Bruce Tulloh Profile

1935-2018

5’7”/1.71; 119lbs/54kg

|

Bruce Tulloh became a world-class runner in the 1960s, despite having limited natural talent. When in 1955 he returned home to England from his military service in Hong Kong, he was little more than an also-ran, someone endearingly called a scrubber in British running clubs. As a 20-year-old he had barely beaten 16:00 for Three Miles (16:30 for 5,000), and his only claim to fame was a Hong Kong Three Miles title. True, he did really enjoy running, but there was no indication that within four years he would be the British Three Miles Champion and that within seven years the European 5,000 champion.

On his return from Hong Kong, he was fortunate to join a thriving running group at Southampton University. It was led by Martin Hyman, who was to become a world-class six-miler. Hyman became a close friend of Tulloh, encouraging and guiding the younger man to steady improvement. Tulloh’s dedication, intelligence and determination emerged as he developed into a world-class runner.

--

Although born into a sporting family, Bruce Tulloh was too frail for contact sports and lacked hand-eye coordination for ball sports. Running was something he could do, but he showed no special talent for it at school. It was only during his two years of Army service in Hong Kong (1953-1955) that he began to show some ability in winning the Hong Kong 5,000 title. He returned home a keen runner with a very modest 15:46 PB for Three Miles.

A pre-university season at home in North Devon saw his time come down to near 14:30. As soon as he arrived at Southampton University Tulloh joined a running group led by Martin Hyman. “We talked athletics most of our spare time, reading our training diaries, analyzing each race, comparing courses and people,” Tulloh has written. “It is this enthusiasm that helps one train hard.” (Tulloh on Running, p. 3) It was at this time that he began to train and race in bare feet. (See Box “Barefoot Bruce”)

In the next two years, he steadily improved his time for Three Miles with 14:11 in 1957 and 13:59 in 1958. In the 1957-58 cross-country season he began to excel, running fifth to Basil Heatley in one race and running third to Martin Hyman in another. Then in the summer of 1958 Tulloh won his first title, winning the Universities Athletic Union (UAU) Three Miles with 14:05.4.

-----------------------------------------------Barefoot Bruce-------------------------------------------

Bruce Tulloh was famous for running and racing barefoot. When he began competing, this practice was not unheard of, but it was rare. In 1954 Lazaro Chepkwony was the first Kenyan to run on the cinder track at London’s White City, and he caused a stir when he appeared barefoot on the start line. Not long after in 1957, Bruce Tulloh began racing barefoot and soon drew a lot of attention. Then, following Tulloh’s example, some of the UK’s top runners began racing in “bares”: Frank Salvat, Tim Johnston, Ron Hill and Jim Hogan. For a while barefoot running became a fad.

Tulloh raced barefoot throughout his long career, both on cinder tracks and cross country.

Although running shoes improved in the 1960s and became lighter, he claimed that running without shoes gave him about a 50m advantage in a 5,000 race. This claim was based on research done with Dr. Griffiths Pugh that showed “a straight-line relationship between the weight of the shoe and the energy cost of running at middle-distance speeds on a firm surface.” (“The Bare Necessities,” Athletics Weekly, 16 June 2011)

There were occasions when Tulloh felt he was at a disadvantage when running barefoot: on very loose and dry cinder tracks and on wet and slippery cross-country courses. His loss to Gerry North in the 1962 cross-country Nationals was probably due to his inability to sprint on a slippery surface. Probably the best surface for barefoot running is grass, and it is noticeable that some of Tulloh’s finest runs were done on the grass track at Southampton and on the grass tracks in New Zealand.

Tulloh had often run barefoot during his gap year when he was living in Devon. Then he tried running on “the old-fashioned black-ash cinder tracks.” Tulloh remembered, “It was okay. It was just lighter in weight. You feel freer and easier and run with a better action.” (Alastair Aitken interview) Later, after a disappointing Mile race in spikes, he ran a Three Miles in bare feet on the same day: “Almost immediately I felt lighter and easier and cruised round to a comfortable win.” (AW, 16 June 2100) He was converted. Thereafter he was Barefoot Bruce.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Breakthrough Year

After another good winter’s training (17th in the Southern Cross-Country Championships), Tulloh showed good form in the spring with the third-fastest lap in the Hyde Park Imperial College Road Relay. His training was going well: in a week in April he totaled 35 miles with four hard days and three easy days: Sunday: 3.5 miles jogging/striding; Monday: 10x440 averaging 67.3; Tuesday: 6 miles fartlek; Wednesday: 3x mile (5:00 rest) 4:30, 4:52 (into wind), 4:37; Thursday: Easy 2-mile run; Friday: Easy 2 miles fartlek; Saturday: Six Miles race in 29:40. (TOR, p, 67)

In May he had a big breakthrough in the Inter-Counties Championships at the White City, shattering his Three Miles PB by 12 seconds with 13:46.4 for fifth place. Two days later he ran the Six Miles in the same meet and recorded another PB with 29:10.6. In this race he was sixth, well behind the winner, his friend and training partner Martin Hyman (28:23.4). A week later, he retained his Three Miles title in the UAU championships with a fast finish (14:21).

