John Whetton Profile

b. 1941

Few world-class runners have been able to exploit their physical potential to the extent that John Whetton did in the 1960s. Not as physically gifted as some of his rivals, this British runner nevertheless managed to achieve a competitive record that few have equaled. His achievements on the track were the result of careful planning, dedicated training and intelligent race strategies. Ian Stewart called him “the bloody cleverest” 1,500 runner in Europe. Whetton’s greatest victory was in the 1969 European 1,500. He also ran a fine fifth in the 1968 Mexico City Olympic 1,500. But perhaps his competitive ability came through most clearly indoors. He was unbeaten indoors in the UK and Europe throughout his career and won the European 1,500 three times in a row (1966-1968). Such was his indoor reputation that he was known as the King of the Boards.

Mansfield Schoolboy

John Whetton showed promise as a schoolboy. His Nottinghamshire father had represented his county in cross-country. “From his encouragement,” Whetton recalls, “I got fixed into this running thing.” As an twelve-year-old at Mansfield's Brunts Grammar School, he had started running primarily to avoid ball games. He vividly recalls how this happened: “One day on the football field, I saw a number of older boys running up from the sewage works covered in mud. They were involved in cross-country. The following week I opted to do cross-country instead of football. I beat the older boys too.”

From the start, he was competitive academically and athletically. While at grammar school he won the 880 in the LAC Schools meet and won the 880 English Schools title at 17 and 18. In his first victory at 17, he broke the meet record with 1:55.6. And he also achieved academic success, earning a place an Manchester University.

Serious training began when he was 17. At a coaching weekend in Mansfield he met Bill Coyne from London. At the end of the weekend, Coyne offered to coach him: “I was overwhelmed and said yes. But the coaching was mainly by letter. Occasionally, when I saw him, he put me through some tough sessions in Regent’s Park in London. But coaching by mail is not very good.”

University Days

Before he went to university in 1960, Whetton was lucky enough to be taken to the Rome Olympics by his club President, Dudley Clarke and some friends: “I was standing in the stadium close to the start of the 1,500 and saw the likes of Elliott and Jazy on the track.” While in Rome, Whetton celebrated his birthday and was toasted by Clarke: “You’re 19 and here’s a toast to your being in Tokyo in four years’ time. And we will be there to watch you.” And they were, too!

Whetton had a lucky break as soon as he got to Manchester University in 1960: “I wanted to go there because of my athletics; I knew they were producing good athletes. The first week there I met this guy call Ron Hill. [See Profile] I’d never heard of him. He was three years older and was starting a Ph.D. in Textile Chemistry. We trained together 2-3 times a week. I helped him with his speed; he helped me with endurance, which was very, very important.” Hill and Whetton trained on the university track and playing fields in Fallowfield, where Hill lived: "We had this very special session together, sort of ritual. Three times every two weeks we did 20x440 with a 220 jog recovery. We did that in all weathers--rain, snow or fog. We took turns leading, but I would beat Ron on the last two. (laughs) We also did fartlek round the perimeter of the playing fields. On Sunday mornings we did an 11-mile run on the roads. That was the toughest slog.”

While at Manchester University he benefited greatly from working out with Hill: “I trained with Ron for three years. He was definitely a major influence.” Confirmation of Whetton’s increasing strength came with a 12-second victory in the 1962 Inter-Counties Junior Cross-Country. On the track he showed great speed improvement with an indoor victory over Derek Ibbotson to win the 1963 AAA Mile title in 4:13.3. And later that year he won both the British Universities Mile and the Midlands Mile titles. His good form earned him his first international race in France against the legendary Michel Jazy. “He left me standing, of course,” Whetton says with a chuckle.

But his best 1963 race was yet to come. The victory in the British Universities Mile earned him a place on the British team for the World University Games in Brazil. In what was a tactical race, Whetton “burst through the field to win.” (Times, Sept. 17, 1963) This victory in 3:49.5 was by far his greatest so far, especially since the field included Jozef Odlozil and Witold Baran. So 1963 was definitely his “emergence” year. But he wasn’t thinking of making the Tokyo Olympic team: “I hadn’t even broken 4:00 [for the Mile].”

