Albie Thomas: Profile

1935-2013

|

When 21-year-old Albie Thomas of Australia burst on to the international scene with a fifth place in the 1956 Olympic 5,000, coach Percy Cerutty considered him the “best runner, technically speaking, in the world today.” (Middle-Distance Running, pp.49-50) Eighteen months later, Thomas fulfilled the great promise Cerutty had seen in him with an amazing 59 days of racing on the European circuit, during which he won nine of 16 races. In these races he not only broke two world records (Two Miles and Three Miles) but also won two Commonwealth Games medals, broke the Australian 3,000 record, ran a 4-minute mile, paced Herb Elliott to both his Mile and 1,500 world records and won the Three Miles in the British Games.

Today a 23-year-old would still be expected to improve. But 50 years ago there were no full-time athletes. Thomas always needed to earn a living before he thought about his running career: “We went to work and trained in the dark at night,” he recalls. Further, Thomas married in 1958 and soon there were two children to support. So although he continued serious competition until 1966, and although he stayed at world-class level, he never quite matched the form of those 59 glorious days in 1958.

Early Years

Albie Thomas had a tough childhood. “When I was in primary school,” he remembers, “my mother died. I got farmed out to an auntie for 12 months. My father had boarders. It wasn’t easy. That’s the way it goes. It doesn’t kill you.” After finding he was too small to excel in rugby league, he joined St George District Athletics Club at 16. Competing on a grass track that was 5 1/3 laps to a mile, he ran barefoot until he was able to buy a second-hand pair of spikes.

A visit to Cerutty’s Portsea training camp in 1953 was a turning point in his running career. Infected by Cerutty’s enthusiasm and his ideas, Thomas went home and started training on sand dunes and doing weekly long runs with the Randwick Botany Club. Of course, Cerutty was over 800km away and unable to supervise his training, but he kept in touch with the young Sydneysider. “He sent me training programs,” Thomas explains. “I used to write to him detailing the training I’d done. He’d say that’s pretty good and would maybe add something.” At first the progress was slow: Thomas’s best Three Miles time in 1954 was only 15:24.8.

Thomas persevered and a couple of years later, he began to emerge as one of Australia’s best middle-distance runners. In the 1955-6 track season he started off with an 8:54 Two Miles, and then in February 1956, he knocked 30 seconds off his Three Miles PB with 13:36. His reputation grew. He was recognized as a tenacious competitor.

Melbourne Olympics

Thomas, however, still didn’t believe he could make the Australian team for the Melbourne Olympics. In fact, he bought tickets to watch the Games. Cerutty, who has written of Thomas that he was “victim of an upbringing where he could not truly believe that he could be great,” had done all he could to give Thomas self-belief. So everyone was delighted when Thomas ran third in the Olympic trials after John Landy decided to focus on the 1,500.

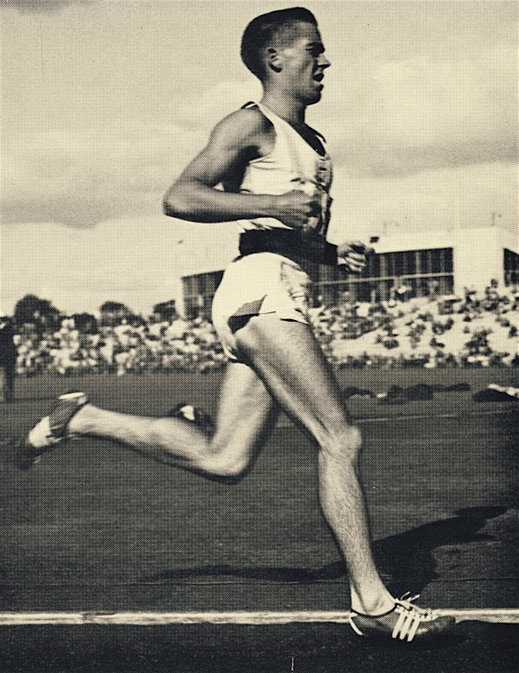

|

| Winning his 5,000 heat in the 1956 Olympics. |

At Melbourne, he won his Olympic 5,000 heat. True he ran 15 seconds faster that he needed to (14:14.2), but he was a young man competing in the Olympics in front of his home crowd. Norris McWhirter described the crowd during Thomas’s heat as “vociferous, with the little 126 lb Aussie engineer Albert Thomas pistoning around accompanied by feminine and juvenile screams of delight.” (Track and Field News, December 1956) The Aussie home crowd had good reason to scream because he not only won his heat but also broke the Olympic 5,000 heat record.

