Maurice Herriott Profile

b. 1939

|

While many of his international rivals were being financially supported by their countries, 1964 Olympic Steeplechase silver-medalist Maurice Herriott had to work a 45-hour week on a factory production line. Nevertheless, he managed to train three times a day and perform at international level for eleven years from 1958 to 1968. During these years Herriott was British Steeplechase champion eight times, won silver medals in two major games, lowered the UK Steeplechase record six times from 8:41.2 to 8:32.4, and won countless international races for his country.

School Days

At an early age, Maurice Herriott learned about hard physical work. As a schoolboy in Birmingham, he had a job delivering heavy loads of groceries on a bicycle. His early sport activity was football, playing “in the middle” for Birmingham Boys. His running ability suddenly became apparent when he was 13. He surprised everyone by winning his school’s trial for the Birmingham cross-country championships. And he surprised them all again when he finished second in the big race.

This race was a defining moment in Herriott’s life, for watching this race was Tom Heeley, a former Marathon runner and a coach at the local Sparkhill Harriers club. As Herriott recalls 60 years later, “Tom was the first person to come up to me after the race. He asked me if I’d like to join Sparkhill Harriers. I joined Sparkhill, and I’m honoured to say I’m a life member.” From this moment running became his sport, and Tom Heeley became his coach.

Fortunately, Heeley did not push the 13-year-old: “Tom said, ‘Just enjoy it.' They didn’t even push me to run in races.” Still, Herriott gradually became involved in cross-country races organized by the competitive Birmingham and District League, which was dominated by the Coventry Godiva club.

Full-Time Job

A big change in his life came at age 15: “I left school on a Friday and started work on the Saturday at BSA Motorcycles.” The tough assembly-line job kept him on his feet all day. Meanwhile he kept up his running for Sparkhill Harriers. Then a bizarre incident on the streets of Birmingham turned his interest towards the Steeplechase. On his way home from a cinema with friends, he tried to hurdle a newspaper notice board and ended up in hospital with a broken collar bone. Smarting from this humiliating accident, he asked his coach if he could learn to hurdle: “Tom said, ‘Why don’t you have a go at steeplechasing?’ I actually trained with Tom for a whole year just learning how to hurdle. I didn’t race for a year, just learned how to hurdle. Tom taught me hurdling from nothing; I literally started by stepping over, working up [the height] from one foot to two to three.” From these humble beginnings, he was on his way to becoming one of the finest Steeplechase hurdlers, whose technique was admired by one of the greatest, Kip Keino.

First Steeplechases

In 1957 Herriott ran his first Steeplechase (a Mile race) and beat the reigning Junior champ Brian Hall: “They thought it was a flash in a pan. I wasn’t known at all. I ran another race down south, and I beat him again. Then they took notice of me.”

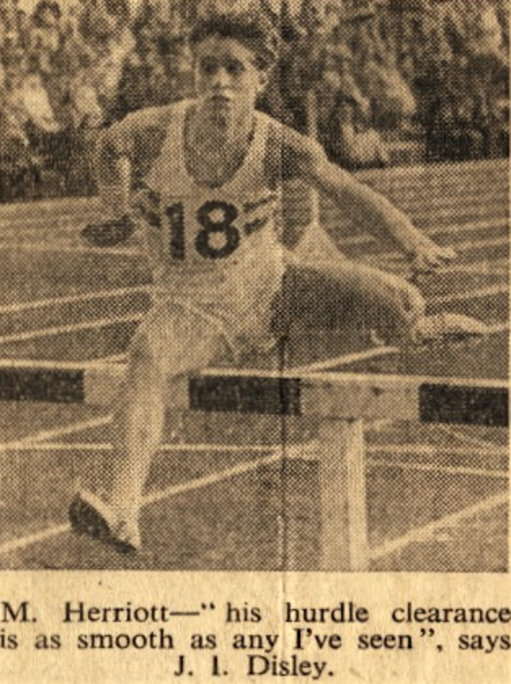

The next year, 1958, was to be his breakthrough year. In February his strength, which he had been developing gradually under Heeley’s supervision, showed great improvement when he won Midlands Youth cross-country title. Then on the track he won the British Junior 1,500 Steeplechase title in 4:20.7 and was later voted British Junior Champion of Year. Recognition from the top British steeplechasers came when Olympians John Disley and Eric Shirley invited him to run as a guest runner in the London v Prague match at the White City. He went on to become the first Junior to ever run under 9:00 for the 3,000 Steeplechase and was also selected for his first Senior international in September against Finland. Although he was last in the four-man race, he impressed with a fine 9:00.4, less than one second behind the second-string Finn. The 18-year-old had arrived on the international scene.

