Bob Phillips Articles / Profile

James Kibblewhite: Great All-Rounder of the Victorian Age

By Bob Phillips

18th May 2017

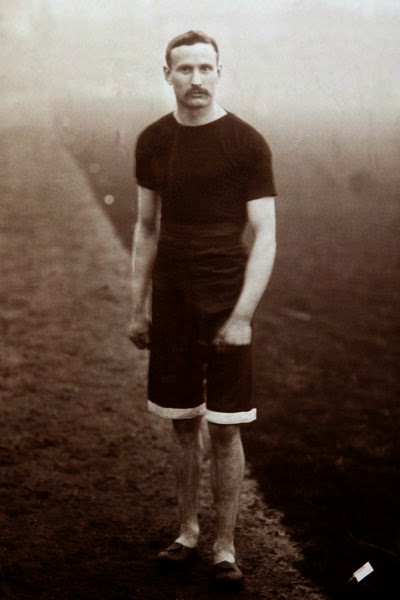

James Kibblewhite: Great All-Rounder of the Victorian Age

The “cudgel-maker” of the 1890s: head-to-head from 880 yards to 10 miles

|

Just imagine some enterprising promoter getting Wayde van Niekerk and Mo Farah together for a one-to-one speed-v-stamina show-down at 1000 metres ! It would no doubt cost a packet of money, and maybe even then not enough to tempt the pair of them away from the relentless Grand Prix round where running yet another 400 metres or 5000 metres rewards them so lavishly. Back in the 1890s there were no such inhibitions among the leading athletes about switching distances, and even though the financial return when Edgar Bredin lined up against James Kibblewhite was not quite on the same level as in 2017 it was still a highly attractive proposition. It’s reliably reckoned that the leading amateurs of the 1890s were regularly being paid £5 a meeting in appearance money until the AAA finally clamped down and suspended for life several of the “super-stars” of that era. A fiver in 1892 is worth some 700 times more in today’s values.

Accepting that athletes’ incomes were still somewhat less elevated at the end of the 19th Century, the fact is that both Bredin and Kibblewhite had something else to do between races other than test out the latest batch of free deliveries from a shoe-sponsor or answer the banal questions of TV interviewers. Bredin was born in Gibraltar in 1868 and led a varied and often highly adventurous life after a spell as a tea-planter in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and then as a fruit-farmer, and in 1897 he left the amateur athletics ranks, going on to win three titles in the events for professionals held at the 1900 Olympic Games. In his first two years as a paid athlete he won £510 alone from five challenge races, again amounting to some 700-fold more in 2017 income value ! He married, and the couple had four children between 1896 and 1902 but divorced in 1908. By then he was describing himself as a writer and a member of the theatrical profession, and he emigrated to Canada, where he joined the mounted police. He died in 1939.

James Kibblewhite – known familiarly as “Jimmy” – was by trade a machinist at the Great Western Railway depot, which employed three-quarters of the entire work-force of the 45,000 population of Swindon, in Wiltshire. His weekly wage there would certainly have been considerably less than half of what he earned in prizes for running round a track, but presumably he was wise enough to ensure that he had a steady job to sustain him beyond his sporting prime. Born in 1866 in the village of Purton, four miles (six kilometres) north-west of Swindon, his unusual surname derived from the Old English words, “cybbel whyta”, meaning “cudgel-maker” or “club-maker” – the implements being used as weapons. Judging by his occupation at the GWR depot, manual dexterity had remained a family trait through the centuries.

Kibblewhite is well remembered in his native county as there is a collection of his trophies, medals and newspaper cuttings in the Purton museum, and also in the village there is a “Kibblewhite Room” at The Pear Tree Hotel and a “Kibblewhite Close”. An article about him was published in the “Swindon Heritage” magazine in 2013. There are also in existence records of other 19th Century families named Kibblewhite from the same area who may well have been related. Richard Kibblewhite, born in in 1811 in the village of Broad Blunsdon, less than six miles from Purton, emigrated to New Zealand in 1841 with his wife and their 10-week-old son, also named James.

.

In his centenary history of the Amateur Athletic Association, published in 1980, Peter Lovesey neatly summarised the prevailing financial circumstances in athletics during the 1890s: “Most of the abuses in athletics in the first 20 years of the AAA were attributed to betting, but the biggest scandal of all, in 1896, arose from payments of money by clubs to athletes as inducements to appear at their meetings and boost attendances”. The AAA suspended for life five of the best athletes in Britain – sprinters Charles Bradley and Alf Downer and distance-runners Fred Bacon, George Crossland and Harry Watkins – though neither Bredin nor Kibblewhite were implicated in the investigations. In an immensely informative history, “Powderhall and Pedestrianism”, published in 1943, David A. Jamieson pointed out in relation to Bredin turning professional that “it must be recorded that his transition to the paid ranks was the result of a deliberately considered review of his private position … his bona fides as an amateur were never once challenged by the AAA, and his action created as much astonishment as, say, the secession of any eminent theologian from one faith to another would have done”.

