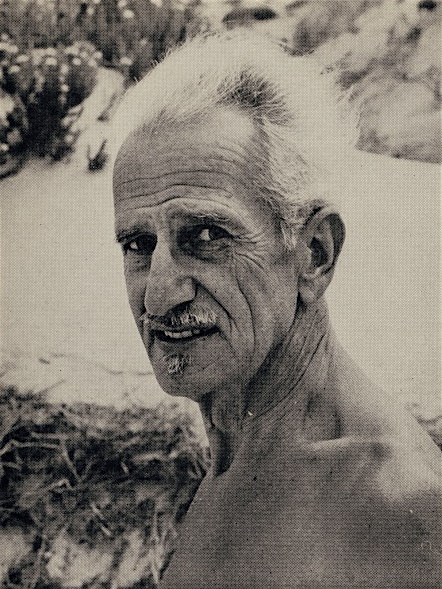

PERCY CERUTTY

1895-1975

|

To call Percy Cerutty passionate would be an understatement. To call Percy Cerutty eccentric would also be an understatement. To call Percy Cerutty a deep thinker would be accurate. To call Percy Cerutty an inspirational coach would be accurate too, although he was too extreme for many athletes. Cerutty’s eccentricities, which were fuelled by his unbounded enthusiasm, often got him into trouble. His run-ins with authorities led to his being passed over for a coaching job at Melbourne University that opened up just before the 1956 Olympics. Cerutty was already the most successful coach in the Melbourne area when Franz Stampfl was brought in from England. “I was the local boy,” he wrote later. It was understandable that Cerutty was sorely miffed, but he would never have settled into the discipline of a university position. Indeed, he claimed that he would have refused the job: “Nothing could have appealed to me less that having to organize classes and lectures.” (Cerutty, Sport Is My Life, 53)

Cerutty had enough pride to refuse to accept Stampfl as “my official coach or as one superior in knowledge.” (Cerutty, SIML, p.57) He was in trouble with the Victoria AAA for charging a fee for his services, even being ordered off the track in one instance. But his star was rising with Albie Thomas, Dave Power and, for short time, Ron Clarke. Then Herb Elliott joined the Cerutty camp. Soon the press built up a huge rivalry between Cerutty’s top runner Elliott and Stampfl’s top runner Merv Lincoln. There were many close races between the two milers, but as Cerutty proudly wrote of Lincoln, “Never did he once beat my Herb Elliott.” (Cerutty, SIML, 58)

|

Cerutty confirmed his rivalry with Stampfl, paying him the following back-handed compliment: “It is doubtful if Australia would have reached the world-renown and eminence it did in middle-distance running had not Franz Stampfl come to this country. I admit it, his coming here acted as a challenge to me and aroused me from a certain athletic lethargy that seemed to have fallen upon me with the decline of Landy, Perry, Hall and my original group.” (Cerutty, SIML, p.60)

Self-Development

His ground-breaking coaching principles had grown out of a severe personal crisis and breakdown at the age of 43, when he was told by a doctor that he would never work again and had only two years to live. Shocked by this death sentence, he set about educating himself. First he read books on medicine, physiology and nutrition. These studies led to him becoming a vegetarian who rarely cooked his vegetables. Next he studied mysticism and psychology, Krishnamurti being his main influence. Of course physical fitness came into the picture too. Cerutty was greatly influenced by Physical Strength and How I Acquired It by George Hackenschmidt, a famous wrestler and an early practitioner of weight training. He also discovered the writing of English distance-runner Arthur Newton. His led to him taking up running himself. At first he could only run very slowly, doing little more than a shuffle.

In less than a year, Cerutty was strong enough to join a walking club. A year later he completed a 113K walk. Weight training was making him stronger as well. The next step was entering races. All this time he was researching; he was fascinated by movement, especially the movement of animals. With all the knowledge he had absorbed, he started writing. Then he found his first athletes to coach: 18-year-old John Pottage and then Gordon Stanley. Cerutty at this point was inspired by the success of Swedes Hägg and Andersson (See Profiles), especially since their training in natural environments tallied with his own beliefs. By 1944, when he was 49 years old, Cerutty’s own mile time dropped to 5:10. The next year he did a 500-mile hike, covering the last 100 in 23.75 hours. And then in December, just before his 51st birthday, he ran his first marathon in 3:02.

|

|

Cerutty leads his athletes up a Portsea sand dune. |

Becoming a Coach

As he became more involved with his coaching of Pottage and Stanley, Cerutty realised that he had skills in that area. So in 1946 he bought a 3/4-acre property in Portsea and started constructing a training camp. Later that year he ran the 80 miles from his Portsea property to Melbourne as a publicity stunt for his new venture. He also developed the concept of a “stotan” (a mixture of stoic and Spartan) to describe the kind of person he wanted to develop. He was now ready to take in new athletes.