Training

What was the training that had brought him to international status in 1958? Tom Heeley, who had nurtured Herriott’s talent so carefully in his early years, had gradually built him up to a three-times-a-day regimen. His first session was a jog along the towpaths to work. He did this in boots—a definite influence of Emil Zatopek, who had famously trained in army boots ten years earlier. After working on the assembly line from 7:30 to 12:30, Herriott had an hour’s break for lunch. At this time he would do his second session under the supervision of Heeley (who worked as a panel beater nearby). There would always be some hurdling in this session. The third and final session was done immediately after his 1:30 to 5:30 shift so that he would have some time of his own in the evening. Again, Heeley would supervise this workout.

According to Herriott, Heeley was not a "mileage man.” He used interval training and emphasized quality over quantity. Another important aspect of Herriott’s training was the avoidance of road running. This avoidance of hard surfaces meant he escaped injury. Beyond Heeley’s careful and thorough coaching, Herriott also credits the influence of two other contemporaries, Ron Hill and Basil Heatley. “I served my apprenticeship with Basil,” he says. Heatley says he feels honoured that Herriott should speak of him in this way: “I can only assume that, as a younger runner sharing the roads, fields and dressing rooms, he absorbed aspects of my mental and physical attitude, as I did with athletes such as Gordon Pirie and Frank Sando.” (Basil Heatley, Email, Nov. 6, 2013)

1959 Season

|

At the end of the 1950s, the glory days of British steeplechasing were waning. Chris Brasher, the reigning Olympic champion, had retired. And John Disley (6th in the Olympics) and Eric Shirley (8th) were nearing the end of their distinguished careers. Now suddenly a new prospect had appeared to carry on the tradition. The 1959 season saw the 19-year-old Maurice Herriott start to fulfill that promise, as he began to compete regularly on the international scene.

At this point a word should be said about the format used in international competition at this time. There were no big meets like the Oslo Bislett Games and the Weltklasse Zürich. Instead there were international matches between two (sometimes three) countries, in which each country fielded two competitors per event. Points were won in each event--5,3,2,1—so competition was the essence of these matches; times were not important. Obviously, tactics were primary in the distance races: “We learned to race; we weren’t worrying about pacemakers, or anything like that.” Herriott believes that his experience in many of these international matches helped him in the big championships.

Herriott’s 1959 season began well with a 9:00 win in an International B competition against Norway. Then in July he won his first national title at the AAA Championships with a 8:52.8 PB. The Times Correspondent noted his “nice judgment and reasonable technique.” (Times, July 13, 1959). As British champion, Herriott was now chosen for four major international matches against top European countries. While never winning, in three of the races he pushed far more experienced runners all the way to the tape. His first race again West Germany was against Heinz Laufer, who had been 4th in the 1956 Olympics. Herriott gave him a great race, leading over the last water jump but losing out in the final sprint 9:00.2 to 9:00.8.