Bredin and Kibblewhite were both World record-holders, at 440 yards and three miles respectively. Bredin also won five AAA titles, of which two were at the 440 and three at 880 yards, and Kibblewhite six, including three at one mile, two at four miles and one at 10 miles. So it was truly a clash of contrasting champions at 1000 yards on the afternoon of Saturday 20 August 1892 at the annual Reading Sports, in Berkshire. Bredin’s winning time was nothing at all exceptional, more than 10 seconds slower than the fastest ever of 2:13.0 set by the extraordinarily lanky American, Lon Myers (another supremely versatile runner of that generation), the year before, but the winning margin was desperately tight, and the several thousand spectators no doubt went home to their supper highly pleased with the entertainment – and blissfully unaware, of course, that anyone would be the least bit interested 125 years later.

In 1902 Bredin, by now pursuing his writing career, published a book entitled “Running and Training”, and in this he gave an entertaining account of the Reading race: “I for the first time met Kibblewhite (the winner of numerous championships on the flat and across country, who could run a half-mile inside two minutes and 10 miles inside 52), and beat him by half-a-yard, which was then considered a somewhat lucky win on my part. One sporting paper concluded by the following noble words – ‘The enthusiasm that prevailed whilst the race was in progress was almost indescribable. Kibblewhite and Bredin were the popular idols of the hour’. I like that term ‘popular idols of the hour’, but – to slightly misquote the poet – ‘Words, idle words, I know not what they mean’ ”. Bredin’s literary flourish is probably a reference to Walter Savage Landor (1776-1864).

The “very large company” at Kennington Oval go away happy

Kibblewhite and Bredin met again for another invitation 1000 yards a month later at the South London Harriers Autumn Meeting at the Kennington Oval cricket ground, and on this occasion Bredin was much more easily the victor, by six yards after Kibblewhite had made all the pace until 60 yards from the end. The winner ran only a couple of seconds faster than at Reading, and maybe Kibblewhite, though famed for his finishing powers, didn’t quite have the speed that day to run Bredin off his legs,. Even so, “The Times” described it as “a capital contest” and added that “the very large company which assembled must have been well satisfied”. We can assume that Bredin and Kibblewhite were well satisfied, too, with the prizes presented to them for their efforts.

Bredin certainly remembered the race with sufficient feeling to write about it passionately in detail a decade later: “Kibblewhite, on trotting first to the mark, was greeted with considerable applause. My appearance a little later was heralded with no such sign of approval from the spectators, and the Swindon runner, whilst the start was being photographed, observed, ‘You mustn’t mind them cheering me a bit and leaving you out. You see, I’ve run here so often’. Never did I experience less satisfaction in defeating a good man than I did on that occasion”.

Kibblewhite’s county of birth, in the south-west of England, is better known for its Stonehenge circle and other ancient monuments and for its Salisbury Plain army training-grounds, rather than for the athletes it has produced, and when I carried out a survey a couple of years ago of the origins of the 586 Great Britain international track & field representatives between 1896 and 1939 I did not find a single one who was born in Wiltshire. Nevertheless, Kibblewhite was inspired almost on his own door-step in his early running career by one of the greatest of all middle-distance and long-distance runners. Walter George was eight years Kibblewhite’s senior, born in 1858 in the small town of Calne, which was to the south of Swindon and only 14 miles away from Purton. It was in the same year of 1884 as George set the last of his three amateur mile records, 4:18 2/5, that Kibblewhite took up athletics, joining Swindon Harriers at the age of 18.

His name crops up on a number of occasions in an excellent 80-page biography of Sydney Thomas, which was written and published by Warren Roe in 2013. Thomas (whose first name was commonly shortened to “Sid”, not “Syd”, as one might have supposed) worked in the family firm of dyers and chemical cleaners and was Kibblewhite’s successor as three-mile record-holder. By way of introduction to Thomas’s competitive career, the author helpfully describes the appeal of the sport to young men of such modest social standing as these two were: “Amateur sport for those not at university or public school had been in existence for a relatively short time, and for the great majority of runners not at university the only way to enjoy the sport was to join the local harrier club”. Training and racing would usually occupy just a couple of days a week, though Kibblewhite in all probability did more than most, as he was credited later in his career for his devotion to “persistent practice”. Thomas was a member of the Surrey-based Ranelagh Harriers, which had been one of the founder-members of the National Cross Country Union in 1883.

Within three years of Kibblewhite’s debut he was making his mark nationally. On 2 April 1887 he won a four miles race at the London AC First Spring Meeting at Stamford Bridge in 20:34, just half-a-yard ahead of William Coad, of South London Harriers. There were 46 starters from 13 different clubs and the team award went to Birchfield Harriers. Walter George held the current record of 19:39 4/5, set in the same stadium three years before, and so this was a highly commendable performance by a still relatively inexperienced runner such as Kibblewhite was. During the winter Coad had beaten Kibblewhite decisively at the Southern Championships cross-country event which had been a typically demanding race of that era, contested at Surrey’s Kempton Park, “twice round the racecourse, through one of the gates, over the surrounding countryside”. Coad had finished 300 yards ahead of Kibblewhite in 1 hour 4 minutes 35 seconds, with Sid Thomas back in 7th place.