Thus Thomas lined up in the 5,000 final as the youngest and least experienced competitor. The main focus was on the rivalry that has already been established in the 10,000 between Vladimir Kuts and Gordon Pirie. Also in the field of 14 were Ibbotson, Chataway, Szabo, Tabori, Schade and Bolotnikov. He was up with leaders from the start. He was fourth at 1,000 (2:40.1). But the torrid pace of Kuts left him 5m behind the leading trio at 2,000 but still in fourth place. In the next K, as Chataway moved up with the leaders, Thomas (8:17) was six seconds behind the leading quartet, but only Szabo was with him. At 4,000 he was still in fifth place, now15 seconds behind Kuts, who was now out on his own.

Over the last K Thomas and Szabo had their private battle. At the bell they passed an exhausted Chataway; they were now racing for fourth. Thomas held off the Hungarian until the last 150, but nevertheless finished in fifth place. Such a high finish was totally unexpected. As a bonus, he had also beaten Zatopek’s Olympic record with 14:04.6. And to show that this great run was not a flash in the pan, he won a post-Olympic Three-Miles races in Sydney, beating the Olympic bronze medalist Derek Ibbotson.

The next year, 1957, was a consolidation year. He improved his 3 miles by 10 seconds to 13:25.9 and ran a promising 4:01.5 mile. But there was no clear indication of the great year ahead in Europe.

World Record

In July 1958, after a long 48-hour journey from Australia to London, Thomas went to Belfast for his first race, a Mile victory in 4:07.4. He traveled down to Dublin the next morning and then went sightseeing before his evening Three Miles race at the new Santry Stadium. His main opponent was Aussie, Merv Lincoln, who was really a miler. Asked many years later why Lincoln was running the longer distance, Thomas replied, “Blowed if I know.” Anyway, Lincoln blazed out a good pace and took Thomas through two miles in 8:52. “I took over with three laps left, thinking, ‘Bugger this, I’m going to have a go here.’ That’s when Dave Power on the inside of the track yelled to me, ‘If you can keep going, you can get the world record.’ That was the big stir.’” And Thomas certainly stirred; he ran the last mile in 4:19, with a last lap of 62.8, to set a new WR of 13:10.8, beating Iharos’s mark of 13:14.2. There had been no plan to attack the world record.

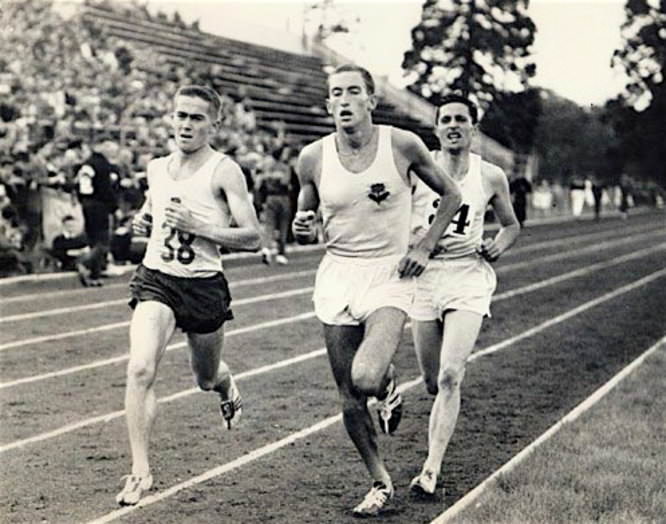

| Dublin Mile: Leading a star-studded field. Elliott Lincoln, Halberg and Delany follow. All were under 4:00; Elliott broke the WR with 3:54.5. |