Loughborough Year

| The day the Tokyo Olympic team was announced in 1964. From left: Lynn Davies, John Whetton, John Cooper, Ann Packer, Robbie Brightwell. |

He improved remarkably after the 1963-64 winter. “It was going to Loughborough that made the difference,” he explains. “I was doing lots of sports there—rugby, football, swimming, gymnastics. After two terms of all that on top of my running, I was knackered. I wasn’t racing at all well. I thought I was finished. But come the summer, when things at Loughborough died down, suddenly I blossomed. All that hard work gave me an incredible grounding.”

Loughborough gave him another good break: he met Coach Geoff Gowan. Gowan coached only two athletes: Robbie Brightwell and John Cooper. “In the spring he asked me if I’d like to join them at a week’s session by the sea in Norfolk. I accepted. Also there were Ann Packer, Mike & Mary Tagg, and Richard Simonsen from Norway. We had some amazing sessions on the beach and in the sand dunes. Things then started to happen for me.” Brightwell, a 440 specialist, was also at Loughborough; he helped Whetton as a coach too: “Speed was his thing, and I learned a lot more about speed-endurance from him. He was also a great motivator, like Geoff.”

Whetton called the hard work at Loughborough and his training under Gowan “an electric combination.” Soon he was running at an international level: “I ran a 3:42.7 PB to win the 1,500 at the British Games, beating Mike Wiggs. It was an eight-second improvement. Then in the Emsley Carr Mile I beat 4:00 in finishing second to Baran (3:58.9). That put me on the Olympic team.” It looked like Dudley Clarke’s 1960 toast was going to be fulfilled. And there was another auspicious comment that came Whetton’s way from Gowan: “He put me through a session that he said would replicate what I would have to put up with in Tokyo. He said, ‘When you get into the final”—not ‘If you get in the final!’”

Tokyo Story

|

| Tokyo 1,500 final. Whetton follows John Davies after leading for a lap. Baran, Burleson Snell, Bernard, Simpson, Odlozil and Wadoux follow. |

The prophetic “we’ll-see-you-in-Tokyo” birthday toast four years earlier, as well as Geoff Gowan’s presumption that Whetton would reach the Tokyo final, came true. He ran a PB of 3:39.9 in the semis to reach the final as the fastest loser. Such prophecies would appear flippant to many people, but not to Whetton. Psychological preparation for big races was an important weapon in his competitive arsenal. He always had a race plan and employed visualization before it was a common practice. “I am nervous before big events. I have to be alone for two hours resting. I cannot sit in the stands watching others compete before a big race. When I am nervous, I am ready for all comers.” And “big events” were Whetton’s specialty; he always performed well in them. So how did he do it? “It’s my competitive nature. If I ran a race on a local track, I ran as hard as I could, but I couldn’t get the time. But come an important competition—wow!—I was there.”

So though still young and inexperienced, Whetton came up with the goods in the Olympics, when it really counted. But the effects of his 3:39.9 PB were still there for the final: “Two days later I had still not recovered from the semi-final. I was sluggish and very tired.” (Alastair Aitken, Highgate Harriers.org) Nevertheless, he was still in contention when the leaders passed the bell. “The final was a strange affair. Nobody wanted to take the lead. I thought it was shameful with 80,000 people watching the race. So I took the initiative and led for at least a lap. Then John Davies took over. Come the bell, it was all starting to happen.”

|

| The encounter with Snell (3rd), who is putting out his right had in front of Whetton to escape from a box. |

On the crown of the penultimate bend, Whetton experienced the roughness of top-class competition: “I overtook Peter Snell; he was boxed. He put his right hand out and said, “Can I come?” I didn’t respond; I wasn’t going to let him come. He was desperate, so he barged me. He knocked me out into lane three and got out. He was away.” Of course, Snell went on to a convincing victory. But Whetton had more trouble on that bend: “As I was coming back into the first lane, I then got entangled with [team-mate] Alan Simpson. That upset both of us in terms of momentum. When you are tired at a crucial stage of the race and your legs are buggered, it’s difficult to get going again. Had we not got entangled, I reckon that Alan would have finished second. I really do believe that. I’d have probably finished fifth.”

