Bill Bonthron Profile

1912-1983

With his talents, American miler Bill Bonthron could have conquered the world. He had strength, speed and a tenacious competitive drive. But while he performed brilliantly in his own country and even set a world record for 1,500 in 1934, he made little impact on the international scene and never competed in an Olympic Games.

|

Following the traditional amateur conventions of his time, Bonthron planned his athletic career for just the four years of his university education. Once he graduated and married, his priority was his job as an accountant and he announced his retirement from running in 1934. Although he later broke with convention and continued to train seriously in his spare time, he never regained the form of his university years and failed to qualify for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He did make one European tour in his graduating year, but failed to live up to the reputation that had crossed the Atlantic before his arrival.

That reputation was established during 1933 and 1934, his last two years of competition as a university student. After thrilling the indoor crowds in 1933 with some brilliant relay anchor legs and winning the 800 and 1,500 collegiate titles outdoors, he ran under the Mile world record with 4:08.7, finishing second to Lovelock, who ran 4:07.6. The next year, in one of many thrilling races with Glenn Cunningham, he set an indoor 1,500 world record behind Cunningham, both of them clocking 3:52.3. Later, on his own, he set a new outdoor world record (3:48.9) in the AAU championships.

---

Bill Bonthron was born into a Scottish immigrant family that had arrived in Canada in 1855. His father had gone to the Yukon during the gold rush and had become a bookkeeper for those lucky enough to find gold. He then took his accounting skills to Detroit and eventually became a partner in the prestigious Price Waterhouse firm. Bill grew up in Detroit. His childhood was seriously affected by a tree-climbing accident. One of his legs was severely burned when he fell on a 6,600-volt wire. “They say my rubber-soled shoes helped,” he told The Boston Post years later. “My weight broke the contact with the wire and dropped me some 30 feet to the ground. They had to graft skin over my burns because electric burns do not heal by themselves.” (February 12, 1934) He was scarred for life, but his leg regained its strength through therapeutic walking and running.

Although he was more interested in playing football and baseball, this burn therapy introduced him to competitive running. At middle school he ran 440, 880 and Mile and managed a fourth place in the Detroit school championships. Then at high school he excelled at running with a 4:35 Mile and a 2:05.6 880 in his graduation year.

Harrier

Entering Princeton in 1930, Bonthron was hoping to make the freshman football team. But Keene Fitzpatrick, the head track coach, managed to persuade him to change his sport to track. Working under Assistant Coach Matty Geis, he immediately became one of two stars on the freshman cross-country team with Ed Read. The two won four races that season, always finishing together. In 1931 the duo had similar success, after which Read dropped out of college. So for his first two years at Princeton Bonthron was primarily a cross-country runner. In his third cross-country season he was almost unbeatable. After winning the Princeton title by 40 seconds, he won the big match against Yale. His only downfall was the IC4A meet when, despite being one of the favorites, he finished 46th. His cross-country strength later earned him second place in the IC4A Two Miles. This track success concluded his 1932 season; there were no thoughts about the Olympics later that summer.

Track Runner

|

| Typical Bonthron finish in his college days, coming though on the outside. |

Bonthron, so far noted for his cross-country strength, began to show track speed in the 1933 indoor season. Unusually for a cross-country runner, he had been training in the gym with weights and the medicine ball. Perhaps this conditioning helped him to a new level on the track, for he quickly became celebrated for dynamic anchor legs in the relays that were an essential part of the American indoor meets. He also ran some fast times. In a 2,950m relay at the AAU indoor championships he ran the 1,500 anchor leg in 3:53.4, two seconds faster than the winning time of the open 1,500 race won by Venzke. It wasn’t just the fast time that impressed the New York fans. They appreciated the way he had made up ground and then roared to victory in the stretch. “That takes spirit as well as speed,” said The New York Times, “and apparently Bonthron has both.” (February 15, 1933)

His track form continued in the outdoors. In the Penn Relays, in helping Princeton to win a medley relay he ran a 1:54.5 800, moving from 4th to first with what The New York Times called “a superb finish.” (April 29, 1933) Against Cornell he won the 1,500 by 30m in 3: 55.5. He was also running multiple races in some collegiate meets. Against Yale he won three races in one day: 800 in 1:53.4, 1,500 in 4:01.3, 3,000 in 8:53.8. Then in the IC4A Championships he achieved the first double since 1912, winning the 1,500 in 3:54.0 and then the 800 in 1:53.5.

|

This string of high-level performances attracted a lot of national media attention, and the “black-haired, barrel-chested Bonthron” was their main focus for the upcoming July match that pitted Princeton and Yale against Oxford and Cambridge, and Bonthron against 1932 Olympic finalist Jack Lovelock in the Mile.