He faced an even tougher opponent in the next match—European 5,000 and 10,000 champion Krzyszkowiak of Poland. As the Times correspondent described it, “Herriott hung on manfully, but the last water jump found him land heavily and a good clearance of the last hurdle could not bring him near to the victor.” (Times, August 17, 1959) Second again, but this time with a big PB of 8:48.6. Next up was an international in Russia, where he was 3rd in 8:51.6, some five seconds behind the Russians Rzhischin and Ryepin. Finally he had another big battle for first with Virtanen of Finland. As the Times reported, Herriott “determinedly held [Virtanen] off round the first turn [of the last lap] and fought back furiously when he was passed on the middle of the back straight, but Virtanen was still too fast on the run-in.” (Times, Sept. 14, 1959)

So in 1959 Herriott established himself as Britain’s top steeplechaser, lowered his PB by eleven seconds, and showed himself to be a fierce and dependable competitor. A common theme emerges in the eye-witness reports of Neil Allen, the Times correspondent. Herriott was a determined competitor; in all but one of his international races he pushed his more experienced opponents to their limits. And this competitiveness and dependability were to be the hallmarks of his long international career. He could always be relied on to perform well for his country.

It was at this time that National Coach Lionel Pugh showed an interest in coaching Herriott: “He said to [Tom Heeley], ‘It’s all very well getting an athlete to win the AAA for the first time, but can you keep him there?’ Pugh wanted to take over from Heeley as Herriott’s coach: “Tom said to me, ‘If you want to go to Lionel, it’s fine with me. There will be no hard feelings.’ I said that I would pack up running rather than be coached by someone else. I just wanted to do it with Tom.”

1960 Olympic Year

After another winter’s hard work with Tom Heeley (“The training I was doing was pretty severe”), Herriott was in fine fettle going into the 1960 track season. His first major race, a victory against Italy in 8:53.2 augured well. But a minor setback in the AAA championships put some doubt in the Olympic selectors’ minds, despite the fact that he ran with a mouth abscess and was advised by a doctor not to compete. Despite qualifying for the team, he did not go to the Olympics: “Jack Crump and Harold Abrahams, in their wisdom, thought I was too young to go.” Did this upset him? “I was mortified. I didn’t think I’d have another chance. Tom thought I would have had a better chance of winning in Rome than in Tokyo. He thought I was in such good condition.”

Back to the International Circuit

After a disappointing Olympic year, Herriott bounced back in 1961, winning the British title by seven seconds in 8:53.6 and ranking 12th in the world with a new PB of 8:42.0. He ran in five international matches and won three. Perhaps his best win was against West Germany’s Boehme, where he took the lead with 300 to go and broke the German at the water jump. His last lap was an impressive 61.4. His 8:42.0 PB came in a match again the USSR, but his fast time only earned him third place. In this race, he was up against two much faster steeplechasers. Nevertheless, he stayed with them into the final lap and was only 1.4 seconds behind the winner Sokolov, who had come into the race with a season’s best of 8:34.4. Herriott, with a new 4.4-second PB, was now only 0.8 of a second outside Brasher’s British record set in the 1956 Olympics.

1962 European and Commonwealth Championships

After his Olympic disappointment, Herriott looked forward to two major games in 1962. His season started well with wins in the British Games (8:48.4) and the AAA’s (8:43.8). A loss to Poland’s Chromik, an 8:35 steeplechaser, wasn’t a disappointment, and he lined up for the European heats with great hopes. He got through the heats successfully but banged his left knee so badly on a hurdle that he was unable to run in the final. And although he couldn’t have expected to beat Roelants, who ran 8:32.6, he could reasonably have expected to be in the medals, the times for the silver and bronze medals being 8:37.6 and 8:40.6.

Still he had three months to recover, and he was definitely fit for the Commonwealth Games at Perth in December. There he was surprised by a fine run by Trevor Vincent of Australia in the final. With a hurdling style said to be even better than Herriott’s the Aussie broke Herriott in the last half mile to win by 1.6 seconds, 8:43.4 to 8:45.0. Reporters reckoned that the 36-degree heat took a lot of time out of the runners, perhaps as much as ten seconds, so Herriott’s silver medal must be considered a fine achievement.

