Profile: Roger Bannister

b. 1929

Roger Bannister’s name is synonymous with the four-minute mile. Why was he the first to break through this psychological and symmetric athletic barrier of four laps at a minute each? There were certainly some before him who were physically capable of running a mile under four minutes. Of course conditions had to be right and there had to be some pace-making help, but there also had to be the strong belief that it was possible. This strong belief was surely lacking in some of the early attempts—by the likes of Andersson, Haeg, Santee and Landy. That the four-minute mile was a psychological barrier can be seen in the veritable avalanche of sub-fours in the years immediately after Bannister’s epic run.

There is no doubt that Bannister was a gifted runner. He won a junior cross-country race at the age of 12 on the training of two 2.5-mile runs a week. Bannister modestly denied he had specialtalent as a schoolboy: “I am sure that I was not a better runner than the others, in the sense of having more innate ability. I just knew I had to win for the sake of peace.” (First Four Minutes, 32) This “peace” was what he needed among his peers so that he could work at the things that interested him, especially school work. He was then moved to a London school where there was no running at all. However, Bannister continued to develop stamina through long bike rides.

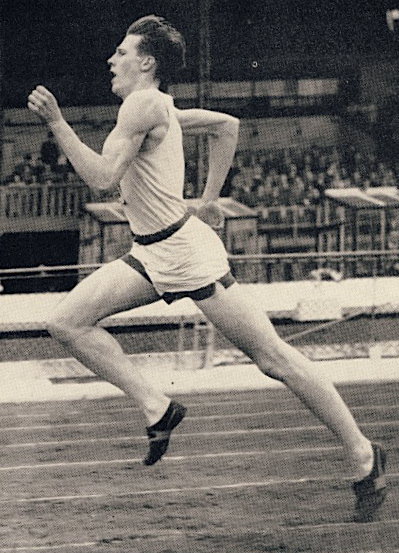

|

| Running in Oxford colourswhen 20. |

Bannister had a pivotal experience the year before before he went up to Oxford at the age of 17. He was taken to the White City by his father to see Sydney Wooderson (see Profile) run against Arne Andersson (see Profile) of Sweden. The example of Wooderson fired his “schoolboy dream” to become a runner. He started on this path with the Oxford Freshman’s Mile, placing second in the modest time of 4:53—the first time he had ever worn spikes. That first year he trained on Wednesday and raced on Saturday.

The next spring (1947) he ran for Oxford at the White City and won the mile in 4:30. In June he improved to 4:24. At this point, he started to think about needing a coach but was unable to find anyone suitable. He thus became self-coached. In November of 1947 Bannister was invited to be a “possible” for the 1948 OG, but with great maturity and foresight he declined because he believed he was not ready for international competition. In the Olympic year he improved to 4:17 and watched the Olympic competition from the stands: “By the end of the Games I was restless and anxious to compete myself. But there were four years to wait before my chance would come at Helsinki in 1952.” (FFM, 79)

After running 4:11 and a 1:52.7 800 in the USA in 1949, Bannister focused on the 800 in 1950. His season culminated in a fine third place in the European Championships. It was his first experience of major championships, and he considered himself “ill prepared.” Nevertheless, he led the final into the finishing straight before John Parlett and Marcel Hansenne passed him. He was only 0.2 away from a gold and had the same time as Hansenne. Afterwards, Bannister felt he had the tactical ability for big races but lacked “the strength to make use of a good position.” (FFM, 102)

After a season of competing all over Europe, Bannister badly needed a break. Sometimes he would go mountaineering for relaxation; this time he hitched alone in France, Switzerland and Italy.

Banister now had two years to prepare for the 1952 Olympics. He decided to use 1951 to get experience: “I would run in as many first-class meetings as possible….to travel widely…so that I could get used to changes of food and climate.” (FFM, 108) After spending Christmas in New Zealand and running 4:09.9, he ran 4:08 in the USA and 4:07.8 to win the AAA title. By then he was exhausted and took a Scottish climbing-vacation. Late in the season he ran a 1,500 PB in Belgrade (3:48.6).

The 1951 season underlined the fact that racing put him under “tremendous nervous strain.” (FFM, 138) So in his Olympic preparation he decided not to race cross-country. He trained mainly on his own after work round the Harrow School cricket field. “I never ran for more than half an hour, never timed myself with a stop watch.” (FFM, 138) This unconventional solitary preparation created a furore in the press.

The furore increased when Bannister severely curtailed his competition in the early summer, not even defending his AAA Mile title. “I knew I must store enough nervous energy to explode at the right moment," he wrote. "I could not afford to squander preciously hoarded nervous and physical reserves beforehand.” (FFM, 141) So he ran a low-key 800 as his first race in May (1:53) and then a 4:10 mile where he led all the way. Next he ran good time-trials over 1320 (3:01.6) and 660 (80.2). At the AAAs he won the half mile in 1:51.5, an effort that didn’t drain his reserves. His best pre-Olympic performance was a 3/4 time-trial in the “unbelievable” time of 2:52.9, which was 3.7 seconds faster than the unofficial WR.

|

| 1,500 Final, 1952 Olympics. A tired Bannister (177) is in a perfect position with less than 100 meters to go. Lueg leads from winner Barthel and McMillen. |

