GORDON PIRIE PROFILE

1931-1991

Gordon Pirie’s serious running career began when, as a 17-year-old, he witnessed Zatopek’s 1948 Olympic performances: “My imagination was set on fire and my consuming ambition was born. I instantly recognized him as the embodiment of an ideal for myself as he scorched through the 10,000 field. From that day he has never ceased to be my greatest inspiration and challenge and my firm friend.” (Pirie, Running Wild, p.16) Not endowed with great natural ability, Pirie achieved success through following Zatopek’s example: “He burst through a mental and physical barrier. He showed runners that what they had been content with up to then was nothing to what could be achieved.” (RW, p.16)

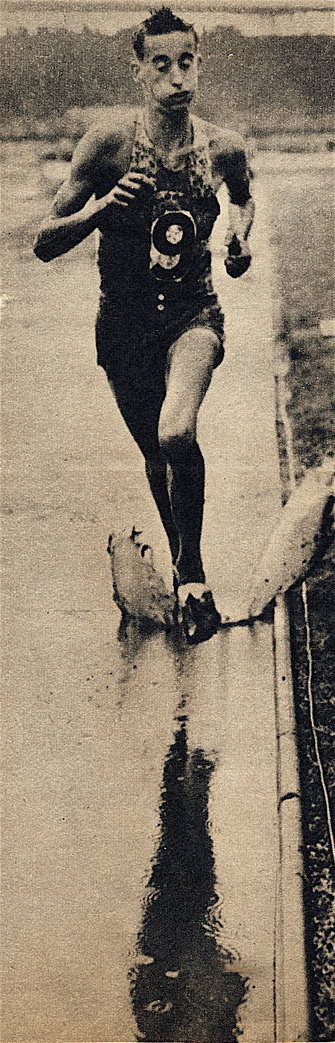

|

| Puff-Puff Pirie. |

Although Pirie came across to many people as having no interest but running, he was in fact well rounded and well-read. Not fortunate enough to get to university, he harbored some class resentment towards Oxford runners like Bannister and Chataway. His father came from a social class that at the time never considered a university education. But his father was a runner who covered ten miles a day, a considerable amount for those days. It was his father who started Pirie’s interest in running.

Early Development

Over the four years following his seeing Zatopek at the Olympics, while he worked as a bank clerk and did his two years’ National Service, Pirie gradually built up his training load to a level close to Zatopek’s. But he hadn’t followed the Czech’s schedules: “I adopted his attitude and ideas, and satisfied myself that his method of long, hard and frequent training was right for me.” (RW, p.18) Such hard self-coached training, Pirie qualified for the Helsinki Olympics at 21.

In this four-year period between Olympic Games, his times had improved to the following: 28:55 for Six Miles, 13:44 for Three Miles, and 3:57/4:14 for 1,500/Mile. At Helsinki he ran 30:04.2 for 10,000 and 14:18 for 5,000, both just outside his equivalent non-metric PBs. These times were especially impressive because he ran both races to win, not just to record a good time. He stayed with the leaders of the 10,000 for 6,500m, going into the lead for a short period before being dropped and finishing seventh. In the 5,000 final, he took the lead as planned with three laps to go, but as in the 10,000 his lead was short-lived; when he was passed, he fell back to finish 4th. These were fine performances for an inexperienced 21-year-old; it was clear that Pirie had arrived on the international scene.

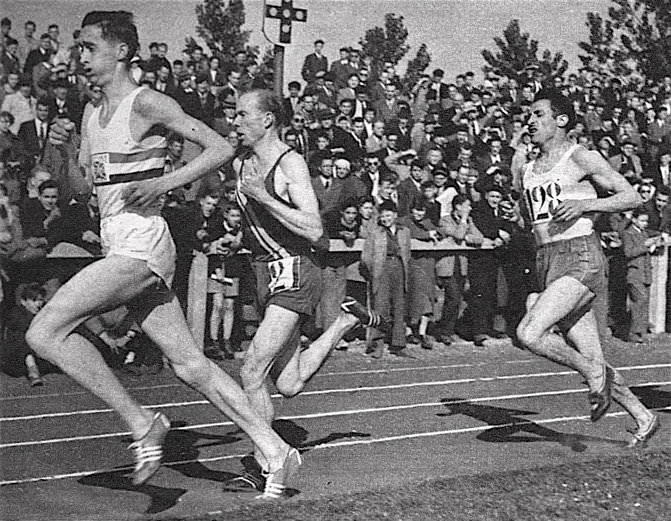

|

| Pirie leads Reiff and Mimoun. |

Gerschler

Immediately after the Games Pirie met the German coach Woldemar Gerschler (See Profile) for the first time, a meeting that would have a huge influence on his career. At the Helsinki airport, Pirie overheard Gerschler talking to Oxford runners Bannister, Brasher and Chataway. He heard how Gerschler had trained the surprise 1,500 winner Barthel. “I had a quiet talk with him,” Pirie wrote in his autobiography, “and from that day he was my adviser and coach.” (RW, p.95) They kept in touch by monthly letters. It took Pirie a year to save up enough money to visit Gerschler in Freiburg, Germany.