How had this 20-year-old American from Detroit reached world-class status so quickly? Full credit must go to his coach Matty Geis who took over as Princeton’s cross-country coach in 1930 and as head coach in 1932. Geis, a former middle-distance runner, had first developed Bonthron’s strength with a lot of cross-country running. He must be credited for Bonthron’s ability to recover so well that he could race well two or three times in an afternoon. Geis has left no material on his training methods. Only Lynn McConnell has found any information on Bonthron’s training; it came from an interview with Jim Bonthron, Bill’s son: “He used to run eight round-the-bend 220 yards at the end of every session, whether he had done ten miles for endurance or in-and-out 440 yards for speed.” (Conquerors of Time, p. 81) This is the only information on how Geis managed to develop Bonthron from a strength runner to a fast-finishing miler whose kick was feared by runners and admired by spectators.

Big League

|

|

Princeton 1933. With 600 to go. Bonthron takes over the lead. Lovelock follows closely.

|

Bonthron’s first major race took place on July 13 at Palmer Field, Princeton’s home track. He was eleven days past his 20th birthday. His main opponent, Jack Lovelock, was almost three years older and had placed 6th in the 1932 Olympics. The New Zealander had a PB of 4:12, but he had run only 4:18 in 1933 until the Harvard-Yale match a week earlier, when he ran 4:12.6, winning by 100 yards “without undue effort” (As if Running on Air: The Journals of Jack Lovelock, p. 198) and covering his last lap in 60 seconds. Just prior to the July 13 race he had watched Bonthron train and was impressed: “He had none of the light lissome swing of most great middle-distance athletes…he was more the Cunningham type, big, powerful, lumbering with very little pretense at an easy style, with an exaggerated shoulder and arm movement. But his leg movement was good and one always respects a powerful opponent.” (Journals, p.198) In a pre-race Mile time-trial, Bonthron had clocked 4:16, which was far superior to any of his previous Mile clockings. His time in the IC4A 1,500 six weeks earlier was equivalent to about a 4:12 Mile. Lovelock considered him capable of running 4:09, so he decided to aim for 4:08.

At the gun, Bonthron went straight to the front. Hazen, his team-mate, took over after 200 and the field went through in 61.3 and 2:03.5. Horan, Lovelock’s partner, then tried to maintain the fast pace but soon faded, leaving Bonthron in the lead. With just over 600 to go, Bonthron and Lovelock had dropped the field. Bonthron led at the bell (3:08.6) and made his effort on the back straight. Although he was able to open up a small gap initially, Lovelock was back with him on the last bend. Afterwards, Lovelock wrote in his journal, “This was where I had expected and hoped that he would try to pull away, so I was ready and waiting…. When I saw Bonthron make his big effort on the back stretch and fail to pull away, I knew I had the stuff to win.” (Journals, July 15, 1933)

|

|

First meeting with Lovelock. Bonthron pushes him to a new world record. |

Bonthron had made his move too early, especially in such a fast race. Lovelock waited till they hit the straight and then powered past convincingly. The New Zealander looked superb until he tied up in the last 20, but by then he was well clear. Bonthron’s pace in the last two laps pushed Lovelock to a new WR of 4:07.6, while Bonthron had run a huge PB of 4:08.7. The last lap was run in 58.9. Both were under Ladoumègue’s 4:09.2 world record. The conditions were good, warm and windless, but Lovelock believed the track was inferior to the Harvard one he had raced on the previous week--“hard and fast but with a slight tendency to lift.” (Journals, July 15,1933). Bonthron was quoted as saying, “I was in the best shape of my life and did about what I had hoped. I’m satisfied with my race and I’m satisfied that I was beaten by the greatest miler in the world.” (Cordner Nelson and Roberto Quercetani, The Milers, p. 83).

