Gerry Lindgren Profile

b. 9 March 1946

|

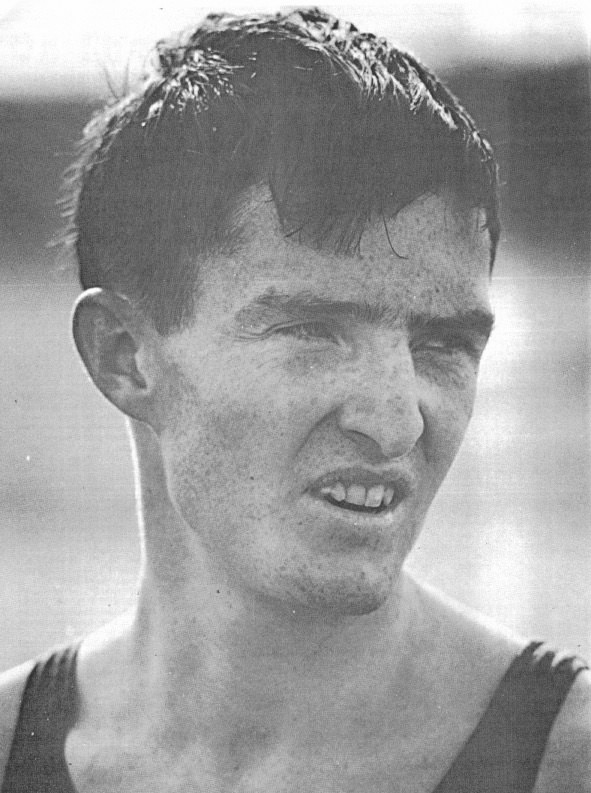

Few runners have appeared on the distance-running scene as dramatically as American Gerry Lindgren. In 1964 while still a schoolboy, he emerged from a remote area of Washington State near the Canadian border to run a series of world-class races. His successes that year took him to the Tokyo Olympics as one of the favorites in the 10,000.

Until the 1960s teenagers rarely competed in distance events. It was universally believed that distance running was a mature man’s sport; teenagers were strongly discouraged from running long distances on the road and track. Only in cross-country races were they allowed to run longer distances up to 5,000. Thus up to 1960 no American teenagers, except for Louis Zamperini, posted world class times in distance events. (In 1964 the top distance runners were in their late 20s: Jazy 28, Roelants 27, Clarke 28). Gerry Lindgren was the second teenage sensation in the 1960s. A 17-year-old Canadian, Bruce Kidd, had emerged from obscurity in the 1961 American indoor season as a world-class distance runner. Following Lindgren came Jim Ryun, Mary Decker, Steve Ovett and Dave Bedford. It is hard to find a clear reason for this emergence of teenage distance stars, but surely the youth-oriented 1960s culture (the Beatles, self-expression, Woodstock) must have been behind it.

But in Lindgren’s case, it was primarily his personality that led to his dramatic entry into world-class distance running. All distance runners can be called driven, but very few can be described as driven as Gerry Lindgren. Much has been written about the childhood abuse by a violent alcoholic father. This obviously had a strong effect on his personality, as did the stigma of his short stature and scrawny body. Hence, at the early age of 14, after he had finally found something he could possibly excel in, Lindgren began to train for distance running in a way that can only be called manic. He had something to prove.

Lindgren himself has done a lot to build up the story of his career. When describing his early running career, he claimed he was “totally uncoordinated” (Metzler) and devoid of any athletic talent. As well, he has offered many extreme claims over the amount of training he did as a teenager. A few years later, when Ron Clarke tried to calculate Lindgren’s mileage in his high school years, he was told that it amounted to 40 miles a day. Clarke wouldn’t believe Lindgren’s claims and wrote 25-35 miles a day. “That fellow is either a physical marvel or the greatest con artist in history,” he said of Lindgren. (Gwilym S. Brown, “A Joyous Night for a Pixie” (Sports Illustrated, Feb. 26, 1967) Suffice it to say that the young Lindgren did show co-ordination as a runner and that he trained unusually hard as a student at John Rogers High School in Spokane under the supervision of Coach Tracy Walters.