From that day in 1952, Pirie followed Gerschler’s advice faithfully. He would visit the coach in Freiburg whenever he could. “Gerschler was the first man who ever suggested that I could do more than I was trying to do,” he wrote. “[He] took over the enormous responsibility for training which I had borne so far.”(RW, p.19) Gerschler never told Pirie how to race, just how to produce “the maximum effort.” Pirie often stressed that enjoyment of training is essential: “To avoid boredom and staleness in training, I have always consciously developed the sheer enjoyment of rhythm, speed, excitement and achievement on the track, no matter how many times I do the same thing.” (RW, p.27) Pirie believed in training on the track—where he would race. His dedication and heavy work loads were often derided. Throughout his career charges of overtraining were leveled at him whenever he failed to meet expectations.

|

| In England colours at the White City. |

Banner Season

Under Gerschler’s guidance, Pirie performed brilliantly in 1953, with two WRs and ten British Records. He reduced his Six-Mile time from 28:55 to 28:19.4, his Three-Mile time to 13:36 (14:02 for 5,000) and his Mile to 4:06.8 (3:52 for 1,500). Second in the 10,000 world rankings and fourth in the 5,000, he was now at the top. At the end of the 1953 season he finally managed a visit to Freiburg for a meeting with Gerschler and Herbert Reindell, a heart specialist. He was tested for two days and told he had the strongest heart they had ever encountered. On the third day he was tested on the running track throughout a session of 25x200 in 28 seconds. An electrocardiograph was set up trackside and after every five intervals he lay on a stretcher and had his heart monitored. All the testing enabled Gerschler to devise the best training schedule for Pirie.

Injuries

Over the next winter Pirie trained hard and changed jobs, becoming a rep for a paint company. Sadly, Pirie’s track season turned into a disaster. A foot injury in May interrupted his training, and then he cracked a foot bone in a race. Pirie claimed this injury cost him “at least two or three years’ progress” in his running career. The season was virtually a write-off, though he did run some reasonable times on the track in October and November.

After winning the 1955 National cross-country title, Pirie was close to his Six-Mile PB as early as April with 28:21.4. In June he worked on his speed with 1:53 in the 800 and a 4:06 mile. But this promising start did not lead to great things. He did improve his Three-Mile time to 13:29, but he passed out from dehydration with a lap to go in the AAA Six Miles. Later in the season he lost to Kuts over 10,000 and to Zatopek over the same distance. The season ended on a better note when he ran a British Record for 10,000 in 29:19, but this was only equivalent to his Six Miles WR two years earlier. Overall, 1955 must have been a disappointment to him. He made matters worse by running a two-hour track race in late October. After this race, he wasn’t able to run again until the following February.

World Records

Using a special weight program to rehabilitate and strengthen his legs, he cut down on his racing in the early 1956 season. Four races over One Mile and 1,500 sharpened him, and he ran a 4:03.6 PB Mile. Then, in 5,000 race, a world record came out of the blue. He went to Bergen to race European 5,000 champion Kuts. The Russian refused to let Pirie lead. They stayed deadlocked until the last lap when Pirie sprinted the back straight and left Kuts so far behind that he was able to ease up in the last 100, unaware that he was inside the world record. His time was 13:36.8, almost four seconds inside the previous best by Iharos. Three days later, Pirie had another close battle, this time over 3,000 with Jerzy Chromik of Poland. This brought him another world record with 7:55.6, equaling the world record of Iharos.

But the best was yet to come. Pirie went to Malmo in July to race three Hungarian WR holders—Iharos, Rozsavolgyi and Tabori--over 3,000. He won this race in a new world record of 7:52.8, with a last lap under 55. It was now less than three months to the Melbourne Olympics; Pirie must have felt really confident. However, Kuts’s stunning 10,000 WR of 28:30.4 in September must have dented that confidence somewhat.

|

| Desperately Hanging on to Kuts in the 1956 Olympic 10,000. |

Melbourne 10,000

On November 23, Pirie and Kuts lined up for the 10,000, one of the most famous races of all-time. (See Great Races #11) Such was their rivalry that they raced each other without a thought for the rest of the field. It was an epic struggle in which for once the front runner broke the chaser. Pirie, with greater speed, used the correct tactics of staying close behind Kuts, but he wasn’t quite strong enough to withstand his rival’s repeated bursts. Just when the Russian thought he had failed to break Pirie, he suddenly found himself alone. Pirie, totally exhausted, dropped to 8th at the finish. With his superior track speed, Pirie should have had a better chance against Kuts in the 5,000, but Chataway let Kuts open up a gap at the front, and Pirie was unable to re-establish contact. The fact that Kuts won from Pirie by eleven seconds suggests that Kuts would still have won even if that crucial gap had not been allowed to open.