As it was, Whetton was eighth in 3:42.4. This time would have been a PB before the Games, but he was 4.2 seconds behind Snell. Today, looking back almost 50 years, he can laugh about the barging incident: “In his book No Bugles, No Drums, Snell wrote, ‘John Whetton, with the manners of a true Englishman, obligingly moved aside.’ (Laughs) I think that’s his apology to me! He’s such a nice man.”

From Student to Teacher

On returning to England, Whetton entered the work force. His student days were over; he was now a school teacher. This new life had a profound effect on his athletic career: “It was only two or three years ago that I realized what was happening at that time. Today all our top runners are receiving financial support through the national lottery. They don’t work. They can eat, sleep and rest all day and every day. Looking back on my career, I now realize that my performances were impaired during school term time. I couldn’t devote enough time to training because of my work. But at the end of the long school summer-holidays, I reached a peak. So my best races were in late August and early September. Luckily this period coincided with major games.”

Whetton now calls this latter part of his career “an awful compromise.” That he continued at all says as much for his love of running as for his competitive ambitions. “I had the good fortune to live close to the huge Sherwood Forest, which had lots of tracks, pathways, hills, and valleys. Every hill was a challenge; I ran hard up them. It was a gift to have this natural environment. I have always believed it’s nice to look around and to smell the environment while running.”

|

| Whetton holds up the Wanamaker Trophy after winning the Mile at New York's Millrose Games. |

But the rigors of Whetton’s first year of teaching took the edge of his 1965 outdoor performances: “My running interfered with my job, and my job interfered with my work. When you want to be a world-class miler, it takes its toll on other things.” Whetton did win the Inter-Counties Mile in May, but later on he didn’t even make the final of the AAA Mile. Nevertheless, he was selected to represent the UK against Hungary in August, finishing second to Simpson. The Simpson-Whetton team became the most respected 1,500 duo in international team competition. But there was some flexibility with his job. In early 1965 he got leave to race indoors on the American circuit. And it was racing indoors that became his most successful activity over the next three years. Of course, he had already earned high credentials in this winter sport, having won the AAA indoor title Mile title in both 1963 and 1964 as well as other British events. These successes led, in January 1965, to an American tour. In New York he won the prestigious Wanamaker Mile in the Millrose Games (4:05.4). In Philadelphia he won another Mile in 4:06.8. Then back in the UK he won his third AAA title, beating Alan Simpson 4:06.3 to 4:06.4 for a UK All-Comers Record. His most successful indoor season so far finished with a victory against the USA, in which he beat Simpson (again) and Jim Grelle.

More Success Indoors

In January 1966 he was in the States again, this time to run against Jim Ryun in San Francisco. The great American miler handed him one of his rare indoor defeats. Whetton recalls he wasn’t in the best of shape for the race: “I was knackered. Flying all the way to San Francisco and trying to race at 3 am my time. I did amazingly well considering these conditions.” In fact he was very close to Ryun, who ran a fast 4:02.1. Whetton’s 4:02.5 was a British Indoor Record.

Whetton continued with yet another Indoor AAA Mile title and then went on to win the 1,500 in the first European Indoor Championships in 3:43.8. At this point in his indoor career he had won 26 of his 28 indoor races. How did he maintain racing fitness in the English winter? “The reason was that my winter training was based on quality work. The foundation of my training throughout the year was fartlek—in the woods, in the parks, fast and slow. Taking advantage of the hills and forests, I would do bursts of 100 to 500.That was the foundation; I’d got speed in the winter.”

