1948 Olympic Games

|

London, England

July 29-August 14

With Great Britain still recovering from WW2, there was much opposition against holding the 1948 Olympic Games in London. Britons were still subject to severe rationing and economic hardship. Thus expensive preparation for the sake of mainly foreign athletes was seen as a lesser priority. However, teams from abroad brought their own food and gave the surplus to hospitals. And frugal utilization of existing facilities lowered the costs.

|

Psychologically, Britons needed a morale booster. And the Olympics definitely fitted the bill. Emil Zatopek had experienced the ravages of war in Czechoslovakia, and he clearly saw how badly needed the games were: "After all those dark days of the war, the bombing, the killing, the starvation, the revival of the Olympics was as if the sun had come out....I went into the Olympic Village and suddenly there were no more frontiers, no more barriers. Just the people meeting together. It was wonderfully warm. Men and women who had just lost five years of life, were back again." Despite the inability of the war-torn host nation to provide the best of facilities and accommodation, these Games produced large crowds and some fine competition. The White City stadium, where the athletics competition was held, saw crowds from 60,000 to 70,000 despite the often rainy weather.

Note: Japan and Germany were not invited to these games.

800

|

| Whitfield controls from the front. Wint, Chef D'Hotel and Barten follow. |

An impressive field lined up for the final of this event. Frenchman Marcel Hansenne had the best time of the year: 1:48.3, while Sweden’s Bengtsson had a recent 1:49.3 to his clocking. The Americans had three finalists, of whom Mal Whitfield was the most favored. The very talented Jamaican Wint had run 1:50 in 1947 and was expected to be in the race at the end. Britain was represented by Parlett, who was expected to uphold the fine British record in this event.

After a predictably scrambling start (no lane staggering), the field reached the bell in 54.2, with the two French runners leading, Chef D’Hotel and Hansenne. At this point Whitfield took the lead. He then managed to control the race from the front, although he was challenged all the way down the back straight by Bengtson. Around the turn Wint moved into contention and looked perfectly placed to catch Whitfield. But the American’s strength enabled him to just hold off the Jamaican. Hansenne finished well to claim the bronze.

|

| Whitfield holds off Wint. Hansenne (51) is third. |

Overall the Americans impressed with all three finishing in the top six. The big disappointment was the host country’s Parlett. Likely spurred by the home crowd, he ran too fast in his semi-final and then used up too much energy at the start of the final to get into a good position (he was on the outside at the start line). The Brit finished well back in eighth.

1. Mal Whitfield USA 1:49.2; 2. Arthur Wint JAM 1:49.5; 3. Marcel Hansenne FRA 1:49.8; 4. Herb Barten USA 1:50.1; 5. Ingvar Bengtsson SWE 1:50.6; 6. Bob Chambers USA 1:52.1.

1,500

The favorite, Lennart Strand, came into the Olympics as the WR holder at 3:43.0. Another Swede, Henry Eriksson, was expected to make the pace for his countryman, but he had been beaten every time in over a dozen races by Strand’s devastating kick. The Swedish third string, Gosta Bergkvist, had actually won the Swedish trials. Indeed, it was quite likely that the Olympic final would be a clean sweep for Sweden. Their main opposition was expected from Marcel Hansenne of France, who had just won the 800 bronze and who had run well over 1,500 in 1946 and 1947. Also, in the picture was Vaclav Cevona of Czechoslovakia, who had a 3:49.4 clocking in June. A wild card was Dutchman Wim Slijkhuis; he had won a silver medal in the 1946 European 5,000 and was very competitive at 1,500 as well.

|

| Eriksson moves into the lead from Hansenne, Strand and Bergvist. |

With rain still falling after a heavy downfall, the race started fast with 800-bronze-medalist Hansenne (ranked 4th in the 1,500 in 1947) roaring through 400 all alone in 58.3. But he slowed in the second lap to 64. The three Swedes caught him just after 800, which he passed in 2:02.6. Eriksson then took the lead and had a 3m gap on the field at 1,000. He continued to pile on the pace so that at 1,200 (3:05.0) only Strand was with him. Eriksson and Strand were locked together down the back straight and round the bend. Behind them the third Swede Bergkvist led Slijkhuis.