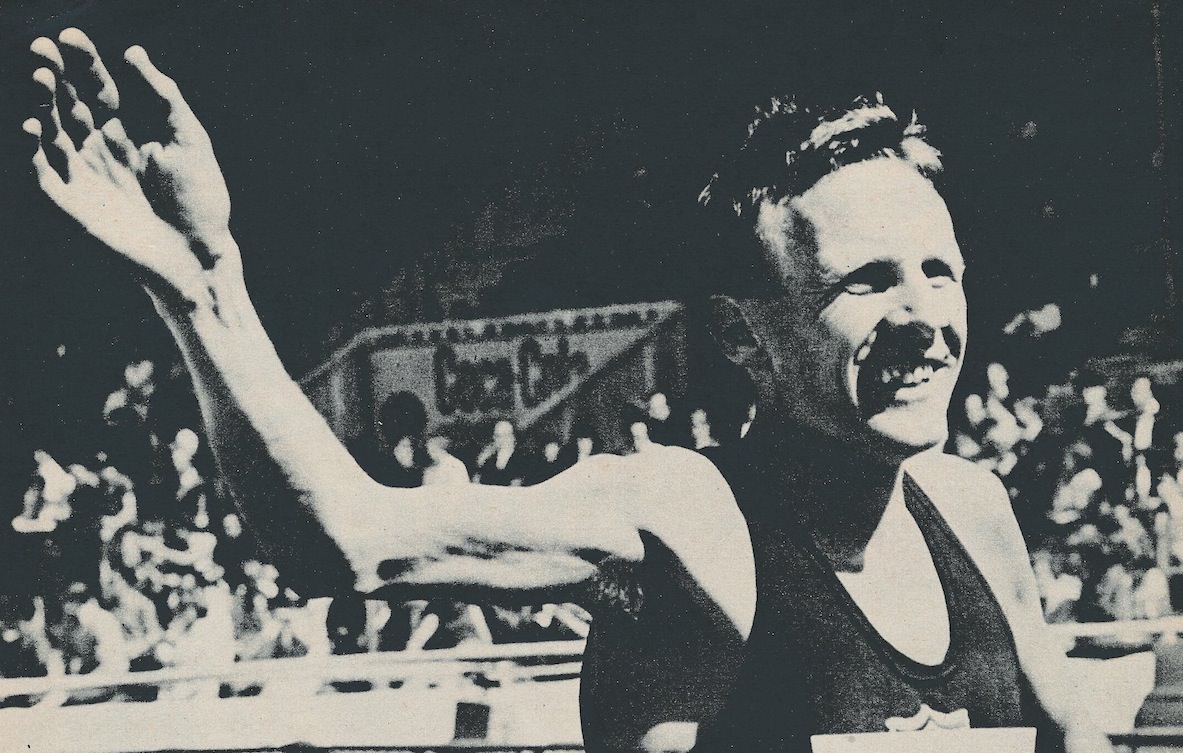

Clearly, Tulloh had moved up another level with these performances, but they were nothing to compare with what he achieved in the AAA Championships in July. According to Neil Allen of The Times, he was “the most unexpected champion of the day.” Allen described him as “gliding along as lightly as though he was a ball of gossamer.” (July 14, 1959) In the lead at the bell, he ran away from the field to record another PB of 13:31.2—a 15.2-second improvement on his Inter-Counties time. He was the British Three-Miles champion.

The reward for this win was his first British vest for a match against West Germany. He performed well in this match, finishing second to Mueller in a close race (13:31.6 to 13:32.2). After a tight Two Miles loss to Stan Eldon (both timed in 8:50.0), he went to Moscow with the more experienced Eldon as his team-mate to run against the USSR. Eldon has written about this trip in his book Life on the Run: “I introduced Bruce to the two Russians we would be competing against, as I had met them previously…. I am not sure whether they considered Bruce to be a threat as he looked like a young boy straight out of school, and I think they were even more surprised when he lined up without spikes.” (p. 85)

Eldon and Tulloh worked well together in the 5,000, taking turns leading. They soon dropped one of the Russians but had to fight it out with the other Russian, Artynyuk, in the last lap. Eldon prevailed with 13:52.8, with Tulloh (13:53.6) holding off Artynyuk (13:54.2). Apart from earning valuable points for his country, Tulloh recorded yet another PB with his first 5,000 under 14:00. His time, equivalent to 13:25 for Three Miles, showed he was running even faster than his AAA time.

But the bubble had to burst. In a 5,000 against Finland a week later, he was unable to match Eldon’s burst after eight laps. He was seven yards down on Finland’s Saloranta going into the last bend. Here is how Neil Allen described the end of the race: “Then this frail, bare-footed runner suddenly found the stuff of greatness in him again and, almost unbelievably shot through on the inside of Saloranta to take second place.” (Times, Sept. 14, 1959) 1. Eldon 13:59.6; 2. Tulloh 14:19.0; 3. Saloranta 14:19.6.

This was Tulloh’s last major race of the 1959 season—a season in which, despite having to sit his university finals, he had improved his Three Miles time by almost half a minute, had won his first national title and had proven himself on the international scene. Within a few months he had become a legitimate prospect for the British 1960 Olympic team. And if all this wasn’t enough to change his outlook, he was accepted for a year at Cambridge University.

