Major Games

1948 Olympic GamesLondon, EnglandJuly 29-August 14With Great Britain still recovering from WW2, there was much opposition against holding the 1948 Olympic Games in London. Britons were still subject to severe rationing and economic hardship. Thus expensive preparation for the sake of mainly foreign athletes was seen as a lesser priority. However, teams from abroad brought their own food and gave the surplus to hospitals. And frugal utilization of existing facilities lowered the costs. Psychologically, Britons needed a morale booster. And the Olympics definitely fitted the bill. Emil Zatopek had experienced the ravages of war in Czechoslovakia, and he clearly saw how badly needed the games were: "After all those dark days of the war, the bombing, the killing, the starvation, the revival of the Olympics was as if the sun had come out....I went into the Olympic Village and suddenly there were no more frontiers, no more barriers. Just the people meeting together. It was wonderfully warm. Men and women who had just lost five years of life, were back again." Despite the inability of the war-torn host nation to provide the best of facilities and accommodation, these Games produced large crowds and some fine competition. The White City stadium, where the athletics competition was held, saw crowds from 60,000 to 70,000 despite the often rainy weather.

1950 European Championships

1950 European Championships Brussels, August 23-27 800Boysen of Norway, who had run a fast 1:48.7, was the clear favorite. Hansenne and Bengtsson were also highly favoured. The British were not expected to be in the medals, even by their own supporters. Bannister, who had just completed his Oxford finals, admitted, “I was ill-prepared for such an important race.” (Bannister, First Four Minutes, p.101) Boysen shot away at the start and created a huge 15m lead. His lead at the bell (53.8 but 51.8 in T&FN) was 10m from Swedes Bengtsson and Linden. Hansenne and Bannister were a few yards behind him, and Parlett and Clare were even further back. Hansenne moved hard round the curve with Bengtsson on his heels. At 260m to go Bannister caught them and moved into second. The three of them were now catching the flagging Boysen. Coming into the straight Bannister and Hansenne had passed Boysen together and prepared for a duel over the last 80 meters. But behind them Parlett was smoothly making up ground.

1952 Olympic Games

1952 OLYMPIC GAMESHELSINKI, FINLANDJULY 19-AUGUST 3 Performances were much better than in the previous Olympics. Recovery from the stresses and deprivations of the Second World War meant that runners were able to train harder and eat properly. Zatopek, with his triple crown, outshone all other runners. 800 Mal Whitfield, 31, the 1948 800 Olympic champ, showed his strength and maturity in this race. He had been flying bombing missions in the Korean War, but was given time off for the Olympics. After a false start by Nielsen, the race started slowly with the elegant Wint leading the first lap in 54.0. Whitfield, who had started last to stay out of the wind, moved up a few places on the back straight and then eased into third at the bell. On the back straight he surged past Heinz Ulzheimer of Germany and his longtime rival Arthur Wint to gain the lead just before the bend. These two held on to him round the last bend, but he had control of the race. When Wint got within a yard, Whitfield was able to accelerate just enough to hold him off. It was a classy and economic performance by the American, who had the 400 and the 4x400 relay ahead of him. “I had plenty left in the stretch,” he told Track & Field News.

1954 Empire Games

1954 EMPIRE GAMESVANCOUVER, CANADA, July 30-August 7 These games were the most famous of all the Empire (and later, Commonwealth) Games. The intriguing four-minute mile barrier had been finally broken in 1954, first by Roger Bannister and then by John Landy. Now these two milers were to meet head-on in the games. The excitement surrounding this clash built to a high pitch. However, excessive enthusiasm had some negative effects not only on the race itself but also on the Marathon, which was in progress while the Mile race took place.

1954 European Championships

1954 European ChampionshipsBern, Switzerland, August 25-29 Despite the modest location, Berne Neufeld Stadium, this meet produced some stellar performances, including three WRs and 16 meet records. As Track and Field News (7.8) said, “These Games were probably second only to the Helsinki Olympics.” Bannister followed up his Vancouver victory with another major title here. The biggest news was the emergence of a new distance star: Vladimir Kuts. At the same time it was evident that Zatopek was no longer a threat over 5,000. The best race was undoubtedly the 800.

See all Major Games articles

Profiles

Profile: Alan Simpsonb. 1940 Alan Simpson was one of the most successful 1,500 runners during the 1960s. In his prime this fierce competitor rarely lost a race. He had an amazingly successful record in the two-a-side international competitions that were very popular at that time, winning 14 of his 17 races for his country. He set British records for 1,500, the Mile and 2,000, won the Mile British title three consecutive years (1963-65), and represented England in the International Cross-Country Championships. His best performance in major competitions was fourth in the 1964 Olympic 1,500; as well, though neither performance pleased him, he won a silver medal at the 1966 Commonwealth Games and placed fourth in the 1966 European 1,500.

