Bob Phillips Articles / Profile

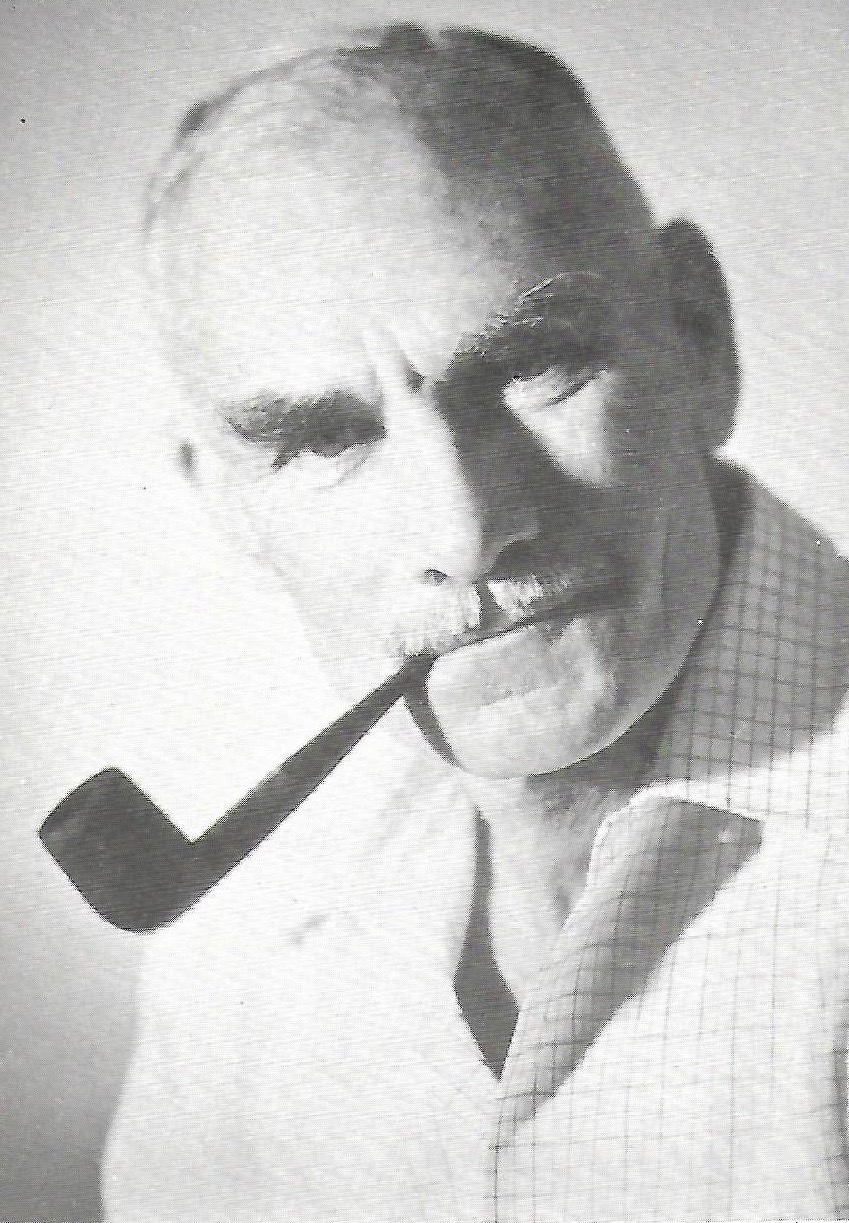

Noel Bretell: A Remarkable Poet-Athlete

By Bob Phillips

28th December 2018

Noel Brettell: Compassionate Observer of an “Arcadia of Jacaranda and Sunshine”

Who Ran with the Ghost of Tom Knocker

The life of a remarkable poet-athlete

One of the fervent admirers of the commitment to young athletes by Jack Price, the Olympic marathon runner of 1908, and particularly of his attention to the “the humblest rank and file”, went on to eminent achievement himself in the cause of the care and consideration of others. But this was all to happen in a very different area of activity, and even in a different continent. Noel Brettell, who claimed only to have had “modest success” as a runner, is celebrated to this day as one of the foremost poets to have emerged from Southern Africa.

