Jean Wadoux Profile

b. 29 January 1942

|

|

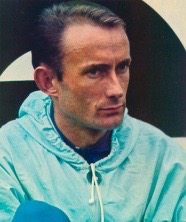

Jean Wadoux "Regard clair et aigu" Michel Jazy |

Frenchman Jean Wadoux emerged in the 1960s as one of the world’s finest middle-distance runners. He was a worthy successor to Michel Jazy, in whose shadow his early career developed. His greatest achievement was a European 1,500 record of 3:34.0 in 1970. At that time it was the second-fastest 1,500 ever recorded. Wadoux also ran the 5,000 in 13:28.0. His competitive record was excellent, although critics have noted his poor record in major competitions. This is unfair. A closer look at his two Olympics and three Europeans shows that he performed well in two of these meets and was handicapped by altitude (Mexico) and by an injury in two others. Only in the 1966 Europeans did he disappoint. Wadoux won many races for his country in international matches and was French national 1,500 champion for seven consecutive years. When he moved up to the 5,000 later in his career, he posted impressive wins over Keino and Clarke and won a European silver medal in his last year of competition.

Consistency was a feature of Wadoux’s long career (1961-1971). Every year he performed well and rarely had a poor race. This consistency was achieved through strong self-discipline. An introvert and deep thinker, Wadoux admitted that he was “too serious in a lot of areas, both athletic and professional,” while adding that this seriousness was both a fault and a strength. He also admitted to suffering from “too much nervousness” before important races—something he had difficulty mastering. He liked solitude and preferred to train alone. On the other hand, he relied on his family for support and said he would have ended his career early if it had interfered too much with family life. He maintained his job in tax collection throughout his running career, sometimes having to cut back on his running to perform his work duties.

---

Jean Wadoux grew up in Ramecourt, a village in Northern France near Calais. As a child he was frail and for a time was exempted from physical education. When he started sports he quickly showed a taste for running. When his father died, he left school at 15 and began work in tax collection. One of his superiors encouraged the young Jean to run. Soon he was showing unusual ability.

Later on, Wadoux returned to school and passed his diploma at age 18. The next year, 1960, he became the French Junior 1,500 champion. That year he continued his winning ways with two Junior international wins against Spain (3:58.0) and Belgium (3:54.1, a French Junior record). He claimed later that he was not training seriously at this stage: “I didn’t start training hard until I was 20. Before that I only ran cross-country twice a week, there being no track nearby. It was extremely difficult to compete in weekend races because I worked some of the weekends.” (MA) While Wadoux was making his mark as a Junior, Michel Jazy was earning a silver medal at the Rome Olympics. Though almost 16 seconds slower at this point, Wadoux was to become Jazy’s closest rival in France. But this was several years away. First there was military service in Algeria.

The French authorities allowed Wadoux to train during his military year, and he went on to win both the French and International 1,500 military titles in 1962. He was also able to obtain leave to run in three international matches against Switzerland (2nd in 3:47.3), Belgium (1st, 3:57.2) and Holland (2nd in 3:50.8). As well, he placed second in the French Championships behind Clausse (3:51.2). His best time was the 3:47.0 he ran to win the International Military Championships in Holland. This was an improvement of 7.1 seconds over 1961.