Two weeks later, Thomas was lining up in the Three Miles final of the Commonwealth and Empire Games. As world-record holder he was now the favorite. Pirie had a faster time (13:36.8 over 5,000) but he was not in form. Nor was Derek Ibbotson, who had won the 5,000 bronze in Melbourne ahead of Thomas. Thomas led the field for the first mile in a brisk 4:18, well below his world record pace. But then he slowed. No one else was willing to lead. So he was still in front at two miles (8:55.6) with five runners, including Pirie and Ibbotson, on his heels. In the ninth lap, Halberg of New Zealand moved to his shoulder and then sprinted flat out. “He done me like a dinner,” Thomas ruefully admits. “Once he got away, I knew I wasn’t going to catch him.” Halberg had a nine-second lead at the end; Thomas had to be content with a silver medal. Thomas respects Halberg but he still takes pleasure in the fact that it took Halberg many attempts over the next three years to break his Three Miles world record.

Thomas’s Games weren’t over. He also won a bronze in the Mile behind fellow Aussies Elliott and Lincoln with a 4:02.77 clocking. A week later he was running for the British Commonwealth against Great Britain at the White City. His main opponent was Stan Eldon, the British Six-Miles record-holder (28:05) who had made a valiant attempt to break the field at Cardiff: “Eldon used to surge. What I did when he surged was to run up on my toes to make it look as if it was stupidly easy. When he eased off, I would take off. I didn’t give him a rest. He would come back, but he didn’t last all the way.” Thomas finally broke way for an impressive tactical victory in the good time of 13:20.6.

Running Technique

Running form had been important to Thomas from his early days. “I practiced technique,” he explains. “I call it running tall and running light. Tall means you upper body is up off your hips. That means you are running light; you are running over the ground, not on it. It’s lifting your body up. If you sit on your hips you’re going to plod. If you lift yourself, the knee comes up and you have a longer stride.” And he absorbed Cerutty’s ideas on arm movement: “They come up to the center of your chest and then go back past your hip. It’s like the other two legs of the horse. Percy used to write to me a lot about horses.” But it’s running tall that he thinks is the key: “You’ve only got to look at the Africans, even up to the Marathon. They’re running so cool and light. I’ve taught all the kids I’ve coached to run tall.” His old rival Murray Halberg has cheekily paid tribute to Thomas’s running style, describing him as “Pacing along like a little cock sparrow in his usual crisp style.” (Halberg, Clean Pair of Heels, p. 71))

Another World Record

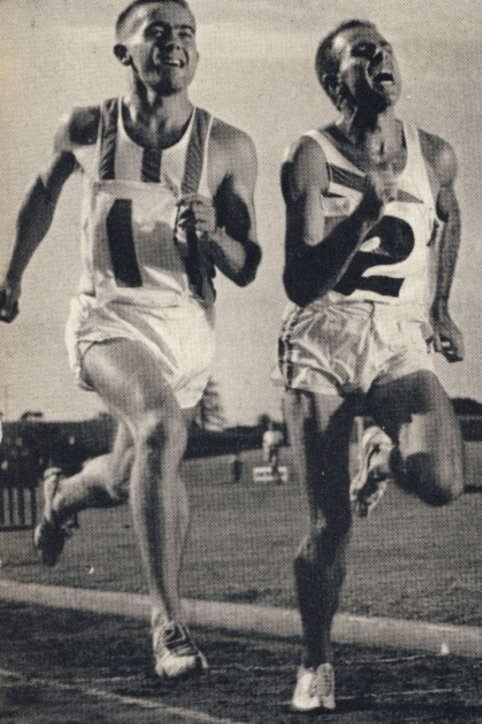

|

| Two Miles WR: Thomas about to surge past a tired Elliott. |

Then it was back to Dublin’s Santry Stadium for a Two Miles race. “On the plane to Dublin, Percy asked me if I would pace the Mile and Herb would pace my Two Miles the next night. Well, I had run a Mile in Belfast and the next day I ran my 3 mile WR. So thought, what the heck, and agreed.” (Thomas, letter to Bob Phillips, October 8, 2010) In a packed Santry Stadium, Albie did his job well. Although his first lap was a trifle fast (56.0), he took the field through 880 in a perfect 1:58. Thomas however wasn’t one to give up. He held on after Elliott and Lincoln flew by and was still third going into the last bend. And although he was then passed by Halberg and Delany, he surprised himself with a 3:58.6 clocking. It was his first four-minute mile, and he had also helped Elliott to shatter the world record by 2.8 seconds.