Olympic-Year Preparation

|

|

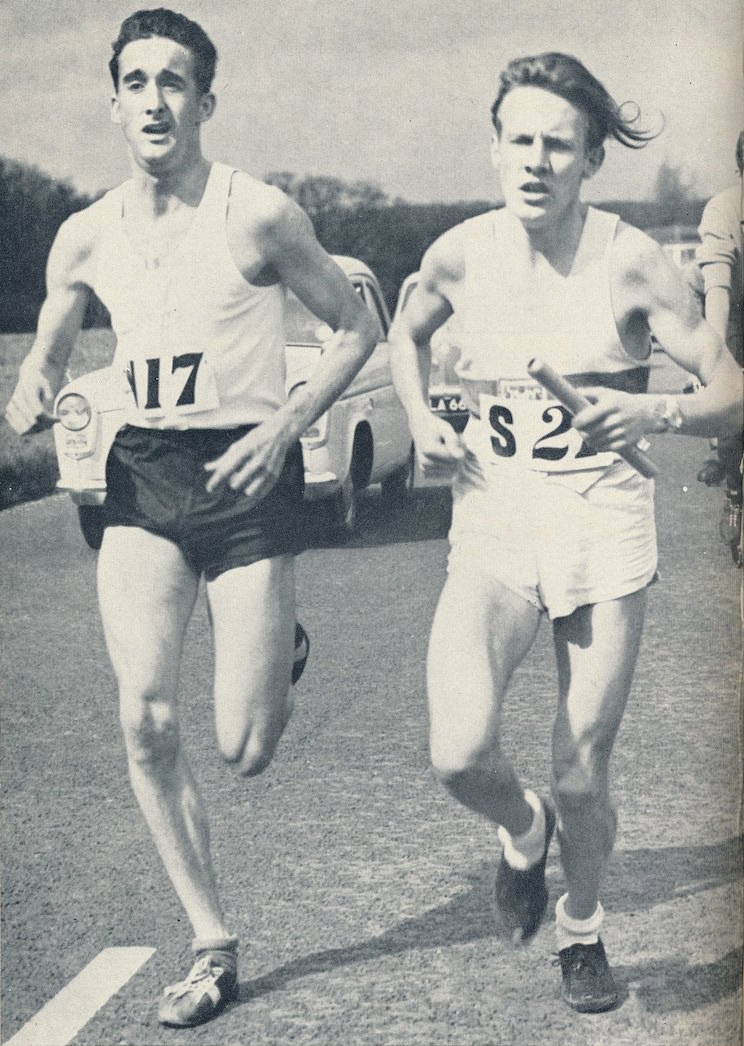

Head to head with Gordon Pirie in the 1960 London- to-Brighton Relay |

There was a thriving running community at this time at Cambridge. Mike Turner, Tim Briault and Tim Johnston were all at the forefront of the British cross-country scene. Tulloh competed regularly over the country, placing 8th in the Inter-Counties in January, 2nd in the Southern in February and 8th in the Nationals. Such was his confidence over the upcoming track season that he was reported to be aiming for a 13:00 Three Miles—10.8 seconds below Albie Thomas’s WR.

He began his track season with a 13:57 clocking to win the Cambridge trials. Four days later he ran 13:46.4. His winning ways continued with a Two Miles victory over Stan Eldon (8:46) and a 13:32.2 in the Oxford v Cambridge match. Neil Allen described Tulloh’s running in this varsity match: “Seeming as delicate as ever in appearance, Tulloh ran with strength and confidence, elbows out but motionless as though he was resting them in a sling. His bare feet pattered round the laps with a lightness that made one forget how his pace must be hurting his pursuers.” (Times, May 17, 1960)

But in his first national test of the season, the British Games, he tasted defeat twice. In the Three Miles he was outsprinted by newcomer Frank Salvat (13:50.2) and in the Six Miles two days later he ran third to Merriman (28:23.4) and Perkins (28:30.8), albeit with a PB 28:32.4.

Then after a sharpening Mile race in the Southern (4:06.6), he made an attempt on Derek Ibbotson’s Three Miles Record of 13:20.8 On his favorite grass track in Southampton, he was paced in the early stages by his good friend Martin Hyman, passing one mile in 4:28.8 and two miles in 9:02.2. This was only 13:33 pace, so Tulloh had to up the pace considerably. And this he did, covering the final mile in an amazing 4:15 to break Ibbotson’s record by 3.6 seconds with 13:17.2.

Selection and Disappointment

This time suggested that he could make the Olympic 5,000 final, but first he had to qualify for the British team in the crucial AAA meet. His main opposition for the three Olympic spots were Eldon, Salvat and Ibbotson. He was hoping that Eldon would set a good pace, but when the field passed two miles in a slow 9:10, he decided that he had to up the pace and try to take the sting out of Salvat and Ibbotson. A 65.6 lap took him clear of all the field except these two fast finishers. But he could not break them and finished third. Nevertheless he had done enough and was named to the British Olympic team a few day later.

The Rome Olympics were a disaster for most of the British team, Tulloh included. Arriving just three days before his 5,000 heat, he had no time to adapt to the August heat of Rome. Tulloh was the fastest of the three British 5,000 runners in the heats, but none of them was close to qualifying for the final: Tulloh 4th in 14:17.2; Pirie 8th in 14:43.6; Salvat 7th in 14:33.2. Tulloh was 22.6 seconds slower that his 1960 best and 9.8 seconds behind Zimny, who was the third qualifier in his heat. “I was suffering with the heat,” he later told the North Devon Journal. “[After the race] I was held upside down with a cold sponge on me for half an hour to get my temperature down.” (July 26, 2012)

A Working Runner

|

|

Inter-Counties 3: Tulloh leads Craig, Ibbotson (35) Herring and Salvat. |

Now 25, Tulloh was working full-time and training once a day in the evening, logging around 40 miles of quality running a week. The highlights of his 1961 winter were a third in the Inter-counties cross-country in January and a second in the Nationals behind Basil Heatley. These two fine runs showed he was getting stronger and augured well for the track season.

In the May Inter-Counties meet, he placed a close third in the Three Miles (13:34.2) behind Ibbotson (13:33.6) and Salvat. Five weeks later he was clearly beaten by New Zealander Barry Magee, 13:18.0 to 13:25.8. But his 1961 Three Miles time was coming down, and three weeks later it dropped below his 1960 British Record PB in a match against the USA. He was teamed up with Gordon Pirie and faced a serious challenger in Max Truex. The two Brits shared the pacemaking for the first ten laps, passing the mile markers in 4:26 and 8:54. The American then took the lead with two laps to go, but could not shake of his opponents. With 330 to go Tulloh led Pirie past Truex, but he couldn’t shake off Pirie, who bided his time round the last bend and edged ahead in the straight. 1. Pirie 13:16.4 (British record); 2. Tulloh 13:16.6; 3 Truex 13:21.0 (American record).

|

|

GB v Hungary, 1961. Tulloh leads Pirie, Iharos (3) and Rozsavolgyi. |

Tulloh confirmed he was in the best form of his life in two more races. On August 7, he gave Olympic 1,500 silver medalist Hungarian Rozsavolgyi a great race, losing only by 0.4 of a second with 14:02.6. And then on August 18 on the Southampton grass track, he broke Pirie’s new Three Miles record with 13:12.0. This was just 2.0 seconds outside the new world record set by Halberg the previous month in Stockholm.