Albie Thomas

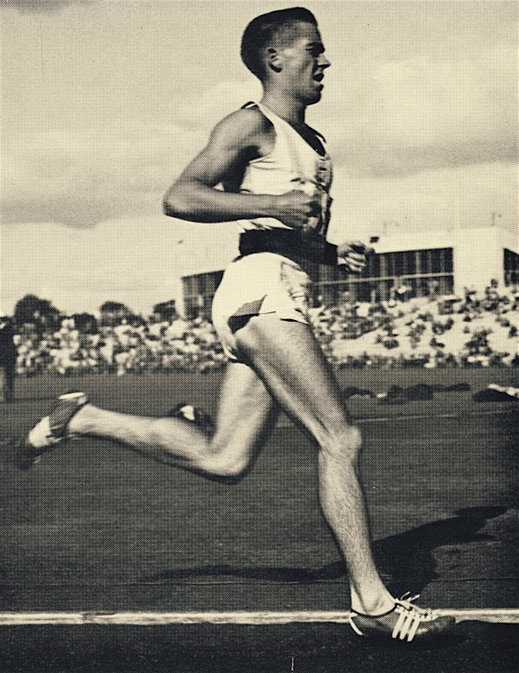

Albie Thomas: Profile 1935-2013When 21-year-old Albie Thomas of Australia burst on to the international scene with a fifth place in the 1956 Olympic 5,000, coach Percy Cerutty considered him the “best runner, technically speaking, in the world today.” (Middle-Distance Running, pp.49-50) Eighteen months later, Thomas fulfilled the great promise Cerutty had seen in him with an amazing 59 days of racing on the European circuit, during which he won nine of 16 races. In these races he not only broke two world records (Two Miles and Three Miles) but also won two Commonwealth Games medals, broke the Australian 3,000 record, ran a 4-minute mile, paced Herb Elliott to both his Mile and 1,500 world records and won the Three Miles in the British Games.

Anders Garderud Profile

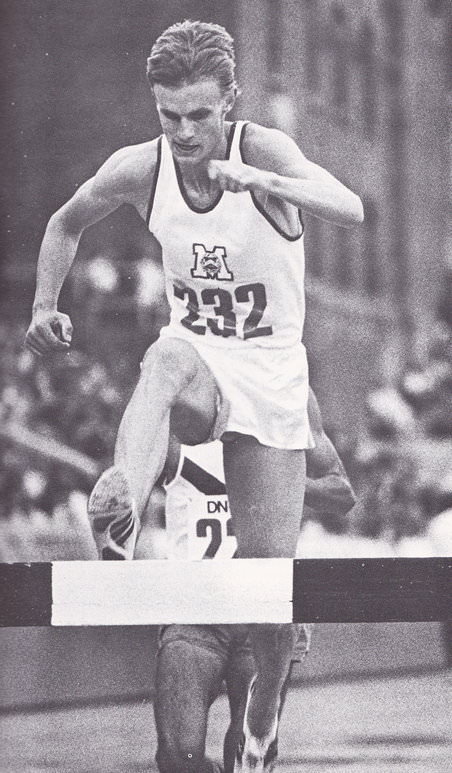

Anders Gärderud Profileb. Aug. 28, 19466’1” (1.86 m) 154 lbs (70 kg) The story of Anders Gärderud is a story of promise fulfilled. It’s also a story of setbacks and of the need for a radical reassessment of a running career. Gärderud has been Sweden’s greatest runner since Andersson and Hägg. Thirty years after these two great runners had rewritten the record book for 1,500 and the Mile, he broke the world Steeplechase record four times over a four-year period, reducing it an amazing 12.6 seconds. And he capped off his career in the best way possible with an Olympic gold medal in a world-record time.

Arne Andersson

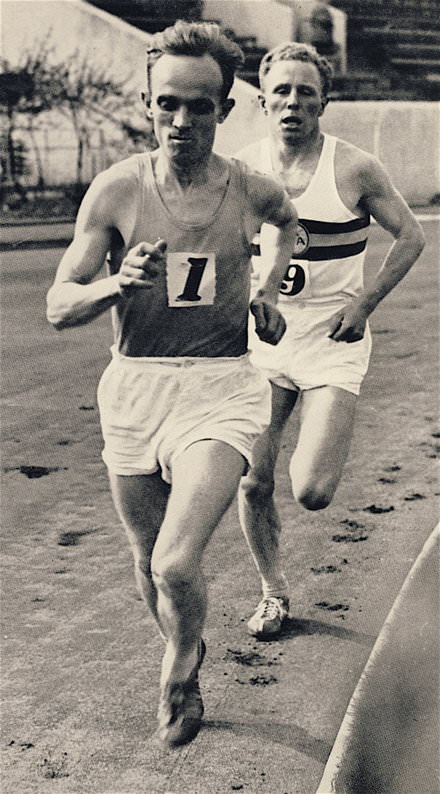

PROFILE: ARNE ANDERSSON1917-2009b. Trollhätten, Sweden. 70kg/154lbs 5’10”/1.78 It was a great honour for the 21-year-old Arne Andersson to represent Sweden in the 1939 Finnmark competition against Finland. For his international debut, he had been chosen as the second string to Åke Jansson in the 1,500 after improving his 1938 PB by five seconds with 3:53.8. His role in the four-man race was to help Jansson win by pacing him until the final stages. Jansson, with a 3:52.4 PB, was expected to need help as his two Finnish adversaries, Hartikka and Sarkama, were also 3:52 runners.

Basil Heatley

PROFILE: BASIL HEATLEY 1933-2019 From 1948 through to the 1960s, English runner Basil Heatley improved steadily, winning countless titles on the road, track and country. Among his most notable achievements were a World-Record 10 Miles, an International Cross-Country title and three National Cross-Country titles. As he approached retirement, the one achievement he lacked was participation in a major games. He had come close, narrowly missing selection for the 1958 Empire Games and for the 1960 Olympics, and then being injured during the build-up to the 1962 Empire and European games.