Such a big effort didn’t bode too well for his attempt on the 8:33.4 Two Miles world record the following evening. And it didn’t help that a tired Herb Elliott was unable to do much to help with the pacemaking. He took Thomas through the mile in 4:22, a good six seconds too slow: “When I heard the time I thought, 'That’s gone out the bloody door,'” Thomas remembers. But he made the record still possible with a 61 lap. Elliott led again for half a lap, but the pace slowed to a 67. Thomas needed to run the last two laps faster than 2:03.4. And he did with two 61s and a final world-record time of 8:32.0.

For the next four weeks Thomas raced in Scandinavia and Germany. The races were mostly low-key, but he did participate in a major 1,500 in Gothenburg, where he helped pace Elliott to yet another world record. In a field of seven world-record holders, Thomas worked his way to the front at 200 and took Elliott through in 56 and 1:57. The Aussie went on to a 3:36 world-record clocking (Jungwirth’s WR was 3:38.1), while a tired Thomas jogged home in 10th place. Three more races completed Thomas’s wonderful season. He returned home to his job and married life.

Working Family Man

Thomas continued to race at a high level for the next eight years, But as a married man with a full-time job and two children, he was unable to match the incredible form of the 59 days in 1958. He did represent his country in the next two Olympics, but the results were disappointing. In the 1960 games he was eliminated in the heats of the 1,500 (5th in 3:46.8) but in the 5,000 he reached the final, only to finish a distant 11th. “The competition had got tougher,” he admits. Then in 1964, when he was running faster than any time since 1958, he got sick after arriving in Tokyo and was eliminated with times that suggest he shouldn’t have been racing at all. Even in the 1962 Empire and Commonwealth Games in his home country, he could place only 5th in both the Mile and Three Miles.

|

| Two fierce competitors:Thomas and his friend Dave Power. |

But these performances were only disappointing after his great 1958 season. On closer scrutiny, it is clear that he still performed consistently well for someone who worked full-time, supported a family, and later on went to night school as well. Sensibly, in view of his commitments, Thomas decided to focus more on the Mile: “I always did look more toward the mile.” This meant he could still be competitive without putting in a lot of miles. And competitive he was, winning the Australian Mile title four consecutive years from 1961 to 1965. And he was under four minutes in three different years (1960, 1963 and 1964), placing him high in the world rankings.

Thomas had always wanted to work for Australia’s prestigious airline Qantas. And in 1966 he was hired by them. At this point he decided to retire from serious competition. But he still ran: “You’ve got to actually enjoy it. If you don’t enjoy your running there’s something wrong.” As well, he maintained his membership with St. George District Athletics Club and began coaching.

Thomas is just walking for exercise now. He had a pacemaker installed after bypass surgery in 2004. Following retirement from Qantas in 1993 after 26 years, he maintained involvement with his club and recently celebrated 60 years of membership. He can look back on a wonderful career which brought him in contact with some wonderful people. “I think I competed in the best era,” he says nostalgically. He talks fondly of “Gentleman John Landy” and “Gentleman Ron Delany.” He proudly recalls how he managed to meet his hero Emil Zatopek at the 1956 Olympics and get the Czech’s signature in his copy of the Kozik biography. He speaks highly of his early mentor Percy Cerutty: “He was 50 years ahead of his time. He was good to everybody.” And he is in regular contact with his old friend Dave Power: “An extremely bloody tough competitor.” Thomas was a tough competitor himself, and he will always be remembered as a double world record-holder and as one of Australia’s all-time great runners.

Postscript

Albie Thomas died in 2013.

Note: Unless otherwise stated, quotes are from a December 2011 telephone interview with Albie Thomas.

5 Comments