Brettell was a member of an unbeaten Birmingham University team which won the British Universities’ Athletic Union cross-country title in 1930, and he then emigrated to Southern Rhodesia later the same year. There is no further record of him competing in his adopted land, and no doubt his teaching appointments in remote rural areas had a great deal to do with that. It seems perfectly feasible, though, that Rhodesia’s policy of racial segregation discouraged Brettell from maintaining his sporting interests; certainly, his writing displayed an acutely sensitive interest in the country and its people.

Rhodesia had gone through a series of political upheavals after the separate regions of Northern and Southern Rhodesia had been established at the end of the 19thCentury. They had then become a British protectorate and a self-governing colony respectively in 1923-24 and were brought together in 1953 as the Central African Federation of Rhodesia & Nyasaland. In 1964 Southern Rhodesia gained its independence as Zambia, and Nyasaland did so as Malawi. The following year Northern Rhodesia’s prime minister, Ian Smith, declared unilateral independence, which remained unrecognised by Britain and the United Nations and subject to severe economic sanctions until 1979. The next year the Republic of Zimbabwe came into being.

In Noel Brettell’s autobiography, “Side-gate & Stile”, written in 1970 but not published until 1981, when he was aged in his early 70s, he makes almost no direct reference to historical race relations. Early on in the book he writes: “I have always lived on the edges, seldom the sword edges of excitement, habitually the blurred edges of solitude, for most of my life on the tattered edge of the backveld in a remote and unimportant country”. Later he graphically illustrates his Rhodesian experience, “Come across an African village sequestered in a bowl of the hills, the brown cones of thatch rising from the brown earth as unconcernedly as a tree, children happy in the dust, women pounding meal, old men bent over intricate basketry, a cow-bell hesitant on the edge of an immense blue stillness – and it is easy to be bemused, easy to forget the tyranny of superstition, the anxiety of drought and hunger, the dirt, the malnutrition”.

A more pointed brief summary of the advantages – and disadvantages – of Rhodesian life during Brettell’s earlier years there is provided by a biography written in 2010 by Ray Haakonsen, “An Arrested Heart: An, ordinary man’s story of life in Rhodesia”. The author had been born in Southern Rhodesia in 1955, and he said of his parents’ arrival there from South Africa the previous year that “as long as you were hard-working, had some measure of vision and initiative, and – most importantly – you were white, the sky was the limit”.

Noel Harry Brettell was born in 1908 in the small town of Lye, which was then in Worcestershire and is now part of Dudley Metropolitan Borough in the West Midlands of England. Lye is only three miles or so from Halesowen, where the ex-Olympic marathon-runner and inspiring coach, Jack Price, lived, and Brettell commuted from home by train each day to university in the late 1920s and 1930. The name “Brettell”, which is of French Huguenot origin, is not uncommon in that region which in the 19thCentury had been an important iron-manufacturing centre.

Noel Brettell lived to the age of 83, dying in 1991, and so he experienced many of the radical changes in his adopted Rhodesian homeland at first-hand, and a detailed academic analysis of his written work was to describe it as “contemplating the life and landscape of Africa through the eyes of an Englishman in love with but not un-critical of its harsh contradictions”. It has also been said of him that “his honesty of contemplation, his poetic skill, his broad-mindedness, his attention to detail and his descriptive writing make Noel Brettell one of the finest poets that Southern Africa has produced”.

The foremost contemporary authority regarding this creative form is Professor Dan Wylie, of Rhodes University, in South Africa, and he has said for this article, “I would certainly agree with that assessment – though I suspect many would not. Brettell is a little old-fashioned for the modern taste in his forms – tight stanzas, strict rhyme schemes, sometimes a vocabulary a little archaic. But he was a close and compassionate observer of the critical world, even quite a tough one”.