---

Early Impact

After an initial two years of hard training (1961-1962), Lindgren broke a bone in his foot and missed the 1963 season. It was following this year out that he made his first step into top-class competition. On December 27, 1963, the 17-year-old won an indoor Two Miles in San Francisco in 9:00 flat. This improved his PB from 9:24. Three weeks later, on January 18, he ran another Two Miles in Los Angeles against Gaston Roelants, who a few months later was to become the Olympic Steeplechase champion. The Belgian won in 8:41.2, but Lindgren was not far behind in 8:46.0, a schoolboy record.

|

|

Lindgren soon competed against the world's best distance runner, Ron Clarke. |

This was another amazing breakthrough, but there was a cost for this success. He was getting sick with colds and sore throats and was having to take penicillin. His ambitious training regime was already taking its toll. Despite his health, there was another breakthrough to come. A week later in another 2 Miles he ran a fine second to distance great Ron Clarke, dropping his PB another six seconds to 8:40.0. Track Newsletter was impressed: “So sensational is his 8:40 that it is 4.6 seconds faster than any US citizen ran the event outdoors last year.” (Feb. 19, 1964) Then at the AAU indoor 3 Miles he ran a remarkable third behind Clarke (13:18.4 indoor WR) and McCardle to complete his indoor season with a 13:37.8 clocking.

His 1964 indoor season proved to be no flash in the pan; his outdoor races saw him maintain this new level of performance. All of a sudden was competing as an equal with America’s top distance runners, Bob Schul and Bill Dellinger. To do this, he required both physical and mental strength. In fact, one of his strengths was his mental approach. He was a superb competitor who was always running to win and was always putting himself on the line. Most journalists, distracted by his eccentricities, did not perceive the teenager’s intelligence.

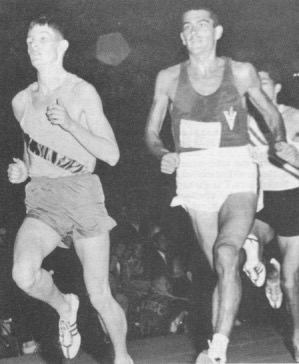

Challenging America’s Best

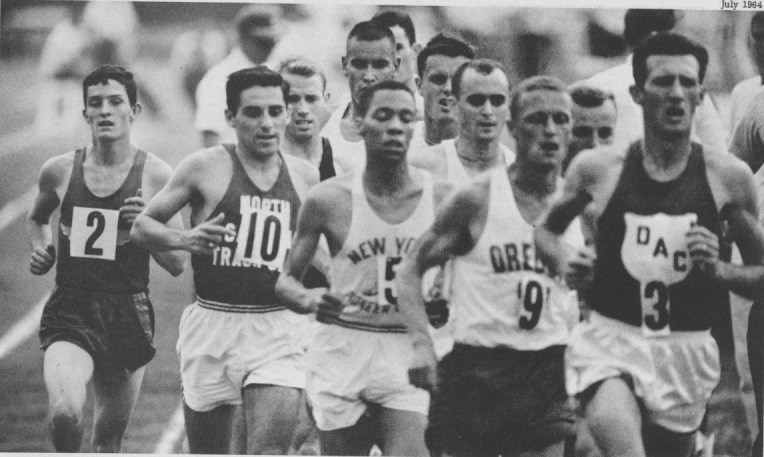

|

| Battling with Dellinger (rt.) and Schul. |

After a series of low-key outdoor races in April and May that included a schoolboy-record 4:06.0 Mile, Lindgren began a series of top-level races with the USTFF 10,000 in early June. He showed his strength by winning from 34-year-old John Macy in 29:37.6. Two days later he lined up for the 5,000 at the Compton Invitational, facing Kiwi Bill Baillie, Bob Schul and Ron Larrieu. Undaunted, Lindgren was in the thick of things from the start; in fact Bert Nelson reported that “it was Lindgren who was responsible both for the fast time and most of the excitement.” (Track Newsletter 10:21, p. 161)

Lindgren was in first or second for the first mile (4:20.9) and the second mile (8:53. 6). When the big guns took over he was able to stay with them until 11 laps (12:15). Back in fourth he lost ground in the last 600, passing 3 Miles in 13:18 and hanging on for a stunning 13:44.0 PB. He had broken Beatty’s 5,000 American record by one second but so had Schul and Larrieu: 1. Schul 13:38.0; 2. Baillie 13:40.0; 3. Larrieu 13:43.0. Schul was only three seconds outside Kuts’ world record. All of a sudden the 18-year-old was tantalizingly close to WR standard; his 13:44.0 would rank him seventh in the world for 1964. This American high-school record of 13:44.0 stood for 40 years until Galen Rupp surpassed it.

Could Lindgren maintain this kind of form through to October when the Olympics would be held in Tokyo? His next test was in the Olympic pre-trials where he faced Schul, Beatty and Dellinger over 5,000. Again he did most of the leading and it was only in the last lap that he was left back in third: 1. Schul 14:10.8; 2. Dellinger 14:11.4; 3. Lindgren 14:13.8. The two older athletes were too fast for him on the last lap, but he again showed competitiveness and consistency.

