PROFILE: JACK LOVELOCK

1910-1949

An Olympic champion and Mile WR holder, this New Zealander dedicated himself to becoming a complete runner. He applied a professional attitude to an amateur activity. According to Jerry Cornes, the President of Oxford University AC when Lovelock arrived there in 1931 as a Rhodes Scholar, “Lovelock…tried hard to know himself and was single-minded in his efforts to eradicate his weaknesses and to exploit the best in his mental and physical make-up. He was a pioneer in the analytical study of the one-mile and 1500-metre races.” Cornes, himself a fine runner and Olympian, went on to say that Lovelock “contributed in no small measure to what I will always regard as the final achievement—Bannister’s breaking of the ‘sound barrier’ of the four-minute mile.” (Quoted in Norman Harris, The Legend of Lovelock, p.9) Indeed it is interesting to compare Lovelock with Bannister: both developed their running careers while training to be doctors, both studied at St. Mary’s in London, both were highly strung, and both broke the Mile world record.

|

Lovelock came to Oxford from New Zealand in 1931 with a personal best in the Mile of 4:25.8. Within two years he set a world record of 4:07.6. At first he had to play second fiddle to Jerry Cornes, who went on to win the silver medal in the 1932 Olympic 1,500. In fact, in his first year at Oxford he did not improve his Mile time. But in 1932, after improving gradually to 4:20.8 in the early season, Lovelock had a big breakthrough with 4:12.0 in a match between Oxford and the AAA. This time was less than three seconds outside the world record. Five weeks later, after running a fast 3:02.2 3/4 Mile, he ran 4:14.4 to place second behind Cornes in the AAA Championships.

Not surprisingly New Zealand chose him for the Los Angeles Olympics. And although he made the final and led some of the race, a long competitive season caught up with him. Lying fourth with 200 to go, he faded badly to finish a distant seventh.

Lovelock’s focus for 1933 was a big Mile race in the USA against Bill Bonthron. His ability to prepare effectively for a big race was evident for the first time. After a warm-up race in which he almost equaled his PB with 4:12.6, Lovelock ran a perfect race in tracking Bonthron until 150 to go and then blasting past his rival to a new world record of 4:07.6. Lovelock had peaked for this one race, but he managed to peak again two months later in September. The race he focused on was the 1,500 in the International Student Games in Turin. Although he ran very well and came very close to the metric equivalent of his Mile world record (3:49.8), he lost to the Italian Olympic champ Beccali. Eight days later in Paris, he showed he could run more than one fast race when peaking, winning another 1,500 in 3:52.8.

|

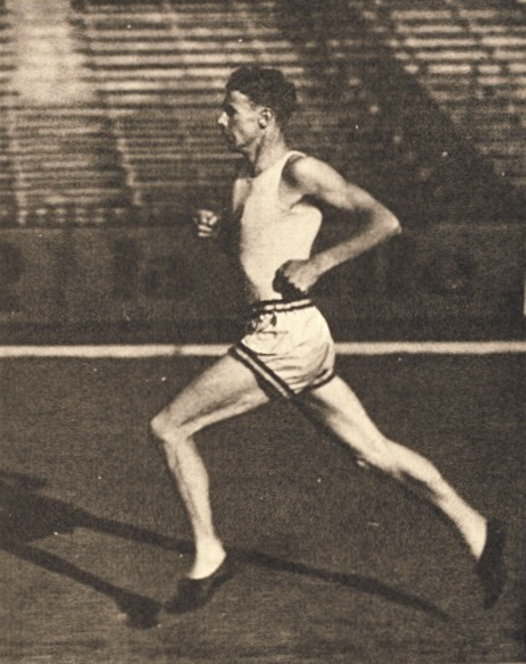

| Lovelock's compact and efficient style. |

There was a slow start in 1934 for two reasons. First he had a knee operation; second, he was completing his Oxford studies. He placed only third in the Southern Championships (4:15.2) but won the AAAs in a slow 4:26.6. Then in a match against Princeton and Cornell, he beat the new world-record-holder Bonthron in 4:15.4. Following these build-up races, he peaked perfectly for the Empire Games Mile. After an erratic start to the race (59.5, 2:06), Jerry Cornes took over and led through three laps in 3:12.5. Cornes was still in front on the last bend, but coming into the straight Lovelock powered ahead and won by six yards from Wooderson in 4:12.8. His season ended early in August with a few low-key European races prior to starting work as a junior doctor at St. Mary’s Hospital in London.