Commitment

|

|

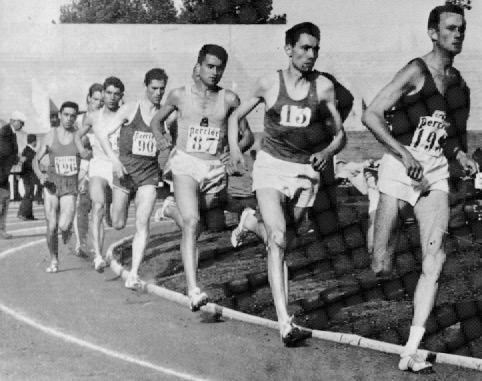

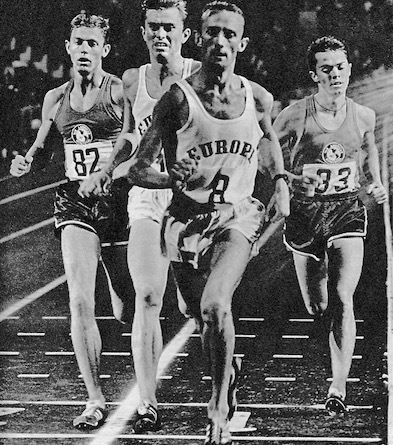

French 1,500 Championship. Wadoux leads Bernard and Jazy. |

The successes of 1962, while he was in the military, led him to a decision to become a serious runner: “After my demob in March 1963, I decided to focus full-time on my sporting career, basing myself in Paris where the facilities for my training regime were available. I didn’t quit my job, so sometimes I had to sacrifice my training for work obligations that were important to my future.” (MA) With his new resolve, he improved another 5.3 seconds in 1962 and was starting to get closer to the two top French runners, Michel Bernard and Michel Jazy. His talent was such that people were beginning to talk of him as the logical successor to Jazy. Early in the 1963 season, he was beaten by Lurot over 800 and Nicholas over 1,500, but his 1,500 time came down to the 3:42s. He ran a new 3:41.7 PB in the French Championships behind Jazy (3:37.8, a European record) and Bernard (3:38.7). In this fast race, Wadoux had led through 400 in 58.1, before Bernard took over. Later Wadoux referred to this race as one of the seven highlights of his career.

He did earn one major title that year, winning the Mediterranean Games 1,500 (3:54.4). At the end of the season, Wadoux showed his class again by helping and ailing Michel Jazy win an international team race against the USSR: Jazy was “tactfully nursed home to victory by his talented second string,” reported the Times (23 Sept.1963). Both runners were clocked at 3:44.3.

Room at the Top?

Wadoux had now achieved international class (ranked 11th in the world for his 3:41.7), but Jazy was still improving and still dominating the French scene. The two runners quickly became friends. Both shared the same attitude toward training, preferring to run away from the track in natural surroundings. Wadoux, who was self-trained, has given three reasons for avoiding the track: his preference for training according to how he feels rather than according to a watch; his tendency to get injured from track running; his predilection for running in natural surroundings.

The Olympic year had Wadoux training toward a peak in October. Surprisingly, however, he showed impressive early-season form with an 800 in 1:49.0 800, a French record over 1,000 (2:18.6) and a PB 3:40.8 for 1,500 behind Jazy (3:39.8) in mid-June. “I hit my form too early,” he recalled later. (MA) In the French Nationals, he showed more improvement by beating Michel Bernard for the first time in a major race. Jazy won comfortably in 3:41.5, but Wadoux, his Olympic selection assured, was not far behind in 3:42.4. Bernard clocked 3:42.8.

The next month he was up against one of the favorites for Tokyo: Alan Simpson of Britain. Wadoux ran a brave race and was in front until the final straight, where he had a “prolonged battle” (Times, 11 Sept. 1964) with Simpson, eventually losing 3:45.0 to Simpson’s 3:44.7. Following this, Wadoux went to Tokyo with confidence. This confidence was enhanced a few days before his heat by a fast 1,200 time-trial in 2:54+.

Tokyo Final

|

|

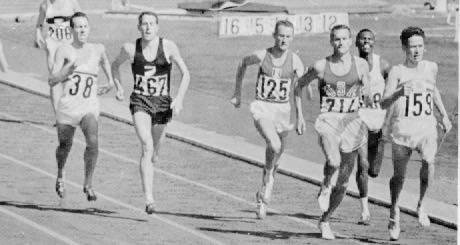

Tokyo 1,500 semi-final. Simpson (159) and Burleson have passed Wadoux (125). |

Alan Simpson was coincidentally in Wadoux’s 1,500 heat, as were Odlozil, Allonsius, and Valentin. Wadoux ran well to finish second in 3:43.0 to Simpson (3:42.8), comfortably ahead of the last qualifier (Allonsius). His semi-final field was daunting: Allonsius, Simpson, Burleson, Davies, Keino, O’Hara and May were all fighting for the first four positions. Burleson and Simpson were the class of the race, both finishing in 3:41.5. Behind them there was a very tight finish with four runners finishing in the same 3:41.9 time. “With 80 to go I was in the lead,” Wadoux recalled. “Then Burleson and Simpson came by like rockets.” (MA) There’s no doubt that Wadoux ran the best race of his life so far to finish fourth behind Davies of New Zealand and in front of Keino and Allonsius. The 22-year-old was in the Olympic 1,500 final.

But he was exhausted. The supreme effort of beating Keino and Allonsius just two days after his 3:43.0 heat was too much for him. In the final, he did manage to hang on at the back of the field with laps of 59.3, 62.2 and 58.8, and when the leader Davies hit the 1200 mark in 2:59.3, he was only one second back—but still in last position. Whereas everyone else accelerated, Wadoux could barely maintain his speed, his last 300 taking 45.1 seconds. Finishing last in ninth and running last for the final 1,200 of the race, he had nothing left to answer winner Snell’s 38.6, or even Odlozil’s 39.9.