Strand looked the likely winner as he drew up beside Eriksson on entering the final straight. But this time it was Strand who faltered. With 50m to go Eriksson moved ahead as Strand tied up completely. The fast-finishing Slijkhuis, after passing Bergkvist, also tried to pass Strand on the inside just before the finish. But the Swede held his ground, and the two runners bumped. Slijkhuis was briefly knocked off the track. Strand was judged second—in the same time as Slijkhuis.

It was the first time that Eriksson had beaten Strand. There was talk that Strand was more highly strung and that the big occasion was his undoing. But this race was won rather than lost, and Eriksson should be credited with producing his best performance when it really counted. As for Slijkhuis, his amazing final 100m indicated that he should have been closer to the leaders in the last lap. With better tactics he might have grabbed the gold. Cevona ran well; his time on the sodden track was probably worth at least his 3:49.4 seasonal best. Bergkvist gave his best for third but faded at the end. Nankeville, who carried the hopes of the British crowd, ran as well as he could have hoped for sixth.

1. Henry Eriksson SWE 3:49.8; 2. Lennart Strand SWE 3:50.4; Willem Slijkhuis NED 3:50.4; 4. Vaclav Cevona CZE 3:51.2; 5. Gosta Bergkvist SWE 3:52.2; 6. Bill Nankeville GBR 3:52.6.

5,000

(Also posted as Great Races #6)

After his surprising win over WR holder Heino in the 10,000, Emil Zatopek lined up for the 5,000 as the crowd favorite. But there were two concerns about his chances: first, whether he had recovered from the earlier race, especially since he had put in a needless sprint at the end; and second whether his pointless race with Sweden’s Ahlden for first place in the heats would take the edge off him. Others pointed out that the five-and-ten double hadn’t been achieved since Kolehmainen did “the impossible” 36 years earlier. Zatopek himself, after losing to Ahlden in the heats, thought that the Swede might just get the better of him in the final.

For the final, it was raining and cool, and the track was soft and muddy. Zatopek, who had hung back in the early laps of the 10,000, went immediately into the lead. Soon the runners were all splattered with dirt as the rain continued. He passed 2,000 in a very fast 5:38, which was 14:05 speed—a finishing time hardly feasible on the waterlogged London cinder track. Behind Zatopek were Belgium’s Gaston Reiff, Holland’s Slijkhuis and Ahlden. Lap after lap, these three doggedly held on to the Czech. Not surprisingly Zatopek slowed to a 2:55 third K.

|

| Reiff And Ahldén follow Zatopek in the early stages. |

In the fourth K (2:52), Reiff and then Slijkhuis passed him. Soon Reiff opened up a gap on Slijkhuis. Reiff said later that he didn’t want the pace to slow too much because he was afraid of the finishing speed of Slijkhuis. Resigned to finishing third, Zatopek slipped back until he was 60 metres behind Reiff and 30 behind Slijkhuis. Then, with less than 600 to go, he decided to go after Slijkhuis and made up 10m just before the bell.

Although Slijkhuis made an effort at this point, Reiff also increased his pace to hold off the Dutchman. Coming round the last bend, Reiff looked to have the race won as Slijkhuis suddenly slowed and was passed by the charging Zatopek. Then the Czech suddenly realized that Reiff was also slowing and took off again with a full 20 meters to make up in little more than 100 meters. Hearing the crowd go wild, Reiff looked round to see the thrashing Zatopek bearing down on him. Both runners drew on their last reserves as the gap narrowed and narrowed. At the tape only 2/10 of a second separated them: Reiff had held on by a proverbial whisker, 14:17.6 to 14:17.8. Reiff later said that the home straight was the toughest of his whole career. Zatopek’s last lap was estimated by John Rodda to be close to 60 seconds. He was gracious in defeat and blamed himself for leaving too much to do in the last lap (“ I had been too stupid.”). But this race increased his prestige with the public: he had almost done the impossible in the last lap.