Just 90 minutes after his great Mile run, Bonthron lined up for 880—much to Lovelock’s incredulity. Coach Geis was against him running a second race. According to Arthur Daley of The New York Times, “There was not a person in the stands who believed that the Princetonian had a ghost of a chance against a half-miler of the superb ability of Pen Hallowell, the ex-Harvard star.” (New York Times, July 15, 1933) With 200 to go, Bonthron was ten yards behind Hallowell, but then he changed gear, caught the Oxford runner 20 yards from the tape and roared past for a 1:53 victory. The win was not only a personal success but also the crucial one in the match competition that gave Princeton and Cornell the team victory.

Lovelock was very impressed with Bonthron’s two races: “That a boy of 20 should be capable of running a 4:08.7 Mile and a 1:53 Half Mile with an hour and a half is more than phenomenal—it is almost superhuman.” (Journals, p. 102)

Meteoric is an overused word in sports writing, but it can surely be applied to Bonthron’s emergence as a world-class miler in 1933. By the start of the year, although thoroughly conditioned by three years of successful college cross-country, he had only once in 1932 shown some potential on the track. In the IC4A Two Miles he had placed second, 25 yards behind winner Joe McCluskey. As soon as he began racing indoors in 1933, his competitive flair and his exciting finishes quickly caught the imagination of both the press and the spectators. But no one had expected that he would break Ladoumègue’s world record in the summer. And significantly he had yet to race America’s two of America’s premier milers—Glenn Cunningham and Gene Venzke.

Back to the Country

The Princeton Mile on July 15 was the last race of Bonthron’s 1933 track season, but he was soon back in training for his last college cross-country season. The most ardent of team runners, he took his races very seriously. This tenacity was evident when he collapsed with cramp 40 yards from the tape in the Yale-Harvard-Princeton race. He tried to finish, but his coach physically prevented him from going farther. He was taken to hospital, where he was listed as suffering from exhaustion. Coach Geis told the press that the fast early pace had caused Bonthron to collapse. Bonthron had been leading by 300 yards at the halfway point and was a minute under the pace for a course record. After this setback he didn’t run the IC4A cross-country championships, where he would have had a good chance at the title.

Arch-Rival Cunningham

|

|

Cunningham leads Bonthron in an indoor meet. Note the dinner-jacket dress of the officials. The official on the right is telling the runners that there's six laps to go. |

Fully recovered from his collapse, he was in good shape for the 1934 indoor season. The press were looking forward to his first meeting with Cunningham, who had been unbeaten over a Mile for two years. This first-time encounter was planned for the Baxter Mile; for Bonthron it would be his first-ever indoor Mile. The media build-up for this race led to a nervous and slow start: 65 and 2:13.6. Cunningham then took charge; with Bonthron and Venzke on his heels, he injected a 62 lap. He still led at the bell, which was inaudible with 16,000 fans roaring over the three-man race. Bonthron and Venzke stayed with Cunningham on the back straight. Bonthron didn’t sprint until 50 to go, when he moved to the shoulder of Cunningham. Only in the last few strides of the race did he manage to inch ahead. Cunningham dived (some say stumbled) at the tape and fell headlong, but the lean of Bonthron just won the race. A fast-finishing Venzke was only a stride behind for third. This was indoor miling at its very best. The first two were timed at 4:14.0, meaning the last 880 was run in just over 2:00. The general post-race opinion was that Bonthron had outsmarted Cunningham, who was “still full of running” at the finish. (John Kieran, New York Times, March 10, 1934)

|

|

Cunningham holds off Bonthron to win the 1934 AAU indoor title for 1,500. Both set a new indoor world record of 3:52.2. |

A week later the three raced again in the AAU indoor 1,500. This time the pace was fast from the start, with Cunningham trying hard to negate Bonthron’s finish. Cunningham took the field through in 62.2, 2:09.4 and 3:09.6. Bonthron had kept close to Cunningham for the first half, but by 1200m Venzke was in second and Bonthron one second back. When Venzke passed Cunningham, Bonthron dropped back five yards. Only with a lap to go did Bonthron start to close the gap. When Cunningham unleashed a sprint past Venzke on the back stretch, it looked as though the race was decided, but Bonthron never gave up. He passed Venzke on the inside with 30 yards to go and along the final stretch he bore down on the tiring Cunningham. As in the previous week’s race, both lunged at the tape and both finished in the same time of 3:52.2, a new world indoor record. On this occasion it was Cunningham who got the verdict. Venzke, who was “less than a step” behind yet again, had probably helped Cunningham win the race because on the last lap Bonthron lost a little ground on Cunningham before finding a way to move past Venzke. If the race had been a little longer Bonthron would have won easily, as Cunningham was all-in at the tape.