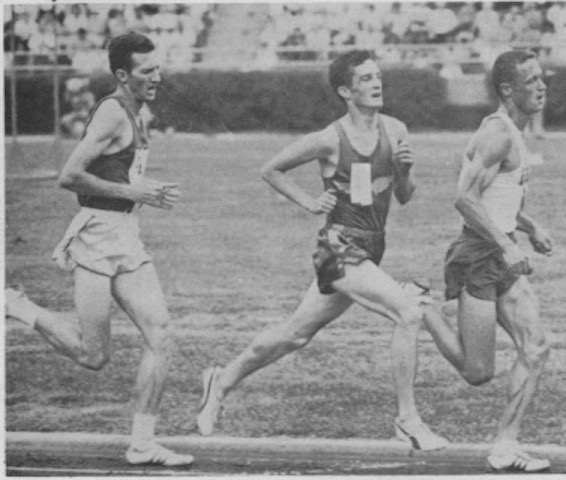

First International Race

|

|

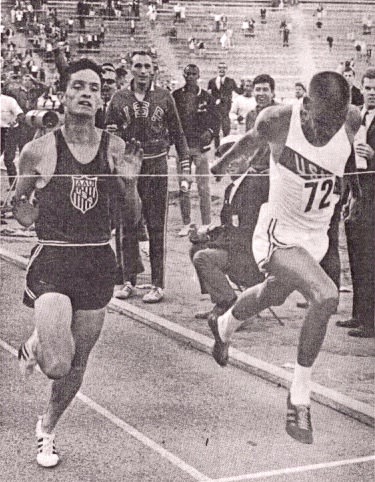

USA v USSR 10,000: Hanging on to Dutov and Ivanov. |

Lindgren became the centre of attention when he was selected to represent his country in the July USA v USSR match. The best Russian distance runners were considered unbeatable over 10,000, and many considered the raw talent of Lindgren as no match for them. But from the selectors’ point of view, Lindgren had never shown respect for any name runners and could therefore be expected to give the Russians a good race. His coach Tracy Walters thought Lindgren was ready, having had him training three times a day. Just before the meet Walters had his runner do two three-mile runs with a five-minute jog between. He ran 13:58 and 13:30. “I was astounded,” the coach said. (Track Newsletter 11:1, p. 1) But Lindgren’s two upcoming Russian competitors, Ivanov (28:48.6) and Dutov, had run more than 25 seconds faster than his only 10,000 time of 29.37.6.

|

|

A landmark in American distance running. The Russians are finally beaten. Note the crowd. |

In 93-degree heat, Lindgren started sensibly, letting the Russians dictate the pace. Alternating leads, Dutov and Ivanov set an ambitious pace, clearly planning to burn off the two Americans. For over half the race, the 18-year-old sat comfortably in third as the Russians passed miles in 4:37, 9:21.7 and 14:07.3. On the 16th lap, when Ivanov moved 20m ahead of Dutov, Lindgren was urged to move up by American coach Sam Bell. His response was dramatic. He put in a 63 lap (some say it was 60) to pass both Dutov and Ivanov and establish a lead of 7m. It was a dramatic move, but it left Lindgren in trouble: “I even looked back once to see if I was losing it. And I’ve never done that before.” (John Underwood, “Raves for the Young,” Sports Illustrated, Aug. 3, 1964.)

Buoyed by the cheers of the 50,519 crowd, Lindgren held on to run the next lap in 68, increasing his lead over a surprised Ivanov to 15m. He passed 4 miles in 18:52.2, for a 4:45 fourth mile. Thereafter he gradually increased his lead. A last lap of 63 saw him with a 150m lead at the tape. Many years later Lindgren explained why he was able to be the first American to beat the Russians over 10,000: “ I was racing hard and they were running logically… When I suddenly ran a fast lap, they didn’t know what to do because that wasn’t logical…. You can’t be that logical. Running is a sport of passion; it’s not a sport of logic.” (Brian Metzler interview, March 11, 2011, Internet.) 1. Lindgren 29:17.6; 2. Ivanov 29:39.8; 3. Dutov 30:51.8.

Tokyo Olympics

So far Gerry Lindgren’s career seemed close to perfect. Now in his eighth month of continuing competition, he was still able to maintain peak form as the Olympic trials approached. After opting out of a Swedish tour, he kept sharp by running two races in Jamaica. First he ran a fast PB Mile in 4:01.5 (3rd) and then broke the American 3-Mile record with a PB 13:17.0 (1st). This would not go in the record books, however, as Schul had recently run faster.

|

|

Lindgren moves up on a star-studded field: Bob Schul (3),Bill Dellinger (9), Lou Scott (5) and Jim Beatty (10). |

On September 12, he qualified for the Tokyo Olympics with a convincing 10,000 victory in the US trials. He ran with Billy Mills for 23 laps and then moved ahead to record an 8.4 second victory in 29:02.0. This was the second fastest time ever recorded by an American and was 15.6 seconds faster than his win against the USSR. He then withdrew from the 5,000 trials. Everything looked fine as he arrived in Tokyo as one of the favorites for the longest track race. But then came a setback that put an end to what would have been a fairytale ending. He rolled his ankle in a hole while out on a pre-race run. Unable to get treatment for several hours, he didn’t fully recover for his Olympic race.

