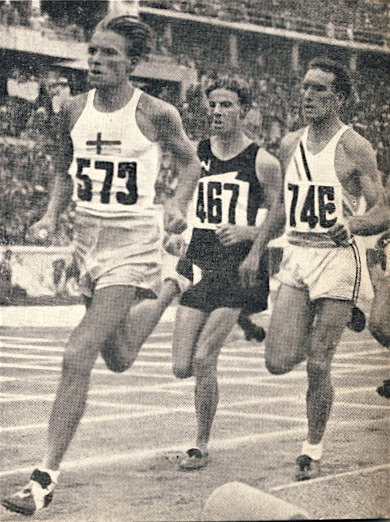

Gaston Reiff v Emil Zatopek 1948 Olympic 5,000 FinalGreat Races #6After his surprising win over WR holder Heino in the 10,000, Emil Zatopek lined up for the 5,000 as the crowd favorite. But there were two concerns about his chances: first, whether he had recovered from the earlier race, especially since he had put in a needless sprint at the end; and second whether his pointless race with Sweden’s Ahlden for first place in the 5,000 heats would take the edge off him. Others pointed out that the five-and-ten double hadn’t been achieved since Kolehmainen did “the impossible” 36 years earlier. Zatopek himself, after losing to Ahlden in the heats, thought that the Swede might just get the better of him in the final.

The three favorites for this Olympic final were all reaching the climax of their careers. Luigi Beccali (29) of Italy had broken the WR for 1500 in 1933; he was also the reigning Olympic and European 1,500 champion. American Glenn Cunningham (25) was the current WR holder for the Mile, and he had been fourth in the 1932 Olympic 1,500 final. New Zealander Jack Lovelock (26) had set a Mile WR in 1933 but had not subsequently run as well. Still, a recent 3:01 time-trial over 1,200 showed he was back to his best form. These three great runners knew each other well from previous encounters on the track. Beccali had the best record, having beaten Cunningham once and Lovelock twice. Cunningham had beaten both men once, while Lovelock had beaten Cunningham three times. All three were known for great finishing kicks, so it promised to be a tactical race.

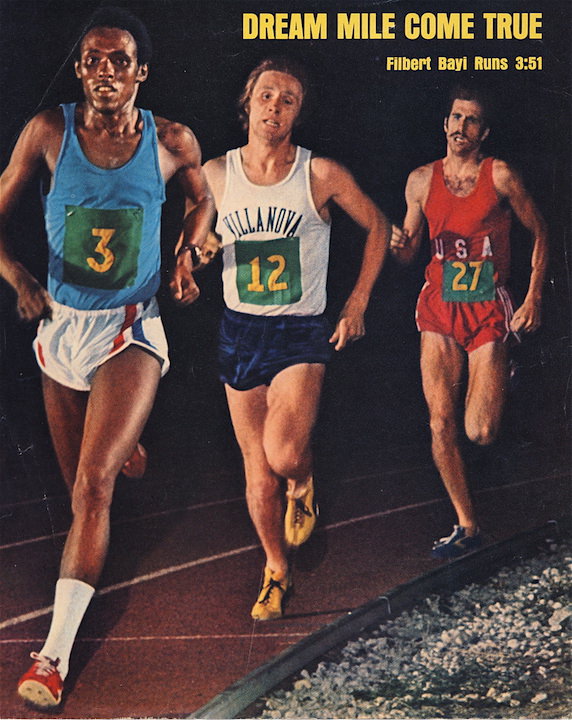

Bayi v Liquori v Coghlan1975 Dream MileInternational Freedom GamesKingston, Jamaica. May 17, 1975Great Races #23 Kingston, the venue for the 1975 Freedom Games, produced a capacity 36,000 crowd to see not only a version of the Dream Mile but also a sprint contest between Steve Williams and Houston McTear. While the sprint races were predominantly an American affair, the Dream Mile had a far greater international flavour. True, there were four Americans in the field, but there were also an African, a Brit, an Irishman and a Jamaican. It was an impressive field.

Halberg v Grodotzki v Zimny1960 Olympic Games 5,000 RomeGreat Races #14 If Elliott’s victory in the 1,500 was the most dominant track performance of the Rome Olympics, Murray Halberg’s was the most courageous. To inject a 61.1 tenth lap in a 5,000 meant that he had exposed himself completely. He had planned with his coach Arthur Lydiard to carry out this daring strategy: “Towards the end of the race he would launch himself into a breakneck speed for a whole lap. He would hold this speed for as long as possible. It would gradually and inevitably fade until he and the whole field were drained of all their speed. They would then have to run the last lap in a state of utter exhaustion, on rubber legs, gasping for breath.” (Norman Harris, Lap of Honour, p. 111) Although certainly not the most talented runner in the field, Halberg was the most determined to win. And he did.