The next major indoor race was the Collegiate IC4A, where only Bonthron and Venzke were competing. Venzke took the lead from the start. Bonthron didn’t seem concerned and ran in the pack for the early laps. After running in sixth place for the first two laps, he gradually moved through the field and on the sixth lap he had moved into second. Venzke by this time was 20 yards ahead. At 6 ½ laps this lead had increased to 25 yards; Bonthron had only three laps to catch his Pennsylvanian rival. But within two laps he was only a stride behind. On the last lap he moved into the lead and finished a stride ahead. Then while Venzke stopped, Bonthron kept going, in a vain attempt to break the 4:10 Mile record. The New York Times reported remarked on the ease with which Bonthron caught and then passed Venzke. Clearly he was in the form of his life and had no trouble beating Venzke head on. But he had taken a risk in letting Venzke get so far ahead, a habit that was sometimes his downfall.

Princeton Duties

With one win each, Bonthron and Cunningham looked ahead to the outdoor season, while the media anticipated the ultimate showdown. But for the first part of the season, Bonthron had relay duties for Princeton. It should have been a good way to sharpen his outdoor running in preparation for the big meets, but Bonthron got caught up in the intense rivalry of the team competitions and began running at least two flat-out races in each meet. In the crucial match against Harvard, he won the 1,500 (4:05.8) and the 3,000 (9:04.8) and wanted to run the 800 as well. Marty Geis had to use “all his persuasive powers and a bit of physical force” to prevent him from racing a third time. (New York Times, May 6, 1934). But Bonthron got his way against Yale and won three events (4:01, 8:58, 1:56). He followed this up with an impressive double against Cornell (3:53.7, 1:56.1).

Setback

In early May it was announced that Bonthron and Cunningham would meet over a Mile on June 16 at Princeton. This was where, the previous year, Lovelock had defeated Bonthron and set a world record of 4:07.6. Lovelock was invited to compete again, as was Italian Luigi Beccali. Before this important race Bonthron ran once more for Princeton, winning the 800 and 1,500 in the IC4A Championships. In both races he showed complete confidence in his kick, hanging back in the 800 and entering the final straight in 8th position and then in the 1,500 weaving his way through the field in the latter stages.

With his college career completed except for the NCAAs, Bonthron now faced his biggest outdoor test in the Princeton Mile. Although Lovelock and Beccali did not enter, Cunningham and Venzke were both capable of beating him. So it was a shock to his coach that Bonthron did not arrive for the race properly prepared. Of course, he was involved in graduating at this time and was due to get married soon after the race, so perhaps his mind was not fully on the race. He arrived for the race at the last minute after playing golf in the hot sun and jogging to the track from the golf course. This was no way to prepare to race the talented Venzke, yet alone Cunningham, who was unbeaten in his ten previous outdoor races. After his two IC4A victories that saw him winning by inches after staying well back, the press were starting to ask if he was becoming overconfident. It was clear that he would have to change his tactics from the cavalier manner he had raced in the college circuit.

With the temperature in the nineties, Venzke led through in 61.7. Then Cunningham, sporting a tightly taped ankle, took over with Bonthron at his heels. But the pace was not that fast in the second lap (2:05.8 at 880). It was at this point that Cunningham applied his race plan, upping the pace for a 61.8 third lap. Predictably he was trying to dull Bonthron’s famed finishing kick. Bonthron must have been prepared for this, but he began to lose ground on the backstretch and lagged by seven yards at the bell. Bonthron, clearly not 100%, lost even more ground on the final lap, while Cunningham, buoyed by his large lead, powered on with a 59.1 last lap to break Lovelock’s world record with 4:06.7. The race was succinctly described in six words: “Cunningham ran Bonthron into the ground.” (New York Times, June 16) Bonthron’s time was 4:12.5. He claimed he had trouble breathing in the heat. Had he been properly prepared for the race, who knows how fast the finishing time would have been. He had lost a golden opportunity to run a 4:05 Mile.