Whetton also explained why he was so successful indoors: “First of all I had that fitness. Then I was always alert in races. Further, and this is important, I never ever wore spikes indoors. I concluded that the traction between rubber and wood was perfect. You didn’t need spikes. I wore road-running shoes. Toward the end I wore a pair of Puma marathon shoes designed by Ron Hill. The soles were wafer thin. They weighed hardly anything. Apart from footwear, I always ran close to the inside. If you run in lanes 2 or 3, you are losing many meters in a race as there are lots of bends. I tried to stick to the inside while always being in contention. I would take the lead just before or just after the bell.” Additionally, he had fast leg speed. “People said I had a sit-down style like Michael Johnson. So my center of gravity was low. That was advantageous going round tight bends.”

Again, the outdoor season was an anti-climax: “1966 was my worst year. I attributed that to hard physical work. I was building a house. Before I started building it, I was going well. Toward the end I was doing better. Although I didn’t compete in the Commonwealth or European Games, I ran in international matches before and after. But I was physically knackered.”

Mexico Ahead

With his house built, Whetton’s running improved in 1967. Indoors, he won the AAA Mile yet again and won his second European 1,500 title, this time beating his Tokyo opponent Odlozil. As the summer approached his thoughts began to focus on the Olympics just over a year ahead, and on the thorny issue of running at altitude in Mexico City. In May, he requested time off from his teaching job to attend a British altitude training camp at Fort Romeu in the Pyrenees: “They only allowed me time off without pay—miserable beggars! That was my first exposure to altitude—7,500 feet. I did well; I adapted well. I learnt to cope with the breathlessness, the hyperventilation. I decided I’d got to ignore it and just carry on and endure the pain in the legs. That was how it would be in a year’s time in Mexico.”

Back home he began to find his best competitive outdoor form. For the first time he started to beat his old rival Alan Simpson. And in September he ran a fast 3:57.6 Mile behind Keino. This good form gave him extra encouragement for his winter preparation for the 1968 season. And early in the new year he again showed good form indoors. By now, as the unbeaten King of the Boards, he was the target of every middle-distance runner. But he managed to maintain his unbeaten record, culminating in his third European 1,500 title in what he described as “the most nerve-wracking race of my life.” (Times, March 11, 1968) Running with a sore back and having just recovered from flu, Whetton had to run the race of his life to maintain his unbeaten record in Europe.

Neil Allen’s description of the end of the race illustrates Whetton’s intense competitiveness: “With 2 1/2 laps to go he decided to get away from the inhibiting proximity of Potapchenko and tried to take the lead. But to his surprise the little Spaniard, Jose Morera, shot ahead of him and up came the Russian again to block Whetton. Whetton now had to decide, as he passed the bell, whether to wait for the short final straight on the 182-metre banked board track or go on the final back straight. Wisely he chose the back straight, but it needed a supreme effort to pass first the Russian and then Morera and reach the last bend first by no more than a couple of strides. Whetton accelerated explosively, his short stride and his acute body angle whipping him round the turn. The Spanish crowd changed from roars of encouragement for Morera to applause for a consummate master of indoor racing.” (Times, March 11, 1968) Whetton had run the last 400 in 51.2 to maintain his unbeaten record indoors. Right after his victory, he announced his retirement from indoor competition: “The races were getting increasingly threatening because I had never been beaten in Europe. I became a bigger and bigger target. Everyone wanted to beat me.”

Now his focus was entirely on the Olympic 1,500 in August. Not only did he have to qualify for the British team but he also had to prepare for the altitude of 7,500 feet. His qualification wasn’t confirmed until the beginning of August. Despite winning the AAA Mile title earlier, he still had to finish in the top three in the Emsley Carr Mile. This he did with a convincing victory in 3:58.6. As for his preparation, he worked out a special program: “In my training, I tried to simulate what would be happening in Mexico City. I decided, as a physiologist, that I had to put my body in severe anaerobic respiration for long periods. Robbie Brightwell suggested doing back-to-back 100s. So three times every two weeks I did a session of 40-50x100, with 30 seconds between to slow down, turn around and start again. With as many as 50 reps, it was absolutely excruciating to put my body in anaerobic respiration for such a long period. But that was what it would be like in Mexico City.” Why did he choose 100-meter reps rather than say 200 and 400? “The longer reps would need longer recovery—I’d be slowing down. I wanted to go fast.”