The rest of his 1961 season was somewhat of an anti-climax. He ran in three international matches in September finishing third against West Germany (14:16.6), second against Poland (behind Zimny in 13:56.2), and first against France. Still, he had raced well through a long season and had reduced his Three Miles time by 5.2 seconds.

New Zealand Tour

As he settled down to another winter’s training, he received an invitation to tour New Zealand in January and February: “I did a bit of speed training beforehand,” he recalled 52 years later. “I only got the invitation in November. I was doing my normal 40-a-week running, mainly cross country and fartlek. I did some track running before I left. [Reading from his training diary] some 400s, a 7x900 in the park. One week I did 12x400 on Monday, 5x1500 on Wednesday, and 15x200 on Friday.”

|

|

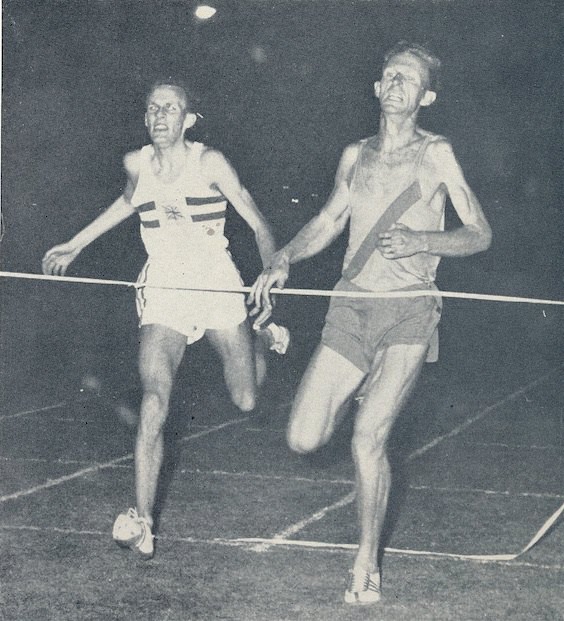

"My greatest race": Tulloh fights with Halberg all the way to the tape. |

This New Zealand tour proved to be hugely successful. In his first race, a 5,000, he faced Barry Magee and the Olympic champion, Murray Halberg: “Halberg was a very tough competitor. A very nice bloke, but like many New Zealanders, he didn’t say much--taciturn with a dry sense of humour.” Tulloh, still acclimatizing, didn’t react to Magee’s sudden surge and finished a distant third. He did however run a very fast last lap and told the press afterwards that he could outsprint Halberg. The Kiwi was up to the challenge a few days later in a Two Miles. He waited until the bell and sprinted hard: “I was aware immediately that little Bruce was right there, right on my hammer. We pounded down the back straight. He was still there. ‘Hell,’ I thought, ‘this fellow can sprint.’” (Clean Pair of Heels, p. 133) The two stayed together right to the tape, with Halberg just ahead: 1. Halberg 8:33.7; 2. Tulloh 8:33.8. Both set national records. The last lap took just 55 seconds.

Later, Tulloh described how proud he was of this Two Miles race: “This I feel to be my greatest race, not because of the times, which could have been better, but because I felt I had put the best of myself into it, and because I had come so close to beating the Olympic champion in a level race. I have always had a great liking and respect for Murray’s iron will, his refusal to be beaten. The exhilaration of that last-lap battle is something I shall always remember.” (Tulloh on Running, p. 9)

---------------------Murray Halberg’s Character Sketch in A Clean Pair of Heels, p. 132---------------------------

Bruce was a great little guy, tiny, tireless, thoughtful, ukulele twanging, with surprising sides to his character. Quite often I came across him in a hotel with his textbook and glasses, looking the complete antithesis of a sportsman, a faithful replica of the typical English university student.

But on the track he was a talented, tenacious opponent. Unexpectedly, he possessed a dry wit and a gift for foolery which was best demonstrated by an episode at Wellington airport at the end of the tour.

There, Bruce posed as an invalid in a wheelchair, wrapped in a heavy wooden rug, wearing a pathetic look and with one tiny hand clutching his beloved uke. He kept on a deadpan look of complete dejection as the tall American Jim Dupree wheeled him from the terminal across the tarmac and tenderly assisted him up the aircraft steps. Bruce loved music and he loved it generously, with a range of likes from grand opera to rock-‘n’-roll, from heavy classics to the tunes he plunked out on the ukulele.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Buoyed and more than a little surprised at his good form, he was feeling feisty four days later when he lined up against another Olympic champion Peter Snell for a Mile Race (See Great Races #15). The 800 runner had recently run an easy 4:01 and was planning to attack 4:00 On past form Tulloh, with a 4:06.4 PB, appeared to have no hope of making an impression at this shorter distance. But he had told the press, “I’ll give Snell a go, even if I don’t finish properly.” (Norman Harris, Lap of Honour, p.137) A pacemaker took the field through 880 in 1:59 but then slowed. Snell was forced to take over the lead; only Tulloh went with him.

|

|

Tulloh about to help Snell set his 3:54.4 world record. |

Snell maintained sub-4 pace and went through 1320 in 2:58. Then the unexpected happened: Tulloh bolted into the lead. Snell was glad of the help and waited until 300 to go before he made his drive. Although Tulloh was left well behind, he still finished well ahead of Albie Thomas in second place. Halberg who finished fourth, remembers Tulloh’s behaviour after he had finished: “In the middle of it all, the near-demented Bruce Tulloh danced up and down the field. ‘I must have broken four minutes. I must have. I wasn’t that far behind Snell,’ he kept saying.” (Halberg, CPH, p.135) Tulloh was right, he had become the seventh British runner to run sub-4 with 3:59.3. In front of him, Snell was just able to beat Herb Elliott’s highly respected WR with 3:54.4.