Comeback

This defeat was a wake-up call for Bonthron. He received some harsh criticism, especially from his coach, over his golfing before the race. And with his final exams over, he was able to prepare thoroughly for the rematch with Cunningham at the NCAA Championships in California. This time he knew he could no longer hold back and rely on his finish; he had to stick close Cunningham. He managed to do this and was perfectly positioned to blast past the ailing Cunningham with 120 yards to go. In perfect conditions he ran 4:08.9, running the last lap in 58 and leaving Cunningham a substantial 1.7 seconds behind. So powerful was Bonthron’s finish that his coach believed he had a 4:05 in him that day.

|

|

AAU 1934 1,500. Bonthron's greatest race. He passes Cunningham 30m from the tape and sets a new world record of 3:48.8. |

The Bonthron-Cunningham battle was tied again at two apiece. Now it was on to Milwaukee for the AAU 1,500 two weeks later, when their intense rivalry led to a world record in heavy warm weather (100F). After Venzke set the early pace with a 61.3 first lap, Cunningham took over and the race quickly became yet another duel with Bonthron. This time Cunningham surprised with a very fast second lap of 60.5, forcing Bonthron to slip past Venzke to keep in touch. On the third lap, Cunningham didn’t let up, and Bonthron let him go on the back straight. It turned out to be a wise decision, for Cunningham went through 1,200 in an astonishing 3:04.5, the fastest ever run in a 1,500 race. Bonthron was also fast at 3:06, but he was still running within himself.

Cunningham’s lead widened to 15 meters round the last curve; the race seemed over. But Bonthron still had a little in reserve and would not give up. He put his head down and charged after the tiring Cunningham. In the next 30 meters, the gap was halved. He finally caught Cunningham 30 yards from the tape to win by just 0.1 of a second in a new world record of 3:48.8. Cunningham clocked 3:48.9. Bonthron’s last 300 was 42.9; Cunningham’s 44.4.

This was Bonthron’s finest hour. He was under Ladoumègue’s 3:49.2 world record and also under Beccali’s as yet unratified 3:49.0. After shaking Cunningham’s hand, Bonthron disappeared into the stands and did not attend the victory ceremony. The press concluded that it was because of exhaustion, but Coach Geis later corrected this supposition: “You see, he has flat feet…. His arches are almost flat, and I take pretty good care of them. It was hot at Milwaukee, and I knew his feet would swell after the race if I didn’t get after them, so I hauled him right in, braced his arches and wrapped his feet in cold bandages. Some fellows saw him lying there and that was how the rumour spread that he had collapsed after the race. He hadn’t collapsed at all. He was in fine shape. But I kept him there to fix his feet and give him a rest.” (John Kieran, New York Times, July 9,1934)

Arthur Daley described Bonthron’s effort as “one of the most devastating finishes ever seen.” (New York Times July 9, 1934). Cunningham had run the first three laps so fast that he had been unable to maintain his speed to the line. Bonthron had been wise enough not to match this speed in the third lap, but he had still run fast enough to keep his rival close enough for a final attack. It could be argued that Bonthron was lucky that Cunningham faded, but his decision in the third lap was a reasonable one in the circumstances. Bonthron had won what was undoubtedly one of the greatest American races of all-time, and he had defeated one of the sport’s greatest competitors. Bonthron was more interested in winning as opposed to breaking records, but he said to Coach Geis after this race, “I told you, Matt, I’d break the record for you today.” (New York Times, July 9, 1934)

European Disappointment

|

|

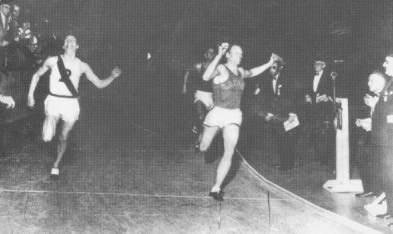

Lovelock outsmarts a desperate Bonthron at the White City. |

By this time Bonthron had been competing regularly for five months. It would have been a perfect time for him to end his season. However, Europe was on the cards. Sadly, he was unable to live up to the reputation that had preceded him across the Atlantic. European crowds saw a hint of his famous kick, but there was something lacking. He had recently announced that he would retire at the end of the season, so clearly his mind was focused on his future. Further, mental fatigue was affecting him. The media found his running lackluster.

