Profile: Herb Elliott

b. 1938

The bare facts of Herb Elliott’s career say it all: unbeaten over One Mile and 1,500; Olympic 1,500 champion in WR time; and Empire Games double champion. He was one of the greatest runners of the twentieth century.

Something of the unique character of this man can be shown in my sole encounter with him. He had committed to run an 880 in my home town of Brighton. However, he was completely out of shape, not having run for weeks. Nevertheless, he still turned up and ran his guts out—literally. He was violently sick afterwards. His time was a mundane 1:55, but he had honored his commitment and given his best. Once he had recovered I approached him for an autograph in his book The Golden Mile. He signed it with pencil, and in response to my comment that I had enjoyed the book, claimed that he hadn’t read it. Modesty, perhaps false modesty, but still modesty.

Herb Elliott always gave the impression that running was not that important to him. Yet he trained ferociously at times and was a merciless competitor--merciless toward himself as well as towards the other competitors. Yet there was always a balance in his life between his running and everyday living. He practiced religion, married his childhood sweetheart early, took care to get educated and knew how to relax socially. “I needed releases,” he told Jim Denison, “and I was never afraid to have a break.” (Denison, Bannister and Beyond, p.59)

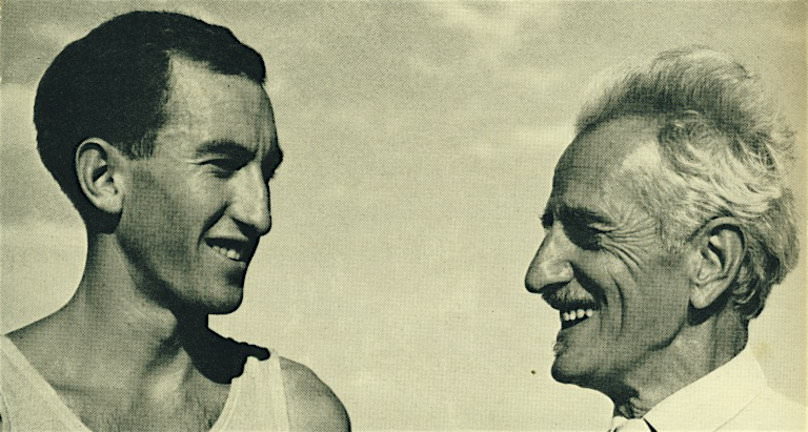

|

| Elliott with Percy Cerutty. |

There were two formative events in his teens that set him on his path to running immortality. First, he met Percy Cerutty, a flamboyant but at that time relatively unproven running coach. Second, he witnessed the awe-inspiring 5,000 and 10,000 victories of Vladimir Kuts in the Melbourne Olympics.

Elliott met Cerutty in 1955: “It was just one of those peculiar tricks of fate that I met Percy and certainly his contribution to my development as a champion athlete was an invaluable and integral part of it. It wouldn’t have happened without him.” (Amanda Smith, TSF, ABC Radio) And Cerutty’s impact was immediate. “From the first time I met Percy, he excited me as a person,” Elliott told Brian Lenton. “I’m not sure whether it was a blending of personalities or minds, but the way he spoke appealed to me. I could feel it stir ambitions in me that must have been already there somewhere.” (Lenton, Brian Lenton Interviews) Many runners, like John Landy and Ron Clarke, were put off by Cerutty’s eccentric and sometimes abrasive ways. But Elliott was able to deal with him: “I always respected, listened to, learned from and loved Percy.” (Lenton)

The second formative event for Elliott, Kuts’ running in the Melbourne Olympics, was what Elliott called the “final link in the chain” in his decision to “give it a go.” (Lenton) Already inspired from meeting Cerutty, Elliott said that Kuts’ achievement clinched it: “The aggressive way in which Kuts dealt with Gordon Pirie in the 10,000 affected me tremendously.” (Lenton)

Born and brought up in Perth, Western Australia, Elliott had shown great promise before he met Cerutty. He was first seen by Cerutty winning a Mile in 4:22. An impressed Cerutty asked to meet the 17-year-old schoolboy and was invited to the Elliott family home in Perth for dinner. At this meeting he said to Elliott: “There’s not a shadow of doubt that within two years you will run a Mile in four minutes.” (Elliott, The Golden Mile, p.26)

Elliott next met Cerutty when his father took him to Melbourne for the Olympics. After a three-hour meeting, Elliott wanted to stay in Melbourne to train with Cerutty. His parents gave him their blessing, and the next week he was trying to keep up with Murray Halberg at Cerutty’s Portsea training camp. Elliott relished the routine at Portsea: a 7am run, outdoor activity like swimming in the morning, a session at the Portsea oval at noon, a siesta, weight training at 4, and a long run at 5. “It was demanding, incredibly so, Elliott recalled. “But also inspirational, natural and beautiful.” (Denison, p.59)

All the while he was absorbing Cerutty’s ideas. “He was never terribly interested in what I was doing in my training," Elliott recalled. "He was more interested in my state of mind.” (Denison, p.66)

Elliott’s improvement was meteoric. On January 12, 1957, Elliott, angry at being put in a B race, ran the Mile in 4:06, a Junior WR. At the end of that month he ran the same time to win the Victoria Championships. Soon after he ran an 880 Junior WR with a 1:50.8. After another two 4:06 runs, he improved to 4:04.4. Then at the end of the Australian season he came up against the experienced Olympian Merv Lincoln in the national championships. Stampfl-coached Lincoln led at 4:00 pace until Elliott sped past just before the bell and held on to win in 4:00.4. Cerutty’s prophecy in Perth had come true.