A winning university cross-country team of 1930

Birmingham University’s cross-country win in 1930 was in the inaugural UAU event because this annual competition between universities – with the exception of Oxford and Cambridge – had been administered by the Inter-Varsity Athletics Board of England & Wales since its formation in 1919. Manchester University had won the IVAB cross-country event in 1929, with the University of Wales 2ndand Birmingham 3rd. The individual winner in 1930 was a Manchester University student and Old Harrovian, Ian Drew, who adventurously combined distance-running with pole-vaulting and harnessed his agility to a reasonably successful steeplechasing career, finishing in the first six in England’s AAA Championships every year from 1930 to 1934 inclusive and representing Great Britain against France in 1933. In the UAU race, which was held at Reading on 15 February, Birmingham won very easily from Manchester, 42 points to 88, with Brettell their 5thfinisher in 10thposition.

The team’s captain and outstanding runner was Joe Helps, who was to win the World Student Games 1500 metres in Darmstadt in August in a time of 4:01.7 which ranked 21stfastest in the World for the year. He also finished only a yard down on a future Olympic 1500 metres silver-medallist, Jerry Cornes, in a representative-match mile the same year and drew the plaudits of E.A. Montague, the athletics correspondent for the “Manchester Guardian”, who had himself been an Olympic steeplechaser.

Brettell’s only mention in his autobiography of his university’s UAU cross-country win is a very brief one, but there are a number of other references to his athletics pursuits, written in his characteristically impassioned and often florid style. He had attended King Edward VI Grammar School, in Stourbridge, only 1½ miles from home, which had been founded in 1430, and where Dr Samuel Johnson had been the most noted pupil. It was at that school that Brettell took up athletics at the age of 16, as he so vividly describes:

“I discovered by another chance that I could run. The school steeplechase at the end of the spring term was an event into which we were all press-ganged, most of us reluctantly, into teams of 12 from each house. So far I had ambled round the course, down a suburban lane and across the golf-links, without any enthusiasm or distinction. This year I was surprised to find myself running with no difficulty among the leaders. I have never, in all my subsequent races, enjoyed anything like that feeling of easy elation, so delighted in the glad April weather that I made no special effort to win. I astonished myself and everybody else by running into 2ndplace, a yard behind the winner, my own house captain. The next year, over a new five-mile course, I won by a quarter-of-a-mile. From then on, for the next five years, through my Sixth Form and university life, I became, with all the absurd and sublime seriousness of youth, the dedicated athlete, austere and sexless as a monk. No adolescent is happy until he finds a role to play, and I had mine now”.

Brettell then describes in detail the lasting impression in his university days that his relationship with Jack Price made on him. He said of Price that “like all good Black Country men he was given to truculent declaration” and quotes him as pronouncing, “The running-track is our only democratic institution – the only place where a chap from the steel-works and the noble Lord Burleigh can meet on an equal footing”. Brettell continues in tribute to Price, “When I got to know him, he was getting on for 50, and still, in an aura of local fable and hero-worship, a splendid runner, and training and exhorting some of the best runners of the day … He was a great lover of men, and I know that in the dark days of the depression he helped many a hopeless young man to self-respect by making a runner of him.

“Once or twice in my university vacations Jack invited me to join in his training runs. We would set out from his cottage on the outskirts of Halesowen, he and a few of the chosen, national and international runners among them, and myself a very nervous minnow among the tritons. In the winter twilight we would stride up the dark embowered tunnel of Ullmoor Lane, past the little Saxon church of St Kenelm, crouched among black yews on the lip of a high valley, and so, stumbling and plunging up the steep backwoods, out on to the shoulders of Clent, starlit, cold, mysterious. It was magnificent; the wild dark, the wind in the teeth, the hot smell of strenuous muscles, the beat of the pace. I would be thrilled to hear beside me the almost noiseless padding of the great man himself, lighter on his toes than we less than half his age”.

The blood singing through the veins like sap through a tree

Brettell enthuses of “that extraordinary exhilaration, mounting and continuing, that only a hard-trained athlete can know; the feeling not only of perfect health, the blood singing through the veins like sap through a tree, but of a spring finely and tightly up-coiled and vibrating impatiently to answer the needs of any effort”. Such gloriously descriptive writing about the joys of running makes the reader yearn for more, and there are other allusions – albeit tantalisingly brief – elsewhere in his book. At university, he says, “Thrice a week I would run over the heavy pastures sodden with the tributaries of the Bourn Brook through incredibly muddy farmyards, round Tom Knocker’s Spinney – Tom Knocker, a legendary poacher whose ghost we made the tutelary mascot of the University Harriers”. Brettell was fond of such obscure words as “embowered”, “up-coiled” and “tutelary”!