Bonthron’s most important race was his first one: the Mile in the return match between Princeton-Cornell and Oxford-Cambridge. He was facing Jack Lovelock again, and it was billed as a race between the world’s two greatest milers. The race was very tactical with neither runner willing to up the pace and both waiting very late to make an effort. Bonthron should not have been surprised by Lovelock’s effort off the last bend, and although he finally reacted “still long-striding but rather laboured” (Times, July 22, 1934), he was a yard back at the tape. The winning time was a slow 4:15.4. After the race Lovelock commented on Bonthron: “There was nothing wrong with him but his judgment.” (Milers, p. 93) Bonthron admitted, “I was just outsmarted.” But he was also a tired man, and Coach Geis said he had trouble breathing in the heavy air. The Times called him “strangely lethargic” (August 7, 1934) which would have surprised anyone who had seen him run earlier in the year in the States. Bonthron also raced the 880 and did not impress. He let a much inferior runner, Stothard, get too far ahead and was unable to catch him. But at least the White City crowd got some intimation of the famous Bonthron finish when he tried desperately to catch the Englishman. Stothard’s winning time was a lowly 1:58.5.

Over on the continent, Bonthron won several races. He defeated Sweden’s Ny over 1,000 (2:28.8), won a couple of 1,500s (3:55.4, 3:54.4) and ran a fast 3:00.8 for Three-quarters of a Mile. This time was an unofficial world record. Then he met Lovelock for a second time in Amsterdam. Again he let Lovelock open up a gap and again, despite a late sprint he ended up in second, 3:53.3 to 3:54.1. The competitive intensity that Bonthron had shown earlier in the year had been weakened by fatigue. Only in his last race, a 1,500 in Paris, did he finally outsprint Lovelock. He had announced this as his last race on a cinder track, and although he won, it was a hollow victory. Lovelock reportedly did not take the race that seriously, wanting to test his ability to come back after Bonthron had sprinted past him. So Bonthron’s only European tour was a disappointment after his wonderful indoor and outdoor seasons in the States.

A Full-Time Job

Bonthron now faced a major change in his life. He was no longer a student and as a married man needed to make a living. In the fall he began working in New York City as an accountant, as well as attending night school. Although he originally said he would retire after graduating, he tried to keep in shape for the 1935 indoor season, training in the dark on the Millrose board track on the Wanamaker department-store roof. “Business and running just do not mix,” he told the press. “I can’t work until a few hours before a meet and be at my best. And I can’t train properly in the brief time I have to myself after work.” (New York Times, February 21, 1935) There were reports that without the supervision of his Princeton coach he was not training well. And when the track became covered with snow and ice in the winter, he refused to train indoors.

Not surprisingly his indoor form disappointed. In the 1935 Wanamaker Mile he managed to stay with Cunningham’s pace, even when a 61.9 third quarter took them through in 3:09.2. But then Venzke passed him and the famous Bonthron closing drive never materialized. While Cunningham and Venzke battled at the front, Bonthron was well back in third with 4:16.8 to Cunningham’s 4:11.0. It was the same story in the Baxter Mile, a third behind Cunningham and Venzke. “This has been a pretty sad indoor season for me,” he said. (New York Times, February 21, 1935) He decided to make the AAU his final indoor meet, and he put in his best performance of the season, managing to earn second place behind Cunningham. He made a huge charge in the last lap and a half, but could make no impression on Cunningham, who broke his own indoor world record of 3:52.2 (which he co-held with Bonthron) with 3:50.5. Bonthron finished 30 yards behind.

Yet Another Princeton Mile

|

|

Princeton Mile 1935. Bonthron tries to stay Cunningham and Lovelock. |

He now set his eyes on the outdoor Invitation Mile at Princeton in June. It was to be his swansong, having written off any plans to run in the 1936 Olympics. Like most college athletes of the time, his attitude was that competitive running was to be done only during university years. But because of his great successes in 1933 and 1934, he went against the grain, if only for a short period.

The Princeton 1935 Mile attracted Lovelock and Cunningham again. Bonthron trained through the spring and began to show form with a 3:04 ¾ time-trial. Cunningham was also showing good form, having run a 1:52.2 800, but his strength was suspect after a bad bout of flu. A week before the race both Bonthron and Lovelock ran 660 time-trials. Lovelock clocked 1:21.2, his fastest ever, only to learn that Bonthron had run 1:20, although the distance was later found to be 21 yards short. According to The Milers, “It fooled Bonthron even more than it caused fear in Lovelock.” (98)

|

|

Bothron's best comeback race in 1935. He passes Cunningham to take second in the Princeton Mile. |

There was widespread interest in the Invitation Mile, and the 40,000 Princeton crowd was there to cheer for their hero Bonthron. The Princeton graduate faced two great milers: Cunningham who was one of the toughest competitors ever, and Lovelock who was one of the canniest. Additionally, his 660 time-trial had given him a false idea of his fitness. The tension of the competition caused some bizarre events on the first lap when Cunningham rushed to the lead with Glen Dawson and then slowed the pace to 64.9 at 440. Cunningham then put in a 60.8 lap. Only Lovelock and Bonthron stayed with him. The pace slowed a little, Cunningham still leading with a 63.2 lap for 3:08.9 at the bell.

