Snell v Tulloh v Thomas

Mile, Wanganui, New Zealand

January 27, 1962

Great Races # 19

Early in 1962 a small coastal town in New Zealand hit the headlines across the world. Wanganui was the site of an unexpected Mile world record by Peter Snell, the current 800 Olympic champion. He had never run under 4:00. So although his well-publicized attempt at the first sub-four Mile in New Zealand looked feasible, anything close to Herb Elliott’s 3:54.5 WR was not expected.

|

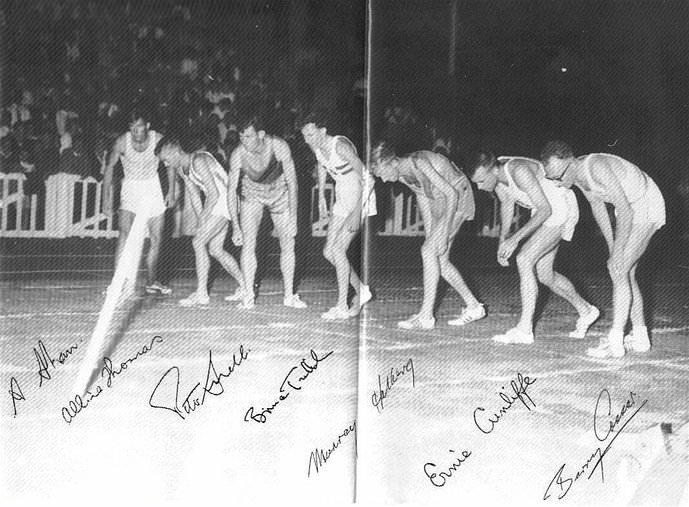

| From Left: Alex Shaw, Albie Thomas, Peter Snell, Bruce Tulloh, Murray Halberg, Ernie Cunliffe, Barry Cossar. |

But the odds seemed stacked against even a four-minute Mile. Torrential rain was forecast for the area, which was crucial since the race was to be held on a grass track in Wanganui’s Cook’s Gardens. And then the track itself, although in good condition, was only 385 yards (352m) long. To make matters worse, a running friend of Snell’s had drowned that morning, and although this tragedy was kept from Snell, it did affect significantly the performance of Murray Halberg, one of the assigned pacemakers.

Snell, fresh from a 1:47.1 PB over 880 and an “easy” 4:01.2 Mile, attracted a capacity 16,000 crowd to the natural amphitheatre in Cook’s Gardens—over half the population of Wanganui. The huge black storm-cloud overhead fortunately didn’t release more than a few drops, but, as Halberg later wrote, “Somehow it managed to electrify or intensify the atmosphere, making the dark night even darker and the track lights even brighter.” Halberg, A Clean Pair of Heels, p. 134)

Aside from Snell himself, six other runners were entered for the feature Mile race. There were two sub-4 milers: Albie Thomas of Australia and Murray Halberg. Thomas, who had paced compatriot Herb Elliott to 1,500 and Mile WRs in 1958, was concentrating on the Mile at this time, despite having broken the WRs for Two Miles and Three Miles. As an Australian, it was unlikely that he would help Snell. Halberg, on the other hand, had agreed to keep the pace going on the third lap. As the New Zealand record-holder at 3:57.5, which was four seconds faster than Snell’s best, he had the ability to outlast his fellow Kiwi on the last lap.

|

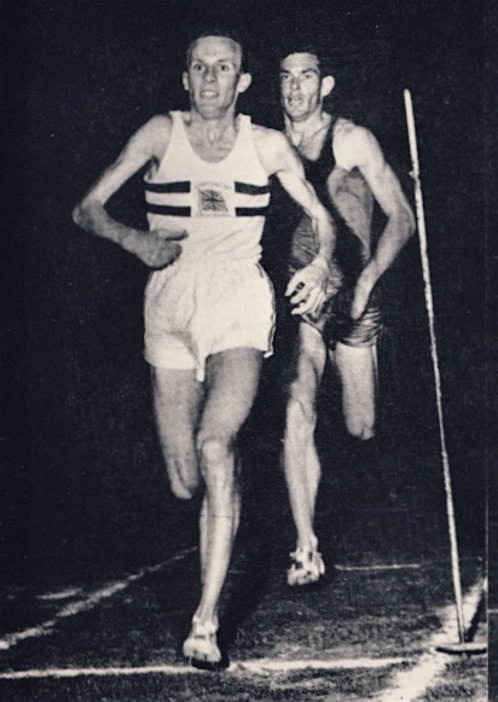

| Barry Cossar starts to open a gap on Halberg. Snell is about to move into second. Tulloh is fourth. |