Such ruthless training paid dividends: “When I arrived in Mexico City, it was really easy. I was going out with the distance men at 10-12,000 feet and beating them. In the pre-Olympic competition most runners went down a distance. I did the opposite and ran the 3,000. I was up against two top Mexicans, Juan Martinez was one of them. I just hung on. I was with them at the bell and took off on the back straight and won. That was the final piece of mental preparation. I wasn’t frightened of the altitude. I was confident.”

The preliminaries gave him even more confidence: “The heats and the semi were a piece of cake. Everybody was frightened of the altitude.” He now changed his goal: “My original ambition was to get into the final. But because of my training and racing, I was now after a medal. I knew I couldn’t get a medal if I wasn’t in contention. So I’d got to be with them. I didn’t know how I’d be feeling with 500 to go. Nobody knew.”

Going for a Medal

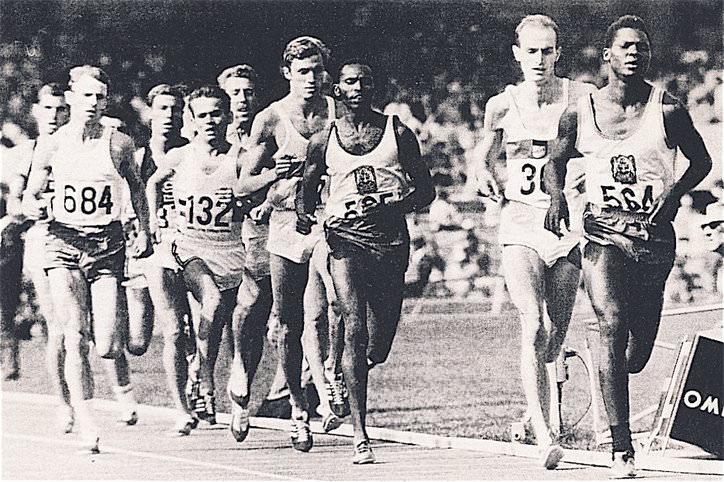

|

| Whetton well up (6th, on the inside) in the early stages as Jipcho blazes a fast pace. Norpoth, Keino and Tummler follow. |

The 1,500 Olympic final started dramatically as the Kenya #2, Ben Jipcho, set a blazing pace for his colleague Kip Keino. As Whetton put it, “It was bloody fast at the start.” Unlike West German Harald Norpoth, who was right on Jipcho heels, Whetton held back a little from what seemed like a suicidal pace. Nevertheless he passed 400 in under 58. Soon after this, a gap began to develop in front of Whetton as Jipcho, Norpoth, Keino and Tummler maintained Jipcho’s fast pace.

As they entered the finishing straight with just over two laps to go, Whetton made his big decision to close the gap in front of him and move up to the leaders: “I concluded I’d got to go with them. The 1:55.6 at 800 was the same time I ran at 17 when winning the English Schools!” At this point, he was in medal contention, up with Tummler and Norpoth and just a few meters behind Keino. Behind, Ryun was three seconds off the pace.

|

| One lap to go. Whetton is hanging on to fourth ahead of Ryun. "I learnt more about tenacity and my own personality than I'dever done before or since." |

In the 300 meters up to the bell, Keino managed to stretch his lead to 7m. Behind him Whetton was desperately hanging on to the Germans, while Ryun was closing fast on him. Round the penultimate bend, the two Germans got away, and Ryun managed to catch him. “I ran out of steam,” he recalls. At 1,200 Ryun and Whetton were clocked at 2:56, Keino having gone through at 2:53.4. It was now a matter of hanging on for fifth place, which he did: “It was the hardest race I’d ever had in my athletic career. I was put on a stretcher after. I was so exhausted, hyperventilating. In that race, in that 4-min period, I learnt more about tenacity and my own personality that I’d ever done before or since. I learnt about personal sacrifice, what your body can do providing your brain doesn’t give in. That gave me confidence for other things well outside athletics. If you want to do it, you can do it.”