Bonthron began to drop back on the final lap. He watched Lovelock surge easily into the lead in the final 100 and then set off in a desperate but successful sprint to catch Cunningham. Result: 1. Lovelock 4:11.2; 2.Bonthron 4:12.6; 3. Cunningham 4:13.0. He had done well on his limited training to beat Cunningham but admitted he knew all along that he couldn’t beat Lovelock. After this race he announced his competitive career was over.

The Lure of the Olympics

But it wasn’t. The opportunity to run in the Olympics was too tempting for him, and he was soon training for the 1936 outdoor season. After joining the New York Athletic Club he did some of his training (three times a week) with a group in NewYork’s Central Park. All his focus was on making the Olympics. To help him achieve this goal he was again working with his Princeton coach Matty Geis. Part of the coach’s advice was to forego the indoor season; some commentators argued that this was not a good plan. Following a winter’s conditioning, Bonthron had only one race before his first big race, the 1936 Princeton Invitational Mile. This was impressive: a relaxed 3:07.9 fourth place behind winner Hornbostel’s 3:05.5 in a Three-quarter Mile.

There was great excitement over the Princeton Mile. Venzke and Cunningham, both coming off a successful indoor season, were in the field. Commentators believed that Bonthron’s lack of competition would tell. They were right. Predictably Cunningham set a fairly fast pace, and he and Venzke dropped Bonthron after three laps. According to The New York Times, “He had nothing left.” While Cunningham won in 4:13.4, Bonthron could only manage 4:19.8 for fourth place. Still his basic fitness was good and the next week he won the Metropolitan AAU 1,500 in atrocious conditions (4:00.1) and was second in the 800.

There was still a long way to go, but hopes were raised a week later when he beat Venzke in a preliminary Olympic trial with 3:55.2. Venzke, who was so far unbeaten outdoors, led until the last 60, when Bonthron sprinted to the lead. At this point in the season, it looked like Bonthron might well get into the 1,500 trio for Berlin with Cunningham and Venzke. But then Archie San Romani appeared on the scene and placed second to Cunningham in the AAU 1,500. Bonthron placed only fourth this time. His plan was to stick close to Cunningham, and he stayed with this plan when Venzke opened up a 20-meter lead on Cunningham. Bonthron was able to move up to Venzke with Cunningham on the backstretch. But the effort was too much for him, and he had to watch Cunningham burst ahead for victory from San Romani and Venzke. Significantly, Bonthron was not able to initiate his sprint in a relatively slow race (3:54.2).

For the Olympic trial there were five serious candidates: Cunningham, Fenske, Venzke, San Romani and Bonthron. All had run a sub-4:11 mile. The first 700 was a procession with the field bunched. Then Bonthron took the lead for half a lap before Venzke and Cunningham passed him. Coming into the bell lap San Romani and Fenske moved into the lead, leaving Bonthron fifth. On the back straight Cunningham moved up to second, waiting to make his final effort. Round the final bend, Bonthron could make no impression on the leaders, although he did manage to pass Fenske. Fourth place meant failure. The 1,500 world-record-holder would not be going to Berlin. Although he had claimed a growing fondness for training after work, the regime he had been living under for almost two years was not sufficient to keep him as sharp as he had been in his university days. Had he managed somehow to get to Berlin, it’s doubtful whether he would have been a factor in the final.

Retirement

After the Olympics trials, Bill Bonthron did retire for good. His focus became family and work. He fathered six children and settled in Princeton. This meant that he had to commute for two hours each working day to his New York office. He worked hard as a Tax Manager for Price Waterhouse, often going in to the office on Saturdays. Late in life he developed emphysema and died when only 70.

Note: I am most grateful to Lynn McConnell for the well-researched material on Bill Bonthron in his book The Conquerors of Time.

1 Comment