Martin Hyman Profile

1933-2021

“I’m driven, analytical, and a keen observer.”

|

English distance runner Martin Hyman lacked basic speed. He couldn’t beat 2:00 for 800; his best 400 was a pedestrian 57.5. Yet he was able to place 4th in three major track championships, and from 1958 to 1964 he recorded times that even today would put him in the top six of the British rankings for 10,000. On the road he was considered by some as unbeatable. He had notable wins in Spain and Brazil and set many course records. Even in cross-country, which he considered his weakest event, he ran 3rd in the 1961 international championships.

Hyman worked hard to overcome his innate lack of speed. He said in a March 2016 interview, “I am not being falsely modest when I say that my physical abilities were very limited.” He also had to find room in his life for his running. As a family man with a full-time job, he compartmentalized his life into three distinct parts: “As a teacher I did everything I could to do a good job, and as a dad I did all I could. When I was actually training for an hour a day and when I was racing, I gave all my attention [to that].”

Hyman never had a coach; he educated himself in training theories, working with his Portsmouth team-mate Bruce Tulloh. Since Hyman reserved only one hour in his day for training (except for Sundays when he often ran for 2 hours or more), he devised sessions that used the sixty minutes effectively. He regularly ran around 50 miles a week and never went over 70.

More than most successful running careers, Hyman’s was based on intelligence and determination. Running became an outlet for his driven personality, and he had the self-discipline to get the most out of himself while at the same time living a full life as a teacher and family man.

--

Martin Hyman came to England from Jersey in the Channel Islands as a World-War-Two refugee. “As the Germans invaded Normandy, we could hear their big guns just across the sea,” he recalled over 75 years later. “I got out two weeks before the invasion and my father one week before. My father was a Jewish trade-union official; he would not have survived in Nazi Germany.” Martin had an unsettled childhood as he was moved to ten different schools. “I learnt some things twice,” he recalls, “and missed other things altogether.” That he managed to get to university at a time when entrance was difficult says a lot about his intelligence and industry.

As a youth he wasn’t successful in sport; he failed three times to earn his cub badge in athletics. Only running seemed to offer him a glimmer of hope: “I was a useless runner; I had very little talent apart from great determination. Because I was a weak and sickly child and wanted to prove I could do something. I was full of determination to get better.”

University Runner

So on entering Southampton University at 18, he tried out for the cross-country team: “There were ten in the cross-country club and the first eight would make the team. I made the team by beating one runner, while another dropped out sick. By the end of the season I was ranked 5th, and at end of the next I was possibly the best. In my third year I was the best in the southern universities circuit.”

In an evening track meeting with Portsmouth Athletic Club in his last university year, he beat their star runner. After finishing he was approached by Andy Gibb, the Portsmouth AC Club Secretary: “He came up to me and said, ‘D’ye want to join a guid club?’ I said, ‘I am only a weak lad and a novice, and I run for the university. And in the holiday I need a rest.’ He said, ‘I’ll give you an annual report and a fixture card.’”

National Service

Of course, Hyman joined Portsmouth AC and became one of the club’s leading lights as it developed into a top-level club. But first he had to do his national service. This was a problem because, as Hyman himself describes it, “I was a bloody conchie.” As a conscientious objector, he was stationed in the ambulance division at Linz in Austria, working with Hungarian refugees who had fled after the Soviet invasion of their country. Linz boasted the best club in Austria, so he was able to train at their track. “It was quite a right-wing club,” he recalled with a chuckle. “And there I was with a ban-the-bomb logo on the back of my tracksuit.”

On returning home to take a Teaching Diploma course at Southampton University, Hyman was still eligible to compete in university competition. He showed impressive form in the 1958 cross-country season. In February he placed 5th in the Southern cross-country race. Then he won the National Universities cross-country title.

On the track he showed even better form. To start, he placed 2nd behind team-mate Bruce Tulloh in the Inter-counties 3 Miles with an impressive 13:48. Two days later in the same meet he ran 2nd to Hugh Foord in the 6 Miles. His time of 28:32 was a great breakthrough; only four other British athletes had ever run faster. A month later, in what was really a trial for the Commonwealth Games, he was 3rd in the 6 Miles behind Stan Eldon and Foord. This run, a PB of 28:18.8, earned him a place on the England team for the Games at Cardiff. In just a few months, he had established himself as a world-class track runner.

Cardiff

|

But there was a complication: “Now it happened I was going to get married that weekend. I’d never thought that I would be running [in the Games].” Plans were easily altered: “We got a B&B for Margaret in Barry near Cardiff, while I stayed in the team accommodation. Every day we’d hitchhike round south Wales and get back at 5:00, my normal training time. I didn’t train on the official cinder track but on a grass track instead. It got in the papers that this new boy wasn’t taking things seriously.”