Rail travel was easy in Victorian time and enjoyed by many hundreds of thousands of passengers of every social status each year. The London & North Western Railway company had been operating a service to Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool since 1838, and Queen Victoria took an away-day trip with her children from Windsor Castle to Birmingham on Wednesday 24 March 1887, leaving home at 10.30 a.m. and arriving at Small Heath Station at 1.15 p.m. No doubt Her Majesty had the benefit of all the signals along the way being set at green. Even so, it’s odd that there was a curiously marked reluctance by London-based cross-country clubs to make the same sort of journey for the annual National Championships. Merely six teams and 53 runners had taken part in the National at Four Oaks Park, Sutton Coldfield, near Birmingham, on the opening Saturday of that month, and the only entrants from outside the Midlands were from South London Harriers, Bristol AC and Bristol Harriers.

The highlight of the English track & field season, the AAA Championships, were held at Stourbridge, in Worcestershire, 80 miles north of Kibblewhite’s home village, on 2 July, and he gave one of the very finest runners of the day, Francis Cross, of Oxford University, a heated contest in the mile. Cross won by two yards in 4:25 2/5, and Kibblewhite’s showing that day would surely have attracted much more attention had it been in London. Cross also won the 880 yards and the next year was to achieve the fastest ever time of 1:54 3/5. Kibblewhite was reported as having run an estimated 4:20.0 in a handicap mile at Pershore, also in Worcestershire, in August of 1887. The next year, the AAA laudably again took their Championships out of the capital, to Crewe, and were rewarded with an attendance of 10,000 as one of the group of visiting Americans, Tommy Conneff, won a tactical mile in outside 4:30 from William Pollock-Hill, of Oxford University, and Kibblewhite.

A move to a London club for better competition … and other incentives ?

By 1889 Kibblewhite had left Swindon Harriers and joined the North London club, Spartan Harriers, which was regarded as one of the top seven in the capital, with a total membership of 1500 or so between the lot of them. The higher level of competition offered must have been a good reason for the change, though it can be assumed that there were other incentives, too. There is no obvious evidence that Kibblewhite changed home or job to the London area, but if not he surely didn’t pay his own expenses for his future regular visits there. Maybe, as a railwayman, he received a free travel pass !

Even when the 1889 National was brought to Kempton Park on 2 March, there was still no enthusiasm for it among London clubs, though the Southern had been held at the same venue the month before and Spartan Harriers – apparently without Kibblewhite – had won the team title and Sid Thomas had been the first man home. Neither Spartan nor South London Harriers took part in the National, and so three clubs who were prepared to undertake much longer train travel south were rewarded instead as Salford Harries won from Birchfield Harriers and Leeds Harehills Harriers. Sid Thomas was 2nd to Salford’s defending champion, Edward Parry.

It’s not immediately obvious as to why the National Championships were spurned at a time when the sport was growing so rapidly in popularity, and it had not always been so because there were 105 competitors when the race was held in 1881. It may have simply been a matter of clubs only supporting the event if they thought they had a good chance of individual or team success, though another more sinister answer is ready to hand.

Montague Shearman’s iconic history, “Athletics and Football”, first published by the Badminton Library in London in 1887, contained a chapter on cross-country running by Walter Rye, one of the pioneering influential figures in athletics since the 1860s, who complained bitterly of the way in which the National had been organised from 1883 onwards: “The affair has degenerated into a gate-money meeting held on enclosed grounds, and forms the medium of heavy betting and little sport, the change having been effected chiefly by the country-men and their allies, ostensibly because they wanted ‘a rougher, more open country’, but really because they wanted to take the management of the meeting from its original promoters, who would have nothing to do with gate and betting”.

The aftermath of the 1886 National had been notoriously contentious as the bookmakers’ favourite for the title was the Birchfield Harrier, William Snook, of whom Walter George had said admiringly, ‘He worried the life out of me in scores of races’, but Snook had been beaten into 2nd place. After protracted deliberations, he was suspended by the authorities for life for “roping”, which was the term for deliberately allowing an opponent to win – in this instance J.E. Hickman, from the Coventry-based club, Godiva Harriers. In his splendidly entertaining 2008 biography of Snook, Harry Andrews notes that the pre-race betting was 6-to-4 against Snook and 4-to-1 on for Hickman, and that in an obituary of Snook after his death in 1916 it was said that “many people thought the he had achieved something in the nature of a feat in managing to retain his amateur status until 1886”.

So Walter Rye had some strong evidence to support his case. It should be noted, though, that he was a die-hard advocate of socially distinctive amateurism. He was a solicitor by profession who had publicly stated his belief that athletics clubs should not “admit as members men who are not gentlemen by position or education” and had referred ungraciously to the 1880 National team winners, Birchfield Harriers, as “very well trained, if rough” (did he mean elbows or manners, or both ?). Rye also wrote a weekly column for the “Sporting Gazette” publication and this was to be pointedly described by Peter Lovesey in his AAA centenary history: “His blend of bigotry and wit was entertaining to read if you were not in the firing-line”. Rye further said of the National, “Some day, when the loathsomeness of ‘roping’ and betting has disgusted the better class of runners, a championship in which gentlemen can take part without loss of self-respect will probably again be instituted on the old lines”.