Still it was quite an achievement to make the 1,500 final in his first Olympics. He had run brilliantly in the semi-final. Based on this alone, his 1964 season must be deemed a success, even though he barely improved his 1,500 time from 3:41.7 to 3:40.8. This ranked him 17th in the world.

More International Experience

|

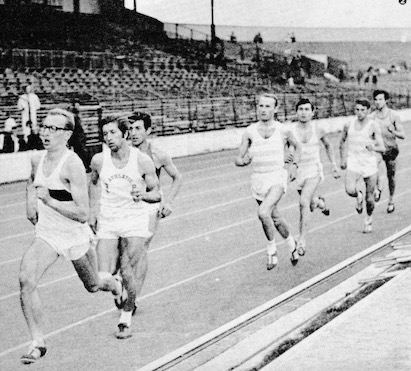

| Wadoux in full flight. |

Wadoux was ranked only 26th for the 1,500 the following year. 1965 was an “off year” with no major championships except the European Cup. He ran only 3:41.8, but he had a Mile time of 3:57.2, which ranked him 11th in the world. In this race, held At St Maur on June 2, Wadoux ran second to Michel Jazy, who broke the European record with 3:55.5. He did well to beat Poland’s Witold Baran (3rd in 3:57.4). The following week at Rennes he helped Jazy to a Mile world record of 3:53.6, pacing his friend on lap 2 with a 58.9 lap and finishing back in 6th.

Three days after Jazy’s Mile world record, Wadoux participated in a French attack on the 4x1,500 world record. France had broken the record in 1961 with 15:04.2, but two years later East Germany had won back the record with 14:58.0. The successful attempt was given a good start by Vervoort and Nicholas. Then Jazy ran a fast leg just under 3:40 before Wadoux ran a solid 3:42. The result was a huge new world record of 14:49.0.

It looked like he was going to spend the season running second to Jazy, but his friend got injured and suddenly Wadoux was France’s number one. After winning his first national title (3:42.1), he acquitted himself really well in international competition. In the Six Nations meet in Berne he ran a good third (3:44.6) to Tümmler (3:43.6) and de Hertoghe, and then won the 1,500 (3:45.7) in a match against Spain.

His biggest test in 1965 came in the European Cup. He won for France in the semi-final in Oslo (3:42.3) and then ran both the 1,500 and 5,000 in the final. On the first day he ran a close 2nd (3:48.0) to Tümmler (3:47.7) in the 1,500; on the second day he ran 4th (14:25.8) behind Norpoth (14:18.0), Baran and Derek Graham in a slow tactical 5,000.

Euro Setback

The next year, Wadoux was still France’s second string behind Michel Jazy. Now 30, Jazy was running really well. On June 30, 1966, he ran 3:36.3, well ahead of Wadoux (3:39.4 PB). And a week later Wadoux was still behind Jazy in a match against West Germany where Tummler beat both Frenchmen. Following his second national 1,500 title, while Jazy was absent, he finally finished ahead of his friend in a match against Czechoslovakia: 1. Odlozil 3:37.6; 2. Wadoux 3: 37.7; 3. Jazy 3:38.3. This PB effort bode well for Wadoux in the upcoming Europeans in Budapest. He was clearly in the best form of his life.

But the European 1,500 was a huge disappointment. With three French runners in the final—Jazy, Wadoux and Nicholas—it seemed likely that there would be some pacemaking for Jazy, who was known to be vulnerable to Tümmler’s finish. But Wadoux and Nicholas stayed in the pack as the field crawled though in 59.5 and 2:03.4. The pace was still slow at 1,000 (2:34.1) but it had speeded up by 1,200 (3:02.5). While Tümmler (3:41.9) led Jazy (3:42.4) to the tape, Wadoux languished back in 7th with 3:44.5.