Two races down, three to go. First Tulloh won a Two Miles in 8:44.9. Then he clashed again with Halberg over Three Miles, again giving the Olympic champion a great race. The pace was on the slow side, with Halberg leading and the crowd booing him for the slow pace. But the cagey Kiwi now knew he could match Tulloh’s sprint. With two laps to go, Tulloh shot into the lead, hoping he could get away from Halberg. But he was unable to do so. Halberg waited until well into the last lap before sprinting past his rival to win with 13:30.8, while Tulloh recorded 13:32.0. Two days later, Tulloh ran his last race, winning a Two Miles in 8:39.2. He started off at WR pace—Halberg held the record at 8:30.0—but couldn’t maintain the pace, much to the relief of Halberg, who was watching from the stands.

The New Zealand tour was not only a pleasant break from the English winter but also a huge morale boost. “I surprised myself there,” Tulloh later remarked. (World Sports, 1967) And he was clearly a more confident competitor in 1962, especially with a 4-minute Mile under his belt.

Back Home

Twelve days after his last New Zealand race, Tulloh competed in the Southern CC Championships, but he had to drop out with cramp two miles out. He fared much better three weeks later in the national cross-country, finishing second to Gerry North in this very competitive nine-mile race. North had led Tulloh by four seconds going into the third and last lap. Then Tulloh had closed the gap and with his proven track speed looked the likely winner, but North, spurred by his home crowd, was the fastest finisher, opening up a seven-second gap at the finish. “I don’t hate enough, that’s my trouble,” Tulloh told reporters afterwards. “I’m tired of being second.” (Times, March 12, 1962)

Tulloh was training a little harder, but his mileage in a typical April week was only 44.5: Sunday: 13.5 miles mostly steady; Monday: Rest; Tuesday: 4.5 miles at a steady pace with a few strides; Wednesday: 5-mile straight run quite fast; Thursday: 4 miles fartlek; Friday: 10x660 (200 walk) averaging 1:43.5; Saturday: 6x80 hill, 2x900 (2:25, 2:40), 2x1320 (3:40, 3:35). (TOR, p.68)

On the track he embarked on a winning streak that didn’t end until August. He began with a pair of wins in the British Games, beating Ibbotson in the Three Miles and Hyman in the Six Miles. Both winning times—13:20.2 and 27:57.4—were excellent for the early season. His next big win was in Oslo, where he beat France’s Robert Bogey over 10,000 in 29:01.4. Back in England he won the British Three Miles title with a fast 13:16.0. In this race he showed tactical aplomb and confidence. He softened up his main rival, Bruce Kidd, with a brisk 62.6 tenth lap and then kept close to the Canadian on the last lap before decisively passing him with 60 yards to go.

First Loss of the Season

Thus far in the 1962 season Tulloh had won all his races and had posted very fast times. But on August 5th in a match against Poland, his impressive competitive streak ended. In the 5,000 race he was up against Zimny, the Olympic bronze medalist, and Boguszewicz. Tulloh knew that he would have to set a fast pace to offset Zimny’s finishing speed. Neil Allen criticized Tulloh for failing to do this: “Last season Tulloh would tie up when he had to set the pace against a dangerous opponent and now this old fault returned.” Tulloh did most of the leading, but taking the field through eight laps in 9:00 was never going to worry Zimny, even though the Pole was supposedly nursing a sore knee. The three runners were close together as they hit the bell, which meant that Tulloh not only had to cope tactically with two opponents rather than one but also had to rely on his sprint finish. As it turned out, Tulloh was third round the final bend and had to deal with the two Poles tactically running side by side in order to make him run extra-wide. Although he managed to take the lead in the final stretch, the effort proved too much, and he tied up just before the tape, allowing Zimny to come back and win the race. 1. Zimny 13:52.8; 2. Tulloh 13:52.8; 3. Bogusewicz 13:53.6.

Tulloh accepted responsibility for his loss: “I suffered from nervous paralysis and couldn’t set a fast enough pace to break Zimny.” (Times, August 6, 1962) But surely this loss was a blessing in disguise as far as the upcoming European Championships were concerned. The loss was a wake-up call. He had been winning everything throughout the summer, but now he had to seriously rethink his approach to the European 5,000 final six weeks ahead. He would have to deal with Zimny again, and he would also have to deal with the Olympic 10,000 champion Bolotnikov and with the speedy Frenchman Michel Bernard. Clearly he had the ability to win gold, but he would have to find a tactic and the resolve to carry it out.