They obviously didn’t know Hyman. He was, of course, fully prepared. One of his preparations before he went to Cardiff was to purchase a decent pair of spikes: “The only pair of spikes I owned cost ten shillings. Some of its spikes were bent. I cycled from Southampton to the Jack Hobbs sports shop in East London [120K] with 5 pounds I’d saved from my Christmas money. Adi Dassler made a fantastic shoe for 3.50 pounds. I was going to buy a pair and use some of the change for lunch. When I got there they had an even better shoe for 5 pounds, so I bought those instead and cycled back without any lunch.”

Unfortunately, he discovered that he had made a bad choice: “The spikes were very long. I didn’t realize that they weren’t suitable for long-distance running. So my feet hurt more and more [in the race], and they were bathed in blood and blisters in the end. It was a very unpleasant experience.” Despite this, Hyman performed really well in the Commonwealth 6 Miles and almost won a medal.

“They went off fast, so I was at the back of the pack,” he remembered. “I kept thinking that I should just stick with them and that if I collapsed, nobody would hold it against me.” The start was indeed fast. Stan Eldon, who had beaten Hyman by 13 seconds in the AAA 6 Miles with a British record of 28:05, ground out the first mile in 4:34.9, which was 27:30 pace. He slowed to 9:15.6 for two miles. Then in the 9th lap Hyman himself took the lead for a short time before Eldon overtook him. At three miles (14:14) Power was in the lead and Eldon was falling back.

At four miles (19:06) Hyman was in a four-man lead group that included Power, Onentia and John Merriman. He was still there at 5 miles (24:06). “Every lap they got slower and slower,” he remembers, “so I didn’t collapse. And with a lap to go I was still with them.” At the bell (27:47), the other three took off; Hyman had no answer. He lost nearly eleven seconds to the winner on the last lap, but nevertheless was a comfortable 4th ahead of Fred Norris. He beat the Games record of 29:09 by ten seconds. 1. Power AUS 28:47.8; 2. Merriman WAL 28:48.8; 3. Onentia KEN 28:51.2; 4. Hyman ENG 28:58.6; 5. Norris ENG 29:44; 6. K Sum KEN 30:03.6.

This was an exceptional international debut for the 25-year-old. And there was more to come that season: a 2nd place behind John Merriman in the 6 Miles in the Great Britain v Commonwealth meet (28:49.2); a win in the Universities v. AAA meet (3 Miles in 13:44.0); and his first international victory in the team match against Finland (10,000 in 29:36.0). In 1958, his first serious track season, he ranked 3rd in the world for his 28:18.8 6 Miles, although 12 runners had run a faster equivalent over 10,000.

Portsmouth

Returning to the club scene once the track season was over, Hyman helped Portsmouth win the Southern London-to-Brighton Relay. He continued to compete for his club over the winter as he prepared for another track season. Together with his friend and fellow international Bruce Tulloh he worked on developing the most suitable training program for himself. “We didn’t have a coach,” he explains. “Bruce and I read all we could about training and then put our system into practice with the club. And because it succeeded, everybody bought it. Looking back, it was serendipity. We had the facilities from Andy Gibb and then Bruce and I were analytical and successful.” Hyman is especially grateful to Andy Gibb: “He created the circumstances in which we could flourish. He was a very shrewd administrator. During my career I heard from him every week. Without Andy Gibb I don’t think I would have succeeded.”

Training and Racing

Hyman usually trained alone. Occasionally he trained with Peter Clark, who was stationed nearby in Hampshire with the RAF. Sometimes Bruce Tulloh would join him for sessions. Later on, he would host his club-mates for training weekends: “The Portsmouth people would come out to my home in the country and stay the weekend, sleeping on the floor of my house. Then we’d have massive sessions.” Tim Johnston remembers one of them: “On one of his regular courses in Alton, you had to start by running through a bed of nettles - to get the adrenalin going.” Hyman claims this story is apocryphal: "It was put about by Bruce Tulloh after a problem when running along an overgrown path on a Sunday long run."

His own training sessions were not conventional. “I was always striving to find something that would solve a problem,” he explained. His perennial “problem” of course was his basic lack of speed. Hence his most regular session was speed-focused: 40x100 with 15 seconds of rest between. “That session took exactly 19 minutes and 45 seconds,” he added.