Even without the ankle injury, Lindgren would have been hard-pressed as 14 of the competitors had, unlike him, broken 29:00 for 10,000. He was also suffering from an infection. After staying with the leaders in the early stages, he began losing contact in the fifth kilometer and finished ninth in 29:20.6, a performance still to be proud of. He told Gary Cohen, “Before the race the German doctor had taped my leg to isolate the injury and I was able to run, but the tape was hurting so badly that I removed it before the race. In the beginning I took off with everybody, and it was an easy pace. I was running up in the front with Clarke, Mills and Gammoudi and everyone else. After about 3,000 meters I thought…that I couldn’t just sit and wait. I took off into the lead and ran my race. I sprinted but the pain went up my leg and into my back and I was through. Many runners went by me and it was terribly disappointing.” (garycohenrunning.com)

Thus ended a fairytale season that had stretched from January to October. Had someone foretold at the start of 1964 that Lindgren would place 9th in the Olympic 10,000 final, few would have believed it. This performance was nevertheless anticlimactic, especially since in the Olympic trials he had easily beaten Billy Mills, the man who won the Olympic 10,000 gold medal ahead of him.

University

Back home in Pullman, there were big changes in his life. He became a university student and acquired a new coach, Jack Mooberry, who wisely gave him a fairly free rein. And since NCAA rules prevented freshmen from college competition, Lindgren was free to compete as he wished at the senior level in 1965. Indoors, after a couple of Two-Mile losses to George Young (8:55.1 with a cold and 8:47.2), he rounded into form at the end of January with two fast wins in 8:37.9 ( 2.1 seconds faster than his 1964 PB) and 8:40.9.

Outdoors he began with a comfortable Two-Mile win at the Coliseum Relays (8:39.0). On June 11 he ran a fast 28:21.8 Six Miles at Bakersfield; this was a collegiate record, and he won by 2:04 minutes. Passing 3 miles in 13:54.6, it looked like he was going to go under 28:00, but he developed a stitch. Still it was a good sign that he was in top form for the AAU nationals two weeks ahead.

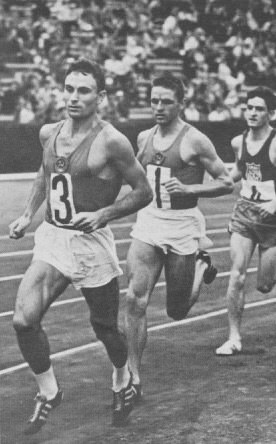

Battle with Mills

In fact, he was in world-record form. Together with Billy Mills, the 10,000 Olympic champion, he set a new WR for Six Miles. Working together, these two fiercely competitive runners took turns leading throughout the 24 laps and then raced neck and neck over the final 120 yards. Mills took it out with a 4:29 mile before Lindgren took over. Exchanging the lead several times, they covered the next two miles in 4:34 and 4:36 to reach the halfway in 13:39.8—27:20 pace. This meant that Lindgren and Mills were perfectly paced to break the current Six Miles WR of 27:17.6.

|

|

Mills outleans Lindgren, but both clock 27:11.6. |

They slowed to 69s in the next mile (4:36.5), but then Lindgren threw in a 67.5 and the fifth mile was covered in 4:33.6. They needed a 4:27.9 final mile or four 67 laps to break the world record. Mills led for the next two laps in 68.4 and 69.2, leaving them needing to run the last 880 in 2:10.3. After a 66.1 penultimate lap, all they needed was a 64.2. The 25,000 spectators roared them on as Mills led down the back straight. Lindgren moved up beside Mills as they entered the last bend. For the last 120 yards they ran side-by-side, with Mills just leaning at the tape to win. The 19-year-old and the 26-year-old received the same time, a world-record mark of 27:11.6 that cut 6.2 seconds of Ron Clarke’s 1963 mark. The two had covered the last lap in 58 seconds. The time compared favorably to Clarke’s 10,000 record of 28:14. (Later in the summer Clarke shattered both records with 26:47.0 and 27:39.4)

European Tour

Two days (40 hours) later, as the new WR holder, Lindgren was across the Atlantic in Zurich racing Briton Derek Graham and Olympic Steeplechase champion Gaston Roelants over 5,000. Showing amazing recuperative powers, he was leading at the bell, when both runners came by. Still not giving up, Lindgren hung on and managed to pass Roelants in the final straight. 1. Graham 13:51.6; 2. Lindgren 13:52.0. A week later he ran second (7:58.0) to Harald Norpoth (7:55.2) over 3,000.

