipcho, holding him off with a last lap of 58.2. Neil Allen of The Times was impressed with this new Kiwi: “He has something of the “beat me if you damn well can’ look of his great countryman Murray Halberg. (July 13, 1970)

In the Commonwealth 1,500 final, Keino set a fast pace, and Quax was right behind him after 300m. The Kenyan reeled off laps of 57.6, 57.4, 57.0 but could not escape Quax. The 3:35 pace left the rest of the field in a bunch 30m back. Quax looked as comfortable as anyone could on the last lap of a 1,500--relaxed and crisp. Entering the last bend, Keino made his final effort to drop Quax, gradually opening a three-meter gap by the time they entered the straight. Quax was done and had to watch the gap lengthen to nearly 10 meters at the finish as Keino continued to apply the pressure. The Kenyan had run the last 300 in a slowish 44.3, but his 2:52 pace to 1320 had done enough damage to Quax. Keino 3:36.6; Quax 3:38.1. These times were the second and third fastest in the world for 1970. Keino said afterwards that he had to push the pace from the start because he was worried about Quax. With this one race Quax had established his international reputation. It had been a brave run.

Three days later, Quax also ran the 5,000 in the Games, finishing seventh in 13:43.4, a full 20 seconds behind Stewart and McCafferty. Still, a 13:43 clocking was encouraging, and the 5,000 would gradually become his main event. After the Games, Quax tried to get over to the continent for some races, but promoters weren’t willing to pay his airfare. His 1970 season was over.

Injury

After such a great year, 1971 was disappointing. It started well with a promising fourth place in an indoor Mile in San Diego (3:58.9). He then ran a 3:57.3 outdoor Mile in Auckland. His form was good enough to get him to Europe, but fighting injuries, he couldn’t reach his 1970 form. He competed in the British AAA championships, but failed to get through the heats “looking rather apathetic.” (Times, July 24, 1971)

Quax was in better shape for the New Zealand 1971-72 season. He broke the National 3,000 record and recorded the fastest 1,500 of the season with 3:39.4. In February he set a national record for 5,000 with a 13:35 PB. “I knew that I could go a lot faster because…I was out there on my own,” he told Jon Wigley. (Athletics Weekly, Aug. 13, 1977) After some intense competition with Tony Polhill and Kevin Ross, Quax maintained his status as New Zealand’s premier middle-distance runner. He was certainly his country’s best prospect for the Munich Olympics.

He looked in reasonable form before the Olympics with an 8:24.3 Two Mile time—in fifth place and ten seconds behind Viren, who set a WR of 8:14. Then just before the Games he developed severe shin splints and was unable to train. Although still able to run his 5,000 heat, he finished a desultory ninth with 14:35.2. He told Jon Wigley: “I was almost crippled. I could hardly walk, yet alone run. In fact, after the Olympics I couldn’t walk properly for ten days. I believe that…I was good enough to finish in the first six in the 5,000, but being totally realistic I would never have finished with a medal. I ran only to justify being there.” (AW, Aug. 13, 1977) Quax’s shin-splints problem was to dog him intermittently for three years until he finally underwent a decompression operation.

Banner European Season

|

In 1973 he was fit enough to undertake a European tour. At first, his prospects look grim. On his way to Europe he entered a Mile race in Victoria, Canada, but had to scratch because of his shin splints.

However, two months later he was able to race again. He began with a 1,500 PB (3:37.4), finishing third behind Jipcho and Dixon. Six days later in Helsinki he had a big win with a 5,000 PB of 13:27.2. This win was a great boost as he finished ahead of Olympic champion Lasse Viren, who was second in 13:28.8. Viren took the lead over the last lap, as he had done the previous year in the Munich Olympics, but Quax was able to hold on and then pass the Finn in the last 20m. In Stockholm a week later he improved his 5,000 PB to 13:18.4 in placing second to Emil Puttemans (13:14.51). A fourth PB came in a 3,000 in Copenhagen, which he won in 7:46.2.