He clearly also ran some track races in those years, though no record remains of them, because he recalls, “Many of the fellow athletes with whom I shared idyllic hours of reminiscence and ambition, lounging on the running-track between furious bursts of training, came from beyond a fabled horizon I increasingly fancied I might stride over. There was Yoshida Tanida, a sprinter from Hong Kong; Carlos Braggio, champion pole vaulter, from the Argentine; and Joe Pitter, a mercurial Jamaican who won the inter-university long jump and javelin and who wielded his archaic weapon as if he were hunting his breakfast”. Of Tanida, who was clearly of Japanese origin, nothing more is known, but the names of both Braggio and Pitter are to be found in newspaper reports of athletics of that era. They were very able javelin-throwers by domestic standards, and Pitter won the UAU title in 1930 and had a personal best of at least 154ft 1in (46.96m) at a time when only a dozen British throwers had ever exceeded 156ft.

Brettell’s farewell to track athletics was a splendidly bucolic one, as he describes: “In the incredibly prolonged and holding summer of 1930, as charmed a summer as any of the mystical days of childhood, a disaster to the farmer and a benison to the idler, a dozen careless athletes sat cooling their heels in the Avon below Bidford. It was the halcyon hiatus between Finals and Degree Day, and we were on what we blithely called a running tour. We carried our camping paraphernalia in an old draper’s van we had borrowed, with a philosophical old bay horse to pull it. We had trotted behind the van through lanes of honeysuckle and elder from one village sports meeting to another, making a clean sweep of the long and middle distance events and having a cheerful go at the sprints. In the first lap of a mile race the spectators were mystified to see us begin to execute an odd crane-like ballet; we were negotiating the tapes of the hundred yards lanes which crossed the rustic track and which somebody had forgotten to remove”.

To a country of which he had hardly heard

Jobs were hard to find when Brettell graduated and he accepted a teaching post in Rhodesia, admitting that “coming to Rhodesia I did so with no ideals, to a job I was ready to dislike, to a profession I more than half despised, to a country I had hardly heard of and was not particularly interested in”. The British Empire, Brettell bemoaned, “was already a conscience-stricken embarrassment”. He returned to England a couple of years later and resignedly went back to Birmingham University to acquire a teaching diploma. There, he says, “I ran again for the university, and in a match against Reading I came in 1stof the field – for the only time, so far as I can remember”.

It was obviously an enchanting experience because he spoke of it as “a glorious run in the blue and silver winds of the Berkshire pastures”. Married soon afterwards, and teaching in a Sussex primary school, his athletics career seemed to have been brought to an end, and he then in 1934 accepted another offer from Rhodesia to teach the children of impoverished Dutch Boer settlers – and did so for the next 22 years until his retirement at the age of no more than 48, when he began to dedicate himself to his poetry.

During the course of a two-year headmastership, and by now long since enthused with educational fervour, Brettell had met “the most remarkable man ever to cross my path”. He was the reclusive and eccentric poet-missionary, Arthur Shearly Cripps (1869-1952). Brettell learned that Cripps, too, had been a three-miler while at Oxford University “when the record for the mile seemed fixed for ever at four minutes twelve seconds” – which places Cripps’s efforts precisely in the late 1880s, very shortly after Walter George had run his historic 4:12¾ which was to remain unsurpassed until 1915. Brettell remembered Cripps “being grimly amused when I told him that as late as 1929 I had been politely requested to leave the track because I was wearing a sleeveless vest”. It is the last reference to athletics that Brettell makes.