As a hard-working doctor, Lovelock had to adapt to a very different life with little spare time for running. He started his 1935 racing year in May, during which his Mile times came down from 4:36 to 4:13. He was peaking for the Mile of the Century in Princeton, where he was up against Bonthron (now holder of the WR for 1,500) and Glenn Cunningham (now holder of the Mile WR, which Lovelock had previously held). Again he showed that he could produce his best time of the year when it counted. The huge press build-up for this race must have affected Lovelock, but he showed he could deal with the pressure.

From the start, he tracked Cunningham, who after a slow 64.9 first lap, accelerated into a energy-sapping 60.4 second lap. Bonthron found the third lap hard and dropped back a little while Lovelock stayed close to Cunningham. A 63.2 lap brought the American to the bell in 3:09.1. But Cunningham was soon spent, and he slowed on the back straight. Lovelock fought the temptation to go early and waited until past the crown of the last bend to make his effort. He “glided” easily down the final straight to win in 4:11.2.

Lovelock took a four-month break in the 1935-6 winter, focusing on his new job and winning the Inter-Hospitals featherweight boxing title. Serious training began only three months before the Olympics. Worried about his finishing kick, he was now considering running the 5,000 rather than the 1,500. Still, his mile times began to drop: 4:53, 4:42, 4:30. Avoiding top competition, he tried a three-mile race, running 14:20 with a 59-second last lap. A week later he was second in the Southern 880 with 1:56. In the British Championships Mile he was outsprinted by Wooderson. But by now he was training very hard and just before the Games ran a confidence-boosting 3:01 for 1,200. He felt he was ready for the Olympic 1,500.

|

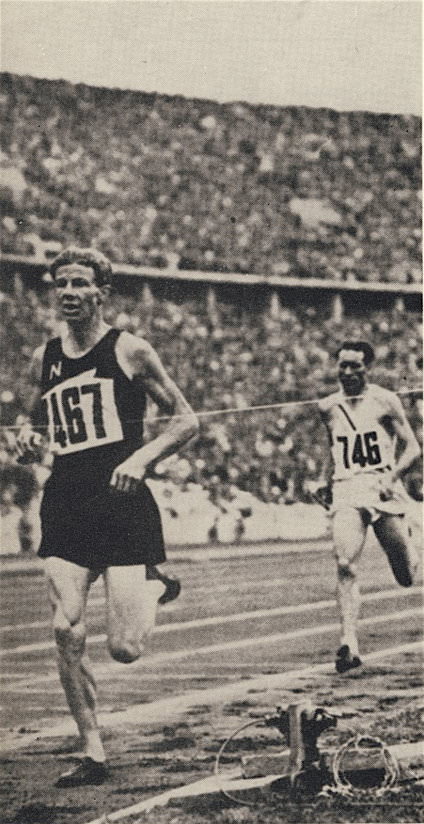

| Olympic 1,500 final in Berlin:Lovelock breasts the tape. |

The Berlin Olympics were a complete triumph for Lovelock. His winning time of 3:47.8 lowered the World Record by a full second. He ran a perfect tactical race, pouncing into the lead with 300 to go and opening up a 3-4 meter gap that neither Cunningham or Beccali, his two great rivals, was able to close. (See Great Races #3)

This perfect race should have been the last of his career, but he agreed to one more race—at Princeton, where he had run so often before. It was of course an anticlimax after Berlin, but he still managed to run his second fastest mile (4:10.1). He was denied victory by an inspired San Romani, a 19-year-old who had finished fourth behind Lovelock in Berlin.

Bannister, who was to study at the same Oxford college and work at the same hospital as Lovelock did, met the New Zealander (“a very neat runner”): “He made one remark to me at dinner which I thought very important, about choosing the right moment for the unexpected finish.” (Norman Harris, The Legend of Lovelock, pp. 9-10) Bannister used Lovelock’s advice to good effect on several occasions.

Sadly, Lovelock did not live to witness the Englishman’s classic victory over Landy. A 1940 horse-riding accident had badly affected his sight; from then on, he suffered from double-vision and an inability to judge distances. Nine years later, on his way home early because he felt dizzy, Lovelock fell under a New York subway train. He was eight days short of his 40th birthday.

Leave a Comment