Another workout, which was designed to fine-tune his pace judgment, involved a series of “speeding up” laps. In this interval workout the aim was to run each 400 faster than the one before. He would award himself a point for each lap that was faster than the previous one, and he would penalize himself a point if he went slower. The aim was to get as many points as possible; this required him to start at a reasonably slow pace and then get minimally faster each time. His points record for the session was 23. “If you think about that,” he said, “[this session] requires a very, very precise pace judgement that you must apply even though you are getting progressively more fatigued.”

Hyman also developed workouts to improve his ability to change pace quickly, an ability he needed since he couldn’t rely on a sprint finish. This lack of speed required different race tactics. He did not, as many expected, set a fast pace and try to kill off the opposition. He was well aware of the price that leading exacted: “I knew that it was harder to lead than to follow because you had to push air aside. Griffith Pugh did experiments in a wind tunnel with a treadmill and a cut-out of a runner in front. He discovered exactly what I had found: that if you led at 10K pace, you had to run fractionally faster than one second per lap. I knew that. Commentators often asked why didn’t run alongside the leader to put pressure on him; that was nonsense.”

So Hyman’s favoured tactic was to draft behind the leaders, thus saving one second per lap. Then, based on his pace judgment, he would make his effort somewhere in the last few laps. He was an amazingly consistent competitor. “There was something about me that in training I ran below myself and in racing above myself,” he explained. Tim Johnston, a fellow Portsmouth runner, has also noted this aspect: “His training was not particularly impressive, but he was a completely different person in races.” (Personal email)

Seasoned International

During the 1959 track season, Hyman ran his specialty five times and won three times. He began with a convincing 6-Miles win in the Inter-Counties meet (28:23.4). In this race he broke away from the field with Eldon before the two–mile mark. When Eldon faded, Hyman stayed ahead for the rest of the race. Next in a match against East Germany, he faced top 5,000 runner Friedrich Janke, who defeated him comfortably 29:44.6 to 29:50.0 over 10,000.

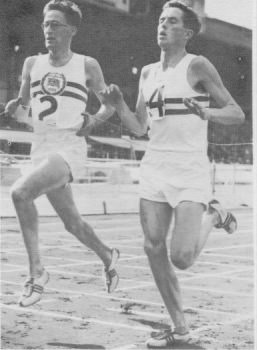

|

|

Hyman and Mike Bullivant win in a dead-heat in a 1959 match against Poland. Note Hyman's high-stepping running style. |

Six weeks later he teamed up with Mike Bullivant to race over Six Miles against Poland. According to The Times, the pair achieved “the outstanding performance by Britain.” (15 Aug. 1959) They were not tempted by the fast pace set by Stanislaw Ozog. The Pole ran a fast 4:31 for the first mile and was 8 seconds ahead after six laps. Hyman and Bullivant, running an even pace, gradually closed in on Ozog and caught him on the 13th lap. Ozog was still with them at 5 miles but he was broken on the 22nd lap. The two Brits ran as a team the whole way to the tape to stage a dead-heat and a PB for both of them, 28:16.2. The Times called the dead-heat “a wonderful gesture to the team spirit that had bound them together for such a magnificent victory.” (15 Aug. 1959) This race has often been referred to as a classic example of how to run a two-a-side distance race. For Hyman, Bullivant was the ideal partner: “I was very comfortable competing with him as a team mate,” he says. “Whatever we agreed to do, Mike would do his side of the bargain.”

After racing several times over shorter distances to keep sharp, Hyman went to Moscow to race against the great Pyotr Bolotnikov. The Russian started fast, while Hyman and Bullivant stuck to their even-pace schedule. This enabled them to catch Bolotnikov on the 13th lap. Bolotnikov made his move with just under two laps to go; Bullivant was dropped but Hyman stayed with the Russian. At the bell Hyman couldn’t match Bolotnikov’s speed, and although he was well beaten 29:18.2 to 29:24.2, he finished well ahead of Bullivant (29:38.0). The next weekend Hyman ran another 10,000 against Finland in Helsinki’s Olympic Stadium. This time he not only won but also set a stadium record and a Finnish All-comers Record. 1. Hyman 29:18.0; 2. Rantala FIN 29:21.0; 3. Merriman 29:24.6.

His good form continued in a 3 Miles at the London v Stockholm meet at the end of September. He ran a lifetime best of 13:29.2 behind Pirie and Eldon. He was leading on the last lap, only to be passed by both of them in the run in. It had been another successful season both competitively and time-wise. He had improved his 6 Miles by 2.6 seconds and his 3 Miles by 4.8 seconds. His 6 Miles time ranked him third in the world; his 29:18.0 for 10,000 ranked him 5th.