Whetton had finished a surprising fifth in 3:43.8. (See Great Races #21) Yet again he had come through in a big race. He says he was “disappointed but pleased.” Disappointed at not getting a medal, but pleased that he had used the correct tactics and pushed himself to new limits. Times journalist Neil Allen aptly called his performance “gallant.”

Life After Mexico

Back home in Mansfield, Whetton settled down to another winter’s training. He continued with his speed-based Fartlek and raced as usual on the country. But he kept true to his retirement from indoor competition. Instead he focused on getting a good base for the 1969 outdoor season and the European Championships in Athens. In June he ran his fifth 4:00 Mile with a 3:59.2 victory. But following that, his performances were below par. In Los Angeles he was beaten into fifth by Marty Liquori, and back home he lost his AAA Mile title to Frank Murphy (“I messed up my race plan.”). Then in a home match against the USA he was beaten into third by two relatively unknown Americans, Mason and Brown. Clearly, his teaching duties were still affecting him at this time.

However, by the time the European Championships came round in the middle of September, he was in much better shape. But atypically he had lower expectations: “I was well-prepared, but I was getting to the end of my career. All I wanted to do was to get into the final and maybe in the first six." But once he qualified for the final, he wanted to win: “Almost right away I started working out my race plan. That was my mental rehearsal. My plan was to get into contention with two laps to go.” His new focus on winning was reinforced by an incident the day before the final. After offering condolences to a colleague who had just lost his father, he was told, “John, good luck tomorrow. You can win.” Whetton recalls, “That sort of psychological suggestion did something for me subconsciously.”

Whetton’s race plan went smoothly: “Like in the indoors, I wanted to stick to the kerb to save distance. It was one of those races where windows kept opening up for me. Runners in front of me would want to move out and avoid getting trapped. And I’d sneak in. Going down the back straight of the last lap, I was fourth or fifth. All the big boys were there: Arese, Szordykowski, de Hertoghe. Murphy was in the lead. Then with 200 to go I managed to nip through on the inside of Arese and de Hertoghe and move right behind Murphy.” Fortunately the Germans Tummler and Norpoth, who had both beaten him in Mexico City, were not in the field because of a West German boycott. Whetton’s main concern was the fast-finishing Irishman Frank Murphy, who had beaten him in the AAA Mile. Also dangerous were Szordykowski, Arese, de Hertoghe and Wadoux.

Whetton now waited patiently: “I was right behind him coming into the straight. That's where I always give my final kick. Gradually I eased up alongside him. All I could think of from that point was keeping my form. If you don’t, you lose. I kept my form and gradually eased past him.”

Whetton was now European 1,500 outdoor champion. He had only one tenth of a second margin at the tape, but that was enough. “The race went exactly to my plan every step of the way. In that respect it was one of the easiest races I've ever run. It was a European championship record, too." After this victory, the 5,000 gold medalist, Ian Stewart, paid Whetton a great compliment: “Old John is not the fastest 1,500 runner in Europe, but what he showed them in Athens was that he’s the bloody cleverest. That’s what it’s all about.” (Times, Oct. 24, 1969)

After his European success, Whetton was offered a professional contract by Henk Visser, who was hoping to start an indoor professional track circuit in North America. He told the press that he would consider the implications of the contract. Finally, several months later in May 1970 he announced he had turned down the offer because he didn’t want to become a full-timer on the circuit and because he was losing his competitive enthusiasm at 29.

One More Year

Nevertheless, he still had enough enthusiasm to “give it one more year for the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh.” With a new job as a lecturer in teacher training and his first child on the way, Whetton had been planning to retire at the end of 1969. But his European win had given him a boost.

