1948 Olympic GamesLondon, EnglandJuly 29-August 14With Great Britain still recovering from WW2, there was much opposition against holding the 1948 Olympic Games in London. Britons were still subject to severe rationing and economic hardship. Thus expensive preparation for the sake of mainly foreign athletes was seen as a lesser priority. However, teams from abroad brought their own food and gave the surplus to hospitals. And frugal utilization of existing facilities lowered the costs. Psychologically, Britons needed a morale booster. And the Olympics definitely fitted the bill. Emil Zatopek had experienced the ravages of war in Czechoslovakia, and he clearly saw how badly needed the games were: "After all those dark days of the war, the bombing, the killing, the starvation, the revival of the Olympics was as if the sun had come out....I went into the Olympic Village and suddenly there were no more frontiers, no more barriers. Just the people meeting together. It was wonderfully warm. Men and women who had just lost five years of life, were back again." Despite the inability of the war-torn host nation to provide the best of facilities and accommodation, these Games produced large crowds and some fine competition. The White City stadium, where the athletics competition was held, saw crowds from 60,000 to 70,000 despite the often rainy weather.

PROFILE: ARNE ANDERSSON1917-2009b. Trollhätten, Sweden. 70kg/154lbs 5’10”/1.78 It was a great honour for the 21-year-old Arne Andersson to represent Sweden in the 1939 Finnmark competition against Finland. For his international debut, he had been chosen as the second string to Åke Jansson in the 1,500 after improving his 1938 PB by five seconds with 3:53.8. His role in the four-man race was to help Jansson win by pacing him until the final stages. Jansson, with a 3:52.4 PB, was expected to need help as his two Finnish adversaries, Hartikka and Sarkama, were also 3:52 runners.

Arne Andersson v Gunder Hägg (1944)1,500 Gothenburg, Sweden, July 7, 1944Great Races #4 In his first race of 1944, Gunder Hagg had been humiliated by Arne Andersson in a 1,500 race. Andersson had stayed with Hagg throughout and then roared by in the last 120 to open up a nine-meter lead. Hagg’s defeat had been so decisive that rumours spread that the great man had thrown the race.Clearly Gunder Hagg had to recapture his reputation as the world’s greatest runner. His plan was simple. In view of the devastating finishing kick that Andersson had demonstrated, a kick that seemed to be more potent than ever, Hagg would literally have to run his opponent off his feet with a blistering pace. To help with this plan, Hagg enlisted the help of 23-year-old Lennart Strand, who was to win a gold medal in the 1946 European Championships and a silver in the 1948 OG—both in the 1,500.

Gunder Hagg v. Arne AnderssonOne MileMalmo, Sweden, July 18, 1944A capacity crowd paid to see yet another great race between Arne Andersson and Gunder Hagg. The two Swedish runners had been rivals since 1942 and had had many exciting duels, often setting WRs in the process. Hagg had beaten Andersson every time in 1942, but this year, Andersson appeared to be Hagg’s equal. Not only had he beaten Hagg’s WRs for 1,500 and the Mile in 1943, but he had also beaten Hagg in their first 1944 encounter over 1,500. Then Hagg had won the second race. Clearly this third encounter of the season was going to be a classic.

With his talents, American miler Bill Bonthron could have conquered the world. He had strength, speed and a tenacious competitive drive. But while he performed brilliantly in his own country and even set a world record for 1,500 in 1934, he made little impact on the international scene and never competed in an Olympic Games. Following the traditional amateur conventions of his time, Bonthron planned his athletic career for just the four years of his university education. Once he graduated and married, his priority was his job as an accountant and he announced his retirement from running in 1934. Although he later broke with convention and continued to train seriously in his spare time, he never regained the form of his university years and failed to qualify for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He did make one European tour in his graduating year, but failed to live up to the reputation that had crossed the Atlantic before his arrival.

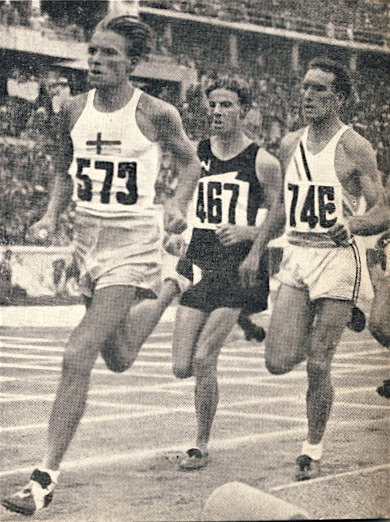

Gaston Reiff v Emil Zatopek 1948 Olympic 5,000 FinalGreat Races #6After his surprising win over WR holder Heino in the 10,000, Emil Zatopek lined up for the 5,000 as the crowd favorite. But there were two concerns about his chances: first, whether he had recovered from the earlier race, especially since he had put in a needless sprint at the end; and second whether his pointless race with Sweden’s Ahlden for first place in the 5,000 heats would take the edge off him. Others pointed out that the five-and-ten double hadn’t been achieved since Kolehmainen did “the impossible” 36 years earlier. Zatopek himself, after losing to Ahlden in the heats, thought that the Swede might just get the better of him in the final.