Brazil

As usual he kept in shape through the winter with weekly club competition on road and country. “At the end of the track season,” he said, “I always looked forward to cross-country although I was a lousy cross-country runner. Between the country and track I loved road races. I was much better at road races than anything else.” His success on the road led to a unique opportunity: “Jack Crump phoned me with a race invitation because I was catching people’s eye in road races.” The England manager invited him to compete in the prestigious San Silvestre New Year’s Road Race in Sao Paulo. World Class runners were regularly invited to this race; previous winners included Heino and Zatopek. His first time there in 1960 could have been more successful had he not arrived in Sao Paulo just 8 hours before the race, due to an engine fire in his plane. Nevertheless, he led for most of the race, only to blow up and finish 3rd behind Suarez of Argentina.

It was a good start to the Olympic year, but then he had a setback when injury forced him to drop out of the Southern cross-country race after four miles. He announced that he might have to call off his plans for the Rome Olympics as his achilles was limiting his training and requiring cortisone injections before competition. Fortunately the problem abated and he was fit for the British Games 6 Miles in June. But it was a tactically slow race and Hyman was left back in fourth place behind Merriman, Perkins and Tulloh after a fast finish.

Towards Rome

Olympic selection was up for grabs five weeks later in the AAA Championships. Three main contenders faced Hyman: Gordon Pirie, at 29 near the end of his career but still looking for an Olympic gold; John Merriman, an up-and-coming runner who had won the Inter-Counties Six; and Stan Eldon, the current champion. With some fast finishers in the race, a brisk early pace was expected. But the halfway point was reached in only 14:09.8. Hyman led at 4 miles (18:55.4) and was 3rd at 5 miles (23:36.4). He led down the back straight of the final lap, but both Merriman and Pirie were with him. As the three came into the final 100, Pirie went past both him and Merriman “as if they had been mere mortals instead of two of the best distance runners in the world.” (Times, 15 July 1960) Hyman did well to hold off Merriman. 1. Pirie 28:09.6; 2. Hyman 28:10.2; 3. Merriman 28:10.8.

When in Rome

This race earned him a place on the British Olympic team. Sadly his preparations were far from ideal. He was unable to train on a cinder track in the weeks leading up to the Games. And then the trip to Rome was a nightmare: “They didn’t ask when I wanted to go. They just said, ‘You’re going three days before your race.’ There was no time to acclimatize. It was a horrible experience, like being in prison. It wasn’t like that when I ran for my club and we controlled what we did. The track was hard and I had terrible blood blisters. I didn’t enjoy it whatsoever.”

The Olympic 10,000 was a tactical affair. “They didn’t go off very fast,” Hyman recalls, “so I had to make the pace. I knew I’d be gunned if I didn’t.” The early pace was steady but then it slowed: 2:48, 2:49, 2:52, 2:55, 2:58. This took the pack of 20 through 5,000 in 14:22. After doing some of the leading himself, Hyman was still in the pack at 7K after Ks of 2:56 and 2:53. The pack was down to 14. Then Dave Power made his move; only five went with him: Bolotnikov, Desyatchikov, Grodotzki, Merriman and Hyman. The next two K’s of 2:50 and 2:52 broke the two Brits. Hyman, now back in 6th, had to hang on; just three people passed him. He finished ninth in 29:04.8, behind Merriman (28:52.6) and ahead of Pirie (29:15.2). This was a PB for him by 13.2 seconds and superior to his 6-Miles PB of 28:10.2. Again he had performed well in a major games.

Club Loyalties

After his stressful experience in Rome, Hyman returned to club running on road and country. The Portsmouth club was his anchor, as was the support of Andy Gibb. “Being in the club took the pressure off me,” he explained, “and without Andy I don’t think I would have succeeded.” Hyman was unusually committed to his club: “In cross-country races, I often used to find our 6th (last counting) runner, and I helped him to join up with our fifth runner. Then I’d go up to the next two and join them up too. Because I wasn’t considering myself all the time, it took the pressure off me.”

|

|

Handing over to Bruce Tulloh in the London-Brighton Relay |

The new cross-country season turned out to be his best ever. It started with a good win in Belgium over an international field. Then in the Hampshire championships he lost his title when his club tried to dead-heat five members, including Hyman, for 1st place. The officials wouldn’t co-operate and separated the five finishers. Hyman wasn’t designated the winner. Next he won the Southern title, making his effort with just over a mile to go and opening up a 60-yard margin. “This was probably my best cross-country run,” he claimed. “There was an exceptionally strong field including Pirie, Tulloh, Perkins (the national champion), Hogan and Edelen.”