See all Profile articles

Great Races

Arne Andersson v Gunder Hägg (1944)1,500 Gothenburg, Sweden, July 7, 1944Great Races #4 In his first race of 1944, Gunder Hagg had been humiliated by Arne Andersson in a 1,500 race. Andersson had stayed with Hagg throughout and then roared by in the last 120 to open up a nine-meter lead. Hagg’s defeat had been so decisive that rumours spread that the great man had thrown the race.Clearly Gunder Hagg had to recapture his reputation as the world’s greatest runner. His plan was simple. In view of the devastating finishing kick that Andersson had demonstrated, a kick that seemed to be more potent than ever, Hagg would literally have to run his opponent off his feet with a blistering pace. To help with this plan, Hagg enlisted the help of 23-year-old Lennart Strand, who was to win a gold medal in the 1946 European Championships and a silver in the 1948 OG—both in the 1,500.

Arne Andersson v Gunder Hagg (Mile, 1944)

Gunder Hagg v. Arne AnderssonOne MileMalmo, Sweden, July 18, 1944A capacity crowd paid to see yet another great race between Arne Andersson and Gunder Hagg. The two Swedish runners had been rivals since 1942 and had had many exciting duels, often setting WRs in the process. Hagg had beaten Andersson every time in 1942, but this year, Andersson appeared to be Hagg’s equal. Not only had he beaten Hagg’s WRs for 1,500 and the Mile in 1943, but he had also beaten Hagg in their first 1944 encounter over 1,500. Then Hagg had won the second race. Clearly this third encounter of the season was going to be a classic.

Bannister v Landy (1954)

Bannister v Landy1954 Empire Games Mile, Vancouver, CanadaGreat Races #9 The build-up to this race was incredible. Athletics, as one of the truly international sports, had followers all over the world. The first four-minute mile had captured the imagination of millions. And now the first two runners to have broken that barrier earlier in the summer, Roger Bannister and John Landy, were to meet in the Vancouver Empire Games. The race received huge coverage in the world press. It was given an array of names, The Miracle Mile, The Mile of the Century. As well, the television cameras were ready to supply the new medium live to an estimated 10 million North American viewers. Radio provided live coverage to the rest of the world. Bannister and Landy had become celebrities, hunted down by reporters and cameramen as soon as they arrived in Vancouver. The two runners dealt with the situation in different ways: Bannister avoided attention as much as he could and trained in private; Landy was happy to talk to anyone and trained in public.

Bannister's 3:59.4 (1954)

Bannister's 3:59.4 First Four-Minute Mile, Oxford, UK, May 1954Great Races #8 The black-and white photo of Roger Bannister crossing the finish line in Oxford on May 6, 1954, is one of the most famous in the history of running. Head back, eyes closed and mouth agape, with transfixed spectators and an overwhelmed official in the background, Bannister is caught a fraction of a second before he breasts the tape just less than four minutes after the starter’s gun had fired. This was the moment that man first broke four minutes for the Mile. It was a symmetrical barrier: four laps of a quarter-mile track to be run in less than one minute per lap. Several athletes had come close over the previous dozen years. Yet there was something about the symmetry of the four-minute mile that made is seem impossible. This impossibility had surely affected Hagg and Andersson in the 1940s. And the same psychological effect was felt by the leading milers in the 50s when John Landy, Wes Santee and Roger Bannister were all “racing” towards the first sub-4. The story of these three great runners’ attempts to be the first is finely recounted by Neal Bascomb in his book The Perfect Mile.

Bolotnikov v Tulloh v Zimny (5,000, 1962)

Bolotnikov v Tulloh v Zimny5,000 European Championships 1962Great Races #15 Following his convincing 10,000 win, Russian Pyotr Bolotnikov (See Profile) looked a good bet for this race too. But his heat for this final was held only 24 hours after his 10,000 final. Further, he was forced to run a fast 13:53.4 to qualify (10th fastest time in the 1962 world rankings), so the recovery powers of this 32-year-old Russian were sure to be tested. The two other heats were won in the slow times of 14:14 and 14:15. Janke, who had run so well in the 10,000 was still tired and could manage only 8th in his heat. Prominent among the qualifiers were Zimny and Boguszewicz of Poland and Frenchmen Bogey and Bernard. Englishman Tulloh thought he had a chance. He had run a four-minute Mile and an 8:33.4 Two Miles in January, which meant he had the best basic speed in the field, but he had recently been beaten by Zimny.

See all Great Races articles

1940s

1948 Olympic GamesLondon, EnglandJuly 29-August 14With Great Britain still recovering from WW2, there was much opposition against holding the 1948 Olympic Games in London. Britons were still subject to severe rationing and economic hardship. Thus expensive preparation for the sake of mainly foreign athletes was seen as a lesser priority. However, teams from abroad brought their own food and gave the surplus to hospitals. And frugal utilization of existing facilities lowered the costs. Psychologically, Britons needed a morale booster. And the Olympics definitely fitted the bill. Emil Zatopek had experienced the ravages of war in Czechoslovakia, and he clearly saw how badly needed the games were: "After all those dark days of the war, the bombing, the killing, the starvation, the revival of the Olympics was as if the sun had come out....I went into the Olympic Village and suddenly there were no more frontiers, no more barriers. Just the people meeting together. It was wonderfully warm. Men and women who had just lost five years of life, were back again." Despite the inability of the war-torn host nation to provide the best of facilities and accommodation, these Games produced large crowds and some fine competition. The White City stadium, where the athletics competition was held, saw crowds from 60,000 to 70,000 despite the often rainy weather.