Then came the blow. It was announced that there would be an extra round in the Olympic 1,500. That meant three races in three consecutive days. Bannister recalls reading the news and realizing he just hadn't prepared himself to run three hard races in three days. Taking this attitude into the Games, he could manage only fifth in the semi-finals, finishing “blown and unhappy.” (FFM,156) Clearly over-stressed and expending the valuable nervous energy he had learned was essential to his success, Bannister was aching in his legs and unable to sleep on the eve of the final. He said he “hardly had the strength to warm up.” (FFM, 158) But when the race began he was fine, keeping out of trouble because he was “too tired to struggle.” Nevertheless, he managed to move into second place with 200 to go, “perfectly poised for my finishing effort.” (FFM, 158) But there was no energy left. He was unable to pass the leader Lueg and was passed himself by Barthel and McMillen. Finishing fourth, he had to grab Lueg to avoid falling on to the track: “I had never known such exhaustion.” (FFM, 159)

With his hospital work becoming “more pressing” Bannister now had to decide whether to retire or continue. After two months’ deliberation, he decided to give it two more years and work towards the 1954 European and Empire Games. That would also be the year of his medical finals. One big factor in this decision was his desire to prove that his training methods were correct.

He trained even harder in the winter of 1952-3, intensifying his interval training. He was also thinking of the four-minute mile, especially when he learned that Landy had run 4:02. Refreshed from an Easter break in the mountains of Wales, he ran a promising 3:01 time trial at the end of March. This was part of his build-up for a fast Mile at Oxford in May. In this race Chataway did the pace-making, taking him through in 61.7, 62.4, and 61.1. Then Bannister took the lead and ran 58.8 for the last lap to record a new British record of 4:03.6. He later wrote that “This race made me realize that the four-minute mile was not out of reach.” (FFM, 173) He improved to 4:02.0 not long after, but this time was not recognized as a record because the meeting was not an official one. Bannister went on to run well in 4x1,500 relays, and he won the AAA title in 4:05. Overall, 1953 was his best season for fast times.

So his winter training for the 1954 season began with great expectations. For the first time Bannister started to train with others. He considered this a “great change.” He trained in his lunch break with friends and then was persuaded to join in some sessions with coach Franz Stampfl, who was working with his friend Brasher. Bannister did his hardest sessions with Stampfl, running with Brasher and Chataway. They ran 10x440 “several times a week,” starting with 66 seconds in December and getting down to 61 in April. Then they stalled; they couldn’t get their times lower than 61. So Brasher and Bannister took a short mountaineering holiday. Back on the track they immediately dropped their 440s down to 59. Then Bannister started to taper his workload. April time-trials over 1320 (2:59) and 880 (1:54) showed he was ready for a fast Mile.

|

| The famous photo of the finish of the first four-minute Mile. |

In fact he was ready for a sub-four-minute Mile (see Great Races #8). Careful preparation and tactical planning under Stampfl’s guidance all came together. Still, Bannister’s great intelligence cannot be underestimated; it was an essential ingredient of his successful sub-four. In consultation with Franz Stampfl, Bannister arranged pacing by his colleagues Chris Brasher and Chris Chataway. Brasher was to take the first two laps and Chataway the third at least. Although a competitive race, this attempt on the four-minute barrier was openly based on two “rabbits.” After some worries about blustery conditions, Bannister decided the attempt was on. He was “towed” around to perfection, passing the bell in 3:00.7. An added bonus was that Chataway managed to maintain the pace round the next bend, leaving Bannister only 330 yards to run alone. It was a close call: 3:59.4.

Bannister achieved this athletic “milestone” while holding down a full-time hospital job. A most careful training program had enable him both to train effectively and to meet the requirements of his job. As well, he had learned that he needed breaks from the regimen he had set up. In short, he had trained his body and his mind for his great achievement.

Now world-famous, Bannister had to deal with the fall-out from his four-minute mile: a flurry of press encounters, a meeting with Prime Minster Churchill, and even a “goodwill tour” to the USA for the British government, which had some people questioning his amateur status. Not surprisingly, Bannister soon felt that his running was “in the doldrums.” He lost an 880 to Jungwirth and then ran a very disappointing 2 Miles. On top of this came the news that Landy had run a faster Mile (3:58) in Finland.

The news of Landy's fine run jolted Bannister back into hard training. He now had just two months to prepare for the Empire Games Mile race against Landy in Vancouver. Knowing that Landy could be taken in a sprint finish, Bannister trained and raced accordingly. His AAA Mile win with a 53.8 last lap must have worried Landy. To counter Bannister finishing kick, the Australian front runner would have to ensure he had a large lead for the last lap in Vancouver.

|

| Bannister charges by Landy in the Vancouver Empire Games Mile. |

The epic Vancouver race between Bannister (with a cold) and Landy (with a gashed foot that had been stitched) is told in Great Races #9. As expected Landy pushed the pace hard in the early stages. He had a small lead after the first lap (58.2). In the second lap this increased on the back straight to 15 yards, but by the halfway mark (1:59.2), Bannister was only 10 yards behind. On the back straight, Landy’s lead was down to five; at the bell, Bannister was on Landy’s shoulder. Bannister had used a lot of energy catching Landy on lap three, which he ran in 59.6. Still, after trailing Landy for the next 330 yards, he had enough in reserve to burst by with 110 to go. Although slowing in the last 70, Bannister held on to win by 0.8 of a second in 3:58.8. This victory capped a wonderful eight-year career—a career that had spanned his university degree and his medical training. Now a qualified doctor, the first four-minute miler decided to retire and focus on his profession. Has any runner retired on a higher note?

5 Comments