British Record

This great form continued on the track. He finally won the Inter-Counties Six with a UK record of 27:54.4. This eclipsed Eldon’s 28:05 record and made him the first Briton to break 28:00. Only four had run faster (Iharos, Halberg, Power and Stephens). The pace was fast from the start as Hyman and Bullivant took turns in leading. Soon only Basil Heatley was able to stay with them, but he was dropped just after 3 miles (13:58). Hyman and Bullivant continued working together through 4 miles (18:37.6) and 5 miles (23:19), consistently maintaining 70-second laps. It was not a team-race this time, and Hyman emerged as the stronger as he moved away from the Derby man with two laps to go. He had a 30-yard lead at the bell, but he was hurting and needed the encouragement of the crowd and the athletes on the infield to finish. He once stumbled against the curb, but he held on. Bullivant, who had contributed so much to Hyman’s run, came in second in 28:05.4, more than ten seconds back.

In the best form of his life, Hyman looked a cert for the AAA title, but he had to withdraw because of hay fever. A week later he had recovered and ran for the UK against the USA in the 6 Miles. Teamed again with Bullivant, he ran another fast race (28:07) in tying for the win. The first American was lapped and finished 1:48 in arrears.

The 1961 season wasn’t over. After pacing his friend Bruce Tulloh to a British record in the 3 Miles (13:12), he won three internationals. Against West Germany he purposely tied with Heatley—though the officials made him second—in 30:05, more than a minute ahead of the first German. Two weeks later Hyman took on the much stronger Russians and ran superbly to defeat Khazin in the fast time of 29:02, the third-fastest UK time ever behind Merriman and Heatley. To complete the season, Hyman dropped to the 5,000 and ran 14:05.8 behind Tulloh and Robert Bogey in a match against France.