Olympics Ahead

|

With a Commonwealth silver medal in his pocket, Herriott now looked ahead to Tokyo in 1964. And his performances in 1963 boded well for another medal there. After running a solid 17th in the highly competitive National Cross-Country Championships, Herriott enjoyed his best ever season, winning both the British Games and the AAAs. Then in July he finally beat the UK record with 8:40.4 to win in a match against the USA. More wins were to come: he was first against West Germany in 8:48.6 and first again against Sweden with another UK record of 8:36.6. But his best race was at the end of September in a match in Volgograd against the USSR. Here Herriott beat the fine Russian Sokolov with another UK record of 8:36.2. He had to run a last lap of 59.7 to beat the 8:32 performer. Thus 1963 saw Herriott really excel as a competitor. The only time he was beaten was at Helsinki, where he came up against the great Belgian Roelants—and lost to him by 4.4 seconds.

It was unfortunate for Herriott to come on the international scene at the same time as the greatest steeplechaser in the history of the event. Roelants had surprised everyone with a fourth place in the 1960 Olympic Steeplechase. Even though he had appeared in the 1959 world rankings, he had been a full eight seconds slower than Herriott, who had broken 9:00 for the first time that year. But while the Belgian authorities selected him to run in Rome, Herriott was considered too inexperienced. So Herriott stayed home, and Roelants qualified for the Olympic final, ran with the leaders and finished a creditable fourth. From that time Roelants went on to establish himself as the clear favorite for the Tokyo title, especially after being the first man to break the 8:30 barrier in 1963.

Tokyo Preparation

Herriott’s 1963-4 winter conditioning went well: “It was going to be a long season, but Tom worked it to perfection as he always did. The training was the same as before but with less recovery. Tom was a believer in a very short recovery: quarters in 66 with just 25 seconds recovery. Six 800s with just a minute’s rest in between. Savage! He was very strict over a minimum recovery.” Herriott soon found that his flat speed had improved: “I did a couple of 2- Mile races and managed to beat Rushmer and Tulloh. Tulloh reckoned he could outsprint anybody at the end of a race. I wouldn’t have that. I only beat him once, but that gave me a boost.”

Herriott started his steeplechase competition with a comfortable 8:43.8 victory and went on to win the AAA’s with a championship record of 8:40. The Times acknowledged his win: “He hurdled with his usual economy and ran with the quiet competence masking determination that has always marked his career.” (Times, July 13, 1964) Herriott followed his sixth national title in seven years with two convincing international wins against Finland and Poland (8:41.8, 8:38.0). Then in a match against France he faced one of his main Tokyo rivals, Guy Texereau, who at that time had the world’s second fastest time in 1964. Herriott was passed by the Frenchman with 300 to go, but he responded well “with a superb clearance of the water jump and last hurdle.” (Times, Sept. 14, 1964) A last lap of 60.9 gave Herriott a 1.8-second victory with 8:42.0. It was a good final race before the Olympics in October.

With a season’s best of 8:38, Herriott went to Tokyo as the seventh-fastest steeplechaser for that year. Roelants was the fastest with 8:31.8 and the five others had run 8:35+. All six of the Track & Field News journalists chose Roelants to win. Two chose Herriott for second and three for third. So despite his relatively slow 8:38 time, the experts clearly appreciated his strong competitive record and reliability.

Tokyo Silver

Two of the three Steeplechase heats were extremely competitive. Running in the second heat, Herriott needed to beak the Olympic record of 8:34.2 to win his heat and qualify. His 8:33.0 was a PB and was only 1.6 faster than the time he needed to get through to the final. His Olympic record lasted only a few minutes as Aleksiejunas of the USSR clocked 8:31.8 to win the third heat.

But all was not well with Herriott. In a filmed interview, he has explained how much his legs were hurting before the final. (manxathletics.com/2012/MauriceHerriott2012) He felt he couldn’t get high enough to clear the hurdles. It took some help from British coach Dennis Watts to get him properly prepared for the final: “Dennis Watts was tremendous. When I went on trips and was away from Tom, Dennis Watts would always be there.”

In the final, the Russian Aleksiejunas, the winner of Heat 3, led from the gun. But soon Roelants took over and was 5m ahead after one lap. At 1,000 Herriott (2:53.2) led the pack behind Roelants (2:52.0). Soon after this, Roelants burst away and only Texereau went with him. Herriott, of course, saw what was happening: “[Roelants] put in some awesome laps and opened a gap.” Herriott couldn’t respond. At 2K Roelants (5:38.6) led Texereau (5:40.4) and George Young (5:42.0), having run the second K in a very fast 2:46.6 (8:20 pace). Herriott (5:44.0) was back in 7th.