Waning Powers

These two defeats by Kuts broke something in Pirie; he was never quite the same again. After a long break, he coasted through the 1957 track season, running a lot of shorter distances and reducing his Mile time to 4:00.9. He ranked only 10th in the world for 5,000 with 13:58.6, 22 seconds below his best. The 1958 season was better but still mediocre, although he did rank #1 for the 5,000, with a “slowish” time of 13:51.6. He ran in the Cardiff Empire Games, finishing fourth in both the Mile and the Three Miles. And he finished third in the European 5,000 in 14:00.6. But it was clear that he was no longer the dominating runner he had been in the summer of 1956.

It looked like Pirie’s career was winding down. In 1959 he could run no faster than 14:29 for 5,000 and 8:08 for 3,000. However a 13:25 Three-Mile victory at the end of September showed he could still win races. His good form carried over into the Olympic year. He won the 3,000 in the British Games in 7:57 and won the AAA Six Miles in the good time of 28:09.6. A 5,000 victory in 13:51.6 just before the Rome Olympics augured well, but the heat of Rome in August was too much for him. He couldn’t even qualify for the 5,000 final and was tenth in the 10,000 in 29:15.6. His 10,000 time was a personal best, but his tenth place showed that the world leaders had overtaken the 29-year-old; he was over half a lap behind the first three. One recompense was that he broke the four-minute mile in Dublin after the Games—by a whisker in 3:59.9.

Lasty Gasp as a Professional

He wasn’t quite done yet. On July 22, 1961, Pirie, now 30, ran a British Three Mile record of 13:16.4. It was about ten seconds slower than his 5,000 WR, but it was an indication that he was still near the top.

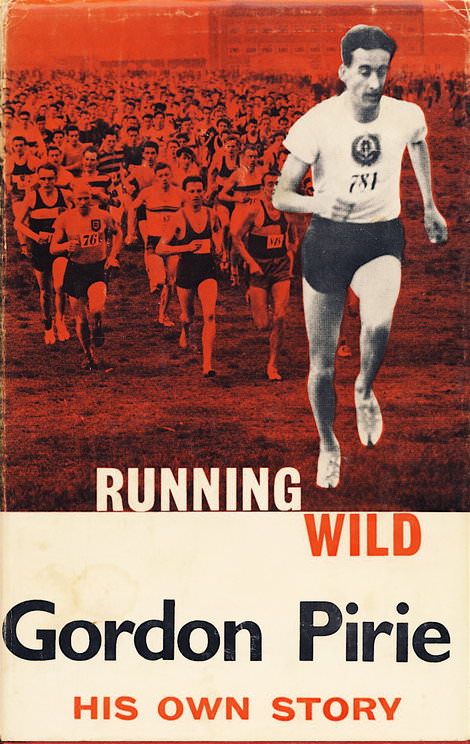

|

| Pirie's book that was published in 1961. |

Then he became involved in an allegation that he had received money in Scandinavia. He refused to meet the British board and was dropped from a National team. However, he was allowed to run against the USSR late in the season. This was Pirie’s swansong—a spirited 5,000 victory with a 56.7 last lap. After this he turned professional, in an attempt to reap something from his years of hard work. He ran in front of football crowds, and even went to Spain to run 10,000 on the sandy surface inside a bull ring in Barcelona (he lost to two Spanish runners each running 5,000.). In December his victorious last race against Russia was deemed ineligible because of a newspaper article in which he had stated that he had received money in Scandinavia. It was a sad ending to a brilliant career. But he did find one way to exploit his running competitively—orienteering. He became very successful at this Scandinavian sport, winning national titles in 1967 and 1968. Over the next 20 years he scratched out a living coaching. Sadly, he was a bankrupt living on social assistance when he died of cancer in 1991.

Conclusion

Pirie’s personality was an essential ingredient for his success. He always spoke his mind and was often involved in controversies. “No track and field athlete in Britain—indeed, no sportsman—makes headlines with greater regularity than distance-runner Gordon Pirie,” wrote Denzil Batchelor in 1955 (World Sports, Oct. 1955). His outspokenness grew out of his courage and intensity. These qualities enabled him to continue Zatopek’s quest to find the limits of human endurance.

20 Comments