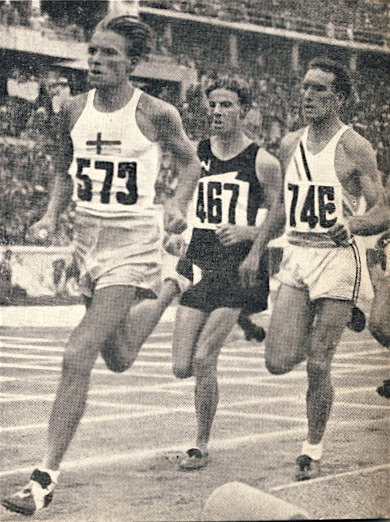

Arne Andersson

PROFILE: ARNE ANDERSSON1917-2009b. Trollhätten, Sweden. 70kg/154lbs 5’10”/1.78 It was a great honour for the 21-year-old Arne Andersson to represent Sweden in the 1939 Finnmark competition against Finland. For his international debut, he had been chosen as the second string to Åke Jansson in the 1,500 after improving his 1938 PB by five seconds with 3:53.8. His role in the four-man race was to help Jansson win by pacing him until the final stages. Jansson, with a 3:52.4 PB, was expected to need help as his two Finnish adversaries, Hartikka and Sarkama, were also 3:52 runners.

Arne Andersson v Gunder Hagg (1,500, 1944)

Arne Andersson v Gunder Hägg (1944)1,500 Gothenburg, Sweden, July 7, 1944Great Races #4 In his first race of 1944, Gunder Hagg had been humiliated by Arne Andersson in a 1,500 race. Andersson had stayed with Hagg throughout and then roared by in the last 120 to open up a nine-meter lead. Hagg’s defeat had been so decisive that rumours spread that the great man had thrown the race.Clearly Gunder Hagg had to recapture his reputation as the world’s greatest runner. His plan was simple. In view of the devastating finishing kick that Andersson had demonstrated, a kick that seemed to be more potent than ever, Hagg would literally have to run his opponent off his feet with a blistering pace. To help with this plan, Hagg enlisted the help of 23-year-old Lennart Strand, who was to win a gold medal in the 1946 European Championships and a silver in the 1948 OG—both in the 1,500.

Arne Andersson v Gunder Hagg (Mile, 1944)

Gunder Hagg v. Arne AnderssonOne MileMalmo, Sweden, July 18, 1944A capacity crowd paid to see yet another great race between Arne Andersson and Gunder Hagg. The two Swedish runners had been rivals since 1942 and had had many exciting duels, often setting WRs in the process. Hagg had beaten Andersson every time in 1942, but this year, Andersson appeared to be Hagg’s equal. Not only had he beaten Hagg’s WRs for 1,500 and the Mile in 1943, but he had also beaten Hagg in their first 1944 encounter over 1,500. Then Hagg had won the second race. Clearly this third encounter of the season was going to be a classic.

Bill Bonthron Profile

With his talents, American miler Bill Bonthron could have conquered the world. He had strength, speed and a tenacious competitive drive. But while he performed brilliantly in his own country and even set a world record for 1,500 in 1934, he made little impact on the international scene and never competed in an Olympic Games. Following the traditional amateur conventions of his time, Bonthron planned his athletic career for just the four years of his university education. Once he graduated and married, his priority was his job as an accountant and he announced his retirement from running in 1934. Although he later broke with convention and continued to train seriously in his spare time, he never regained the form of his university years and failed to qualify for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He did make one European tour in his graduating year, but failed to live up to the reputation that had crossed the Atlantic before his arrival.

See all 1940s articles

1950s

1950 European Championships Brussels, August 23-27 800Boysen of Norway, who had run a fast 1:48.7, was the clear favorite. Hansenne and Bengtsson were also highly favoured. The British were not expected to be in the medals, even by their own supporters. Bannister, who had just completed his Oxford finals, admitted, “I was ill-prepared for such an important race.” (Bannister, First Four Minutes, p.101) Boysen shot away at the start and created a huge 15m lead. His lead at the bell (53.8 but 51.8 in T&FN) was 10m from Swedes Bengtsson and Linden. Hansenne and Bannister were a few yards behind him, and Parlett and Clare were even further back. Hansenne moved hard round the curve with Bengtsson on his heels. At 260m to go Bannister caught them and moved into second. The three of them were now catching the flagging Boysen. Coming into the straight Bannister and Hansenne had passed Boysen together and prepared for a duel over the last 80 meters. But behind them Parlett was smoothly making up ground.

1952 Olympic Games

1952 OLYMPIC GAMESHELSINKI, FINLANDJULY 19-AUGUST 3 Performances were much better than in the previous Olympics. Recovery from the stresses and deprivations of the Second World War meant that runners were able to train harder and eat properly. Zatopek, with his triple crown, outshone all other runners. 800 Mal Whitfield, 31, the 1948 800 Olympic champ, showed his strength and maturity in this race. He had been flying bombing missions in the Korean War, but was given time off for the Olympics. After a false start by Nielsen, the race started slowly with the elegant Wint leading the first lap in 54.0. Whitfield, who had started last to stay out of the wind, moved up a few places on the back straight and then eased into third at the bell. On the back straight he surged past Heinz Ulzheimer of Germany and his longtime rival Arthur Wint to gain the lead just before the bend. These two held on to him round the last bend, but he had control of the race. When Wint got within a yard, Whitfield was able to accelerate just enough to hold him off. It was a classy and economic performance by the American, who had the 400 and the 4x400 relay ahead of him. “I had plenty left in the stretch,” he told Track & Field News.