In defence of the snobbish Mr Rye, it should be pointed out that the stalwart middle-class and lower-class club cross-country runners who were not privileged university undergraduates or civil servants owed him a great deal. Peter Lovesey concisely summarised the formative years of this branch of the sport in his AAA centenary history when he wrote, “In the 1820s foot steeple-chasing, usually between local landmarks, was staged in the Scottish Lowlands and soon spread to the English North and Midlands. By 1834 the sport was known in the public schools, with hare and hounds, a form of paper-chase, adding an extra dimension. The credit for initiating cross-country at club level is given to Walter Rye … he organised a run in 1867 for Thames Rowing Club which led, the following year, to the founding of Thames Hare and Hounds”.

Kibblewhite, untainted by any accusations of deceit, was a mature runner by 1889, and he and Thomas had a stirring battle in the AAA 10 miles track championship at London’s Stamford Bridge on 6 April. Thomas eventually won in 51:31 2/5, which was impressively close to Walter George’s 1884 record of 51:20.0, and Kibblewhite was 2nd in 51:40 3/5, with the 3rd-placd runner almost three minutes behind. In his 1902 book Edgar Bredin gives a wonderfully detailed account of the race. Apparently, Thomas had been advised by his coach, Jack White, who had been the greatest distance-runner of the 1860s, to set the pace and try to wear Kibblewhite down, but then the latter had gone to the front and deliberately slowed. On the last lap Thomas “ran on, expecting every moment to be passed by the faster finisher”, only for Bredin to recall: “However, there is a limit to all things, and a time when even the best runner finds his legs refuse to be lifted from the ground, which fact was forced upon Kibblewhite when he was only some 50 yards from the tape”.

Stamford Bridge – which is now the home of Chelsea Football Club – had been opened in 1877 as the headquarters of the country’s oldest athletics club, London AC, founded in 1863, and it became the major national venue for meetings. Kibblewhite would race there on dozens of occasions during his competitive career, and the track would remain in place even after the new owners founded Chelsea FC there in 1905. The AAA Championships would be held at the stadium on nine occasions from 1886 to 1906 and then every year, except during World War I, from 1909 to 1931. On the day that the track opened Fred Elborough had set a World best performance for 600 yards, and some 40 other fastest-ever times from 100 yards to 30,000 metres were established on the same cinders in the years before records came to be officially recognised in 1914. The AAA Championships were open to competitors of any nationality and were regarded – at least by the organisers – as a “World Championships”, with the most notable official World record achieved throughout its tenure of Stamford Bridge being the 880 yards of 1:51.6 by Otto Peltzer, of Germany, in 1926.

A fortnight after the 1889 AAA 10, Kibblewhite gave a demonstration of his adaptability at Kennington Oval by taking on the finest half-miler in the country, William Pollock-Hill, of Oxford University (whom he had previously raced against at the 1888 AAA Championships mile), in a handicap event at the latter’s favoured distance and finishing 3rd. Only the month before Pollock-Hill had run the fastest ever 1000 yards by a Briton, 2:15 4/5, at Oxford. Later that afternoon of the Kennington Oval half-mile Kibblewhite won the three miles handicap by 50 yards in 15:06 1/5, having given 255 yards’ start to the 3rd-placed finisher.

When Thomas and Kibblewhite renewed rivalry at the AAA Championships four miles at Stamford Bridge on 29 June Thomas won again, and much more easily, as Kibblewhite dropped out, but already that afternoon he had obtained his first AAA title in dominating fashion, leading all the way in the mile and winning by 30 yards. He would successfully defend that title in 1890 and 1891, with a fastest time of 4:23 1/5, and thus became the first man to achieve such a triple at the AAA meeting that had even evaded the great Walter George.

An ever more favourable comparison with his distinguished Wiltshire mentor could be made after Kibblewhite’s three-mile win in his own club’s promotion at Stamford Bridge on 31 August in a time of 14:29 3/5 which took almost 10 seconds off George’s “World record” (no such official appellation existed then), again from 1884. The successive mile times were almost exactly 4:40, 5:00 and 4:50, and Kibblewhite did not actually win the race as it was a handicap event and he finished 20 yards adrift of an opportunist visitor named P. Crowther, from Wakefield, in Yorkshire, who had started 160 yards ahead. There’s no reason to suppose that Crowther was a pre-destined pacemaker as he no doubt had headed southwards to the capital with his eye on the winner’s prize. If the Spartan officials had wanted to set something up for a record-breaking attempt by their star club-man, they could surely have found someone in their own ranks of runners to be conveniently reeled in over the last lap or so.

On 14 September, Kibblewhite raced at the Paddington Recreation Grounds, which covered 21 acres in North London and was described as the only such venue in the city “available for the athletics sports of the masses”. There he very nearly beat his own record, and it must have been an astonishingly exciting race to watch because he crossed the line in 14:30 2/5, having made up 598 yards of the 600-yard start he had given to one H. Gale, of Finchley Harriers, who must have felt a storm approaching at his back as the Spartan Harrier bore down on him in the final straight. A week later, back at Kennington Oval, Kibblewhite knocked out another fast time, 14:36 4/5, and dead-heated with a club-mate named J. Swait, who had been given 100 yards’ start. It may well have been a deliberate gesture to share 1st place, but they tossed a coin to decide who would take the prize, and Kibblewhite made the correct call. Whether the 3rd-finisher could be described as being headed home or tailed off, he was another Spartan member, Charles Pearce, who also had a 100-yard handicap advantage at the start but would soon improve so much that he was pulled back to the “scratch” mark in further races and would win the AAA four miles in 1892.