A lap later Texereau was passed by Young, but Roelants’ lead had increased to almost 40m. Now Herriott moved ahead of the pack and began to close not only on Young but also on Roelants. With 200 to go, he passed Young and started to make huge inroads into Roelants’ lead. But Roelants had enough to hold on, running the last K in 2:52.2 for an 8:30.8 victory. Herriott was just 1.6 seconds behind at the end, finishing with a 2:48.4 last K for another PB of 8:32.4. He was well clear of the third-place Russian Belayev (8:33.8).

He had run consecutive PBs in the heats and final, with his final time becoming a career best. What more could you ask of an athlete than to run a lifetime best in the Olympics? Well, some people were not satisfied: “I’ll tell you who complained after the final: David Coleman [BBC sports commentator]. I was absolutely mortified that I got a ticking off from him. And then Chris Brasher. I was a bit gutted after that. Many years later, David Coleman said to me: ‘Do you remember the time I ticked you off. I wouldn’t dare do that nowadays!’” Clearly Brasher and Coleman believed that Herriott should have matched Roelants’ early surge. But Herriott hadn’t believed he could or should chase the Belgian. Guy Texereau, a Frenchman whose ability was similar to Herriott’s, did try to stay with Roelants, but he finished a disappointing 6th. Knowing the type of runner he was—a fast finisher—Herriott was surely right not to “go for broke” early on.

After the final, over a beer, Roelants told Herriott that he had been worried about the Herriott kick and that this worry had led to his tactic of running a fast middle K. “I knew I had to break you in the middle,” he told Herriott. (Doug Gillon, Herald Scotland, Oct. 27, 2012) And Herriott acknowledges that this tactic worked: “That middle bit that Roelants ran did hurt me. He was struggling on the last lap, but I couldn’t have gone any earlier. I couldn’t have gone any faster.”

Herriott returned home an Olympic hero, but he was also a worried man: “After Tokyo, I though I was going to get the sack. I don’t normally talk to the press, but they were all around me. They asked me about BSA, my employer. I said BSA looked after me really well with time off. (Travel took longer in those days, so sometimes I was away for weeks.) I told them that BSA gave me the time off but didn’t pay me for that time. When I got back I was called in to the big management. They had no idea I wasn’t being paid when I was away competing. If I didn’t clock in; I didn’t get paid. After that I did. When I was away, the managing director sent my wages to my wife.”

Back to International Races

|

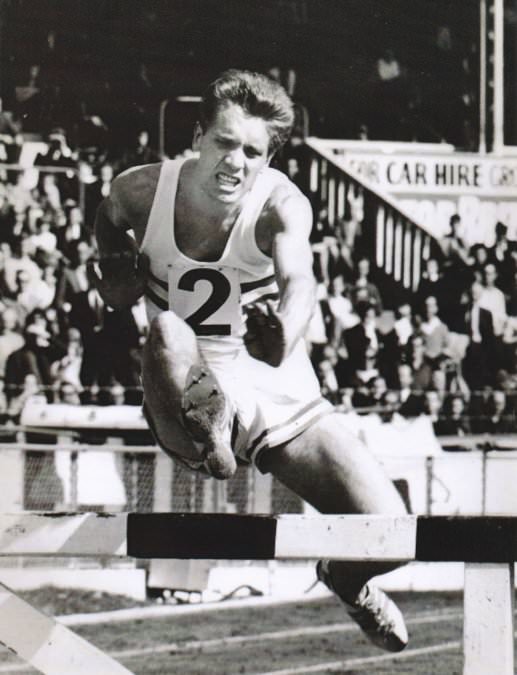

| 1963. Herriott on his way to a nationalrecord of 8:36.2 in a match against Sweden. |