Glenn Cunningham Profile1909-1988 The life of 1930’s American miler Glen Cunningham has now become part of American folklore. It is the story of a young Kansas boy of pioneer farming stock who faced adversity with courage and determination to become a world-famous hero. This story, as it grew into folklore over many printed versions, has often been embellished with fictional details. However, the actual facts are powerful enough. When just seven years old, Glenn Cunningham was badly injured by a woodstove explosion that killed his brother. He spent over a year recuperating upstairs in his parent’s home before he was able to venture outdoors. His legs were so badly burned that it took him more than six months to stand, yet alone move. Yet through determination and self-discipline he learned to walk and then to run, eventually becoming a world-class runner.

The three favorites for this Olympic final were all reaching the climax of their careers. Luigi Beccali (29) of Italy had broken the WR for 1500 in 1933; he was also the reigning Olympic and European 1,500 champion. American Glenn Cunningham (25) was the current WR holder for the Mile, and he had been fourth in the 1932 Olympic 1,500 final. New Zealander Jack Lovelock (26) had set a Mile WR in 1933 but had not subsequently run as well. Still, a recent 3:01 time-trial over 1,200 showed he was back to his best form. These three great runners knew each other well from previous encounters on the track. Beccali had the best record, having beaten Cunningham once and Lovelock twice. Cunningham had beaten both men once, while Lovelock had beaten Cunningham three times. All three were known for great finishing kicks, so it promised to be a tactical race.

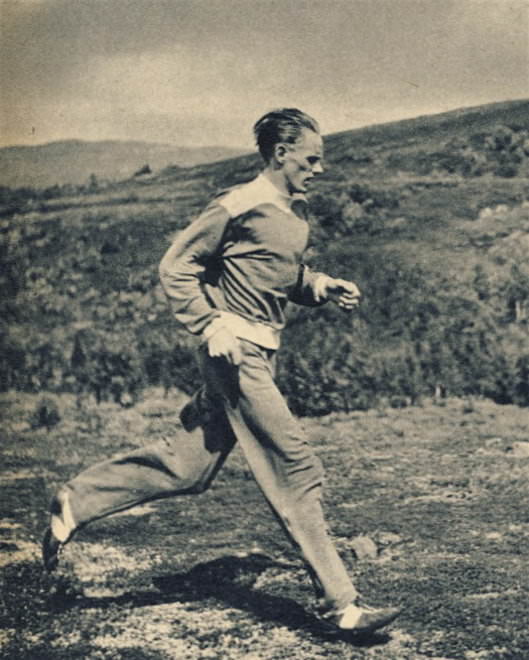

Gunder Hägg Profile 1918-2004 This great Swedish runner set fifteen WRs between 1941 and 1945. He improved the Mile WR by 5.0 seconds, the 1,500 WR by 4.8 seconds, the 3,000 WR by 7.8 seconds and the 5,000 WR by 10.6 seconds. As well as a record-breaker, Gunder Hägg was also a fierce competitor; his tactic of burning off all competition from the front worked almost perfectly until his penultimate competitive year (1944), when his great rival Arne Andersson beat him in five out of six races. Had not World War Two prevented Olympic and European Championships during his career, Hägg would surely have won several medals. After years of heavy physical work and then a consistent winter conditioning schedule of running and cross-country skiing, he developed into an almost perfect runner. A Times reporter noted “the smooth beauty of [his] stride which was mechanical only in the sense that perfect motion is mechanical.” (Aug.7, 1945)

Gunder Hagg’s Training (Much of the material for this article comes from Gunder Hägg's Dagbok, which was published in Stockholm by Tidens Förlag in 1952. I have also used an article, "Kanske Bättre Kondition än Någon Nånsin" written by Hagg for a handbook entitled Vålådalen published in 1953 by Åhlén and Åkerlunds Förlags AB.) Over a period of five years in the 1940s, while most of the world was at war, Gunder Hägg was rewriting the middle-distance record book in neutral Sweden. Many of these records were set in competition with his great rival Arne Andersson, and there is no doubt that this competition pushed Hägg to faster times. He was a great competitor who always came through in the big races. But fierce competition doesn’t fully explain his remarkable success on the cinder track. Also crucial were his early childhood conditioning and his innovative training methods.