After a French 1,500 sweep in Kiev against the USSR (1. Jazy 3:51.3; 2. Wadoux 3:51.6), Wadoux finally hit form in October. First he beat the top two English runners, Simpson and Whetton in a match against Great Britain and Finland, where according to the Times he “left Simpson and Whetton looking leaden-footed in the home straight.” (2 October 1966) Then he made a major contribution to Michel Jazy’s final race, an attack on the 2,000 world record. “This was a successful farewell as [Jazy] broke the world record (4:56.2),” Jazy recalled. “I was happy to have participated in this festivity.” (MA)

|

| Montreal: Wadoux (8) ran second to American Van Ruden. |

All of France was hoping that with Jazy’s retirement, Wadoux would emerge as their next world-beater. Wadoux did eventually emerge, but the next year he did not meet the public’s expectations that had been built up by the French media. True he ran a three sub-3:40s—one of them (3:39.1) earning him his third national 1,500 title—but he was not winning European races, He lost to Arese and Odlozil in a European Cup 1,500, he lost to American Van Ruden in Montréal, and he lost to De Hertoghe and Garderud in August. It would be fair to say that his season was disappointing. One hopeful sign was his 5,000 meter running. After beating an unfit and retired Jazy in Rennes, he ran a fast 13:43.6 to win from Temu (13:48.6) and Bernard. Wadoux had always said that he lacked the basic speed for 1,500, so clearly he was preparing to move up to the 5,000. At this point, however, he was world-ranked higher for the 1,500 (3rd) than for the 5,000 (20th). So the question for the upcoming Mexico Olympics was over which event to choose. He would have liked to double, but he realised that the altitude in Mexico City would make this impractical.

5,000 Breakthrough

|

|

Paris 5,000: Wadoux (310) tracks Ron Clarke. |

Wadoux spent a lot of time during 1968 at Fort Romeu, adapting himself for the rigours of the Mexico City altitude. This training, together with some cross-country racing early in the year, saw him in good early-season form again in June of 1968. After running two fast 3,000s (7:56.4, 8:00.4), he surprised himself and everyone else in a 5,000 against Ron Clarke at the Jean Bouin track in Paris on June 13. “It was really an adventure into the unknown,” he recalled later. “My best 5,000 time from the previous year was 13:43 and change. I had run only a couple of 3,000s, and I didn’t know what condition I was in. I asked Clarke to set the pace with 64-second laps. He thought I was bluffing and didn’t take me seriously.” (MA) Clarke did take the first few laps, but then Wadoux took over at 2,000 and began to open up a gap. He was able to hold on to beat the great Australian 13:29.6 to 13:31.8. This was a 14-second PB and confirmed that his Olympic preparation was going well.

Wadoux continued racing over 5,000 in June. First he won against the GDR with 14:12.8 and then he beat Clarke again in the rain in Helsinki 13:40.4 to 13:41.4. A week later he ran 3:37.9 in Paris; this turned out to be his fastest 1,500 of the year. He double in the French championships, winning the 5,000 on the first day (13:57.2) and the 1,500 on the second (3:40.4). A final race in early September saw him winning a 5,000 in Stockholm with 14:18.4.

Mexico Olympics

|

|

Mexico 5,000 semi-final. Wadoux is running second on the inside. |

Wadoux finally decided on the 5,000, thereby avoiding Ryun, Tümmler and Norpoth. From today’s perspective this decision seems wrong, as the longer event would be much harder for him at altitude. However, he had dominated Gammoudi at Fort Romeu two months earlier, and he was confident he could win a 5,000 medal: “I saw myself on the podium. I knew Keino was too good for me. But behind him the places seemed open. I was convinced no one could get away from me. And in the sprint, except for Keino, I estimated I had a serious chance.” (MA)

And after the heats it looked like his confidence was justified. He was the fastest qualifier in winning the third heat in 14:19.8 ahead of the local favorite Juan Martinez and Harald Norpoth. The final started slowly with a 72 lap and sped up a little thanks to Ron Clarke. It was 4:32.7 after four laps, but then the pace slowed to 71.3. The whole field remained bunched. At nine laps (10:25) the pace was upped to a 65.8. Wadoux was still there, but before the end of the next lap he had dropped back from the lead group. In the last three laps he lost 15 seconds on the leaders and finished ninth (14:20.8), the same position he had finished four years earlier in the Tokyo 1,500. Ironically, the winner was the man he had defeated two months previously at altitude in Fort Romeu—Mohamed Gammoudi.