The first notable arrival was Les Perry. Cerutty had seen him collapse in the last lap of a Three Miles and was impressed by his courage. It took Perry a year to recover from this collapse. Then he saw an ad Cerutty had placed in a Melbourne paper for those interested in distance running. So he went down to Portsea. Soon he was national three-mile champion.

Next came Don MacMillan—introduced to Cerutty by Perry. MacMillan quickly became the national mile champion and was second in the 1950 Centennial Games Mile in New Zealand behind Bannister. Cerutty clearly had the ability to coach: in a very short time Cerutty had taken both Perry and MacMillan to a new level of performance.

Profesional Coach

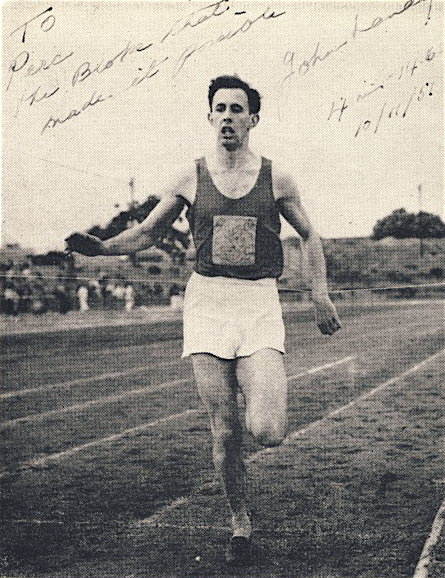

|

| John Landy's dedicationto Cerutty:"To Perce, the bloke that made it possible." |

At 56, Cerutty ended his competitive career and focused on coaching. He soon had a large group of runners who followed his often original training methods: sand-hill running, bark-mulch-trail running, weight lifting. He would charge a fee for coaching sessions, although top-class runners were not charged. A new prospect, John Landy, was talked into training with him. He was a 4:43 miler at this point; after four months of coaching by Cerutty, he ran 4:17. But the mild-mannered Landy was always uncomfortable with Cerutty’s abrasive enthusiasm. Landy later broke with Cerutty and trained alone with his own system that he had developed after discussions with Emil Zatopek and other European runners.

Cerutty had four athletes in the 1952 Olympics: MacMillan, Landy, Perry and marathoner Prentice. This was quite an achievement for the self-educated and relatively inexperienced coach. Cerutty himself made quite an impact in Helsinki with his flamboyant showmanship. On being introduced to Bannister, he said: “So you’re Bannister. We’ve come to do you.” (Sims, Why Die?, p.118) But his athletes did not fare well; only Perry, who was sixth in the 5000 in a PB, ran up to expectations. Landy ran poorly, failing to get through his heat, and Macmillan was ninth in the 1,500 final.

After breaking with both Perry and Landy, Cerutty’s coaching hit a low patch for a few years. He did coach Dave Stephens for a short time, but Stephens was too much of a free spirit to stay with him for long. Cerutty did have one success in the Melbourne Olympics: Albie Thomas. He had only worked with Thomas for a short time before the Games but was able to help the young runner to make the team when he didn’t expect to. Then Thomas surprised everyone to finish a wonderful 5th in the 5,000 final. Cerutty was everywhere during the Games, talking to as many people as possible and hatching big plans for the 1958 Empire Games and the 1960 Olympics. Indeed, he was about to enter the most successful period of his coaching career.

|

| Herb Elliott follows his coach. |

Herb Elliott had been in the stands for the Melbourne Games and was especially impressed by Kuts’s 10.000 victory. He was just 18 when Percy began coaching him. He came as a 4:20 miler; within a few months he was down to 4:06, a world junior record. Soon after he ran another 4:06 and then dropped to 4:04.4. At the end of the 1956-7 season he ran 880 in 1:49.3, which was just 1.8 seconds outside the WR. Following a winter break away from Cerutty, Elliott returned to Portsea and soon ran a 3:59 mile. Then early in 1958 Elliott beat the top Australian miler Merv Lincoln, both runners dipping under 4. Clearly Cerutty had a world-beater in his stable.

