OLYMPIC GAMES 1956

Melbourne, Australia, November 22-December 8

800

|

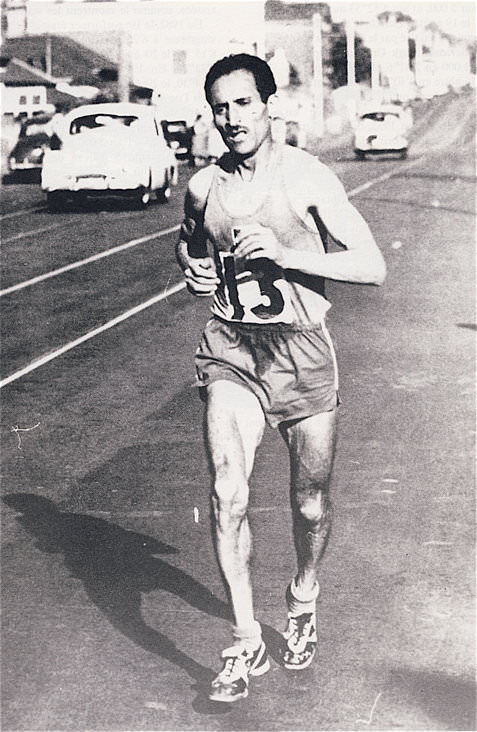

| Courtney (153) passes Johnson with a supreme effort. |

The finalists lined up in gusty conditions, while the last bend was still being compacted by two large rollers. Fortunately, the attention of the starters was alerted. After a delayed start, American Tom Courtney, who was the favorite for this event, went straight into the lead from compatriot Arnie Sowell and Britain’s Derek Johnson. On the back straight, Sowell took over and led Courtney and Johnson through 400 in 52.6. The two Americans stayed ahead in the next 200, while Boysen moved up to Johnson. On the crown of the last bend Courtney moved up beside Sowell, and the two Americans ran side by side into the final straight, with Johnson in hot pursuit. But then the Americans moved apart, allowing Johnson to sprint through between them. For “eight unbelievable strides,” as The Times correspondent put it (Nov. 27, 1956), Johnson was in the lead. But Courtney showed his amazing strength by responding and gaining a two-foot lead over Johnson at the tape. Boysen finished as fast as Johnson and was only 4/10 of a second behind Courtney for the bronze. A fading Sowell was fourth just 2/10 back.

1. Courtney USA 1:47.7; 2. Johnson GBR 1:47.8; 3. Boysen NOR 1:48.1; 4. Sowell USA 1:48.3; 5. Farrell GBR 1:49.2; 6. Spurrier USA 1:49.3.

1,500

The Melbourne stadium was packed with over 104,000 for this race. All Australian eyes were on the Mile WR holder, hometown favorite John Landy. Expectations of him were high, even though he had been struggling for months with an injury. He was hoping that his team mate Merv Lincoln would make the pace fast if he could. He also had been promised the support of the New Zealander Halberg.

|

| Delany outsprints the field for a clear win. Richtzenhain and Landy (156) take the other medals. |

Running in only his fourth 1,500, 23-year-old Murray Halberg led from the gun. He clocked 58.6 for the first lap. Merv Lincoln, Landy’s team-mate, who had needed a painkilling injection before the race, took the lead before 600 and passed 800 in 2:00. The third lap was where Landy usually made his move, but this time he was well back. Lincoln still led at the bell (2:46.8). At 1200, Hewson of Great Britain, who had been running beside Lincoln round the bend, made his move. “The rest of the field came after me like a pack of hounds in full cry,” Hewson wrote later. “The advantage I had expected to gain through my surprise move never materialized.” (Flying Feet, p.85) Nevertheless, he led till almost home straight from team-mate Boyd and Ritzenheim. Landy was moving up, dogged by Delany, but he wasn’t willing to run too wide on the bends. In the final straight, a lucky Delany found a gap to come through on the inside. He burst into the lead on the final straight as if from nowhere to win gold. His last lap was 53.4. Landy, clear at last, finished with a 54 lap that brought him from last to third behind Ritzenheim. “I thought I had no chance at all before the race,” Landy said after. “Only in the last straight did I begin to hope…. I lost confidence because I couldn’t train regularly [before the Games] and how I got up to win the bronze medal was a bit of a miracle.” (Keith Donald and Don Selth, Olympic Saga, p.107)