How Pirie and Halberg helped break the Rhodesia’s running colour bar

The standards of middle-distance and distance running in Rhodesia through the 1920s and 1930s were modest, with S.G. Turner the fastest miler at 4:34.4, but much the most notable athlete of that decade with a Rhodesian connection was the ebullient ultra-distance-runner, Arthur Newton, who habitually competed in a vest emblazoned “Rhodesia & Natal” across his chest.

In his eloquent biography (”Tea with Mr Newton”, Desert Island Books, 2009), Rob Hadgraft relates how Newton, who was English-born, in Weston-super-Mare, in Somerset, walked the hundreds of miles from his home in South Africa to Rhodesia to seek a new livelihood, arriving in August 1925, and then helped set up the Bulawayo Harriers club. Yet he only stayed in the country for two years before departing for England, paid for by public subscription in Bulawayo, to attack his own 100-mile record, and he never returned to Rhodesia. Even so, he was listed for many years afterwards as Rhodesian record-holder for 60 miles and 100 miles on the road. A co-founder with Newton of Bulawayo Harriers, R.P. (“Bobby”) Wilson, is said to have run a marathon in 2:33:50 in 1928, and if this is true then it was a time beaten that year by only the first two in the Olympic marathon and by Britain’s Sam Ferris.

Segregation remained in force on Rhodesian athletics tracks until the late 1950s, and when a US AAU team prefaced a tour of South Africa with a match against Rhodesia in Bulawayo on 2 September 1950 both the visitors and the hosts were exclusively white-skinned. The Americans won 13 of the 14 events, with six all-comers’ records, including 880 yards in 1:56.2, Even the list of Rhodesian national records at the beginning of 1958 consisted entirely of Anglo-Saxon names,

The the South African-born Terry Sullivan obliterated all memories of the indifferent miling of the 1930s by becoming the first runner from the African continent to break four minutes and was the bronze-medallist in the mile at the 1962 Commonwealth Games behind the formidable New Zealand duo of Peter Snell and John Davies. Sullivan, who had moved with his family from South Africa at the age of 10, ran 3:59.8 behind Herb Elliott in Dublin in September of 1960 – and, by a remarkable coincidence, the man who finished one place and one-tenth of a second behind Sullivan in that race was the one whose presence had been largely responsible two years before for breaking Rhodesia’s athletics colour bar – and maybe even entirely responsible.

Towards the end of 1958 Gordon Pirie had set off by ocean-liner from Britain with his sprinter wife, Shirley (née Hampton), for a seven-week tour of Southern Africa, where they were joined by the Empire Games three miles champion (and future Olympic 5000 metres champion), Murray Halberg, of New Zealand. but Pirie was by no means in the best of form, short of fitness after a month’s lay-off from training and suffering at high altitude and from the constant travelling.

He relates in his autobiography, “Running Wild”, published in 1961, that when he arrived in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (now Harare, in Zimbabwe), for a three miles race on 6 December he was greeted by a reception committee waving banners that read “Beware Muleya”. Pirie wrote, “Muleya was the local African champion who was to race with us in the athletics meeting. There had been a storm a week before when a Rhodesian Athletics Association official had ruled that Muleya could not run with us because he was black. But public opinion had forced the Association to over-rule the official. Murray and I had decided that if the ban had stayed we would race with Muleya at a meeting run by the Africans if necessary”.

Pirie’s view of the widespread local reaction to the situation is confirmed by a report from the local representative of the Reuter’s news agency in late November that “Southern Rhodesian newspapers, athletes and sports officials protested the Southern Rhodesia Amateur Athletic Association’s refusal to let Muleya run against Halberg and Pirie” and added that “seven founder-members of the Northern Rhodesia AAA sent a telegram to Home Affairs minister Sir Malcolm Barrow expressing ‘disgust and humiliation’ at the ruling”.

An historic win by the bare-footed local novice

As it happens, Halberg took part in the mile instead at the meeting and was beaten by Terry Sullivan in an altitude-affected 4:18.0, while Pirie succumbed to the local hero, Yotham Muleya, a 19-year-old apprentice motor-mechanic at a technical college, who won by 200 yards in 14:48.3, “cheered to the echo by a 4,000 crowd”, according to an eye-witness report. Muleya, whose first name is also sometimes spelt “Yotam”, had a previous best for three miles of 14:57.0 the month before, set within an hour of also winning a mile race, though the Rhodesian record was still credited to a white athlete, Frank Pearce, at 14:59.9, in Bulawayo the previous March. Pearce and his identical twin brother, Keith, had also shared a national six miles record of 32:46.0 in Bulawayo in February. To give the brothers their due, they were to achieve very capable results in future years after they had emigrated to other countries..