Such was Kibblewhite’s public appeal by now that he even attracted the attention of a nationally known sporting “rhymester”, Albert Craig, who otherwise penned verse in praise of cricket or football. In a characteristic style, marked more by enthusiasm than erudition, he wrote about an impending race involving Kibblewhite and two of his most notable opponents, the aforementioned William Coad, of South London Harriers, and E. D. Rogers, of Southampton Harriers, the AAA four miles champion of 1886:

“Ten thousand spectators, all hearty and jovial

Are patiently waiting in painful suspense.

We’ve seen scores of similar scenes at the Oval

When the pitch of excitement has been most intense.

Some believe Kibblewhite’s King of the Road

And some go for Rogers, but I fancy Coad”.

Albert Craig’s poetic skills were somewhat erratic. In the next verse he rhymed “Coad” with “applaud”. Still, his readers didn’t seem to mind – Craig’s first job had been as a post-office clerk in Bradford, but he sold a thousand copies of his rhymes at his first attempt at a Yorkshire-v-Gloucestershire cricket match, earning as much as he would have done in two months of his usual employment, and so he promptly resigned and moved to London to set himself up as a full-time “rhymester”.

Cross-country running was a supreme test of strength and stamina for those runners of the late Victorian era. The National Championships had first been held in 1877 and the Southern in 1881. The 1890 Southern on 15 February took place over the customary 10-mile distance. The venue was Croydon Racecourse, in Surrey, and heavy rain fell throughout, ensuring that the going underfoot was even more clinging than usual. Kibblewhite took 1 hour 6 minutes 57 3/5 seconds to win the event and was followed home by Swait and a third Spartan Harrier, W. Bullen, for an easy team victory. Yet Spartan did not make the journey the next month to the National at Sutton Coldfield, in the Midlands, and the only two Southern clubs to do so were South London Harriers and Finchley Harriers.

Ironically, it would have been an easy excursion for Kibblewhite from his native village because Purton had its own railway station for 120 years from 1843 onwards. The individual champion for the second successive year was Edward Parry, of Salford Harriers, and after his first win he and Sid Thomas, 2nd in that race, had been brought together for a 10-mile track return match in Manchester and 10,000 spectators had paid £380 at the gate – worth 760 times that amount in 2017 income !

The remainder of the year was one prolonged triumph for Kibblewhite, and invariably in easy fashion. In April he won the AAA track 10 miles by almost 200 yards and would perhaps have had a harder day if Sid Thomas had been there, but the latter was away on an extended tour of the USA which even included racing indoors, though with no marked success. The AAA Championships on 12 July were at the Aston Lower Grounds, in Birmingham, and Kibblewhite not only retained his mile title but won the four miles by 50 yards in 20:16 2/5. Walter George had achieved the same double in 1880, 1882 and 1884.

Thomas and Kibblewhite met up again at the 1891 Southern Championships cross-country at Kensal Rise on 2 February, and Warren Roe related in his biography of Thomas that “training was stepped up at Ranelagh Harriers with the aim of improving the club’s performance … members were encouraged to compete in the LAC races at Stamford Bridge on Monday evenings in addition to two club runs from the ‘Green Man’ on Tuesdays and Thursdays”. The venue for those Southern Championships is now part of the urban sprawl of North-West London, but in the 1890s there was a dead-end road which led into the neighbouring woodlands to provide the competitors with a suitably rural cross-country route which covered almost 11 miles.

Ranelagh’s upgraded preparations did not work (a bit late in the day, perhaps ?) because Kibblewhite won that race again, with Thomas 3rd, and then added the National title the following month, with the defending champion, Edward Parry, 2nd. As this race was held at Arrowe Park, in Birkenhead, immediately across the River Mersey from Liverpool, the Spartan Harriers hierarchy must have changed their attitude towards supporting the event, though this view was not widely shared. Nine clubs took part, with Birchfield taking the team title from Finchley Harriers and Spartan, and the only other visitors from outside the North-West of England were the South London Harriers, who provided the 3rd finisher, Harry Heath. If anything, the team award was regarded more highly than individual honours, and it would seem that if clubs did not fancy their chances of a high placing they did not attend.

Arrowe Park remains a regularly-used cross-country venue at local and national level to this day, and another South London Harrier of a much later generation and rather greater fame, Gordon Pirie, would win the National there in 1954. I can personally vouch for the demands made upon runners by Arrowe Park’s lush turf or churned-up mud underfoot, having plodded round there often enough in Liverpool & District League races of the 1980s. Along one side of the park is the local hospital, and the smoke belching out from the incinerator chimney-stack hangs like an ominous pall over the labouring runners passing below. In 1985, when the women’s National was held there, and I was providing race commentary for the spectators, it was the infamous scene of anti-apartheid demonstrators invading the course to attack the British-naturalised South African, Zola Budd. Ill-informed, the intruders did not recognise Miss Budd and bundled into another runner instead … but that’s a story entirely incidental to the subject of this article, and must perhaps wait for a more suitable occasion to be related.