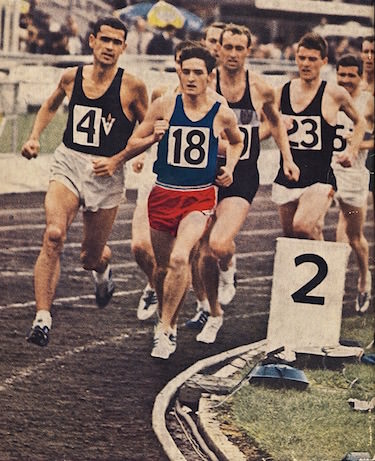

|

|

Lindgren leads Clarke (4) at the start of the White City 3. |

Next it was on to London’s White City to race Clarke and Mecser over Three Miles. It proved to be one of the greatest races of all time as Clarke obliterated his own WR by 8.0 seconds with 12:52.4. Gerry North took the first lap in a fast 62 seconds, and then Lindgren went ahead to pass 880 in 2:07.2. But this wasn’t fast enough for Clarke, who took over on the third lap. After another fast lap (63.8) Lindgren again went to the front and passed one mile in 4:15.4. Not surprisingly, the rest of the field had already lost contact. Clarke later wrote, “The pace worried me. I felt pretty awful, but what could I do when such a terrier as Gerry was on my heels?” (The Unforgiving Minute, p. 146)

Clarke led for the next mile with steady 65-second laps, although he did surge a couple of times, no doubt testing Lindgren. With two miles covered in 8:36.4, which was faster than Lindgren had ever run, a world record and a sub-13:00 looked likely. And the White City crowd was going crazy. After a 66.4 ninth lap (the slowest of the race), Lindgren had the audacity to challenge for the lead. Clarke decided to surge again: “I put in my fastest surge yet,” Clarke wrote. “This one really hurt…. Gradually I realised that Gerry was dropping off. Instead of being on my shoulder, he was three or four yards behind.” (p.146) Clarke’s tenth lap was a fast 64. With Lindgren now falling back, Clarke turned his attention to the clock and powered on with a 4:16 last lap for a world-record 12:52.4. Meanwhile Lindgren grimly held on with a 4:27.6 last mile to record 13:02.4.

Afterwards, Clarke admitted to being scared of Lindgren. Lindgren’s performance was a great one, the third fastest all-time for Three Miles, but it was somewhat overlooked in all the excitement over Clarke’s run. Nevertheless, Clarke himself fully appreciated Lindgren’s run: “Pressed into running a lap of honour, I could only think of how much I owed Gerry and asked him to accompany me.” (p.147)

Lindgren went down with a cold after his White City race and withdrew from a Paris meet. He did however run a Three Miles on July 21, coming third (13:26) behind Graham and Wilkinson. He was still suffering from a cold at the end of the month when he was in Kiev for a return match against the Russians. This time Ivanov and Dutov won convincingly ahead of a sick Lindgren, who struggled with a 29:00.8 for third.

Lindgren still had two more international obligations in Europe. First he ran for his country in Warsaw over 5,000, defeating Lech Bogusewicz 13:43.4 to 13:46.6. Four days later faced the German Norpoth over the same distance, this time losing 13:47.8 to 13:50.4. His long 1965 season was over. It had not been as meteoric as his 1964 season—how could it have been?—but it had produced some excellent times if not many wins. In the world rankings he was 3rd in the Three Miles, 21st in the 5,000, 2nd equal in the Six miles and 20th in the 10,000. As well, he had run a world record (Six Miles) and an American record (Three Miles). On the negative side, he again showed himself susceptible to colds, an indication that his immune system couldn’t cope with the workload of training and competing.

1966

The next year saw him with another chronic health problem, this time in his stomach. Nevertheless, he managed to compete well both as an individual in AAU meets and as a freshman in collegiate races. To start, he lost five of his six AAU indoor races. His first race earned him a good second-place 8:34 PB for Two Miles, but his other times ranged from 8:39.2 to 8:48.2. Then came the NCAA indoor Two Miles. Despite “stomach flu,” he gained his first NCAA title with an 8:41.4 win over John Lawson. Using his usual catch-me-if-you-can tactic, he roared off with a 61.5 first lap and soon was out on his own with John Lawson. Lawson managed to stay close, but Lindgren had no trouble holding him off with a 1.8-second margin.