Next came what was probably his best run of the season—in a 4x1,500 relay. The race was set up for the Kiwis to attack France’s 1965 record of 14:49.0. Quax was to run the anchor leg. After Tony Polhill (3:42.9), John Walker (3:40.4), and Rod Dixon (3:41.2), Quax was the only one to break 3:40 with a fine 3:35.9—John Walker called it “one of the greatest solo races of his life.” (John Walker, Champion, p. 59) The team decimated France’s record with 14:40.4, but the record was not ratified as one of the other teams had not carried the baton for the whole race.

Quax was still in great form when he went to London in September to race Ben Jipcho over a Mile. Jipcho had the second-fastest ever Mile (3:52.17) and was the new world Steeplechase record holder (8:13.91). Quax had come close to the Kenyan earlier when he ran 3:37.4 behind Jipcho’s 3:37.0. Now he had another chance. The two were close together down the back straight of the last lap, and both tried to get the inside round the last bend. They bumped with 200 to go, and Jipcho suffered the worst of it. Quax appeared to have the race won, but Jipcho stormed back, caught Quax 15m out, and won the race in 3:56.2. Quax’s consolation was a 3:56.37 PB, though he did get attacked in the press, not only for his collision with Jipcho but also for pushing aggressively between two British runners.

Stress Fracture

After such a fine Euro tour, Quax was looking forward to performing well in the Commonwealth Games in front of a home crowd. The problem with his shin splints had not returned since the early summer. So he was able to train well to the end of 1973, when he produced an encouraging 5,000 on January 3. His time of 13:01.4 as he passed Three Miles was a national record and his final 13:24.4 showed he was in great shape for the January games. But misfortune struck just before the games: a stress fracture in his right foot forced him to withdraw at the last moment. “Two days before the opening ceremony,” he recalls, “I went out in the morning and my foot was really sore…in the afternoon I couldn’t run at all.” (Wigley) Neil Allen described Quax’s condition after his withdrawal: “He was in the depths of depression, trying hard to be philosophical, even though he suspected that some New Zealanders felt he had opted out psychologically.” (Times, July 14, 1976)

Although he didn’t run in Auckland, Quax still left his mark on the Games. He was expelled from the athlete’s village after writing a newspaper article criticizing the tactics of the Kenyans in the 10,000. The justification for this expulsion was an agreement he had signed that he would not write or comment publicly on the Games.

As it turned out, 1974 was a write-off as far as competition was concerned. He did go to Europe, but a 10th place in a 10,000 race in Paris is his only documented race. But he battled on, still dealing with shin splints. His hopes were raised by an easy 5,000 win (13:34.6) in the inaugural New Zealand Games in January of 1975.

Surgery

Back in Europe, he started suffering again from shin splints. So after finishing 5,000 races in 9th and 7th positions and running around 13:40, he decided to go home and undergo surgery. “It’s a fairly simple decompression operation,” he explained. “Around the shin muscle is a fascia that doesn’t stretch as the muscle grows…. It was a matter of cutting through the fascia an sewing it up again, thus allowing the muscle room to move.” (Wigley, Athletics Weekly) Three hours and 34 stitches later, his shin-splints problem was solved for good. According to Ivan Agnew, the surgeon was astonished that Quax had been able to run at all. When the fascia was cut, the shin muscles “popped out like sausages and in some cases had attached to the sheath instead of operating independently inside.” (Agnew, Aim High, p. 40). He was running within two weeks and up to 100 miles a week after ten weeks. The Montreal Olympics were less than a year away.