1954 Empire Games

1954 EMPIRE GAMESVANCOUVER, CANADA, July 30-August 7 These games were the most famous of all the Empire (and later, Commonwealth) Games. The intriguing four-minute mile barrier had been finally broken in 1954, first by Roger Bannister and then by John Landy. Now these two milers were to meet head-on in the games. The excitement surrounding this clash built to a high pitch. However, excessive enthusiasm had some negative effects not only on the race itself but also on the Marathon, which was in progress while the Mile race took place.

1954 European Championships

1954 European ChampionshipsBern, Switzerland, August 25-29 Despite the modest location, Berne Neufeld Stadium, this meet produced some stellar performances, including three WRs and 16 meet records. As Track and Field News (7.8) said, “These Games were probably second only to the Helsinki Olympics.” Bannister followed up his Vancouver victory with another major title here. The biggest news was the emergence of a new distance star: Vladimir Kuts. At the same time it was evident that Zatopek was no longer a threat over 5,000. The best race was undoubtedly the 800.

1956 Olympic Games

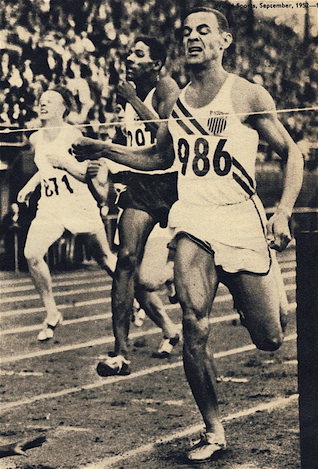

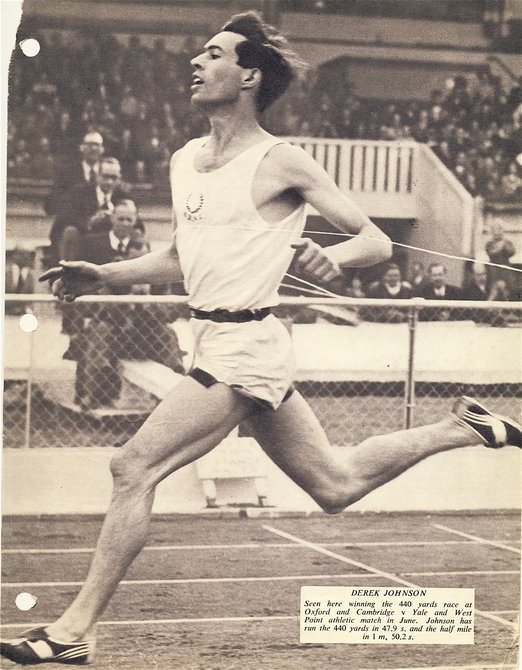

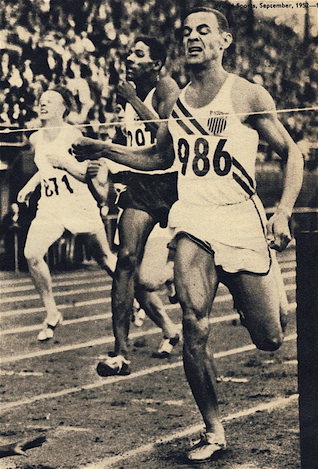

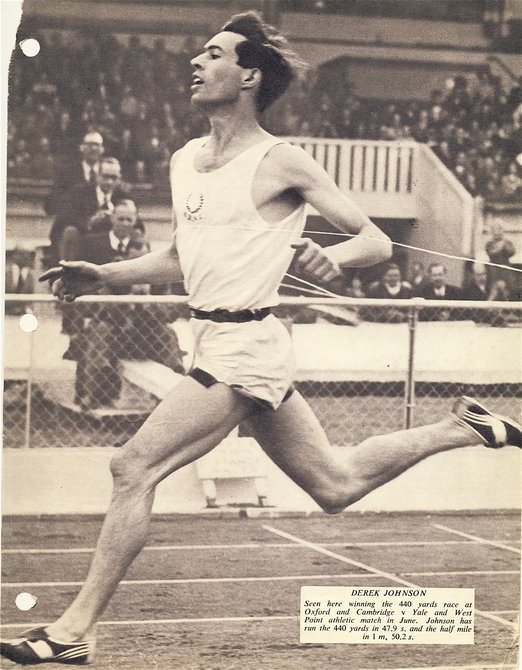

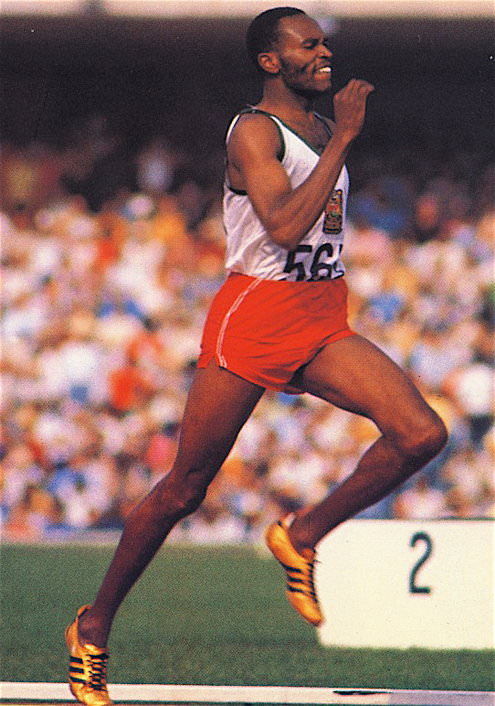

OLYMPIC GAMES 1956 Melbourne, Australia, November 22-December 8 800The finalists lined up in gusty conditions, while the last bend was still being compacted by two large rollers. Fortunately, the attention of the starters was alerted. After a delayed start, American Tom Courtney, who was the favorite for this event, went straight into the lead from compatriot Arnie Sowell and Britain’s Derek Johnson. On the back straight, Sowell took over and led Courtney and Johnson through 400 in 52.6. The two Americans stayed ahead in the next 200, while Boysen moved up to Johnson. On the crown of the last bend Courtney moved up beside Sowell, and the two Americans ran side by side into the final straight, with Johnson in hot pursuit. But then the Americans moved apart, allowing Johnson to sprint through between them. For “eight unbelievable strides,” as The Times correspondent put it (Nov. 27, 1956), Johnson was in the lead. But Courtney showed his amazing strength by responding and gaining a two-foot lead over Johnson at the tape. Boysen finished as fast as Johnson and was only 4/10 of a second behind Courtney for the bronze. A fading Sowell was fourth just 2/10 back.