Kibblewhite’s next outing was at the South London Harriers’ track meeting at Kennington Oval on 11 April, where he won at five miles in an unexceptional 26:14 4/5, but the correspondent for “The Times” explained that the grass was “rather heavy”. Maybe the problem with the surface of the hallowed cricketing out-field took a while to be resolved because when Surrey opened their season against Leicestershire a month later the visiting captain, C.E. de Trafford, a son of the 2nd Baronet de Trafford, hit a vigorous 75 at a run a minute, but having scored only 17 “had an escape in the long field (Maurice Reed missed the catch)”. A week later, at Tufnell Park, in North London, Kibblewhite ran a respectable 14:51 2/5 for three miles, but that would remain his best for the year.

On 27 June, at Stamford Bridge, he completed an athletic hat-trick by winning his third successive AAA mile title, waiting till the last 20 yards to take the lead, and his best time of the season for that event came on 5 September at Trowbridge, in his native Wiltshire, when he ran 4:24 1/5. The only man of any nationality faster that year was the Irish-American, Tommy Conneff. with 4:21.3 a fortnight later in New York. Conneff would subsequently set two amateur “World records” and his 4:15 3/5 of 1895 would be unbeaten for 18 years. He was a regular visitor to England and had won the AAA mile in 1888, as previously mentioned.

Conneff apart, middle-distance and long-distance-running on the track was, to all intents and purposes, a British preserve. Of the 14 men who ran faster than 4:30 for the mile during 1891, eight were English, while F. Owen-Jones, of Queen’s Park Harriers, would certainly have had Welsh lineage and the ornately-named C.P. Robertson-Glasgow, of Oxford University (father of a future cricketer and cricket writer of renown, R.C. Robertson-Glasgow), was Scottish, as you might have guessed. Queen’s Park Harriers, founded in North London in 1887, for some years held their summer-time club races in local streets because they had no headquarters of their own. Robertson-Glasgow’s son, by the way, earned the nickname “Crusoe” because a perplexed batsman once dismissed by his bowling thought his name was “Robinson Crusoe” !

Conneff was in a class of his own among American milers, and the only other man of ability remotely akin to the leading Britons was a US-based Canadian, George Orton, whose long and varied career would culminate in winning one of the two steeplechase events at the 1900 Paris Olympics and taking 3rd place in the 400 metres hurdles. At three miles all of the 14 who ran 15:30 or faster in 1891 were English. There was no competition of any note at 1500 metres other than in France, where the fastest time was equivalent to a mile in about 4:40, and none at all at 5000 metres. Even the unofficial pre-IAAF “records” do not start until 1895 for the shorter distance and 1900 for the longer, when Charles Bennett, won the Olympic team race. Earlier in his competitive career Bennett had been a lesser opponent of Kibblewhite’s and must have shared common interests because he was a railway-engine driver by occupation, based at Bournemouth, in Dorset,

In 1892 the Spartan Harriers club was thrown into crisis when Kibblewhite left to join Essex Beagles (now Newham & Essex Beagles AC) in the company of other leading runners from his club (Swait, Bullen and a highly promising 19-year-old, George Martin, who would later be twice AAA steeplechase champion). Others from the Tower AC and Walthamstow Harriers made the same switch, including another of the leading distance-men of the day, Charles Willers, who within 18 months would become a World record-holder, no less ! Clubs tended to flourish briefly and then go defunct in that era, and Walthamstow Harriers seem to have suffered the same fate as Spartan. Oddly, though, in 1901 another club in the London area named Spartan Harries was formed, while the same year Priory Harriers was founded and became Walthamstow YMCA Harriers after World War I and is now amalgamated with Orion Harriers – see the informative Spartan and Orion websites for further details.

Essex Beagles had changed its name from Beaumont Harriers the previous year, and an excellent account of the proceedings written by Tony Benton is now to be found a century-and-a-quarter later on the club’s website. This refers to “the desired break from the Harrier tradition and the club’s entry into senior athletics in general”, and elsewhere it states that Kibblewhite won £1200 in prizes during his competitive career, equivalent to more than 900 times that amount in 2017 wealth terms (!), adding – maybe with justification – that “he probably also pocketed a tidy sum in appearance money”. One can’t help feeling that some sort of recruitment drive had gone on to lure away Kibblewhite and Willers from their well-established previous clubs, and the unfortunate repercussions were that within a few years the deprived Spartan Harriers would cease to exist.

Whatever “desired break” envisaged by Essex Beagles, they had precipitated a sad break with history because the Spartan club had been one of the very first to have been founded in England (and therefore the World) and had been active since at least 1874. It had taken part in the inaugural National Cross-Country Championships of 1877 and won the team title the next year. Furthermore, one of their members, C.F. Turner, who was himself a capable distance-runner, was a delegate at the meeting in Oxford in April 1880 at which the AAA was formed and which then held its first Championships three months later. At the 1881 Championships a Spartan Harrier named W. Lock failed by less than a stride to win the 880 yards, while another club member, T. Shore, who carried out the delicate and demanding duties of setting the handicaps for runners, served as a vice-president of the AAA in the 1880s.