Montreal Preparation

|

|

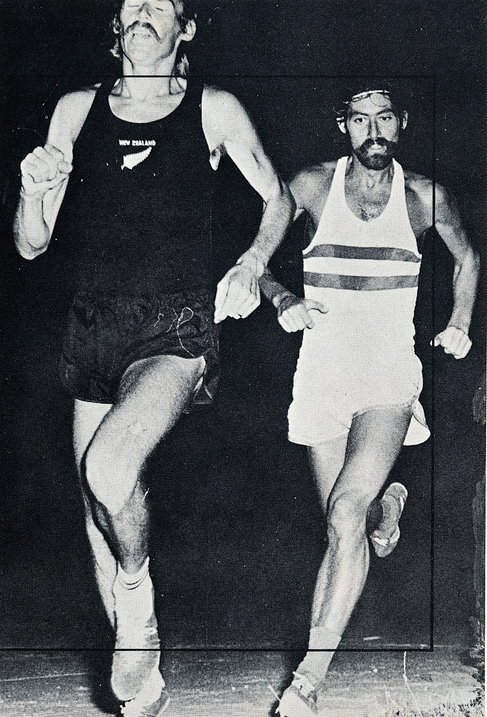

Quax leads Dave Bedford in a New Zealand race. |

Now free of pain and able to train without interruption, Quax was able to get himself in the best shape of his life for the Montreal Olympics. During that Olympic build-up, in the New Zealand track season in early 1976, he ran 3:58.6 for the Mile, 13:24.8, 13:32.0 for 5,000, and a solo 27:55.2 in his first serious 10,000.

After another four months solid training, he went to Europe—against the advice of his coach John Davies—to tune up for Montreal. While in Scandinavia he recorded three personal bests. First he ran 3:36.7 for 1,500 behind Dixon (3:36.1) in Oslo. Then in Stockholm he surprised everyone by running just 0.1 of a second outside Emiel Puttemans’ world 5,000 record. Quax was pushed hard in the race by German Klaus-Peter Hildebrand and finished only half a second ahead with 13:13.10. According to John Walker, who won the 1,500 in this meet, Quax “could well have broken [the record] had he know he was going so close.” (, p. 111)

Quax discussed the race with Neil Allen: “Gordon Pirie, who now lives in New Zealand, was shouting out my time, and normally I can hear him, but I missed the laps he was trying to give me, and official splits don’t mean much to me. I was taken through the first for laps by a friend in 4:12 and I was in the lead at 3,000 in 7:59. The pace was a shade too slow between 2,000 and 3,000; otherwise the world record would have gone.” (Times, July 14, 1976)

Finally in Zurich he ran his fastest-ever Mile in 3:56.23, finishing fourth. Thus Quax arrived in Montreal as one of the favorites for the 5,000 title.

Montreal 10,000

This was Quax’s fourth major games. In the first one he won a Commonwealth silver, but the next two saw him struck down with injuries: he hobbled round the 5,000 in Munich to finish ninth; he had to withdraw from the Auckland Commonwealth Games with a stress fracture. Surely, he was due for some good fortune this time, especially since he was in such great form.

But disaster struck soon after he arrived when he caught a virulent stomach virus from his wife. He was so distraught that he burst into tears. After telling his coach he couldn’t run the 10,000 (he had lost 5kg overnight), he changed his mind and lined up for the third heat. He managed to stay with the lead bunch for 16 laps, but then a surge in the front left him struggling. Not one to give up, he kept going and ran a very brave 28:56.92 for ninth place. He could not bear to go to the stadium to watch the final. At least he still had his best event to run. Hopefully he would have recovered by then.

Montreal 5,000

Just two days later, Quax was on the start line again for the first heat of the 5,000. According to Ivan Agnew, “He wanted to reassure himself that he was indeed recovered and to assert his influence on his rivals.” (Aim High, pp. 92-3) He won his heat comfortably in 13:30.9, with a 56 last lap that took him from fourth to the front. He had clearly recovered his strength, but his stomach was still very sore.

Another two days later, he was one of 14 finalists on the start line. There were some very good runners beside him, including Hildebrand, Viren, Foster, Stewart and of course his fellow Kiwi Rod Dixon. It was to be one of the great races of all-time.

Quax stayed in the pack in the early stages. The pace was brisk but not too fast—about 13:17-13:20 pace. The pace slowed during the third kilometer with laps of 68.6 and 67.0. This slowing brought Quax out of the pack. Despite already feeling sore in his stomach, he took the field through the next lap in 63 but then dropped back into the pack when Hildebrand took over. Viren was soon in the lead and he upped the pace back to 62.9. When Viren took over, Quax easily moved up from fourth past Dixon and Hildebrand to sit on Viren’s shoulder.