Then there was barefoot-runner Bruce Tulloh, a British Three-Mile specialist. Tulloh had told the press, “I’ll give Snell a go, even if I don’t finish properly.” (Norman Harris, Lap of Honour, p.137) He had run close to 4:00 before and was in good form, as his recent 8:33.9 Two Miles had shown. In this race he had fought with WR-holder Halberg for the whole last lap, losing by only 0.1 of a second. American half-miler Ernie Cunliffe, who had been an Olympic 800 semi-finalist in Rome and who had ranked fifth and sixth in the world in 1960 and 1961, was another entrant. On tour in New Zealand, Cunliffe had already shown form in pushing Snell to a fast 1:48.2 on a crumbling track. His form over four laps was unknown. And rounding out the seven-man field were two local runners: Barry Cossar and Alex Shaw.

The plan for a four-minute mile was simple. Barry Cossar was to take at least the first lap. If he was unable to maintain the pace to 880, Ernie Cunliffe said he was willing to help. On the third crucial lap, Halberg would ensure that the bell was reached in 3:00. Then it was up to Snell. But this pacemaking plan was not achieved, and when the bell rang, Snell was in for a big surprise.

Snell prepared carefully. In the morning, he did a 30-min morning jog. Later, he took afternoon tea with family and friends before resting in his hotel room. He arrived at Cook’s Gardens at 6:00 pm, more than three hours before his race. He was not in a great frame of mind as his coach, Arthur Lydiard, had told the press that he would run as fast as 3:55. This unwelcome added extra pressure.

|

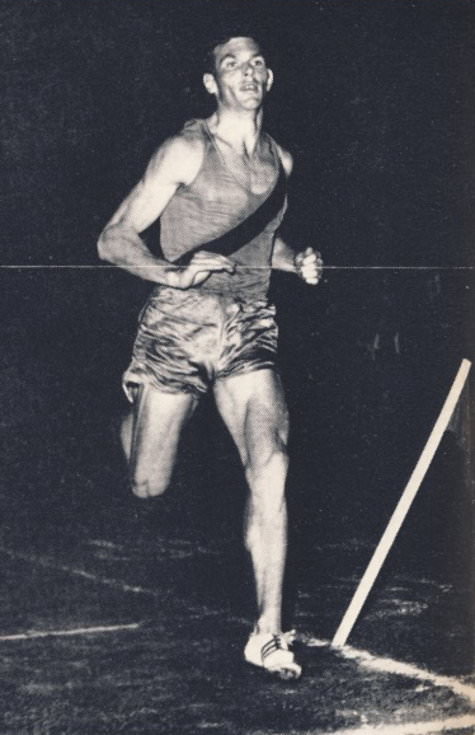

| Tulloh takes the lead at the bell. |

While waiting for his race, Snell noted that the track was “not particularly beautiful” but “as a running surface in the conditions that prevailed, it was excellent.” (Snell, NoBugles, No Drums, p. 91) During the earlier events, the inside lane was left untouched for the big race. As the time for the race approached, it was clear that the meet was well behind schedule, so some events were held up for the Mile to go ahead at 9:30 pm as planned. Under the lights, the seven competitors lined up. There was not a breath of wind.

On the 385-yard track, the race started on the back straight and took 4 1/2 laps for a mile. As Barry Cossar surged to the front, Snell started off easily in last place: “I didn’t leap away with my usual keenness…taking the view that there plenty of others in the race to help me.” (Snell, p. 92)

Cossar did a fine job, taking the field through 440 in close to 60 seconds. Snell, running second was just over 60.0 (Tulloh later said 60.2, while other reports gave 60.7). Cossar continued to lead to the half way point, maintaining the required speed (1:59). Snell in third at 880, noticed that Halberg in front of him was not staying with Cossar. He had to act: “Impatience got the best of me then. I moved into the lead myself, determined that I would make the 3/4 mark in 3:00…. I concentrated purely on the time and on keeping my running as relaxed as possible.” (Snell, p. 92)

The crowd, sensing that the four-minute mile was on, went wild as Snell took over. Halberg also passed Cossar, but he was unable to help his fellow countryman. Instead it was the barefoot Tulloh who was tracking Snell. It was a contrast of running styles: Snell, the burly 800-runner (80kg/176lbs)with muscular legs and a powerful stride; the emaciated Tulloh (54kg/119 lbs) who literally scampered over the ground with his thin arms barely moving. The time at the bell (2:58) was perfect for Snell. Everything had worked out perfectly, although not quite as planned.