Two months later on May 14, he stunned the running world again, this time with a 12:53 Three Miles. This early-season performance in the PAC Northern Division meet in Seattle was a complete surprise. On a cold and windy day, Lindgren came within 0.6 of a second of Clarke’s highly respected world mark, which coincidentally was set in the 1964 White City race where Lindgren finished second. This breakthrough, improving his 3-Mile time by eleven seconds, came about just as critics were wondering whether Lindgren’s indoor form showed he had reached his limits.

After the race, Lindgren claimed that he wasn’t thinking about records and that it was only after he heard the two-mile time that he thought the WR was possible. He went through the first two miles in 4:14 and 8:37, times almost identical to those in his White City race with Clarke. He then ran the next three laps all in 66 and finished off with a 58.

Following this amazing run—he was only the second person to run 3 Miles under 13:00--Lindgren was clearly on a roll. He continued with a 13:12.8 Three-Miles win at UCLA. Next, he equaled the American 5,000 record in the Compton Invitational. In this race, he was clearly in a class of his own despite the presence of Tracy Smith and Ron Larrieu. He ran 4:16, 8:43.4, and 13:11.2 for the first three miles. His finishing time of 13:38.0 put him 7.6 seconds ahead of Smith and 18.2 seconds ahead of Larrieu. Still apparently unstoppable, he next achieved a double at the NCAA championships with 28:07.0 for Six Miles and 13:33.8 for Three Miles. His comfortable winning margins were 9.6 and 13.2 seconds.

After this fine double, his health broke down again; viral bronchitis kept him out of the AAU championships. In fact, he spent a week in hospital. And his 1966 track season was over.

Bouncing Back in 1967

Almost five months later, Lindgren was back in shape, winning the 1966 NCAA cross-country race from Tracy Smith by ten seconds. And once on the boards in early 1967 he showed general improvement in his Two-Mile times, beating Bill Baillie in Seattle with a PB 8:31.6 and then beating Ron Clarke (recovering from flu) in 8:32.6. Finally he netted yet another NCAA title, winning the 2 Miles (8:34.7). The three wins showed him running indoors at a higher level than before, but physically he was still suffering.

Over a series of low-key meets for WSU in the spring, he was again dealing with stomach problems. He ran mainly over a Mile, once running a good 4:02.4 in Seattle. After a couple of 3 Miles in May (13:34.6, 13:37.6), he was in good shape for the mid-June NCAAs, this year at altitude in Provo, Utah. As in 1966, there was no real competition for an in-form Lindgren; he repeated his double winning the 6 Miles in 28:44.0 with a 13.4–second margin and the 3 Miles in 13:47.8 with an 11-second margin. His six-mile time was impressive in view of both the altitude (4,500 ft) and the lack of competition.

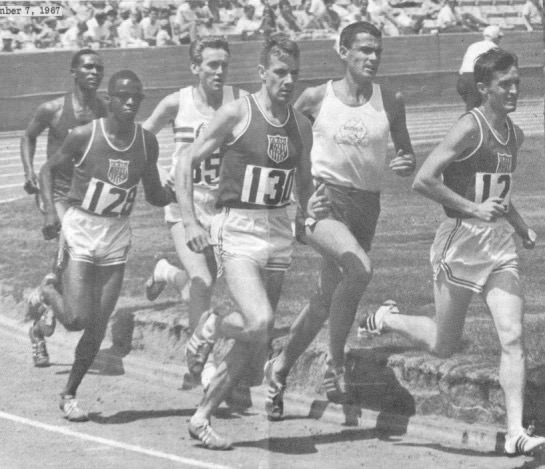

|

|

USA v Commonwealth. Lindgren leads Ron Clarke, Bob Day, Dick Taylor,Lou Scott and Kip Keino |

But his stomach was still troubling him, and he had to dig deep to win the AAU 3 Miles (13:10.6). He began in his usual assertive manner, reeling off laps of 64, 63 and 65. Only Bob Day was with him when he passed the Mile in 4:18.4 with almost a 20-yard lead on the field. Then stomach pain slowed him, and Lou Scott moved up, eventually taking the lead at 2 Miles (8:51). Two laps later Lindgren dropped off Scott’s pace and at one point was five yards back. Then he managed to pull Scott back in the penultimate lap. At the bell, he sprinted away from Scott and had a 20-yard lead with 200 to go. Lindgren held on for a 10-yard margin at the tape.

Lindgren had the same stomach problem two weeks later in the USA v Commonwealth meet in Los Angeles. After leading a prestigious field for 10 laps, he had no answer to a surge by Kenyan Kip Keino. Ron Clarke and Dick Taylor went past too, but Lindgren courageously held on and managed to pass Taylor in the last lap to earn points for the USA. 1. Keino 13:36.8; 2. Clarke 13:40.0; 3. Lindgren 13:47.8. That was the end of his 1967 season; he didn’t tour Europe with the USA team for the three international matches. Clearly he was in no condition to race competitively.