After a short indoor tour of the USA, Herriott prepared for the 1965 season that would involve several international races and the European Cup team competition. He started competition with his sixth national title in 8:41 and a victory at the Helsinki World Games (8:48.8). Then he prepared for the international matches: “In those days, if you were selected for an international, you didn’t dare say no.” In the tactical four-man races, it was important to have a partner who could give both emotional and tactical support: “I had a good partner for ten years, Ernie Pomfret. We never had any agreements, except that we would never leave each other in the lead for more than a lap or two without giving help. We had to get points, so we worked as a team.” Pomfret never beat Herriott, but with a fine 8:37 PB, he was able to give valuable support. Did Herriott find that his experience of these four-man races helped him tactically when he came to major championships? “Absolutely. We learned to race; we weren’t worrying about pacemaker, or anything like that.”

Perhaps 1965 was Herriott’s most successful year for international races. He ran four times—against Hungary, Poland, East Germany and West Germany—winning each time. With an excellent ability to put in a fast last lap, he was virtually unbeatable, although his season’s best was only eighth fastest in the world. Perhaps his best race was in the European Cup semi-final, where he was up against the top steeplechasers from five other European countries. With a last lap of 61.2, he was again a winner. The Times correspondent reported his performance with unusual enthusiasm: “It will be a long time before I forget the intelligent way in which Herriott handled his talented opposition…. With two laps to go, he was two yards down on the Rumanian, Vamos, who has run much faster on the flat, but Herriott, not doubt noticing the Rumanian’s ragged hurdling, took him on the back straight hurdle on the last lap, exploded out of the water jump and so had a safe enough margin in the straight to play with when both Vamos and Persson, of Sweden, came back at him.” (Times, August 23, 1965) Herriott’s only loss of the season was in the European Cup final when he was beaten by a 21-year-old Russian, Kudinsky, who showed real speed in the last 50 yards to gain a one-second advantage, 8:41.2 to 8:42.2. Herriott reckoned he had run well but now admits, “It was very dodgy, that one.”

Recognition of Herriott’s huge contribution to British athletics came in 1965, when he was made British Team Captain. “I was quite humbled by that,” he recalls.

1966 Commonwealth and European Games

Although he won the British title yet again with a new championship record of 8:37.0, Herriott didn’t have such a successful year in 1966. In June he was beaten into third in an international match against the USSR, even though running his best time of the year (8:32.8). And he managed only 8th in the European Championships (8:37.0 behind winner Kudinsky’s 8:26.6). He remembers this being a tough race where he was "dusted up" by some rough-house tactics by the Russians. Following the European championships, he was beaten by Texereau (8:43.4 to 8:45.6) after losing contact with two laps to go.

But he ran better in the Commonwealth Games in Jamaica. Just before the Games he impressed the great Kip Keino, who watched him do one of Tom Heeley’s interval sessions: “Keino told me that he thought Tom’s sessions were very good. He actually did one of them himself. He watched me do it and said to me ‘That was very good, Maurice.’ He then did the same session, but in a track suit--in the humid heat of Jamaica! It meant a lot to me that he was watching [my session]. I can remember the session to this day; it was 12x440 under 60 with 25 seconds rest in between.”

The Commonwealth Steeplechase final (“It was very hot and humid.”) was a surprisingly fast race with the first three finishers posting huge PBs by margins of 11.8, 13.6 and 14.4. There were four together at the bell with Herriott, the favorite, tracking Peter Welsh, Kerry O’Brien and Benjamin Kogo. Welsh, who had done some of the pacemaking, took the lead at the hurdle before the last water jump and managed to hold off the other three to win by 2.8 seconds. O’Brien and Kogo also finished ahead of Herriott, who nevertheless ran only 0.8 outside his PB with 8:33.2. His fourth place was a disappointment: . “It was just a blanket finish. I drew the straw for fourth. I was disappointed I didn’t get a medal. I didn’t run badly at all; I was just outsprinted.” Still, there was the 1968 Olympics to look forward to.