Handicapping was at the heart of the structure of athletics meetings, as Montague Shearman explained in his 1887 history: “One of the officials upon whom in a great measure success depends, although he is often not present at the meeting itself, is the handicapper. At most gatherings nowadays, there are more handicaps than level races; often indeed, especially in London, there are no level races at all … as meetings of this description take place by scores in every part of the country, it is obvious that none but trained handicappers, who regularly study the art, can be trusted to bring the men together”. Handicappers were paid for their work, and Shearman noted that “at least a score of men in one or another part of the kingdom are making a comfortable addition to their income by the exercise of their talents in this direction”.

Club membership, incidentally, could be a free-and-easy affair then because Sid Thomas, for example, represented not only Ranelagh during 1892 but also London AC and a Kildare AC (presumably London-based, not in Ireland) at various times, starting his track season by winning the AAA 10 miles at Stamford Bridge on 26 March by 300 yards. It was not until 1897 that the AAA introduced a “first claim” rule to try to prevent athletes changing clubs or being “poached” without some sort of probation being served.

Both the Southern and the National cross-country events of 1892 were held at the Domesday Book village of Ockham, in Surrey – “level” races, even if the courses weren’t ! – and the Essex Beagles reinforcements returned the investment made in them. Though beaten into 2nd place by Finchley Harriers at the Southern, the Beagles then tied with Birchfield at the National, as the two clubs between them provided 12 of the first 22 finishers, with the ex-Spartan Harrier, Swait, vitally coming in 22nd to ensure that team honours were shared. Both races were won by the South London Harrier, Harry Heath, who had placed 3rd to Kibblewhite in the previous year’s National. Charles Willers helped the Beagles to their team successes, placing 6th in the National, but Kibblewhite was absent for good reason because he had yet to make the transfer.

Neither was he among the 19 starters for the AAA 10, and when he lost by three yards to Harry Heath in an intensely exciting three miles at Kennington Oval on 9 April. Kibblewhite’s affiliation was listed in the results as merely “Swindon”. Then at the Essex Beagles meeting at Stamford Bridge on 7 May he met Heath again in a specially-arranged two-mile match in which the pair were billed as the “One mile champion” and the “Cross-country champion”. Kibblewhite suffered a further reverse, and maybe a humiliating one. He had led most of the way, but Heath passed him on the last lap and Kibblewhite stopped 30 yards from the finish. It was not the most auspicious of circumstances in which to introduce himself to his new club, but the deal was clearly struck there because in his next race on 4 June his affiliation was listed as “Essex Beagles”.

Did Kibblewhire but know it, the balance of distance-running power in England was changing. The same afternoon as he was racing at the Oval, there was another enthusiastic crowd a few miles away across London, at Stamford Bridge, despite the alternative attraction of the Oxford-v-Cambridge Boat Race on the River Thames that day. They were rewarded by seeing Sid Thomas set a 15 miles record of 1:22:15 3/5 (plus other records for 12, 13 and 14 miles on the way) in an event specially organised for him by his own club, Ranelagh. More than two decades later, when the IAAF was to first meet in 1914 to establish an inaugural list of official World records, they accepted the next improvement on Thomas’s time – 1:20:04 3/5 in 1902 by Fred Appleby, again at Stamford Bridge – and the event would continue to be recognised until 1979. The last holder was the outstanding marathon man, Bill Rodgers, with 1:11:43.1, which would have brought him home the best part of nine laps ahead of Thomas !

It would have done nothing for Kibblewhitee’s disturbed peace of mind after his two-mile defeat by Harry Heath to have later learned that the five miles record, previously held by Walter George, had been broken in Dublin that same day by William (“Sonny”) Morton, of Salford Harriers, who was the previous year’s AAA four miles and 10 miles champion. Morton had also that season beaten the visiting US champion, Tommy Conneff, in a five-mile match race at Belle Vue, Manchester, which attracted 10,000 spectators and made £250 profit for the Salford club. The average weekly wage for a working man then was less than £1.

Improved form brought Kibblewhite a notable four-mile success at the Ranelagh Harriers sports at Stamford Bridge on 4 June, winning in 20:17 1/10 ahead of Charles Willers, Fred Bacon (a future mile record-holder) and Sid Thomas. Every Saturday throughout the summer and into the autumn there would be an athletics meeting at the famous stadium, each sponsored by a club or association, and it would be at one of these in September that Kibblewhite and Edgar Bredin would meet in the second of their memorable clashes at 1000 yards. At the AAA Championships on 2 July (again at Stamford Bridge), Kibblewhite won the four miles in 19:50 3/5 which was within 11 seconds of Walter George’s record, but the race was marred by the crowd surging on to the track and so enabling only one other runner to finish..