Beating Bikila

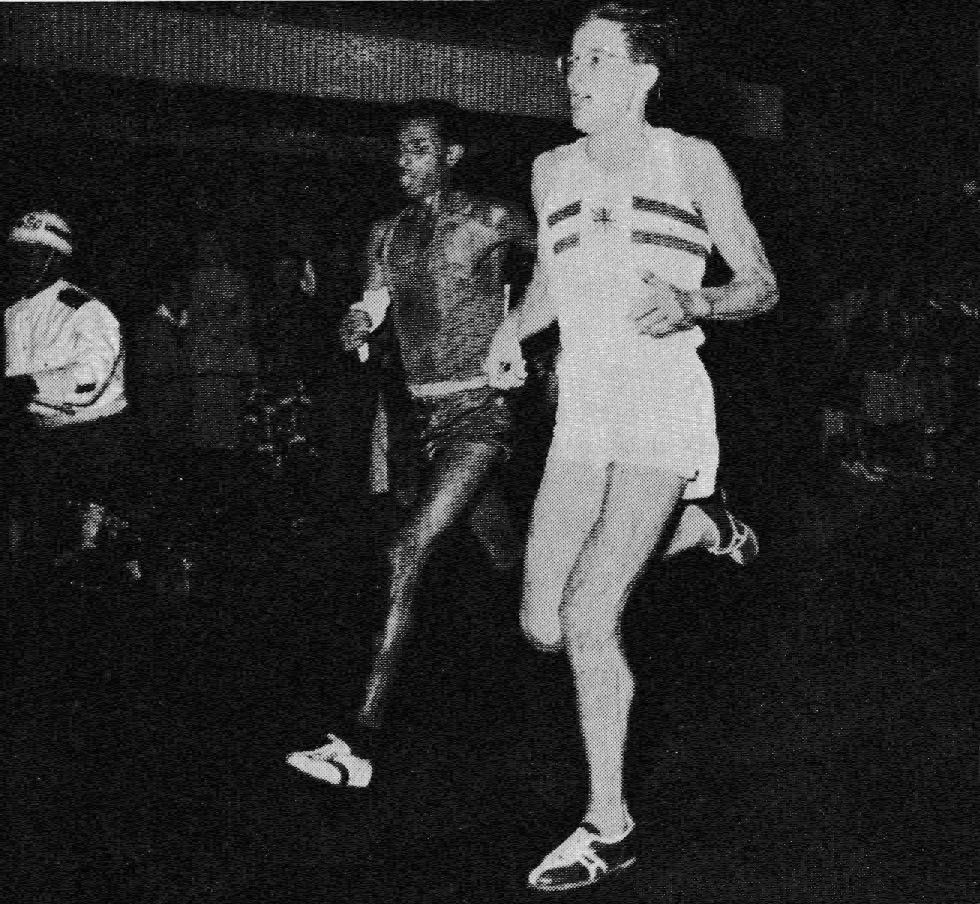

|

|

Hyman's finest moment: He "breezes" past the great Abebe Bikila |

Although the track season was over, Hyman’s incredible stretch of great races continued. In fact, the road race that he won three months later he considers his greatest. This was the 1962 San Silvestre 7.4 Road Race on January 1. For his second race there he was able to organize an ideal preparation: “I did everything right. I travelled there when I wanted and was even able to take my own beer because I didn’t like the local brew.” Because he arrived well before the race, he was able to train on the street course, which was closed to traffic six days before the race, and to watch his main rival, Abebe Bikila, the Ethiopian Olympic champion. Bikila, of course, was the strong favorite. During his practice runs, he discovered a tactic to beat the Ethiopian: “I noticed there was a hairpin bend just before you came into the finish. I noticed Bikila used to run wide round that hairpin in practice. I reckoned that I could run close in the camber of the gutter, accelerating round there into the last 100 to the finish.” As it turned out, although he ran the hairpin as planned, he didn’t need to use this ploy to escape from Bikila.

|

| The finish in Sao Paulo |

Early in the race, Hyman stayed back: “The start was an enormous rush; I didn’t take part in that.” As the race progressed, he moved through the field: “Eventually there was somebody 50m ahead silhouetted by the searchlight. When I got up to him I realised it was the lead runner, Bikila. It was about a mile from the finish. I got in behind him quietly and got some shelter. He didn’t notice. Suddenly he became conscious of me and leapt in the air and sprinted. He was shocked. I let him go and continued steadily until I caught him again. He leapt in the air again but less energetically this time. This happened three times.” Hyman had the great Bikila at his mercy. “We came to a T-junction not far from the finish, and he was on the wrong side of the road, so I dropped back a little and cut across so that when we came to the junction I was meters ahead of him. I went like hell, did my bit round the hairpin and beat him. He was a far better runner.” 1. Hyman 21:24.7; 2.Bikila 21:29.8. Hyman’s time was a course record by 13 seconds; it stood until 1965, when Gaston Roelants ran 21:20.

Another Busy Year

Although he was home a week later winning the 1962 Hampshire cross-country title, the high-level of his racing subsided. He was only 42nd in the Inter-Counties cross country and 8th in the Southern, where he suffered a cut knee. He was 45th in the Nationals, doing his bit for his club. That spring he began competing in a new form of racing—indoor track. The longest indoor race was a 2 Miles. Although rather short for him, he nevertheless excelled, running a good 8:57.2 behind Derek Ibbotson and earning an international vest against West Germany. In that race he finished 3rd behind Ibbotson and Kubicki, improving his best indoor time to 8:54.2.

|

|

Finishing second to Bruce Tulloh in the 1962 Inter-Counties 6 Miles. |

With this indoor racing and some early 2 Miles outdoors, he was sharp for the Inter-Counties Six in June. His friend Bruce Tulloh, who had already won the 3 Miles two days earlier, also entered this race. The two Portsmouth team mates—Tulloh was running for Devon—worked together. The pair didn’t follow the fast early pace of Hogan (4:34.2 at one mile), but by the halfway point (14:00) they were with him out ahead of the field. With Hyman and Tulloh taking turns to lead the trio passed 4 miles in 18:41 and 5 miles in 23:25.2. With a mile to go, Hyman started to up the pace, causing Hogan to drop back. The Hyman-Tulloh cooperation was abandoned at the bell, when Hyman had to make his effort in order to negate Tulloh’s fast finish. He tried valiantly down the back straight, but Tulloh was not to be dropped, and he passed Hyman in the last 70 for the win. 1. Tulloh 27:57.4; 2. Hyman 27:58.4; 3. Hogan 28:08.2.

Hyman’s chances for his first AAA title looked good as no one except Hogan had been close to him in the Inter-Counties 6. But he was in for a surprise. Although he PB-ed yet again, he could only manage third place. This AAA 6 Miles was described at the time as the greatest ever run. It was certainly fast and exciting. Hyman’s old rival Merriman set the pace for the first 14 laps, passing miles in 4:33, 9:15.6, 13:38 and 18:18.6. In the closing stages Hyman was battling it out with Roy Fowler, Mike Bullivant and Mel Batty. He led at the bell from Fowler and Bullivant. And although he worked hard down the back straight, Bullivant passed him before they entered the last bend. Then Fowler made his move on the bend, bumping Hyman in the process and forcing him to break stride. As Bullivant and Fowler fought for the victory, Hyman held on well for third to qualify for the Europeans. 1. Fowler 27:49.8 (2nd fastest ever) 2. Bullivant 27:49.8; 3. Hyman 27:52.0; 4. Batty 28:56.6.