Roger Bannister, reporting on the games for Sports Illustrated, had an interesting view on this race. “To say that Delany was lucky to win does not detract from the brilliance of the young Irishman’s running. He succeeded in a crowded field in getting to the right position at the right time with enough energy left to make the most of it.” (SI, 7 Jan. 57) Bannister also talked perceptively of the pressure on the hometown favorite John Landy. “I believe Landy could have won this race. But he ran as though he knew he could not win; he ran for a place and not for a gold medal. Had he regained his confidence before the race and by chance or good planning held Delany’s position on the last bend, I think the story might have ended differently. (SI, 7 Jan. 57)

1. Delany IRE 3:41.2; 2. Richtzenhain GER 3:42.0; 3. Landy AUS 3:42.0; 4. Tabori HUN 3:42.4; 5. Hewson GBR 3:42.6; 6. Jungwirth CZE 3:42.6.

5,000

Vladimir Kuts no doubt had a psychological advantage after his crushing 10,000 victory five days earlier. But this time there were three English runners who were all strong contenders: Gordon Pirie, who was the 5,000 WR holder; Derek Ibbotson; and Chris Chataway. But there was no chance that class-conscious Pirie was going to work with his rival Chataway, an Oxford graduate. In fact, in a pre-race talk with Ibbotson, Pirie said that he regarded Chataway as his biggest threat. Ibbotson had wanted the three Brits to run as a team, but Pirie was never going to agree. All three Brits had better finishes than Kuts, so they would surely have benefitted from working together to keep in touch with the Russian.

Kuts went straight into lead with a 62.2 lap. At 1,000 ( 2:40.1) Pirie and Ibbotson were right behind Kuts, with Chataway seventh. Positions were unchanged to 2,000 (2:46.1 for 5: 26.2). By 3,000, which was reached in the fast time of 8:11.2 (2:45), all three Brits were grimly hanging on to Kuts, Chataway having moved up on the sixth lap. The fifth runner, Thomas of Australia, was 40m back. It was at this point that Chataway moved into second. He held on to Kuts for 600 but then lost contact. Kuts had escaped from the English trio.

After the race, Chataway explained that he had moved up to second in a desperate move as he was developing stomach cramp. Ibbotson, in his book, blames Pirie for the loss of contact: “Chataway was unable to go with him, and for three vital seconds Pirie dithered… [I] wished I had sensed the danger early and gone up. Instead, I had blind faith in Gordon. Until then the race had provided me with no difficulty.” (4-Minute Smiler, p,90) Pirie, in his book, had a different perspective: “I had to concentrate on Chataway and Ibbotson round the next bend. As we came into the home straight I was shocked to see Chataway had allowed Kuts to break away.” (Running Wild, pp.158-9)

|

| Pirie and Ibbotson (188) staying close to Kuts in the early stages. Albie Thomas is fourth. |

All of a sudden, Pirie and Ibbotson were 10m adrift, and Chataway was out of contention. The two Brits were unable to pull Kuts back as he sped up each time they got close. Kuts was through 4,000 in 10:57.4 (2:46.2), ten yards ahead of Ibbotson and Pirie. Laps of 66.8 and 64.8 enabled Kuts to increase his lead to 50m by the bell. Even though Pirie and Ibbotson sprinted hard for second place, Kuts increased his lead to 60m by the tape. His last was 62.2, and his last K 2:42.2. His time was a brilliant 13:39.6. Only Pirie had ever run faster. Pirie (13:50.6) easily outsprinted Ibbotson, who ran a PB of 13:54.4. Behind them Szabo came fourth, some 50m back. In 11th place was Chataway, who despite his stomach ailment had struggled on. “I really thought I had a chance,” he said in an interview many years later. “But after seven or eight laps when all was going well,, I was absolutely paralysed with stomach cramp. When it hit I slowed immediately. It was automatic.” (Track Stats 43:3 (Aug. 2005)

For Kuts, this second gold established him as the number-one distance runner. Iharos might have run more WRs, but Kuts, who was the reigning European 5,000 Champion as well, could win when it really counted.