See all 1950s articles

1960s

1960 Olympic GamesRome, August 25-September 11 800 Roger Moens (30), a very experienced runner with a great competitive record, was the co-favorite with Paul Schmidt, who had been fastest over 800 in 1959 (1:46.2). George Kerr (22) of Jamaica, a talented newcomer, was also fancied. The demanding heats eliminated two other top picks, Brian Hewson of Great Britain and Stefan Lewandowski of Poland (second fastest over 800 in 1959). The 800 race almost always provides a close finish. This time five of the six finalists were in a position to win as they entered the final stretch. As expected Christian Waegli led the field through the first 600 in 25.4, 51.9 and 1:19.1. Schmidt of Germany and Kerr of Jamaica followed, with Snell of New Zealand and Moens of Belgium close behind. At 600 Moens pushed into second place behind Waegli. Behind Moens, Snell was on the inside, boxed in by Schmidt and Kerr.

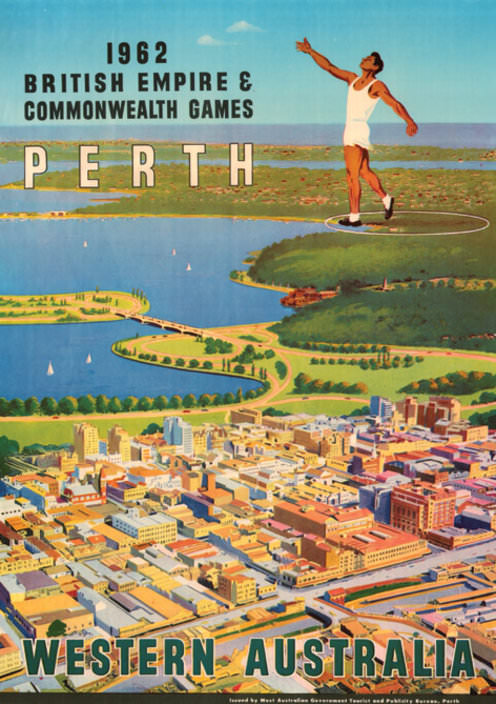

1962 Commonwealth Games

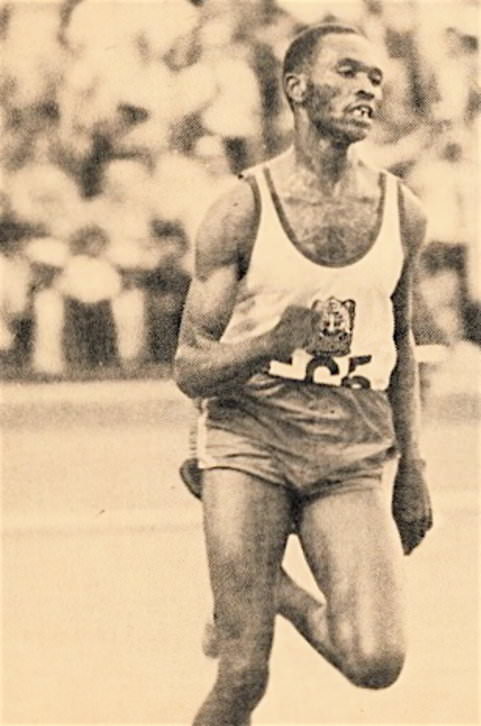

1962 BRITISH EMPIRE AND COMMONWEALTH GAMES Perth, Western AustraliaNovember 22-December 1 880This was a highlight race featuring two great rivals: Peter Snell of New Zealand and George Kerr of Jamaica. Although Snell had won six out of their seven encounters, Kerr was always able to push Snell to his limits. Kerr had finished third behind Snell in the Rome Olympics, after setting an Olympic record in the semis. And he was little more than half a second behind Snell in the final. Later in 1960, in New Zealand, Kerr defeated Snell with a very fast burst on the back straight. After that Snell was wise to this tactic and had beaten the Jamaican in subsequent races. Still in 1961, Kerr almost beat Snell in Dublin, when he used the same tactic that had worked before and once again caught Snell napping. Snell had to really work to catch Kerr and was level at 800 and ahead at 880. They had both clocked 1:46.4 for 800 and Snell ran the fastest 880 of the year with 1:47.2.