GREAT RACES #20 30,000 Crystal Palace, September 5, 1970 A lot of international runners were still in top form after the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, and they were looking for races. On September 5, Coca Cola sponsored an international meeting at the relatively new Crystal Palace Stadium, which boasted a tartan track. One of the races set up for the meet was an unusual one: 30,000 meters. And the target was Jim Hogan’s WR of 1:32:25.4. An impressive field of in-form distance runners was assembled:

Jazy v Norpoth v Schul v Dellinger5,000 1964 OLYMPIC GAMES, TOKYOGreat Races #16 Several runners lined up with realistic hopes of gold. Frenchman Michel Jazy, moving up from 1,500, hoped to improve on his silver medal in Rome. He clearly had the finish to win a slow race, but he had not proven himself in a fast race over this distance, his best being 13:50. Though not as fast a finisher, Ron Clarke of Australia was looking to make up for the disappointment over 10,000 four days earlier. With a three-mile time equivalent to about 13:39, he had to be considered a gold prospect.

Olympic 5,000, Stockholm 1912Great Races #2 This great race was contested by the two leading runners of the time; both were considered almost unbeatable. Their superiority over all other runners was huge. And in the heat of this race the WR was decimated by an unbelievable margin.Frenchman Jean Bouin, 23, looked more like a boxer than a runner. He was thought to be overweight but said, “I haven’t got an ounce more fat to lose.” Bouin relied mainly on enthusiasm and was not considered hugely talented. But he was tough, making his name in cross-country. He had been national champion since 1909, and after running second in the 1909 International CC race, was the international champion for the next two years.

Keino v Ryun v Tummler v Norpoth v Whetton 1,500 Olympic FinalOctober 20, 1968, Mexico CityGreat Races # 21 Pre-Race This Olympic final saw a confrontation between the two fastest milers ever. And both had question marks against their current form. WR-holder Jim Ryun of the USA had recently battled with two injuries and mono. He had returned to form in the nick of time, qualifying comfortably with a 1,500 time of 3:49.0 (1:50.8 last 800). Kenyan Kip Keino had been suffering from stomach pains (later diagnosed as gall-bladder inflammation) while racing in Europe. And in the 10,000 final that preceded this race he had collapsed from the pain. Still, he was on the start line—against his doctor’s orders. Another question mark against Keino was that he had already run two finals (5,000 and 10,000) as well as three prelims. This race would be a hard test of his ability to recover.

Kemper v Boulter v Tümmler v Carter v Matuschewski Great Races #25 European 800 September 4, 1966 Budapest In the mid-1960s, the retirement of Peter Snell left a void in the 800. He had dominated the event for four years--from his Olympic win in 1960 to a repeat win in 1964. However that void was soon filled. In 1965 there were only five runners under 1:47; in 1966 there were eighteen. One race that exemplified this change was the Euro 800 in 1966, where the sixth runner ran 1:47.0. The 1966 European final for the 800 was loaded with talent. Foremost was West German Franz-Josef Kemper (20), who had just broken the European record with 1:44.9, only 0.6 off Peter Snell’s WR. Many considered him the odds-on favorite—the fastest man and the man in form. His team-mate Bodo Tummler (23), though not so fast over 800, could not be discounted after his impressive win in the Euro 1,500 a few days before. In this 1,500 race Tummler had soundly defeated the great Michel Jazy with an impressive 52.7 for the last 400—almost the exact speed of Kemper’s 1:45.9 European 800 record. Additionally Tummler had already show great tactical ability.

Mills v Clarke v GammoudiGreat Races #1610,000, Tokyo Olympic Games, 1964 This race was billed by Track & Field News as “the greatest 10,00 meters of all time.” There was a large field of 38 starters. Even more had entered, and there was a strong lobby to schedule heats. As it turned out, the large field did affect the race in the last lap as the leaders had to dodge in and out of the 12 lapped runners. Clarke compared his last lap to “a dash for a train in a peak-hour crowd.” (Ron Clarke, The Unforgiving Minute, p. 19)