European Title

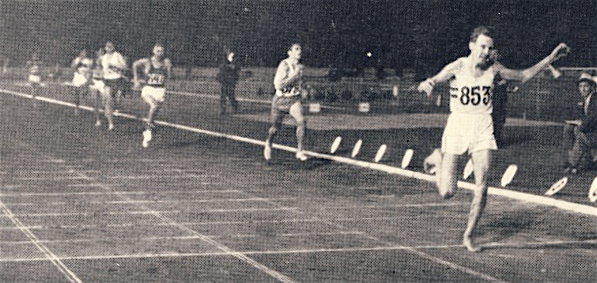

|

|

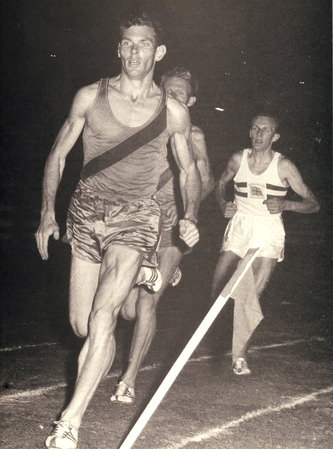

Winning the 1962 European 5,000 from Zimny and Bolotnikov. |

In fact, the barefoot Tulloh started the European 5,000 final (See Great Races #15) with three tactical plans; he would choose one of them depending on how the race unfolded. The race began at a brisk pace (29.6, 62.8) with Bolotnikov in front. But then the pace slowed drastically to a 70 lap. That was the pattern up to 3,000 with kilometers of 2:48, 2:49 and 3:01. With an 8:38.2 pace, something had to give. It was Jurek who shook things up with a 62.6 ninth lap. Asserting authority, Tulloh led the chase and soon caught the Czech. The pace slowed again; the fourth K took 2:48.2. With two laps to go (12:01) Bernard of France led Tulloh, Bogusewicz, Zimny and Bogey. Tulloh was poised to use the tactic he had planned for a slow race.

He made his move on the back straight with 700 to go, and at the bell (13:03.2) he held a 10m lead from Bernard and Zimny. It was now a matter of holding on and hoping that the advantage he had gained by jumping the field would be enough. “I was well up and could not hear a man behind me,” he recalled. “Then I started to put in a bit more effort. I knew I had a bit more extra and was fairly happy then.” (Alastair Aitken, Interview, September, 1962) He needed all the strength he had developed over the past four years, but he held on and kept the fast-closing Zimny and Bolotnikov at bay. 1. Tulloh 14:00.6; 2. Zimny 14:01.8; 3. Bolotnikov 14:02.6; 4. Bogusewicz 14:03.4; 5. Bernard 14:03.8; 6. Anderson 14:04.2. He had run the last lap in 57.4 and the last 800 in 1:59.8.

It was a wonderful victory, and it is still regarded as one of the great 5,000 triumphs of all time. Crucial to this great win was the fact that he had prepared himself mentally: “I convinced myself I was going to win.” His plan to go early if the race was slow worked perfectly; no one in the field was taking the initiative at that point. In Tulloh’s own words, “nobody…seemed to have much idea of what to do.” (TOR, p. 111)

Perth

The European race would have been a great climax to the season, but there was still another major games in 1962—the Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia. This was to be held in November, well out of season for countries in the northern hemisphere but in the summer season Down Under. Even before that Tulloh had to run for his country again in a match against Poland. And he had to compete with Zimny and Boguszewicz for the third time that year. It was another tight race, but Tulloh prevailed: 1. Tulloh 13:26.8; 2. Zimny 13:28.4; 3. Boguszewicz 13: 28.6.

By the time November came around, Tulloh was a tired man. Nevertheless, he performed well enough in the Three Miles, although he was unable to match Halberg’s 53.8 last lap: 1. Halberg 13:34.15; 2. Clarke 13:35.92; 3. Kidd 13:36.7; 4. Tulloh 13:37.91. This race must have taken a lot out of him as four days later he was last in the Mile with 4:22.1.

Low-Key 1963

|

|

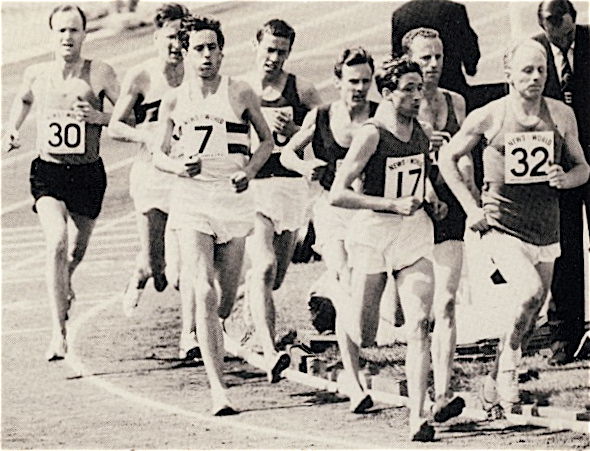

Leading Norpoth, the eventual winner, in a match against West Germany. |

Tulloh was not so prominent in the 1963 cross-country season, finishing 5th in the Southern and 35th in the Nationals. Nor was he quite so dominant in the track season. In fact he lost a Three Miles race to a fellow Briton for the first time since 1961, Don Taylor beating him in the Southern Championships (13:31.6 to 13:31.8). Then he had two major wins, first in Helsinki (13:59.4 ahead of Michel Bernard) and then in the AAA Three Miles, where he beat Taylor by 2.6 second in the fast time of 13:22.4. Thereafter his form declined in international matches with seconds against West Germany, Sweden and the USSR. For Tulloh the 1963 track season had been low-key in anticipation for the 1964 Olympics.

Increase in Training

In part, 1963 had been a low-key year because he had increased his training load from his regular 40 miles a week to “occasionally up to 60.” From today’s perspective this does not seem a lot, but it was up to a 50% increase. His low mileage had worked well for a few years, but the standards were improving all the time. He knew he had to be able to stay with a fast pace and still be able to sprint. Back in 1962 Track & Field News had questioned whether he could have won the European 5,000 had the race been “20 seconds faster.” Tulloh had to be prepared for that “20 seconds faster” in Tokyo. (The current WR was Kuts’ 13:35.0)

But this 50% increase in his training load turned out to be a mistake. “I overtrained,” he admitted many years later. “I didn’t have a coach. One of the things that a coach can do for an athlete is to say, ‘That’s it. You’ve done enough.’” With a full-time job and family obligations, Tulloh pushed himself too much in 1963 and 1964. As a result, despite all the hard work, he didn’t even make the British Olympic team for Tokyo and had to watch Schul, Norpoth, Dellinger, Jazy, Keino and Baillie fight it out for the 5,000 medals.