Pirie doesn’t say a great deal about his race against Muleya – understandably, perhaps – but enthuses about the winner: “Muleya was a quiet, charming fellow and an excellent runner. I met him a couple of days before the meeting and advised him on points about the three-mile race in which we were both to appear. It was I who suggested he should race with bare feet. He hadn’t worn spikes more than once, and they would have been a disadvantage to him. Muleya not only won the race but set up a Rhodesian record, and the crowd of whites and blacks ran across the track in their enthusiasm as he won, and I had to make my way through them to the finish”. In his excellent biography of Pirie (“The Impossible Hero”, published by Corsica Press in 1999), Dick Booth says that Pirie was still declared the official winner but handed his prize over to Muleya.

Muleya came from a family of achievers in a rural village because both his elder brothers qualified as teachers, and the idea of running for fun – as Muleya did for 10 miles or so early each morning – was one that was incomprehensible to his neighbours. In a book entitled “Zambia’s Sporting Score”, first published in Zambia in 1990 and re-issued in the USA in 2011, Moses Sayela Walubita explains why: “In traditional village life there was no aimless sport. All sport was practical and purposeful. Young boys were involved in spear-throwing competitions for both distance and accuracy, in wrestling for body-building and stamina, and in boxing. All sport was to prepare the child for self-defence or for preparation into adulthood”. When photographs appeared in the local newspaper of Muleya’s victory over Pirie, Walubita says poignantly: “He was shown running ahead of a white man. He was not running away”.

“What fantastic champions these fellows will be one day!”

Pirie also paid a sightseeing visit to Northern Rhodesia, and though there was no race for him there he noted, “Fifty Africans turned up to train with us in Lusaka. Few of them had ever consciously taken part in athletics before. Nevertheless, they ran for an hour or more without complaint. What fantastic champions these fellows will be one day”. Prophetic words from Pirie, and within two years a black Southern Rhodesian, Cyprian Tseriwa, had run a highly respectable 14:28.7 for 5000 metres and 30:47.8 for 10,000 metres. The Rhodesia & Nyasaland championships had been racially-integrated for the first time in 1959, and the next year Tseriwa won the three miles and six miles and became the first non-white athlete to represent Rhodesia at the Olympic Games. He had been a school-teacher but was appointed sports instructor with a major mining company in recognition of his Olympic appearance. .A successor as national record-holder (13:48.8 for three miles, 30:00.8 for 10,000 metres), Bernard Dzoma, who ran as much as 18 miles a day in training under the direction of an Australian-born coach, John Cheffers, was not so fortunate. Though selected for the 1968 and 1972 Olympics, he and his team-mates were banned on both occasions because of their country’s unsanctioned declaration of independence from Britain.

It is worth noting that despite the sensational victory for Ethiopia of Abebe Bikila in the 1960 Olympic marathon, there had still been no impact by his fellow-countrymen in track events, and very little by Kenyans – Kipchoge Keino ran a 4:07.8 mile that year, ranking 67thin the World, and Nyandika Maiyoro, who had first emerged in 1954, 13:44.2 for three miles, worth about 75thranking at 5000 metres – and so the performances of the black Rhodesians, Muleya and then Tseriwa, seemed particularly significant as signs of an African advance.