|

|

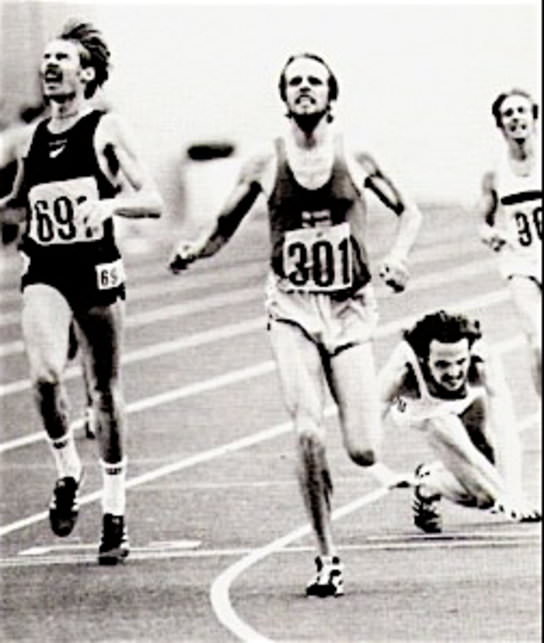

1976 Olympic 5,000 final: Quax has dropped back to sixth at the bell behind Viren, Stewart, Foster, Dixon and Hillbrandt. |

The next move came from Foster, who moved past Quax into second and with two laps to go challenged Viren. Viren accelerated round the bend to fend off Foster and then the pack disintegrated. Only six were left, including Quax in third. But coming into the straight to begin the final lap, three runners passed Quax and he found himself in sixth place as the bell sounded.

He stayed on the inside round the bend and halfway down the straight before looking behind and swinging out. He made this move rather late and had even let a small gap develop in front of him. He was 3-4 meters behind the leader, Viren, but there were four other runners in his way. By the 200 mark he had passed Stewart and closed the gap slightly. He really sprinted from the crown of the bend and was past Foster in a flash. So far he had not run too wide, but coming into the straight there were three runners almost shoulder-to-shoulder ahead: Viren on the inside, Hildebrand beside him, and Dixon on Hildebrand’s shoulder.

|

|

Just under 200 to go. Quax is now in fourth, but there are still two runners between him and Viren. |

Quax had to move out toward the third lane. Meanwhile Viren, keeping his form perfectly, was running tight on the curb. Dixon then began to lose ground, so Quax had to move even further out. Once past Dixon he was neck-and-neck with Viren and Hildebrand as they approached the straight. Then Hildebrand began to fall back, but Quax was still in the second lane as they entered the straight.

|

|

Quax draws level with Viren. Note how much wider than Viren he is running. |

“I slightly edged in front of Viren,” he recalled later. “I thought, ‘I’ve got this race won,’ and for one instant through my mind went the thought ‘I’m the Olympic champion.’” (Internet video, “Kiwis at Montreal, 1976”) In the last 120 m, Quax, in catching Viren and running wide, had covered a good six meters more than Viren. And the effort began to tell. He was unable to pass the Finn and then fell back, finishing about three meters behind. A brilliant silver medal, especially in view of his recent illness. But his last-lap tactics had surely lost him the gold medal.

Post-Race

|

|

Viren just holds off Quax at the end of the Olympic 5,000. |

Soon after the race, Quax had this to say: “The man I feared most coming off the last bend was Rod Dixon. With about 120 to go I noticed he was in a box and I made my kick from there. I was surprised that Lasse, who hasn’t such a fast 1,500 time as myself, had such a good kick.” (Watman, AW August 12, 1976) But it wasn’t really a good kick, but a sustained finish. A careful look at the film of the race shows that Viren didn’t really kick that hard; he merely maintained his speed in the last 200. He passed the 200 mark in 12:57.60, which means he ran the last 200 in 27.2, a little slower than the previous 200 (27.9). This 27.2 time was not that fast for a tactical 5,000 in 1976. Quax had run his last 200--or a little more that 200 since he ran the last bend wide—faster, but he didn’t win. In fact he was almost exactly the same distance behind Viren at 200 as at the finish.