How much training did he do in his build-up to Tokyo? Tulloh consults his training diary from 50 years ago: “I was doing a full-time job and training after work. Here are some weekly mileage totals: 51, 61, 43, 38.5, 37, 47, 49. In a week in May I did 20x400 on Saturday, 3x900 on Sunday morning and 16x400 on Sunday evening, 8x600 on Monday, Tuesday another interval session, Wednesday a sprint session and Thursday more 400s.” That’s not excessive by today’s standards, but it was too much for Tulloh: “I pushed myself too hard. I broke down my immune system and picked up measles in the first week of June.” The measles couldn’t have come at a worse time for the Olympic tryouts.

The previous winter, when he had been training harder than ever, his cross-country performances were good, if not quite up to his usual level: 21st in the Inter-Counties (during which he was kicked in the calf), 3rd in the Southern, 7th in the Nationals and 7th in the Internationals. Neil Allen reported that in the Nationals Tulloh “drove himself so hard that he finished wheezing and doubled over.” (Times, March 2, 1964)

Tokyo Hopes

His 1964 track season began well with a victory in the Inter-Counties Three Miles (13:23.6). But two days later he dropped out of the Six Miles with five laps to go. It was after this race that his measles developed. He was out of competition for six weeks. When he returned he was unable to match Kidd and Halberg in the AAA Three Miles. And then, running in an international against Finland he managed second place, only to collapse afterwards. Things got worse in August when he dropped out of two important races. But then a glimmer of hope appeared when he ran a 13:19 Three Miles in his club championships on the Southampton grass track. “I have regained my confidence,” he told the press. “I was running really well tonight.” (Times, August 12, 1964) Clearly he was battling with his confidence as much as with his physical fitness.

Still not selected for the British Olympic team, Tulloh was given one last chance in a match against France. Sadly he had a disastrous race, finishing last in 14:47, a full 51 seconds behind the winner Michel Jazy. His Olympic dream was shattered. “It was a terrible summer,” Tulloh told Neil Allen, “but I can assure you that I never contemplated giving up.” (World Sports, 1967)

Moving up to 10,000

Despite this painful setback, the 29-year-old’s competitiveness remained. He trained through the following winter and ran well over the country with a 5th in the Southern and an 11th in the Nationals. But on the track he wasn’t the consistent winner that he used to be. He was only third in the Inter-Counties Three Miles (13:29.6), 12th and 22nd in the Helsinki World Games 5,000 and 10,000, and 2nd in a White City 10,000. Clearly his sights were focused on the major games to come in 1966.

A training week in April, 1966, shows how much he had increased his training: Sunday: 40 minutes running; 6xMile (2:00) average 4:56; 20 minutes running; Monday: am: 10x220 (0.35) 31.0 average, pm: 6x600 (1:40) on dunes, 10x220 average 31.5; Tuesday: am: 2 miles jog, pm: 3 hours walk/run; Wednesday: Brisk road run 7 miles; Thursday: 2 miles jog; Friday 8x880 (2:20) average 2:16.7; Saturday: 19-mile road run at 6:00 mile pace. Total mileage: 81.

|

|

Inter-Counties Six Miles: Heatley leads Hogan, Hill, Tulloh, Batty, Bullivant, Hyman and Turner. |

Now 30, Tulloh focused his competition on the 10,000, which was to be his event for the two major games in 1966. His track season started well with a 28:04.8 win in the Inter-Counties Six Miles ahead of Ron Hill. Then he faced the Russians Khlystov and Dutov over 10,000 at the White City. He tried unsuccessfully to break away with three laps to go and lost out to both Russians in a close finish (28:50.6). The Times reported that he “struck too early and without sufficient conviction.” (June 18, 1966) Still, he was running better than he had done since 1963, and his prospects for the Commonwealth and European Games were good, especially if he could peak at the right time.

Next came the AAA Championships which would decide the final selections for the British team. Going into the race, Tulloh had the fastest time among the Brits (27:50.6 at six miles in the Moscow 10,000 race), but he faced stiff competition from Hill, Fowler, Freary, Rushmer, Alder and Hogan. The stellar field also included the reigning champion Gamoudi and the Hungarian Mecser. A fast early pace by Hogan (8:58.8 for two miles and 13:38 for three) indicated that Bullivant’s all-comer’s record (27:26.4) was likely to be broken. In the fourth mile Alder took over, and then on the 17th lap Gamoudi went to the front. As a fast finisher, his aim was to slow the pace, which in fact he did. He controlled the race from that point and just held on after challenges first by Mecser and then by Tulloh. 1. Gamoudi 27:23.4; 2. Tulloh 27:23.8; 3. Mecser 27: 23.8; 4. Fowler 27:24.8. For Tulloh the race was nevertheless a big success with a PB and a national record.

Ron Clarke, who was watching the race from the stands, was most impressed: “It was a great Six Miles and I really mean that. Any time you get ten men going under 27:45 is a real breakthrough. Tulloh must be my chief rival for the Commonwealth Six Miles at Kingston.” (Times, July 8, 1966) A few years later Tulloh called his 27:23.8 run “probably my greatest physical feat.” (TOR, p. 7)

But Tulloh, though selected, didn’t run in the Commonwealth Six Miles. He had to withdraw at the last moment with pains in his leg. Three weeks later, however, he was ready for the European 10,000. He entered this race with the third fastest time of the year behind Haase and Roelants. After a brisk 14:19 at 5,000, Roelants broke away, but at 7,200 he was caught by a group of six that included Tulloh. Tulloh was able to stay with the leaders for two more laps but then dropped back. He finished sixth in 28:50.4. It was a disappointing performance, especially considering that Haase’s winning time of 28:26.0 was slower that Tulloh’s AAA run.