Essex Beagles won the team titles at both the Southern and National cross-country events in 1893, at Ockham and at Redditch, in Worcestershire, respectively. Harry Heath was also a double winner, and Kibblewhite 3rd on each occasion. This, though, was to be his last year of competition, and maybe he already knew it. The Beagles would continue to be a major force in cross-country for the next eight years, always in the top five National team placings and winning in 1901, with George Martin their most durable scorer throughout. As a side-issue it’s worth noting that such are the vagaries of club resources that it would be almost another 50 years before the Beagles even placed in the top 10 teams at the National (with future marathon record-breaker Jim Peters their leading finisher) and more than a century before they came near to matching their sequence of 1892-1902, with top seven finishes every year from 2003 to 2013 and the individual winner in the last two years, Keith Gerrard.

Sid Thomas won the third of his four AAA 10 miles titles in March of 1893, and on 7 May he and Charles Willers met in a four-mile challenge race arranged by Essex Beagles as part of their “Athletic Carnival” at Stamford Bridge. Warren Roe says in his biography of Thomas that “for some time the talk had been that Sid was spoiling for a match with Charles Willers” – in other words, Kibblewhite didn’t enter into the equation.

Maybe Kibblewhite realised that he was not in the form that warranted such a contest. Maybe he rankled at not being asked. We don’t know. Thomas even gave Willers 60 yards’ start but caught him at 2¼ miles and won by half that margin, which suggests he may have been content just to keep his opponent at bay. Yet Thomas still broke Walter George’s seven-year-old record by three-fifths of a second, in 19:39 1/5. The following Saturday, back once more at Stamford Bridge, Thomas took away another of Walter George’s records with 6:53 2/5 for 1½ miles and later in the afternoon beat Harry Heath at three miles to give the large crowd full value for their entrance money.

On successive Saturdays, 3 and 10 June, Thomas and Willers met again and records continued to tumble. Firstly, in an inter-club three miles involving Blackheath Harriers, Essex Beagles, Highgate Harriers, Ranelagh Harriers and Walthamstow Harriers, at Stamford Bridge, Thomas led Willers all the way and won by five yards as both broke Kibblewhite’s record. Thomas’s time of 14:24.0 would last 10 years until the legendary Alfred Shrubb came on the scene. The week later, at the Paddington Recreation Grounds, where the London & North Western Railway were holding their annual sports, Willers took his turn, setting a four-mile record of 19:33 4/5, with Charles Pearce 2nd and Thomas 3rd. Then the same three met in the AAA Championships four miles at Northampton on 1 July, with Thomas the winner in outside 20 minutes, which may have been viewed by some of the spectators as rather an anti-climax.

Kibblewhite had been overtaken. He had seen record after record broken by others. His own three-mile time had been beaten by not one man but two. Even the milers were improving as Tommy Conneff set a new amateur best of 4:17 3/5 in the USA. Kibblewhite didn’t race again – either discouraged or content to let others take over. As it happens, we had also seen the best of both Sid Thomas and Charles Willers. Thomas ran a few more races, including winning another AAA 10 miles title, but was one of those caught up in the round of disqualifications for life by the AAA in 1896 and then had a desultory career as a professional, achieving nothing of note. Willers seems to have shot his bolt, thereafter achieving only a very distant 3rd place in the 1895 AAA 10 miles.

The subsequent lives of Sid Thomas and James Kibblewhite contrasted starkly. By the London Olympic year of 1908 Thomas was in desperate straits, but Kibblewhite was happily back at his railway employment. A benefit meeting had been organised for Thomas in March of that year at Stamford Bridge, attended by 5000 people, but within a few months he was arrested by the police for begging and spent the rest of his life in poverty, dying in 1942. Kibblewhite made a cheerfully brief return to the track in the August of 1908, competing in the heats of the veterans’ 80 yards at the London Railway Amateur Association sports alongside one of his former rivals, Charles Pearce. Kibblewhite died in Swindon a year before Sid Thomas, on 6 November 1941 at the age of 75, and clearly had spent the rest of his life in his native village as he married and all of his children were born there.

The news of Sid Thomas’s death in obscurity had only filtered through to the athletics community after some months, and he was paid a fulsome tribute in memoriam by the most respected of athletics writers of that era, Joe Binks, who had been the correspondent for the “News of the World” Sunday newspaper since 1902 and would continue in that role until his retirement at the age of 82 in 1956. Binks had himself been AAA mile champion in 1902 in a British amateur record time of 4:16.8, and so had competed regularly against both Thomas and Kibblewhite. Binks described Thomas as “the most graceful distance-runner of all time” and remembered fondly the races between Thomas and Jimmy Kibblewhite.

Athletics historians are very well served for sources of information about athletes in the late 19th Century because, apart from the work of Peter Lovesey, the acknowledged foremost expert on that era, there have been biographies published in recent years of almost every middle-distance and long-distance runner of renown from the 1860s to the eve of World War I. Among this elite are Jack White Teddy Mills, Deerfoot, Walter George, William Snook, Sydney Thomas and Alfred Shrubb, with the principal authors being Warren Roe and Rob Hadgraft. Maybe Kibblewhite now merits such attention

My thanks to Peter Lovesey, Tony Benton and Chris Holloway for valuable information..

Leave a Comment