1962 European Championships

1962 European Championships Belgrade, Yugoslavia, September 12-16 800Ranked third and second in the world in 1960 and 1961, Paul Schmidt (31) of Germany was the 800 favorite. And he had looked good in winning his semi-final. His compatriot Manfred Matuschewski (23) also had good credentials, with a 9th place world rankings in 1960. Further, both German runners had been Olympic finalists in Rome, placing fourth and sixth. The two Russians, Krivosheyev and Bulishev, also looked like possible medalists. As well, Ireland’s Derek McCleane was considered to have a chance (his talented team-mate Noel Carroll was eliminated in the first round).

1964 Olympic Games

1964 Olympic GamesTokyo, October 10-24 800There was much speculation over the fitness and intentions of the current 800 WR holder and Olympic champion Peter Snell. Unlike his rivals, he had not raced in Europe over the summer. Further, he had run only 1:48.5 in the earlier New Zealand summer. He told the press that the 1,500 was his main goal, so some doubted whether he would run the 800. And Snell was giving nothing away as to his fitness or his plans. In fact he was not sure himself about the 800. He had trained incredibly hard over the New Zealand winter, at one stage averaging 100 miles a week over a 10-week period. This distance training was followed by a sharpening period. But this was all done in the New Zealand winter, so he was unable to run any fast time trials. Any concern over his 800 speed was eradicated soon after his arrival in Tokyo when he ran a 1:47.1 time-trial. This convinced him that he could do both the 800 and 1,500.

1966 Empire & Commonwealth Games

1966 British Empire & Commonwealth GamesKingston, JamaicaAugust 4-13 880 Three of the top four finishers from the Tokyo Olympic 800 final were in the field. George Kerr, running in front of his home crowd and finally running in a major 800 race without Peter Snell, looked like a good bet for the gold. But the younger Kenyan Kiprugut was another favorite after his impressive semi-final. And then Bill Crothers, who had looked so good finishing second in Tokyo, was fancied by many pundits. Finally there were two Australians, Ralph Doubell and Noel Clough, as well as the fast-improving Brit Chris Carter.

See all 1960s articles

1970s

1970 Commonwealth GamesMeadowbank Stadium, Edinburgh, Scotland, July 17-25 There were two big changes from the previous 1966 Games in Jamaica. First, the distances were metric for first time. Second, the track was a synthetic all-weather track. No more cinders! 800Olympic Champion Ralph Doubell of Australia was the clear favorite. In the previous Commonwealth Games he had been sixth. Another hopeful was Benedict Cayenne, who had finished 8th behind Doubell in the 1968 Olympic 800 final. The Trinidadian had run a fast 1:46.83 in the semifinal.

1971 European Championships

1971 European ChampionshipsAugust 10-15 Helsinki, Finland The Finnish people had waited a long time for another Paavo Nurmi to raise their patriotic spirits. The flamboyant 5,000/10,000 double of Juha Vaatainen was thus hugely appreciated, especially since the location was the Finnish capital. He was head and shoulders above anyone else as the star of the meet for the running events. 800There were two outstanding athletes in this event: the returning champion Dieter Fromm from East Germany and Russian Yvgeniy Arzhanov, who had been undefeated in 33 races since his fourth-place finish behind Fromm in the 1969 Euros. These two runners were the same age, having been born within one day of each other in April 1948.

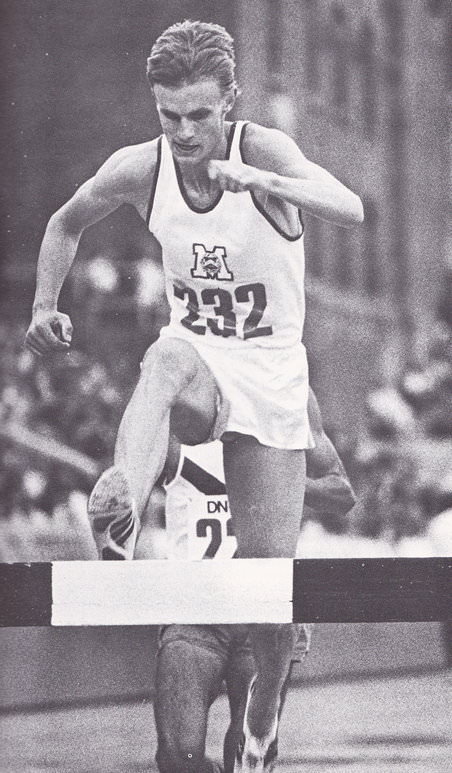

Anders Garderud Profile

Anders Gärderud Profileb. Aug. 28, 19466’1” (1.86 m) 154 lbs (70 kg) The story of Anders Gärderud is a story of promise fulfilled. It’s also a story of setbacks and of the need for a radical reassessment of a running career. Gärderud has been Sweden’s greatest runner since Andersson and Hägg. Thirty years after these two great runners had rewritten the record book for 1,500 and the Mile, he broke the world Steeplechase record four times over a four-year period, reducing it an amazing 12.6 seconds. And he capped off his career in the best way possible with an Olympic gold medal in a world-record time.