Reiff, 27, had made a dramatic improvement on his fifth place in the 1946 European 5,000, when he finished close to 40 seconds behind winner Wooderson in 14:45. He continued competing until 1953, setting world records at 2,000, 3,000 and 2 Miles. He won a bronze in the 1950 European 5,000, but this Olympic 5,000 race was his greatest.

1. Gaston Reiff BEL 14:17.6; 2. Emil Zatopek CZE 14:17.8; 3. Willy Slijkhuis NED 14:26.8; 4. Erik Ahlden SWE 14:28.6; 5. Bertil Albertsson SWE 14:39.0; 6. Curtis Stone USA 14:39.4.

10,000

Close to 70,000 spectators endured the sweltering heat at London’s White City to watch the 10,000 final—even though there was no home favorite for this event. Viljo Heino, the Finnish favorite and world-record holder (29:35.4), was expected to take gold. However, there was a promising 5,000 runner from Czechoslovakia, Emil Zatopek, who had placed 5th in the European 5,000 in 1946 and had come within 3 seconds of Heino’s WR three weeks earlier.

Heino took the lead from the start, although he was not in top form after an injury. He led at a fast pace through the first K in 2:55.6 (29:16 pace). Heino maintained the pace to 2K (5:52) but then slowed a little to 8:31.0 at 3,000. As storm clouds built up in the stifling heat, the Czech runner in a faded orange vest, who had stayed well back in the early laps, moved through the field from 17th and into the lead on the 10th lap. Emil Zatopek was about to put his stamp on distance-running history. His style of running was very unorthodox, with his rolling head and swaying shoulders. His continual grimacing suggested he was always about to crack. But he didn’t.

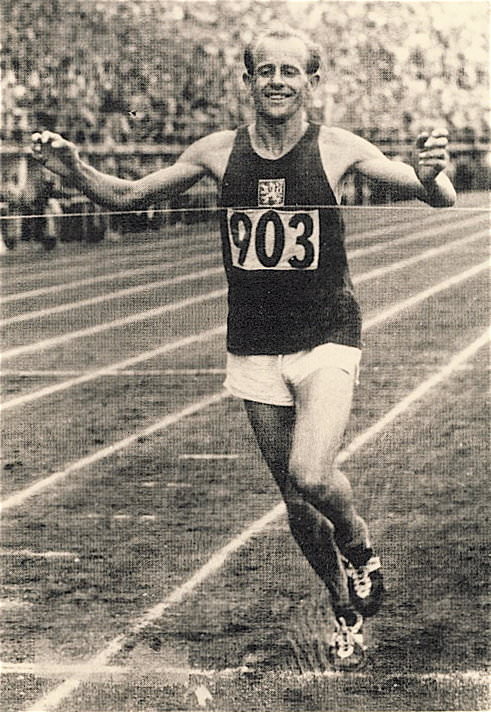

|

| Zatopek wins by over half a lap. |

Heino, whose elegant running style contrasted the Czech’s, was back in the lead at the halfway point (14:57). The fast early pace was beginning to tell. When Zatopek went back into the lead, Heino held on to him for six laps. The pace was slowing to 3:05 and 3:03, but Heino was in trouble and he dropped out just before the 7K mark with stomach trouble. For the last eight laps Zatopek was on his own. No doubt initiated by his fellow countrymen, a chant of Za-to-pek, Za-to-pek was soon swirling around the stadium. The new Czech hero ran he last 3K in 8:55 to post a 47-second lead at the end. His time of 29:59.6 was 12 seconds inside the Olympic record.

Behind Zatopek, Alain Mimoun-o-Kacha was the only one in the top six to run a PB. The Algerian-born Frenchman had a comfortable 6-second margin over Sweden’s Albertsson in becoming the first North African (of many to come!) to win a distance track medal. It would be easy to think that Mimoun had an advantage with the heat, but he went on to show that this fine run was no lucky break. He became one of the great distance runners of the 1950s.