After another hard winter of speed fartlek and cross-country racing, Whetton showed good form early in the track season, winning the Inter-Counties 1,500 with what Neil Allen called “a beautifully timed burst.” But his new job was now his priority, and he turned down a chance to run for his country against East Germany. Then he ran his second fastest-ever Mile in 3:57.7 for second place behind John Kirkbride.

The Commonwealth Games started well for him. He won his heat in 3:50.2. The final was dominated by Keino and Dick Quax of New Zealand. These two were soon out on their own and were 40m ahead at the bell. Behind them Whetton was fighting for the bronze medal with Brendan Foster, Peter Stewart and Ian McCafferty. Whetton was well placed coming into the final straight, but Foster powered by and managed to hold off a Whetton counterattack. And then right at the tape, Stewart edged by Whetton for fourth. Whetton’s time was 3:41.2, just 0.6 of a second slower than Foster’s time for third.

This was not the way Whetton usually performed in the last 100 of a race: “I should've got maybe the silver behind Keino. I had a bad race. I felt awful. After the race, I was on my back on the ground in a tunnel hopelessly in distress. It was worse than in Mexico City. The following day I drove home and found I was incubating flu. That's why I didn't run very well.”

After the race, he told the press, “It’s all over. I shall not run in any games again.” (Times, July 24, 1970) But he did race once more, in the IAC Coca-Cola Meet at Crystal Palace: “I broke four minutes, so I went out on a reasonable high. That was it: all done.”

Retirement

| Whetton's prized possession, a 1924 Rolls Royce. Itoriginally belonged to Rodman Wanamaker, the wealthy millionaire who established the Wanamaker Mile. Whetton won this race in 1965. See photo above. |

John Whetton spent for the rest of his working life at Nottingham Trent University, eventually becoming head of the Physiology Section of the Life Sciences Department. For twelve years he did no running, but then came the jogging boom. He began to write a weekly running-advice column for the Nottingham Evening Post. When the London Marathon started, Whetton set up marathons in Nottingham and Sheffield and a half-marathon in Doncaster. With all his involvement in marathons he decided to do one himself. After eight months of training he ran a 2:39 in the Bolton to Manchester Marathon. And six months later, at the age of 42, he improved to 2:22 in the London Marathon. He went on training: “I was now committed. I trained hard for 1985. It went well, but I got a chest infection two weeks prior. I thought I’d still go and jog, but I felt better on the morning of the race, so I went for it. I really suffered. My 2:25 time was good time in the circumstances, but the race psychologically destroyed me; I didn’t want to do another one.”

He still found one more outlet for his running--bloodhounding. After the ban on foxhunting, Whetton joined this new form of foxless hunting, becoming in fact the fox himself. He allowed himself to be chased by hounds as a fox would have been in the past. Of course, there was no “kill” if the hounds caught him. The worst he could get was a lot of licks and a lot of saliva. There was sometimes a little blood, but that came from encounters with barbed-wire fences and brambles. He was involved in bloodhounding for 20 years: “I enjoyed it enormously. It’s the freedom of running over fields and through woods. It’s incredible the feeling you get. You could run over fields where normally you’d get a shot up your backside from a farmer.”

Retrospect

Now 71, Whetton’s career is almost 50 years in the past. The memories are good. And he remembers with gratitude the people who helped him most with his running: Dudley Clarke, Bill Coyne, Ron Hill, Geoff Gowan, Rob Brightwell. Amid all his memories is one regret: “I wish I hadn’t found a job; I wish someone had kept me. I wish hadn’t had the problem of building a house. I needed more time to relax and focus on quality training.” He says he gained the most pleasure from his 1969 Euro 1,500 victory: “It was relatively easy; it went to my vision, exactly to plan.” He adds that he also got pleasure from the 1968 Mexico final, but the pleasure there was definitely retrospective because the race was the toughest he ever ran.

12 Comments