Clarke v Keino v Stewart v McCafferty v Rushmer

Clarke v Keino v Stewart v McCafferty v Rushmer5,000, Commonwealth Games, 1970Meadowbank Stadium, Edinburgh, Scotland Great Races # 22 Prospects This 5,000 race had all the qualities of a Great Race. It took place in a major games, it fielded some of the world’s finest middle-distance runners, it recorded four of eight all-time fastest clockings, it involved some intriguing tactics and it ended up with a very exciting last two laps. Roberto Quercetani considered that this race had “hottest finish in the history of the event.” (Track & Field News, July, 1970)

David Moorcroft: Profile

DAVID MOORCROFT PROFILE born 1953 David Moorcroft with his wife Linda and his coachJohn AndersonHis brilliant and stunning 5,000 world record in 1982, which knocked 5.79 seconds off the previous mark, has obscured David Moorcroft’s fine competitive record in his long running career. True the English runner did not achieve Olympic glory, but he did win two Commonwealth golds (1978, 1,5000 and 1982 5,000), a European bronze and a European Cup title (5,000 in 1982). In the years 1975 to 1982 he was rarely beaten when he was in top shape.

See all 1970s articles

Pre-1940s

With his talents, American miler Bill Bonthron could have conquered the world. He had strength, speed and a tenacious competitive drive. But while he performed brilliantly in his own country and even set a world record for 1,500 in 1934, he made little impact on the international scene and never competed in an Olympic Games. Following the traditional amateur conventions of his time, Bonthron planned his athletic career for just the four years of his university education. Once he graduated and married, his priority was his job as an accountant and he announced his retirement from running in 1934. Although he later broke with convention and continued to train seriously in his spare time, he never regained the form of his university years and failed to qualify for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He did make one European tour in his graduating year, but failed to live up to the reputation that had crossed the Atlantic before his arrival.

Glenn Cunningham

Glenn Cunningham Profile1909-1988 The life of 1930’s American miler Glen Cunningham has now become part of American folklore. It is the story of a young Kansas boy of pioneer farming stock who faced adversity with courage and determination to become a world-famous hero. This story, as it grew into folklore over many printed versions, has often been embellished with fictional details. However, the actual facts are powerful enough. When just seven years old, Glenn Cunningham was badly injured by a woodstove explosion that killed his brother. He spent over a year recuperating upstairs in his parent’s home before he was able to venture outdoors. His legs were so badly burned that it took him more than six months to stand, yet alone move. Yet through determination and self-discipline he learned to walk and then to run, eventually becoming a world-class runner.

Glenn Cunningham v Luigi Beccali v Jack Lovelock (1936)

The three favorites for this Olympic final were all reaching the climax of their careers. Luigi Beccali (29) of Italy had broken the WR for 1500 in 1933; he was also the reigning Olympic and European 1,500 champion. American Glenn Cunningham (25) was the current WR holder for the Mile, and he had been fourth in the 1932 Olympic 1,500 final. New Zealander Jack Lovelock (26) had set a Mile WR in 1933 but had not subsequently run as well. Still, a recent 3:01 time-trial over 1,200 showed he was back to his best form. These three great runners knew each other well from previous encounters on the track. Beccali had the best record, having beaten Cunningham once and Lovelock twice. Cunningham had beaten both men once, while Lovelock had beaten Cunningham three times. All three were known for great finishing kicks, so it promised to be a tactical race.

Jack Lovelock

PROFILE: JACK LOVELOCK 1910-1949 An Olympic champion and Mile WR holder, this New Zealander dedicated himself to becoming a complete runner. He applied a professional attitude to an amateur activity. According to Jerry Cornes, the President of Oxford University AC when Lovelock arrived there in 1931 as a Rhodes Scholar, “Lovelock…tried hard to know himself and was single-minded in his efforts to eradicate his weaknesses and to exploit the best in his mental and physical make-up. He was a pioneer in the analytical study of the one-mile and 1500-metre races.” Cornes, himself a fine runner and Olympian, went on to say that Lovelock “contributed in no small measure to what I will always regard as the final achievement—Bannister’s breaking of the ‘sound barrier’ of the four-minute mile.” (Quoted in Norman Harris, The Legend of Lovelock, p.9) Indeed it is interesting to compare Lovelock with Bannister: both developed their running careers while training to be doctors, both studied at St. Mary’s in London, both were highly strung, and both broke the Mile world record.

Jean Bouin v Hannes Kolehmainen

Olympic 5,000, Stockholm 1912Great Races #2 This great race was contested by the two leading runners of the time; both were considered almost unbeatable. Their superiority over all other runners was huge. And in the heat of this race the WR was decimated by an unbelievable margin.Frenchman Jean Bouin, 23, looked more like a boxer than a runner. He was thought to be overweight but said, “I haven’t got an ounce more fat to lose.” Bouin relied mainly on enthusiasm and was not considered hugely talented. But he was tough, making his name in cross-country. He had been national champion since 1909, and after running second in the 1909 International CC race, was the international champion for the next two years.