One More Season

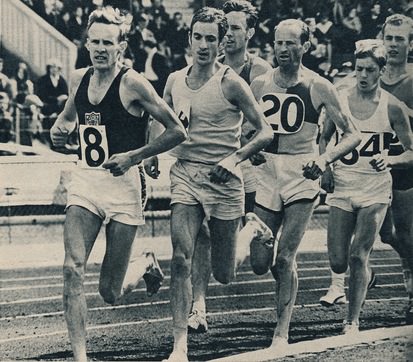

|

|

The Barefoot Brigade: Tulloh, Johnston and Hogan, all in bare feet, lead the 1967 AAA Six Miles. |

The next year was to be Tulloh’s last as an international runner. He might have continued through 1968 but, as he told Neil Allen, “I want to concentrate on making a living and I am hardly filled with enthusiasm at the thought of racing 10,000 at high altitude in Mexico City.” (World Sports, 1967) He entered the 1967 track season full of expectations after a good winter’s training. Following a warm-up Mile race (6th in 4:06.2), he won the Inter-Counties Six Miles in the excellent time of 27:42.8, only 20 seconds slower than his 1966 PB. He followed this up with a fast Two Miles win (8:35.4). But then a trip to Los Angeles to run a 10,000 seemed to break his competitive resolve. He finished 5th in a very slow 31:04. Back in Europe, he had just one more win in a match against France (13:59.2). Thus his 13-year competitive career ended.

Ultra

This didn’t mean his running career was over. He found a new challenge—not against competitors but against his own limitations. This challenge was a solo run across the USA from Los Angeles to New York. The idea started in 1967 and the run took place in 1969. Four Million Footsteps tells the story of Tulloh’s run. He wanted to beat the record of 73.3 days set by Don Shepherd in 1964. A route of 2876 miles was chosen and the start set for April. Serious training began in September 1968 after a gradual build-up from July. He had to prepare himself to run 300 miles a week. By January he was up to 130-150 a week and he discovered that he did better running shorter stages rather than longer stages.

Planning to average 45 miles a day, he set off through the urban maze of LA in good spirits, and progressed well for the first ten days. Averaging 44 miles a day, he was almost exactly on target. But then he developed problems with his left thigh and ankle. On Days 13 and 14, he could only manage 19 and 15 miles. By now he was walking a lot. Then came the rains and snow. This was the toughest period in his run. He was still “shuffling” on Day 19, but by Day 22 he was running again and hitting his 45-mile target. Then another problem: mental fatigue. But he kept to his daily quota right through to day 44, when he treated himself to a half-day break. His best day was Day 38 when he ran 51 miles.

His steady progress continued. By Day 57 he could write, “The physical side of running has been working very well. It justified my faith in the adaptability of the human body…. My body [is] now a running machine…. As long as I [keep] putting the fuel in, the miles kept coming.” (FMF, p. 154) And the daily mileage was maintained until the last day, when he had to run only 20 miles. He finished in 64.9 days and beat Shepherd’s record by 8.4 days. It had been a remarkable feat of determination.

A Full Life

In the 48 years since his retirement from competitive running, Tulloh has always kept busy. In 1971 he went to Kenya for a two-year teaching job. While there he set up the first Kenyan Pre-Olympic training camp. He also coached Mike Boit, one of Kenya’s greatest runners, helping him to win an 800 Olympic bronze in 1972. Later in 2001 he organized the Safaricom Marathon, designing a course in Kenya’s Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. The event is now in its 16th year and raises substantial money for charities.

On returning to the UK from Kenya in 1973, he began teaching biology at Marlborough College, staying there for 20 years. And, no surprise, he kept running. In the early 1980s he competed as a Master, running 32:30 for 10K at 50, 1:16 for a Half-Marathon at 60, and 2:47 for a Marathon at 58.

As well as teaching, Tulloh has always been interested in coaching. His best-known British athlete is Richard Nerurkar, who ran 27:40.3 for 10,000 and 2:08.36 for the Marathon. Tulloh published his first coaching book, Tulloh on Running, when he was 32, and has written consistently on running all his life. There are a dozen of his books currently listed on Amazon.

Conclusion

|

Throughout his long career Tulloh worked hard to develop his competitiveness. A hard taskmaster on himself, he was never happy finishing second. After finishing in second place for the second time in what was one of the most competitive races in the 1960s--the English Cross-Country Championships--he was clearly exasperated when he told Neil Allen, “I don’t hate enough. I’m tired of being second.” This comment, which he made more than once, suggests that Tulloh wasn’t innately as competitive as some of his opponents like Zimny. It is significant that the runners he most admired were tough competitors like Emil Zatopek. He also paid tribute to two Commonwealth runners: “When I look back on the athletes I’ve known, I can definitely say I admire Halberg and Elliott because of their determination. Athletics is competing. The man who has an iron will is something special.” (World Sports, 1967) But to his credit, Tulloh did develop this side of his running. And he developed it to the level that earned the admiration of one of the toughest competitors of all time—Murray Halberg.

The quality of Tulloh’s achievements should be assessed in light of not only with this competitive aspect but also his limited physical abilities. His European title, his British titles, his British records at Three Miles and 10,000, his four-minute Mile, his two second places in the English cross-country nationals, and his fine record in international four-man races rank him as one of the finest middle-distance runners of his time. His success was due in large part to his determination, a determination controlled by intelligence and fed by a genuine love of running.

9 Comments