More Recuperation

A clear pattern was developing. As in 1966, Lindgren exited the track season a sick man; as in 1966 he reappeared as the winner of the NCAA cross-country race in November. This time the race was held in frigid temperatures in Laramie, Wyoming. Clad in long underpants and gloves, he overcame the field, the 7,300 ft altitude, the wind and the 25f temperature, to record a clear 15-second victory. But was he back to full health and ready for another Olympic year?

Sadly the answer was no. Apart from some good form in May and June when he beat Bob Schul’s 5,000 American record, Lindgren disappointed in 1968. He started with a rare NCAA-championship loss when Jim Ryun outran him in the indoor 2 Miles, 8:38.9 to 8:40.7. Then, after a 30-yard 2-Mile loss to Arne Kvalheim in Eugene, he ran his best race of the year in a 5,000 at Modesto. Racing against his idol Ron Clarke, he triumphed in 13:33.8, an American record over four seconds faster than the mark he shared with Bob Schul.

This race has to be one of Lindgren’s greatest; it showed what he was capable of when in good health. In what was really a two-man race, Lindgren led from the start, passing the first mile in 4:17.2 and the second in 8:46.2. The pace slowed to a 68.8, prompting Clarke to take over. He unleashed at 63.2, which left Lindgren trailing by four yards. But a slower 66 lap enabled Lindgren to re-establish contact with the Australian. Sensing a weakness in his opponent, Lindgren went ahead and ran a 63 lap that gave him a 10 yards advantage at 3 miles (13:07). He was able to maintain his drive to the finish, completing the last 1320 in 3:11.2. The margin of victory was 2.0 seconds at the tape. He never ran faster over 5,000.

This good form, which augured well for the upcoming Mexico Olympics, helped him overcome “continual stomach problems, bad tendons and raw blisters” (T&FN, June 1968), to achieve his third consecutive NCAA double over 5,000 and 10,000 with 13:57.2 and 29:41.0. He won the 10,000 easily by 15.8 seconds , but the 5,000 was a different matter. “I had strained my achilles winning the 10,000 and could hardly walk the next day. So when the 5,000 came around, I knew I was in trouble. I led the race through the first mile, but my achilles got so bad that I couldn’t hold the pace.” (Metzler) At the bell he was in seventh, but he dug deep and made a last-ditch effort. A 58 last lap took him past all the six runners ahead of him. His time was 13:47.2.

Olympic Trials

After skipping the AAU, he made a short trip to Europe despite ongoing achilles problems. First he thrilled a German crowd with a spirited victory over Jürgen May in Stuttgart. He never gave up after May had stormed past on the back straight of the final lap. He held on round the bend and then overtook May in the final run-in. He ran a 57.5 last lap. But in London two weeks later he trailed in a distant third behind Dick Taylor. He led the first mile in 4:17 but then slowed. Taylor made his move with 62.8 and 61.6 laps and the race was over. The Brit was 47.8 seconds ahead at the end. Lindgren’s time was a very slow 14:16.8.

Back home Lindgren needed to qualify for the Mexico Olympics. He began with a “pre-trial” 5,000 that saw him back in 4th place 14.8 seconds behind winner Bob Day. Six days later, with his leg taped for his achilles problem, he had a big battle with Kenny Moore over 10,000. After doing all the leading, he was passed by Moore near the bell and was unable to get back on even terms: 1. Moore 28:55.0; 2. Lindgren 28:55.2.

Desperate Times

Despite his achilles problem, Lindgren was planning to run both races in the Olympic trials. The 10,000 came first. It looked hopeful as he stayed with the leading group while one by one runners dropped back. But at 8,000, with only five runners still in the hunt, he began to drop back himself. He finished fifth in 30:44.2, 34.4 seconds away from an Olympic berth.

The 5,000 trial witnessed yet another remarkable effort by Lindgren. He fell back from the lead group after seven laps. But he didn’t give up even when he was 30m out of an Olympic qualifying position. On the back straight of the last lap he had 10m to make up on third-placing Lou Scott. He caught Scott at the end of the last bend, but the effort was too much, and Scott was able to respond and hold him off by 0.4 of a second. This was heartbreaking after such a great effort, although a cold assessment would say that Lindgren would still have been hobbling had he gone to Mexico. In fact he didn’t race again until the following May—a longer recuperation break than usual.