Then came the big surprise: Tulloh whipped by into the lead. Snell recalled that this was just the stimulus he needed. He waited until the back straight to make his effort: “I abandoned the studied relaxation of my running and let go with my finishing drive…. I found myself running in complete freedom from restraint. I was holding nothing back and I don’t think I’ve ever felt such a glorious feeling of strength and speed without strain….” (Snell, p. 93)

Snell remembers that he heard crowd for first time on entering final straight: “Still there was no conscious effort and I flew through the tape in full free flight.” (Snell, p. 92) Because of a misprint in the program listing Elliott’s WR as 3:54.4 instead of 3:54.5, it was first believed that Snell had only equaled the WR. But this was soon corrected—to another roar from the crowd.

|

| Snell hits the tape at 3:54.4. |

Years later, Snell admitted to Jim Denison that his WR time had “shocked” him. Surprisingly, he went on to say that he was not altogether pleased with his effort: “It was unfortunate that I wasn’t more conscious of working hard and pushing the pace in that race because I think I could have run even faster. I had way too much energy left at the finish.” (Denison, Bannisterand Beyond, p. 71)

Behind Snell, the amazing Tulloh managed to finish under 4:00 with 3:59.3. Halberg, who finished fourth in 4:06.6, remembers Tulloh’s reaction: “In the middle of it all, the near-demented Bruce Tulloh danced up and down the field. ‘I must have broken four minutes. I must have. I wasn’t that far behind Snell,’ he kept saying.” (Halberg, p.135) Behind Tulloh, but ahead of Halberg, Albie Thomas put in a good time of 4:03.5 for third place.

But this was Snell’s night. Although his pacing plans had gone somewhat awry, he had taken charge of the race with great authority. In the cool and still New Zealand dusk, under the floodlights and in front of an ecstatic crowd, he had run a Mile faster than anyone else. He had surprised everyone except his coach and had put Wanganui on the map. It was the last Mile WR run on a grass track. (After the race, the 385-yard track was re-measured to ensure that Snell’s WR was valid.)

So his coach Arthur Lydiard had been correct in his 3:55 forecast. He no doubt saw that the combination of Snell’s 800 speed with his long-distance training (See Snell Profile) would translate into a fast Mile time. And Snell himself was well aware of his Mile potential, having told Neil Allen six months earlier, “I really would like to have a serious crack at the Mile. I believe I am far from my potential over four laps.” (Times, January 29, 1962) Herb Elliott was not surprised that Snell had taken his away his WR: “His past performances suggested that he had it in him. I’d have been surprised if it had been anybody else.” (Times, January 29, 1962)

Postscript

|

| 31 years later, the seven runners from the original race line up for a re-enactment. |

In 1992, there was an attempt to arrange a 30-year reunion with all seven runners from this race. This reunion took place a year late on January 27, 1993, because of funding issues that had delayed the redevelopment of Cook’s Gardens. Snell and Cunliffe came from the USA, Tulloh from England and Thomas from Australia to join the three New Zealand runners, Halberg, Shaw and Cossar.

Peter Snell told the 2,500 crowd how the 1962 race had changed his life: “I had done well at 800, but the world Mile record propelled me into the limelight worldwide.”

The seven competitors lined up for the photographers in exactly the same starting positions and poses. Then they re-enacted the last 660 yards of the 1962 race to the accompaniment of the original radio commentary of the whole race. As Ernie Cunliffe has described it, “we paced ourselves to be sure to hit the finish line in the proper order and at the correct finish time.” Thus the seven runners took around the full four minutes of the original race to run 660 yards. And of course Snell won again!

A cruel quirk of fate tainted both the original race and the reunion. On the day of the 1962 race Peter Snell lost his good friend Peter Hitchen in a drowning accident; thirty years later, on the night before the reunion, Peter Snell’s mother passed away.

Leave a Comment