1. Emil Zatopek CZE 29:59.6; 2. Alain Mimoun FRA 30:47.4; 3. Bertil Albertsson SWE 30:53.6; 4. Martin Stokken NOR 30:58.6; 5. Severt Dennolf SWE 31:05.0; 6. Abadallah Ben Said FRA 31:07.8.

Marathon

The Marathon produced one of the closest finishes in Olympic history. There were 41 runners on the start line. The favorite was Korean Yun Bok Suh, who had run a world best 2:25:39 in the 1947 Boston Marathon. The best European runner was Finland’s Mikko Heitanen, who had run second to Suh in that marathon some 4 minutes behind. Also fancied was Britain’s Jack Holden. The 39-year-old was at the end of a distinguished career as a cross-country and road runner.

After Argentine Eusebio Guinez had led early in the race, Belgium’s Etienne Gailly took over and led through 10K in 34:34. This was an ambitious start for someone starting his first marathon. He led China’s Lou Weng-au by 12 seconds and Rene Josset of France and Guinez of Argentina by 31 seconds. Not a lot changed in the next 10K. Gailly still led at 20K in 1:09:29, with Lou 24 seconds behind. Guinez and Josset were still third and fourth. They were followed by Ostling of Sweden and Cabrera of Argentina (1:10:51). Holden and Luyt were close behind. Heitanen dropped out soon after 20K.

At 25K (1:27:27) Gailly had moved farther ahead, increasing his lead on Guinez to 43 seconds. Ostling and Cabrera had past Lou and Josset into third and fourth. The runners now had to negotiate a steep hill. This climb saw Korea’s Choi move up quickly from 8th to 3rd as he gained over a minute on the leader. At this time the British favorite had to abandon the race with blisters.

At 30K Gailly (1:47:01) still led Guinez by 32 seconds. A further 20 seconds back were Choi and Cabrera. Then came Ostling, Luyt, and Richards of Britain. Choi roared ahead in the next 5K to a 28-second lead, while Cabrera was just ahead of a slowing Gailly in second. They were followed by Guinez, Richards and Luyt.

A dramatic change occurred in the 38th K: the leader Choi began to limp and then he dropped out. Then near 40K there were some more changes. Gailly surged back into the lead and Guinez began to slow. At the same time Tom Richards of Britain moved up to third and Coleman of South Africa, the1938 Empire Games winner, moved into fourth.

|

| Running in the wrong lane, Cabrera passes Gailly soon after entering the stadium. |

While these changes were dramatic, they were nothing like the changes that happened inside the stadium during the final moments of the race. Gailly, now looking unsteady, entered the stadium first, just ahead of Cabrera. The Argentine looked fresh by comparison and quickly passed the Belgian and finished 42 seconds ahead of him in 2:34:51.6. But Tom Richards also came into the picture as he entered the stadium not long after Cabrera and soon passed Gailly as well. He was only 16 seconds behind Cabrera at the finish. Gailly tottered across the line in third, to be followed in roughly half-minute intervals by Coleman and Guinez.

So Cabrera earned Argentina’s second Olympic Marathon gold in three Olympics, Zabala having won in 1932. Relatively unknown internationally, the 29-year-old had competed at shorter distances for most of the 1940s. This was his first international competition. Gailly’s courageous run earned him universal admiration. He pushed himself so hard that he was hospitalized after the race and was unable to attend the medals ceremony. Tom Richards’ silver medal was unexpected. He had won two wartime Poly Marathons, but had finished second to Holden in both the 1947 and 1948 races. He thus entered the race a the second-string to Jack Holden. However, the 38-year-old Welshman ran a PB in this race for his greatest competitive performance.

1. Delfo Cabrera ARG 2:34:51.6; 2. Thomas Richards GBR 2:35:07.6; 3. Etienne Gailly BEL 2:35:33.6; 4. Johannes Coleman SAF 2:36:06.0; 5, Eusebio Guinez ARG 2: 36:36.6; 6. Syd Luyt SAF 2:38:11.7.

4 Comments