1. Kuts URS 13:39.6; 2. Pirie GBR 13:50.6; 3. Ibbotson GBR 13:54.4; 4. Szabo HUN 14:03.4; 5. Thomas AUS 14:04.8; 6. Tabori HUN 14:09.8.

10,000

See Great Races #11.

1. Kuts URS 28:45.6; 2. Kovacs HUN 28:52.4; 3. Lawrence AUS 28:53.6; 4. Krzyszkowiak POL 29:05.0; 5. Norris GBR 29:21.6; 6. Chernyavsky URS 29:31.5.

Marathon

Frenchman Alain Mimoun, silver medalist in both the 5,000 and 10,000 in Helsinki, had come to Melbourne with the intention of focusing on the long track race. The marathon was an option, but not a serious one. But after finishing a disappointing twelfth in the 10,000, Mimoun decided to try to salvage his trip down under with the Marathon. This despite his lack of marathon experience.

There was no clear favorite in this event. Some experts fancied Veikko Karvonen of Finland. This very experienced marathoner had won the 1954 European Marathon as well as the Enschede, Boston, Athens and Fukuoka marathons. Perhaps the most intriguing entry was Zatopek. There was no doubt that he was past his best, but the Czech had an amazing competitive record; even his recent hernia operation did not rule him out as a potential winner.

The start, with 46 runners, has gone down in history as the only false start in an Olympic marathon. In the summer heat, the field soon spread out so that at 10K (33:30) there were ten in the lead group. Zatopek was not among them, some 17 seconds behind. Although the speed slowed in the third 5K to 17:07 (50:37), the lead group had shrunk to seven: Mimoun, Filin and Ivanov of the USSR, Kelley (USA) , Kotila of Finland, Briton Ken Norris, and Nyberg of Sweden. Zatopek was now only five seconds behind the leaders. In the next uphill 5K covered in 17:21 (68:03), Norris and Kotila dropped back, while Karvonen moved up with the lead group.

|

| Mimoun out on his own. |

The long hill that ended near the turnaround point was to be the deciding factor. Near the top of this 3.5K climb, Mimoun took off. He ran the next 5K in 16:32. By 25K (84:35) he had a 50-second advantage over Karvonen and Yugoslav Mihalic, who had moved up fast. Kawashina (PB 2:27:45) had moved up from 14th to 4th on the downhill. He was followed by Nyberg and Zatopek.

Mimoun, his head covered with a handkerchief embroidered with his wife’s initials, kept the pace going and reached 30K in 1:41:47 (17:12). His lead on Mihalic and Karvonen, who had been joined by Kawashima, was now 1:12. Mimoun was fine until 32K when he suffered a bad patch. It took him 3K to get back his rhythm. Nevertheless, his lead had still increased by four seconds at 35K (1:59:34). The 36-year-old Mihalic, now on his own in second, clocked 2:00:50, with Karvonen at 2:00:58 and Kawashima at 2:01:36. At 40K Mihhalic, who had only one marathon victory to his name, had pulled back two seconds on Mimoun (2:18:44) and had left Karvonen 53 seconds behind. After moving up from 18th to 8th between 25 and 30K, Lee of Korea continued to overtake runners and passed Zatopek into 5th place.

In the last 2K Mimoun increased his lead to 1:32. Behind him, Mihalic had a comfortable 1:15 lead on Karvonen. The fast-finishing Lee passed Kawashima for fourth. When Zatopek entered in sixth, the crowd gave him a huge ovation. Mimoun escaped the photographers to welcome him. It was the first time he had ever beaten the Czech.

1. Alain Mimoun FRA 2:25:00; 2. Franjo Mihalic YUG 2:26:32 3. Veikko Karvonen FIN 2:27:47. Chang-Hoon Lee KOR 2:28:45 5. Yoshiaki Kawashima JPN 2:29:18 6. Emil Zatopek TCH 2:29:34.

2 Comments