Later, Wadoux claimed that up to his run in the final he had not believed that the altitude would be a handicap. The expectant French public was disappointed. “It would have been better for me not to have gone at all,” he admitted to Marcel Hansenne. “But I realised that too late. Mexico didn’t suit me at all. I would have known for sure in 1967 when I went there for the pre-Olympic meet. Alas, I fell ill there [and didn’t race].” (MA) Hansenne then asked Wadoux how he could have done in the 1,500: “At best I think I could have finished fourth.” (MA)

After the Games, Wadoux publicly expressed concern that his Mexico efforts might have damaged his health permanently. He was reassured, however, by an electrocardiogram in November and began training. But he didn’t feel right: “I felt weak physically for a year. But I don’t think it was just the Mexico 5,000. It was also the effect of a large number of daily workouts.” (MA)

That partly explains why 1969 was a disappointing year. It was a tough winter for him emotionally, and a bad bout of flu didn’t help. Only in the spring did he regain his desire to train. His bad Mexican experience over 5,000 persuaded him to revert back to the 1,500. He still won the French 1,500 title with his season’s best 3:39.0, which ranked him fifth in the world. But he then got injured and had trouble getting ready for the Europeans in Athens. In fact he felt he was not ready to compete there, but Gaston Meyer and Marcel Hansenne talked him into going. With Tümmler and Norpoth absent, the race should have been easy pickings for a fit and confident Wadoux, but as it turned out, he was never really in the race, finishing 6th in 3:41.7 behind the winner John Whetton (3:39.4). If there was ever a major for his taking, this had been it.

Fulfillment

If 1969 was a low point in his career, the next year was the high point. He ran the second fastest 1,500 ever, coming close to Ryun’s world record, and he improved his 5,000 to 13:28.0, just missing Jazy’s French record of 13:27.6. As Robert Parienté put it, the Chrysalis became a butterfly. (La fabuleuse histoire de l’athlétisme, p. 376) This peak came after almost a decade of dedicated training and racing. As well as running fast times, Wadoux was also winning. He didn’t suffer a serious defeat until late in the season in the European Cup Final.

|

|

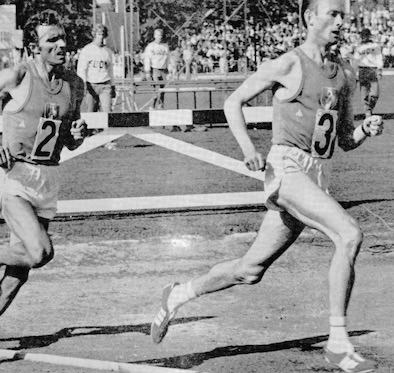

Wadoux's 3:34.0 European Record. Approaching 400 (56.7) in fourth, trails his three pacemakers. |

After an early 7:56.4 win over 3,000 and a stylish international win against Finland (13:46.8), he ran one of his finest races in a match against the USA on July 8. His main opponent was Frank Shorter, who had recently run a 27:24.0 Six Miles. Wadoux broke away with four laps to go and won by 14.4 seconds in a PB 13:28.0. He followed this with his fastest run to win a French 1,500 championship race (3:38.0). Five days later he went for a 1,500 record. It was a paced attempt; the London Times called it a “blatantly paced race.” (24 July 1970). After a fast start by the first rabbit Viaux, Wadoux passed 400 in 4th with 56.7. Toussaint now took over and passed 800 in 1:54.8 and 1,000 in 2:23.8. Blondel then took over, but only to the bell (2:38.5). Wadoux was now on his own and found enough to complete the last lap in 55.5. It was a European record of 3:34.0 and only 0.9 outside Ryun’s world record. “For sure, this will remain my best memory,” he explained. “I didn’t think I was capable of going under 3:35, and I was expecting a time of around 3:35.5.” (MA)

After defeating Brendan Foster in a 1,500 in Zurich (3:44.2), Wadoux made a record attempt at 5,000 in Oulu, Finland, but he got cramps after 2,000 (5:23) and dropped out. At the end of the season, he very nearly won the 1,500 in the European Cup Final in Stockholm. After laps of 62.0 and 63.8, he went to the lead at the bell and passed 1,200 in 3:02. He managed to hold the lead until the straight when Arese and Szordykowski drew level. In a desperate finish both of them just got by: 1. Arese 3:42.3; 2. Szordykowski 3:42.3; 3 Wadoux 3:42.6.

Bid for a European Title

Wadoux now looked ahead to the 1971 Europeans with renewed optimism. There was huge pressure from his country to perform well in a major games, and it looked like he now had the strength and the speed to win. After another winter’s training, he soon PB-ed over 3,000 with 7:52.0. And this was followed by a clear win over Emil Puttemans two weeks later at the end of June (13:37.0 to 13:40.0). This was an excellent first attempt of the season at the distance he would run in the Helsinki Europeans. Four days later he ran a 5,000 on the very track where the games would be held. This time Keino was in the field, but Wadoux took charge of the race, opening up a 10m gap on the back straight of the last lap and easing up into the tape with 13:30.4. With six weeks to go to the Championships, he was clearly the favorite for the European title.