After six months with Cerutty, Elliott went home to Perth for the off-season. He trained hard over the Australian winter before returning to Melbourne in August of 1957. He was clearly in good shape, knocking 17 seconds off his best on the famous Hall Circuit at Portsea. And in January 1958 he became the youngest runner to beat 4:00 for the mile with 3:59.9. Then he had two races against Lincoln, who had already clocked 3:58.9 that season. Herb won both in under 4:00, although in the second race Lincoln was so close that both runners were both timed at 3:59.6. The Australian press built up this developing rivalry, portraying it as a feud between coaches Cerutty and Stampfl. Elliott’s training also contrasted with Lincoln’s track-based and closely timed sessions: “I had a genuine sympathy for Merv. While he was plodding his way through [monotonous training sessions], I was galloping over sand-hills…and splashing through the surf, or frolicking in the beautiful Botanical Gardens.” (Elliott, p.70)

|

| On his way to his first 1,500 WR. Halberg, Rozsavolgyi, Waern Ibbotson in his wake. |

After winning two national titles, Elliott was named for the Australian 1958 Empire Games team in both 880 and Mile. First, he made a successful but tiring and somewhat distracting American tour. Next Elliott was soundly beaten over 880 by Brian Hewson and Mike Rawson on arriving in London. It was a wake-up call. When the Empire Games came round, Elliott was ready. He jumped Hewson at the bell to win the 880 and then completely dominated the Mile--two gold medals in his first major games. But the best was yet to come. In Dublin he decimated the Mile WR by 2.7 seconds with 3:54.5 (See Great Races # 12). Then he went on to run against Europe’s best and broke the 1,500 WR in Gothenburg with 3:36.0. He followed this with a 3:37.4 1,500 and a 3:55.4 Mile to complete an unbelievable season.

It was during his European tour that Elliott was offered $250,000 to turn pro by an American promoter. This was an astounding offer; Herb’s father thought it was $25,000 because he couldn’t believe the offer was so high. After long negotiations, however, Elliott decided to remain amateur. This episode distracted him from running, as did his marriage to Anne in May 1959. He also accepted a three-year scholarship to study science at Cambridge University from October 1960.

But the Rome Olympics still loomed large for him. An Olympic victory would be the perfect conclusion to his running career. But he first needed rest as he had endured a very long season in 1958, from January races in Australia to the European season ending in September. A long rest was followed by a quiet 1959, when he ran only once under 4:00 and stayed in Australia. A lot of his time was spent on “studies, marriage and rustling a home together.” (Elliott, p.129)

Then the work for Rome began: “On 26th December I stopped smoking and started serious training at Portsea.” (Elliott, p.130) He started with some low-key races over 880, 1,000 and 3,000. His first Mile was run in 3:59.8; then he ran 4:00. Both were run in February. In the March Australian Championships he won the Mile in 4:02 and the 880 in 1:50.1.

Before he left for the USA in May, he ran a 33-mile training run, believing that “the discomfort of a Mile or 1,500 metres race is more easily born if measured against the suffering…in a torturing 33 miles.” (Elliott, p.144) On the USA tour, he beat both Tabori over 1,500 in 3:45.4 and Grelle in Compton with a 3:59.2 Mile. Then it was back to Melbourne to train for the September Olympics. During his preparation he was buoyed by a time-trial over the Hall Circuit where he beat his best by over 7 seconds.

|

| Elliott in his prime. His physique showsthe benefits of weight training. |

In Rome, Herb won his heat in 3:41.4: “I was elated,” he wrote later. “The lack of confidence resulting from lack of top-class competition in the previous weeks vanished.” (Elliott, p.171) At the start of the final, Herb settled comfortably into 5th place. He was feeling tired and thought he was breathing too hard. This forced him to consider postponing his planned break. But when the time came just after 800, he began his move up. He passed the leader Bernard with just over 500 to go. As he entered the straight he hit the wind. He led at the bell and pushed on.

Cerutty had said he would wave a towel on the back straight if Elliott was on WR pace. And Elliott saw the white towel and sprinted for all he was worth over the last 200. At the tape he had a convincing 20-meter lead and a new WR of 3:35.6. He was Olympic champion. As he was leaving the stadium after receiving his gold medal, Elliott was approached by a fair-haired man who spoke with a thick accent, “It was a wonderful run.” The man was Vladimir Kuts, who had been Elliott’s inspiration at the previous Olympics.

Elliott was due to start his Cambridge education in October, but first he made use of his running form, racing 11 times in 19 days. He ran four four-minute miles, the fastest being 3:57.0. He ran 3:38.4 for 1,500, as well as racing over 880 and 1,000. But he found it all an anti-climax after his great Olympic run.

His running career was really over after his European tour, although he did run for Cambridge University at a low-key level. The most interesting aspect of this last chapter of his career was his narrow escape from losing his all-time unbeaten streak over the Mile. A very talented Martin Heath pushed him to the very limit in a varsity race. But Elliott could always find a little extra when it really counted.

17 Comments