Euro 10,000

Such was the depth of British distance running in 1962 that while Hyman could finish only 3rd in the AAAs with a time of 27:52.0, he ran a wonderful 4th in the European Championships. The race was tactical, which was to his disadvantage. Bolotnikov, the world-record holder at 28:18.8, roared off with a 63.4 lap and passed 1K in 2:45.3 well ahead of the field. Only Janke responded to the Russian’s pace, and soon the two were running together. Hyman was too far back to join them when their pace slowed; he was still 10 seconds off the lead at the bell. In the last lap, while Bolotnikov went on to a clear victory, Hyman and Fowler battled with Frenchman Robert Bogey for bronze. Janke, who was broken by Bolotnikov at the bell, only just held on for second, while Fowler and Hyman both managed to pass Bogey to record an identical time. Thus Hyman missed a major-games medal by a whisker. 1. Bolotnikov 28:54; 2. Janke 29:01.6; 3. Fowler 29:02.0; 4. Hyman 29:02.0; 5. Bogey 29:02.6.

Perth

Hyman had another chance at a major medal in Perth two months later. In the 6 Miles he faced the Canadian Bruce Kidd as well as the 1958 champion Dave Power. For Hyman the Perth race was oddly similar to the Euro race. While the two leaders (Kidd and Power) were well ahead, he again had to fight it out for third place, this time with Welshman Merriman and Kiwi Barry Magee. The only difference was that this time he finished fifth rather than fourth. Still he was only 1.17 seconds short of a bronze medal. 1. Kidd 28:26.6; 2. Power 28:33.53; 3. Merriman 28:40.26; 4. Magee 28:40.53; 5. Hyman 28:41.43 28:42.3; 6. Batty 28 47.15.

But Hyman’s games weren’t over. He was asked to run the Marathon, despite never having run one. He agreed to run for his country. “I’d never run more than 11 miles in my life. I didn’t realise you were supposed to drink. I became dehydrated; it was 41 degrees and there was no shade.” Planning for his first marathon, he decided he was capable of running the distance at 6-minute-mile pace. On the lap of the track at the start, he was right on pace with 89.5 and well behind everyone else. But he kept going and finished in 9th place with 2:32.06.2. He was only 1:15 behind England’s specialist marathoner Peter Wilkinson. As it was the only marathon Martin Hyman ever ran, he describes his modest time as both a PB and a PW (personal best and personal worst).

1963

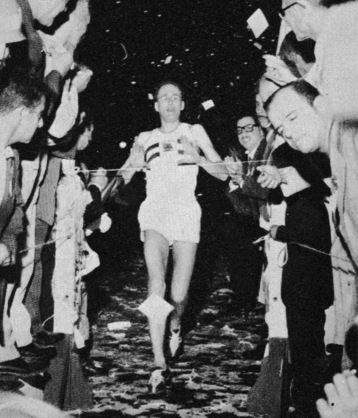

|

|

Hyman and Bullivant win for their country again. |

After such a hectic year that began with his win in Brazil and ended with his marathon in Perth, Hyman was quieter in 1963. In fact he had made a big decision on his running career: “I got better every year until 1962. I did everything I could all my life to run faster. I’d tried everything from training twice a day, to doing more mileage, to even eating more vegetables. But in 1962 I didn’t get faster, so I gave up trying. In 1963 I’d given up trying to get faster and was enjoying my club running, being in the best distance running club in Europe. I was still churning up reasonable times, but I had given up. I wanted to go on running my whole life, but I wasn’t interested in improving.”

On the country his best run was 3rd in the Southern. On the track he ran two important races in July. First was a 10,000 in Moscow that saw him take 3rd place in 29:24.4, well behind Bogey (28:48.2) and Ivanov (28:48.4). He ran a little faster in the AAA 6 but finished well back in 7th with 28:14.2, which was 24.4 seconds behind the winner Ron Hill. It was a modest year for the 30-year-old Hyman, but the next year was an Olympic year and offered a chance to improve on his ninth place in Rome.

Dreams of Tokyo

Hyman began the 1964 cross-country well with a 7th place in the Southern. He ran even better in the Nationals, finishing 10th his second-best placing. For a while it looked like he might be competing in the International race, but he ended up as travelling reserve.

As in 1962 he ran some indoor races in the spring and recorded his fastest 2-Mile time of 8:50.2. His first big test over 6 Miles came in the May Inter-Counties meet, where there was a strong field of Olympic hopefuls. Hyman must have been pleased with his 28:29.0 second place behind the fast-finishing Ron Hill (28:26.8) and in front of Hogan, Heatley and Bullivant. The Times reporter saw Hyman “showing an inspiring return to form.” (19 May 1964) Although he was no longer trying to improve, to “get faster,” he was still clearly training hard.