In the 1961 Rhodesian national championships black athletes took the first three places at 880 yards, three miles and six miles (Tseriwa 2ndand 1stin the latter two events), plus 2ndand 3rdplaces to Terry Sullivan in the mile and 2ndin all three hurdles races. No doubt part of the reason for such a level of success had been Rhodesia’s appointment of Jim Alford as national coach. Alford, who had won the Empire Games mile title in 1938, had been Welsh national coach for 10 years before moving to Rhodesia, and he was to write in “Athletics Weekly” about his change of circumstances in terms which reflected shamefully on British officialdom: “I am certainly glad to say that I am now paid a salary that is much higher than many influential AAA and BAAB officials think any National Coach is worth. I also enjoy more respect, co-operation and goodwill, as an experienced professional coach, than I ever did with the AAA. I was thoroughly disillusioned by the lack of confidence, and indeed the antagonism, shown by several of the most influential officials both of the AAA and the British Amateur Athletic Board”.

Even before taking up his new appointment which continued until 1962, Alford had started advising Yotham Muleya by post, and this had come about because Richard Hall, a senior manager in the Northern Rhodesian government information office (and a former 1:52.5 half-miler who had run for Oxford University in the 1959 Inter-Varsity match), had written to Phil Pilley, the editor of the respected UK monthly magazine, “World Sports”, who had been campaigning vigorously about the detrimental effects of racial segregation in sport. Hall said that “Muleya looks to me as though he has real talent if it could be brought out, but there is no expert coach here who can help him much”. Alford had then been contacted by “World Sports” via the AAA national coach, Geoff Dyson.

Even so, neither Alford, nor Pirie, nor anyone else, for that matter, could possibly have envisaged that in the fullness of time the 10,000 metres records for Zambia and Zimbabwe (as Northern and Southern Rhodesia were to become) would be, respectively, 28:00.33 and 27:57.34. Yotham Muleya did not figure again in this progress because, sadly, he lived only another year after his defeat of Pirie, dying as a result of a car collision in December 1959 near the town of Mount Pleasant, Michigan. Muleya and a white Rhodesian, John Winter, who had set a national 440 yards record of 48.8 in 1957, had been awarded US State Department three-month scholarships to Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant and were on their way to a cross-country race when the accident happened. Muleya remains an iconic figure in Zambia, as there is a road, a school and a sports-ground in Lusaka which are all named after him.

There is no means of telling if Noel Brettell was fully appreciative of such particular social advances in athletics in his Rhodesian lifetime, but he surely would have heard of Muleya’s historic win and been gladdened at heart by it. Certainly in literary terms he expressed his views unequivocally. In a letter to friends he wrote of the poetry which had been produced by his Rhodesian contemporaries that “it is only about 1961 that you get any hint that we haven’t been living in an arcadia of jacaranda and sunshine”. A journalist for the “Rhodesia Herald”, Neil Tully, was to state in 1972: “Noel Brettell does not slide away from awkward problems. He meets them head on”.

Maybe some of that determined spirit encouraged by Jack Price back in Halesowen and over the neighbouring hills “with the wind in the teeth” in the 1920s stayed with Noel Brettell all his life.

Helter-skelter with the jigging mob!

A poetic postscript

“Vox Populi” by Noel Brettell

The night is full of noises: shrill

With prophecy or dull with doom,

The ghostly tongues of Babel fill

The corners of the quiet room.

The night is restless: turn the knob

From news review to song request,

Symposium grave and jigging mob

From Hilversum to Budapest.

The roar of crowds at the ring-side

That breaks like surf on reef and skerry,

And tossing down the frothy tide

The helter-skelter commentary.

The rain is drumming on the roof

And mutes the feeble spurt of morse,

The lonely voice of ships, aloof

Antennae peering out the course.

The wind is rising: change the tune

From metre band to metre band,

From acid quip to oily croon –

Till, with a chance turn of the hand,

The tail-end of a piece of Brahms

Mounts the last stair and sudden stops,

To strand us with uplifted palms

Dumbfounded on the pinnacle tops.

This poem is an extract from ”Side-gate & Stile; An essay in autobiography”, by N.H. Brettell, Books of Zimbabwe Publishing Company, Bulawayo, 1981.

Thanks to Professor Dan Wylie for his responses. There is a detailed and highly informative study entitled “Sport and Racial Discrimination in Colonial Zimbabwe” which can be found on the internet at www.rhodesiaservices.org, though the author’s name is not given. Thanks also to Rob Hadgraft for further information regarding Arthur Newton.

Leave a Comment