“I was bitterly disappointed,” he recalled. “It was so close: it could have been a gold medal. But all these years later, with the benefit of hindsight, I don’t have any regrets at all.” (Internet video, “Kiwis at Montreal, 1976”)

Europe Again

Following the games, Quax made use of his fitness. First, he beat Viren convincingly in a Two Miles in Philadelphia (8:17.08) before heading for Europe. He didn’t wait to recover from jetlag and raced two days after his Philadelphia Two Miles in Edinburgh: a ninth place in a Mile in 4:01.2. Three days later her was in Stockholm to race Lopes over 10,000. Although he couldn’t match the Olympic silver medalist’s strength, he did improve on his 27:55 February time with 27:46.3, just 3.5 seconds behind Lopes. Only Viren and Lopes ran faster in 1976. After a modest fifth place in the British AAA 1,500, he had a good 5,000 win in the Zurich Weltklasse (13:24.07), this time beating Lopes. But he was beginning to lose his sharpness, and his only other good race was a fourth behind Walker, Wessinghage and Coghlan in the ISTAF Mile. Season over. As well as his Olympic medal, he could look back on several PBs—in the 1,500, the Mile, 5,000 and 10,000. He ranked 10th in the 1,500, 9th in the Mile, 1st in the 5,000 and 3rd in the 10,000.

1977

After a hectic Olympic year, Quax had a fairly quiet time in the 1977 New Zealand season, which he called “very unnoteworthy.” (Wigley) His best times were 7:59 for 3,000 and 3:43 for 1,500. His toughest race was a 5,000 against a young German, Karl Fleschen. Quax managed to beat him, but only by 0.1 of a second with 13:31.9. His eyes were clearly on European season competition, especially the 5,000 world record: “I had so little motivation after the Olympics. I wanted something to motivate myself with, and the goal of a world record was the factor.” (Wigley. Athletics Weekly)

Once the New Zealand season was over, he started training harder than ever and then headed to Colorado for altitude training with Frank Shorter. “”I think it was successful,” he told Jon Wigley. “Maybe I was pretty fit anyway, But I believe that the altitude training helped…. I didn’t train hard up there at all. We did 7 or 8 miles in the morning—very,very easy at about 6:20 per mile pace—and my track sessions at night were very slow compared to what I do at sea level.” (Wigley) He began competition in late June with a PB 3,000 of 7:45.11; he would never run 3,000 faster. Then he won the 5,000 in the Helsinki World Games with a fast 13:19.4, beating Ian Stewart.

5,000 World Record

|

It was cool and breezy in Stockholm on July 5 when the race started. Dixon took the field through in 2:39 and 5:18 and led almost until 3,000, when he developed a cramp. Quax was in the lead at that mark, passing in 7:56, which was 4.8 seconds slower that Puttemans’ time at this point. Quax was beginning to think that any chance of a world record was gone when Fleschen surprisingly took over the pacemaking at 3.8K and increased the pace a little. Fleschen and Quax passed 4K in 10:38.9. Still the fourth 4K had been slow (2:42.9), so a last K of 2:34.0 was needed to break the world record. With 500 to go, Quax made his effort and opened up a small gap on Fleschen. At the bell he needed a 59.1 to break the record, and this was exactly the time he ran. Quax just beat Puttemans’ 13:13.0 record with 13:12.86 to become the first new Zealander to hold the 5,000 world record. Afterwards he acknowledged Fleschen’s help.: “We had a nice pace all the way. I have to thank Fleschen for forcing the pace when I had that bad spell. If he hadn’t done that, I wouldn’t have broken the record.” (Track & Field News, Sept., 1977)) Fleschen was only a second behind Quax at the end.Clearly pleased with his form, he set up an attack on Puttemans’ 5,000 world record, choosing what must have been his favorite venue, Stockholm, and enlisting Rod Dixon to help with the early pace, hopefully to cover 3,000 in 7:51-2. The only likely challenger in the race was 22-year-old German Karl Fleschen, who after his big battle with Quax in New Zealand, had won the European indoor 3,000 title. Quax developed a cold just before the attempt, but he decided to go ahead nevertheless, despite feeling he had lost a little of his altitude-induced form.