His Greatest Successes

The 1958 European season saw Cerutty’s athletes running superbly, claiming two doubles at the Empire Games. Elliott won the 880 and Mile, while Dave Power, who had been training under Cerutty since 1956, won the Six Miles and the Marathon. Immediately after the Games, Elliott’s stunned the world with a 3:54.5 WR in Dublin. Cerutty’s reputation in Europe skyrocketed. He was offered a five-year coaching contract in Sweden. Nevertheless, he returned home as he wanted to keep building up his Portsea camp. And runners did flock there.

Cerutty now focused on getting Elliott ready for the Rome Olympics. After a quiet year in 1959, Elliott ran a couple of sub-4s in February of 1960. Later in June he sharpened his competitive edge in the USA. Cerutty had him in perfect condition for the August Olympics. He talked to Elliott a lot before the race and told him that the WR was there for the taking and that he should use his instincts to decide on a strategy. Percy planned to wave a yellow T-shirt if Herb was on WR pace on the last lap. Elliott surged into the lead with 500 to go (See Great Races #13). At this stage Cerutty vaulted a wire fence and crossed a moat to get beside the track to wave to Elliott. Waving his T-shirt, Cerutty was dragged off the track and never saw Elliott breast the tape in WR time. Nevertheless, he still somehow managed to stroll back on to the track again to congratulate his athlete.

“When I learned that a new world mark…had been set,” Elliott wrote later, “I remembered with gratitude Percy. Percy’s encouragement, his outrageous pranks and even his diverting clashes with officials and gatekeepers made him worth his weight in gold. (Elliott, The Golden Mile, pp.106-7)

|

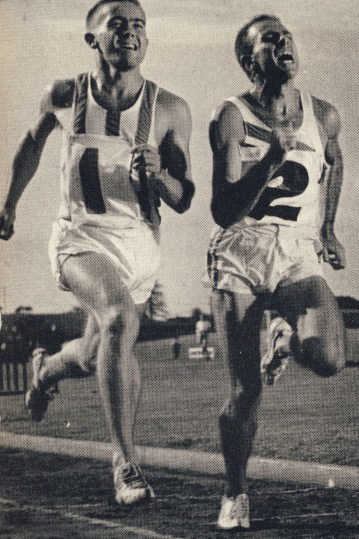

| Two world-class runners who were coached by Cerutty:Albie Thomas (1) and Dave Power. |

Cerutty had another big success in Rome. His other athlete, Dave Power, won a fine bronze in 10,000, The 1960 Olympics was Cerutty’s peak as a coach. He even tried to get credit for Halberg’s 5,000 win, but Halberg was quick to set the record straight and pay tribute to his coach, Arthur Lydiard.

There were no more world-class Cerutty runners after Elliot. Percy still worked hard at the camp, but the best Aussie runners did not train there. Now 65, he spent a lot of time writing. Ron Clarke was breaking many world records in the 1960s, but he did not respond to any of Cerutty’s overtures. Gradually Percy moved more to writing, although he still courted publicity at every opportunity. In the 1960s he published five books: Athletics: How to Become a Champion (1960) Middle-Distance Running (1964), Sport Is My Life (1966), Be Fit or Be Damned (1967), Success in Sport and Life (1967). The first three were specific to competitive running; the last two were aimed at a general readership.

Conclusion

Graem Sims’ fine book Why Die? summarizes Cerutty‘s impressive coaching legacy: “Though sports science would eventually embrace resistance training, especially hill work and soft-sand running, formalize his annual cycle of conditioning and call it periodisation, uniformly take up weight training as an athletic foundation stone, and incorporate visualization as a means of focus, Percy’s overall philosophy would remain outside the square.” (Sims, WD, 279) Of course Cerutty’s intellectualised philosophy of life is rather over the top for most young athletes—even Elliott’s religious beliefs remained intact despite “Percy’s teachings” (Elliott, GM, p.174). But from my personal experience as a runner in the late 50s and 60s, he opened up new vistas for runners; he inspired them to run barefoot, to seek out sand dunes and to renew contact with nature. And no one at that time pushed weight training as much as he did. Thus Cerutty definitely changed the approach to running all across the world. Above all, he offered runners an escape from the grind of track training.

18 Comments