Wind Down

Gerry Lindgren competed for five more seasons from the age of 23 to 27. His competition was generally outdoors and in the USA. Although unable to recapture the form of earlier years, he still dreamed of an Olympic success and continued to train hard. In early in 1972, as he prepared for the Munich Olympics, he claimed he was running 50 miles a day.

|

|

Lindgren was unbeaten in his four NCAA cross-country championships. |

There were a some highlights in the last five years of his career. His most successful year was 1969. He ran 8:35.4 for 2 Miles (2nd to Bacheler) and 13:18.4 for second place in the AAU 3 Miles behind Tracy Smith. His best race of the year was a 5,000 win (13:38.4) in Stuttgart, where he was representing the Western Hemisphere against Europe. In November he ran his last NCAA cross-country (he had redshirted in 1968), winning the title again by two seconds from Mike Ryan and Steve Prefontaine and completing a series of four successive wins.

He was less successful in 1970, placing 3rd in the AAU 3 Miles (13:25.0) and 5th in the AAU 6 Miles (28:05.8). In the 3 Miles he was in the race to the end, finishing less than a second behind Shorter and Riley after a 57 last lap. He had no major wins in 1971, although he ran respectable times in placing 4th in both the AAU 3 Miles (13:04.4) and Six Miles (27:46.4). His last attempt at Olympic glory was a sad failure. He dropped out of the 10,000 trial and was last in the 5,000 trial. His amateur career was over at age 26.

Following his last attempt to make the Olympics in 1972, he had to enlist for military service. Suffering from a stomach ulcer, he was out of the army after 47 miserable days. Near the end of the year, he joined the emerging pro circuit, committing to compete in 36 of the scheduled 50 races in 1973. He ran a few 2 Mile races in the spring of 1973, finishing behind either Keino or George Young. Although he was able to break 9:00, he was clearly not fit enough to continue. He called his 1973 spring, “as miserable a season as I had had.” (Rick Riley, Gerry Lindgren?” Track & Field News, February 1975). At the end of May 1973, he ceased competing.

Conclusion

Gerry Lindgren was one of the most colorful personalities in the history of American track. Although he undoubtedly had his flaws, he had the strength of character to break new ground both in training and racing. At a very young age, with the help of his high school coach Tracy Walters, he undertook a training program that was more ambitious than any before it: “We knew that Emil Zatopek ran to the point of exhaustion and beyond,” he told Arthur Daley. “We knew that Herb Elliott ran through sand dunes and that Peter Snell ran up and down hills. We sort of combined them all into what was best for me.” (New York Times, 13 Oct 1964) It took an incredibly strong will to carry out the resulting program. A sense of his attitude toward training can be gained from an article by Ruth Seabrook: “He said the body would fight you for weeks, then finally it would relent and allow you to do the impossible. His self-belief and disregard for the boundaries of his own physicality were inspiring.” (“The Spokane Sparrow,” Internet)

As for racing, he always competed with passion and never feared any competitor, not even his idol Ron Clarke. He almost always went to the front and tried to run the opposition into the ground, either by sheer pace of by bursts of speed. “To die at the end and lose is a little disappointing,” he told Brian Metzler, “but it’s better that holding back and not even being there. Instead of going out there trying to win the race, you go out hard and you’re trying to make sure that whoever wins the race has just run the first mile as fast as he’s ever run a first mile before. Then you’ve got a chance because you’re tired and everybody else is tired too.” (Brian Metzler, Interview March 11, 2011)

Many journalists have commented on his physical appearance. Kenny Moore’s description is helpful: “His person was an affront to bedrock beliefs. Runners were lean and corded. Runners took years to develop. Yet here he was, a child, without a visible muscle. Moreover, what I had just seen him do had to have made him suffer. But he didn’t look it. The gulf between his appearance and performance was so immense that it seemed something outside of nature had happened, something surreal and disturbing.” (Kenny Moore, “A Life on the Run,” May 18, 1987) Moore, unlike many other journalists, also noted Lindgren’s intelligence: “He was clearly bright.” Tracy Walters was also impressed by Lindgren’s thinking: “This fellow is so much more astute, has so much more depth than you can imagine.” (Gwilym S. Brown, Sports Illustrated, Feb. 26, 1967).

Ultimately, Gerry Lindgren’s career as a whole was unfulfilled. Though there were many brilliant races, he leaves the impression that he could have done even better. He never improved on his 27:11 Six Miles, which he ran when just 19 in the second year of his career. And his best 3 Miles time was achieved just a year later, still early in his career. Further, he couldn’t qualify for either the Mexico or Munich Olympics.

There was one main reason for all this—his health. He paid the price for pushing himself so hard in training. It can be argued that all his illnesses and injuries originated from a weak physique and system. But if he had moderated his training, would he have reached the competitive level he enjoyed for a few years.

---end

7 Comments