In Helsinki Wadoux ran the fastest time in the heats (13:44.2). He was expecting Puttemans to stir up things in the final, but after Vaatainen’s dramatic 10,000 win in front of his home crowd, he wondered if there was any way to beat the Finn. True to his character, he took a very pragmatic approach for himself, especially after watching Bedford try to run away from the 10,000 field: “I’ve decided to follow the pace. It’s important not to forget that I’m not a natural 5,000 runner. If I’ve moved up to this distance, it’s because I lack the speed for the 1,500 sprint. I don’t think I will necessarily become the fastest finisher in the 5,000, but it’s worth a try.”

|

|

European 5,000 final: Vaatainen sprints to victory while Wadoux (142) holds off Norpoth for the silver medal. |

So Vaatainen was now the favorite despite his 13:43.2 PB being well below Norpoth’s 13:24.8 and Wadoux’s 13:28.0. The swashbuckling Finn claimed he had no tactical plans except to beat Norpoth and Wadoux. The race was disappointing. No one was prepared to take control of the race; it was as if everyone was waiting for Vaatainen to make his move. Wadoux finally burst ahead at the bell, but his move was not nearly decisive enough. Vaatainen was right on his heels round the back straight and with 300 to go moved up to pass Wadoux. There was some resistance for 20m but then Vaatainen was in front. However, the Finn did not open up a gap. Wadoux and Norpoth chased him closely, and with about 90m to go, it looked like any one of the three could win. Then Vaatainen found another gear and was comfortably ahead at the tape, running the last lap in 52.8 seconds. Meanwhile Norpoth moved up beside Wadoux. Wadoux held his form well, and Norpoth, after glancing across at his rival, fell back. Wadoux had the silver medal, but that wasn’t what he wanted. He had done everything right according to his pre-race plan but just seemed to lack the spark that Vaatainen had.

One More Chance?

Wadoux would be 30 at the time of the 1972 Munich Olympics. It would be his last chance to win a major gold medal. And he trained hard through the winter, competing regularly in cross-country meets and winning the French cross-country title from Tijou. But he then came down with a serious abdominal injury and had to abandon his career. We can only wonder how he would have run in the wonderful 5,000 race at Munich.

Conclusion

A common phenomenon in the sports media is to raise public expectations for success. National track champions are often expected to win internationally even though they will be competing against many other national champions in major games. Wadoux, especially after the successes of Jazy, was a victim of this phenomenon. He was expected to win at least one major title, and because he didn’t the French press often treated him unkindly. Even the respected Robert Parienté barely mentioned Wadoux’s wonderful 1971 European silver medal in his seminal history of athletics, except to say that Vaatainen’s last lap of 52.8 left him and Norpoth behind.

|

| Wadoux (68) races cross-country. |

Wadoux was a great runner. His 3:34.0 got him within less than a second of the current world record that had been set by the man many considered the greatest runner of all-time, Jim Ryun. And Ryun himself never won a major title either! True Wadoux didn’t have the competitive personality of a Zatopek or a Vaatainen or a Kuts, but he still performed well when it counted. Ron Clarke once made an interesting point about Wadoux’s character: “Jean Wadoux is a very good runner. Without the flair of Jazy, he may never win a big international race because he doesn't have the willingness to gamble.” (Ron Clarke Talks Track," John Hendershott, ed., 1972) But is it really necessary to gamble to win a major race?

Wadoux was serious by nature; in no way was he a gambler. He planned his career and his races minutely. And with that seriousness came the strength of character that Marcel Hansenne admired so much. Michel Jazy also respected Wadoux’s strength of character: “He is dedicated to track with a kind of glacial passion. His seriousness, his strength to lead a monastic life, will soon lead him to great records.” ( Mes victoires, mes défaites, ma vie, 1967, p. 24) So despite his admitted pre-race nervousness, it could be argued that Wadoux did indeed have the innate qualities to win a major race. Certainly he was unlucky with the circumstances surrounding most of the major meets he attended. And perhaps there was another reason why he didn’t win the one major race he might have one, the 1971 European 5,000. He always said that he lacked the finishing speed needed in major 1,500 races, and this lack of innate speed surely was the major cause of his loss to Vaatainen. If he had beaten the Finn, he would surely have been accorded a much higher place in the history of middle-distance running.

Note: Quotes from the French magazine Athlétisme are indicated with “MA.”

3 Comments