The big test was the AAA 6 Miles on July 10. With Olympic selection on the line—although the first three in the AAA were not automatically chosen—the pace was really hot. In fact, all the leading runners were in new territory with the fast pace. Two miles in 9:04.7 and three in 13:42.8 had the leaders on 27:26 pace—well inside Fowler’s 27:49.8 UK record. As the race progressed, Bullivant and Hill were out on their own, chased by the trio of Fowler, Hyman and Freary. This trio finished ten seconds behind the front pair at the tape, with Hyman sandwiched between Fowler and Freary. Amazingly he had broken his own PB for Six Miles by a huge 16 seconds to record his lifetime best of 27:36.0. But his great run was almost unnoticed in the excitement of one of the great races in British distance running. “The 27:36 was a surprise to me,” he admitted. “I suppose it also happened that I didn’t have to lead. There were a lot of better runners there, so I could just follow.” 1. M Bullivant 27:26.6 (UK and European record); 2. Hill 27:27.0; 3. Hogan 27:35.0; 4. Hyman 27:36.0 PB; 5. Freary 27:37.6; 6. Kilby 27:53.

Although Hyman was fourth, he was the third Briton as Hogan was Irish. So he was still expected to be on the Olympic team—especially so in view of his great time breakthrough. But the selectors decided that the 31-year-old should make way for youth, and Fergus Murray was selected to run the Olympic 10,000 with Bullivant and Hill. “I sent him a cable wishing him well,” Hyman recalled. “I was chairman of the International Athletes Club. We campaigned against practices of the Board taking the fees that we were due every time we gave an interview. A fee was paid but we weren’t told about it. They kept it.” This wasn’t the only issue that Hyman campaigned over: “I wasn’t popular; that was the reason I wasn’t selected. And I was never selected after that. It was totally political.”

Club Man to the End

Hyman continued running, but his focus was now mainly on his Portsmouth AC club. In January of 1965 he helped Portsmouth win the European cross-country title, finishing fifth in the race. He ran 21st in the Southern and 27th in the National cross-country races, again scoring valuable points for his club. And on the road he helped his club finish 4th in the National London-Brighton. He was still fast on the track, running a respectable 28:08 for third in the AAA 6. But his international career was over—apart from the occasional cross-country race in Europe. The next year he was still fit enough to place 25th in the National CC championships.

As he entered his late thirties, he still continued to train an hour a day, run for his club and coach young runners. At the same time, he worked on the administration side of his sport. For close to ten years he was chairman of the International Athletes Club. He also had a long association with the British Orienteering Squad: "As founder, running coach, chairman and treasurer, I tried to progress the Squad from a very low level to world class. I left when professionals were appointed to run it."

|

After he retired as Assistant Head at Inveralmond High School, Hyman continued coaching runners. He has now been holding interval-training sessions in Edinburgh for 35 years, “every Tuesday without fail.” Occasionally over 100 runners have attended. And just as he had his own views on training himself, he has a different approach to coaching: “I believe passionately that, because everyone is unique, it is ridiculous for a coach to tell a bunch of people with whom he is not familiar, all to do the same session. I try to explain available options for training and criteria for choosing which option to take. [So] my aim as a coach is to move away from the traditional coach role of telling youngsters what to do and towards empowering youngsters to decide where they want to go and to think about how best to get there. That way they will not just keep coming for as long as they are happy to be bossed by adults, but will have the means of being active for the rest of their lives.”

Conclusion

Martin Hyman was one of the best distance runners of his time. His achievements were highly respected by one of his Portsmouth colleagues, Bruce Tulloh: “Hyman would be the first to admit that he has little natural running ability; in addition he has been perennially handicapped by asthma in the winter and hay fever in the summer. For him to reach international level was a triumph of determination and intelligent planning.” (Tulloh on Running, p.4) Of course, Hyman not only reached international but excelled there. His three fourth-place finishes in major games attest to his competitive success at the top level.

Hyman was also a fine club man. He was a major factor in the success of Portsmouth Athletic Club. “I ran for them every week unless I was running for GB or England,” he asserted. “It wasn’t a sacrifice; it was a joy and a pleasure.” Hyman saw his many commitments during his competitive years as an advantage. He found he was less stressed than the full-time runners. He recalls arriving at the White City an hour before his race. “When you got there you saw the Russians and the Americans sitting there scared stiff. They’d been in a training camp for a fortnight thinking about nothing but the race.”

The 82-year-old Hyman prefers to live in the moment. “I do not care much for what I have done as an athlete,” he said. “My preoccupation is with coaching.” Such is his focus on the present that he was unable to recall anything about his fourth place in the 1962 European 10,000. But this wasn’t because of a failing memory. Hyman is just so committed to his athlete-centred coaching.

54 Comments