Like many other record breakers, Quax suffered a letdown after his great run. He was 6th in a 1,500 in Warsaw and sixth again in a Mile in Dublin. Even at his 5,000 distance he was below par, finishing 5th at the Ivo Van Damme meet. It wasn’t until September 9 that he ran well again, just over two months after his world-record run. Although he didn’t win the 10,000 race in London, he ran a lifetime best of 27:41.95 for fourth place behind Foster (27:36.62), Rono and Tebroke. After passing the halfway mark in 13:57, Quax was still with the leaders with six laps to go. But finally he couldn’t cope with Rono’s surges and dropped back. Still this was an encouraging performance: he was 11.5 seconds outside Kimombwa’s world record and he was past his peak. The 10,000 record looked like a natural goal for 1978, when Quax would be 30.

Disappointing Year

This was not to be. The best he could do over 10,000 in 1978 was a 28:04.7 in Stockholm—in seventh place. He had run a 13:26.0 5,000 in January, but he wasn’t winning races Down Under. Then he had placed fifth in a Mile in San Diego behind Coghlan and Scott. In Europe he was 7th in the AAA 5,000 and 7th in the Bislett Mile. Injury problems were back, and after finishing a disappointing 9th in the Commonwealth Games 10,000, he left Edmonton without even attempting the 5,000.

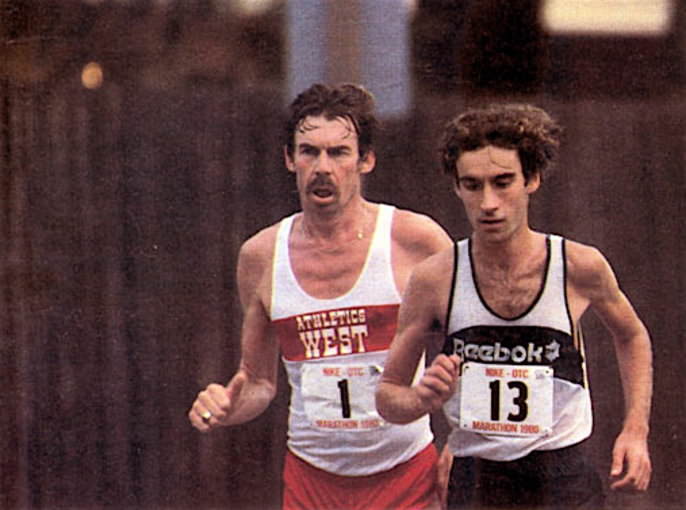

Longer Distances

Quax’s focus now moved to longer distances. The next year he ran what was described then as the fastest marathon debut ever. In the September 1979 Nike/OTC Marathon he placed fourth in 2:11.13. The next year he won the race by 12 seconds in 2:10:47. This was the fastest time he ever ran. He would surely have been in the medals in the Moscow Olympics but for a boycott by the New Zealand team. Still, there was a second notable run in 1980, a 15K track race at Stanford, California. His goal was to beat Jos Hermens’ world record, and he got very close with 43:01.7, just 6.9 seconds too slow.

Then, as his competitive career wound down, Quax began to coach. His most notable success was with Lorraine Moller. He based his coaching on Lydiard’s ideas: “Lydiard training is not a recipe but a balanced approach to endurance training which needs to be tailored to the individual.” (Christopher Kelsall Interview) Quax has produced coaching videos that can still be accessed on the Internet.

He also went into politics, first as a Manukau City Councillor (2001-2007) and then as an Auckland City Councillor. He twice ran unsuccessfully for parliament.

Conclusion

A dedicated trainer and a fierce competitor, Quax became one of the foremost middle-distance runners of the 1970s, Talented and ambitious, he began serious training early at 16 and was well-served by his coach John Davies from age 18. Tall for a distance runner, but very light, he ran with an unusual style that saw him on his toes early. He had a very economical running action and a noticeably brisk tempo. Thus in the later stage of a race he often seemed more relaxed than those around him. His longtime shin problem may well have originated from his running style. Two silver medals indicate his competitive qualities and his two fast 5,000s, one a tenth slower and one a tenth faster than the world record, are testament to his class. Although dogged at times by illness and injury, he never gave up and earned the respect of his peers.

2 Comments