1967 Season

Herriott had by now reigned so long as Britain’s premier steeplechaser, that it was quite a story when, in May 1967, he finally lost a steeplechase race to a 25-year-old compatriot, John Jackson, 8:36.4 to 8:40. In fact it was his first defeat by a fellow Briton since 1960. But this did not mean that he was in decline. He went on to win his seventh national title in June and the next month ran a very fast 8:33.0 in a match against Hungary and West Germany. But despite running his fastest time of the year, he was unable to beat the Hungarian Joni (8:32.6), who took him at the water jump.

The rest of his 1967 season was not so successful as he was beaten by Luers of West Germany (8:41.6 to 8:45) and then by the American Traynor, albeit after a hasty transatlantic flight from Montreal.

Mexico Fiasco

In what was to be his last year of competition, Herriott finished only third (8:39.2) in the AAA’s title race. However, the Olympics were three months away. A sixth-place finish in Duisberg suggested he was in good form, if not top form by September. In fact his season’s best before the Olympics ranked him only 20th in the world and placed him 12.6 seconds behind the world leader, Viktor Kudinsky. But the main problem was that he had been unable to do any altitude training for Mexico City. He had gone to high-altitude Fort Romeu with the British team, but some problems there meant that the team stayed only three days. So he arrived in Mexico City with virtually no altitude conditioning: “I was just naïve. I didn’t imagine it was as bad as it was.”

Herriott finished back in eighth place in his Olympic heat with 9:33, more than a minute slower than his PB. He was carried off on a stretcher, given oxygen and sedated, and didn’t recover consciousness for two hours. Even the next day he needed assistance walking. “They had to get me down very quickly to sea level at Acapulco,” he told Doug Gillon. “I remember nothing from the start [of the race]. The hurdles were a blur. I can’t remember a single one. When I finally came round, I asked about all the bandages on my ankles and knees. It was where I had clouted the hurdles, and that wasn’t [like] me. I trained over hurdles every day, but hadn’t the strength to lift my body to clear them.” (Herald Scotland, Oct. 27, 2012) As the Sports Illustrated report put it, “He had waited four years since Tokyo for this mockery of a second chance.” (SI, Nov.11, 1968)

Herriott’s long career was over: “I retired after that, but I had promised my wife Marina that I would retire after Mexico. I did carry on for one more year at club and county level. I did one more steeple as a time-trial; I ran about 8:45.”

Herriott, now 74, still lives with the legacy of that Mexico race: “I’ve still got spots on my lungs. Every time I have an x-ray, they notice a slight shadow on my lungs.” These shadows were caused by oxygen deprivation. “I nearly died at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico,” he says today.

Not long after his retirement, Herriott’s job in Birmingham disappeared when BSA closed down. This led to the Herriott family moving to the Isle of Man, where he found a job on a trawler. He spent 15 happy years working at sea and then found a job on land running a paper recycling operation. After another 15 years in this job, Herriott retired again. He still lives on the Isle of Man.

Overview

|

Herriott’s athletic career has many notable features. Not least was his consistency; he was ranked in the world’s top 50 for ten consecutive years (1959 to 1968). Though never focusing on fast times, he still ranked in the top six in the world for five of those ten years.

It was as a competitor that Herriott really shone. He won the British Steeplechase title eight times, and won his event in countless international matches, once winning ten of twelve consecutive races. Then, of course, he won Olympic and a Commonwealth silver medals. When interviewed, he frequently referred to the camaraderie of the British team in the 1960s: “That camaraderie means a lot to me, and it meant a great deal to me at the time. I’ve appreciated it more as the years go by.” This begged the question as to whether, looking back 45 years, he now valued this camaraderie more than his competitive successes. But he denied this: “The medals are lovely.”

Through dedication and hard work, Herriott managed to defeat many more talented runners. And he could always be relied on to perform well. The respect he earned from his British team-mates was shown in his being chosen as team captain. Former team-mate Basil Heatley calls Herriott “a gentleman par excellence,” adding that he was “justifiably one of the most popular members of the GB athletics team of my era.” (Email, Nov.6, 2013) The Times correspondent Neil Allen, who spent many years with the British team, got it exactly right when he called Maurice Herriott an athlete’s athlete.

Note: All unattributed quotes are from a phone interview with Maurice Herriott on October 9, 2013.

13 Comments