Lasse Viren Profile

b. July 22, 1949

This great Finnish runner will not be remembered for his three world records. Rather, his name will always be associated with the four Olympic gold medals he won at two consecutive games in the 5,000 and 10,000. Lasse Viren’s wins in Munich in 1972 and in Montreal in 1976 were controversial as he rarely showed top form in other races. But he was only interested in the major meets and had the discipline to train for long periods without peaking or racing at his optimum level. New Zealand coach Arthur Lydiard has paid tribute to Viren’s “systematic training” and has called him “perhaps the finest distance runner the world has ever seen.” (Garth Gilmour, Arthur Lydiard, p. 149) American Frank Shorter, who raced against him and trained with him on occasion, saw Viren as the complete runner: “He has had everything it takes to win—the talent, the intelligence, the determination, the discipline, and in innate tactical sense of his competitors’ weaknesses.” (Olympic Gold, p. 107)

-----

|

| Lasse Viren with this coach Rolf Haikkola |

Lasse Viren was born in Myrskylä, a rural Finnish town of 3,000 situated 80K north-east of Helsinki. One of four brothers, he had a typical Finnish childhood. He was involved in sports and cross-country skied from an early age. After leaving school early, he helped out in the family trucking firm. In his spare time he enjoyed running from time to time.

The first indication that he had talent came when at 15 he ran 2:57.2 for 1,000. However the next year he was only 13th in a youth cross-country race. He was running 10-15Ks two or three times a week: “I just ran whenever I had time,” he recalled, “and because I enjoyed it.” (Matti Hannus, Finnish Running Secrets, p. 47) He began to get more serious after watching Perrti Sariomaa from his home town compete in the annual meet against Sweden. The next year he ran 9:17.0 for 3,000, but this ranked him only 13th in Finland as a youth. His training started to show results when he placed second in the Finnish Youth cross-country race. “I was very surprised,” he says. “I had not been training so much.” (Hannus, p. 47) This performance led to invitations to training camps, where he received training advice for the first time. Later that year, near his 18th birthday in 1967, he broke 15:00 for 5,000 with 14:59.4 and ran 3,000 in 8:32.8. Both times were Finnish under-18 records.

At the end of the 1967 season, his progress was interrupted by a year’s compulsory military service. He did run during this year, sometimes very hard, but his next season saw no improvement over 3,000 and 5,000. Still, he ran 4:04.0 for 1,500 and 32:18.8 for 10,000. An eleventh place in the Finnish Junior 5,000 championship race was disappointing, as it was his most important race of the season. (Hannus, p. 49)

Perhaps due to the hard training in the Army, he had a breakthrough in 1969, his last year as a Junior. His first race was a huge PB: a 3,000 in a Finnish Junior record time of 8:13.8. Over the summer he improved this record to 8:06.8 and then 8:05.2. His 8:05.2 came in the ISTAF meet in Germany, where he placed 7th. He also went on a record-breaking spree over 5,000, beginning with 14:23.2 and then 14:17.0, 14:09.4, 14:08.0 and finally an eye-popping 13;55.0. On top of all this record-breaking, he won both the Junior and Senior Finnish 5,000 titles and earned himself three Senior national vests for matches against Norway, Sweden and Great Britain. It is noteworthy that in the annual match against Sweden, which Viren regarded as the major international of the year, he won his first international race, beating Najde, Vassala, Vaaitanen, Edberg and Ekman. Thus in the space of four months in 1969, Viren had emerged as an international-class runner, having just turned 20.

Altitude Training

|

|

A 20-year-old hopeful: Lasse Viren in 1969 |

At this point Viren was being advised by Perrti Sariomaa. They decided that he should accept a track scholarship from Brigham Young University. This American university had established a good relationship with Finnish athletes and there were already some notable athletes like Jaako Tuominen, Perrti Pousi and Altti Alarotu studying there. The Utah university is situated 65K south of Salt Lake City in Provo. The most appealing aspect from Viren’s point of view was that Provo is 1,465m above sea level. Thus while running for BYU—and perhaps studying (he had very little English at this time)--he would be accumulating months of altitude training.

Viren stayed at BYU from late October 1969 to the spring of 1970, nominally training under Coach Sherald James and competing in cross-country and track. He later complained of the interval–training he had to endure there, and he found it difficult to avoid running on the roads. (Hannus, p. 50) His focus, clearly, was to build up his mileage and to condition himself for the 1970 European track season. As was often to become his habit, he used competition as training, and never excelled in a BYU vest. Dave Hindley, a British distance runner at BYU who was to place second in the NCAA 10,000 twice, remembers the 20-yearold Viren as having “long spindly legs and a weak upper torso.” What impressed Hindley was Viren’s personality: “He was determined, single-minded, perhaps to the point of cynical. Oblivious to others’ perceptions, I think he reveled at BYU in his linguistic isolation--an excuse for doing his own thing.” Viren confirmed this later in Seppo Luhtala’s book Top Distance Runners of the Century: “The time I spent in the USA…was an important period for me, helping me mentally in many ways.” (p. 318)

Hindley recalls that Viren used to run about 17 miles daily—a lot considering the Provo altitude. He once raced Viren in a 2-mile race in the BYU fieldhouse (sawdust track—5 laps to a mile). Viren ran 3/4 of a mile at world-record pace, then blew up and jogged: “He didn't care. He had ultimate self- belief; nothing mattered to him except the big one.” Hindley ran against Viren many times that winter and spring, and he beat the Finn every time except once in a Two Miles when he had already run a 3,000 Steeplechase.

Back in Finland

Viren returned home from the USA for the 1970 track season. At this time that he began his coaching relationship with Rolf Haikkola. It was quite a coincidence that a small town like Myrskylä had produced two international runners before Viren. One of these two, Perrti Sariomaa, had often been seen by a young Viren training around town. The other international runner was Rolf Haikkola who had run in the 1954 Euros and had a 5,000 PB of 14:14.2. Haikkola had moved from competing to coaching, and it was he who brought Arthur Lydiard to Finland for a two-year stay to improve the lagging Finnish running standard. “Lydiard’s’s ideas of how to bring runners to the best shape at the right time seemed ideal for us with our long winter and short racing season,” he told Kenny Moore. (Best Efforts, p. 97) Viren worked well with Haikkola from the start: “He is the best,” he told Alastair Aitken in 1973. “He is like a father to me. We communicate very well. (More Than Winning, p. 148)

Viren was still intent on building up his mileage, but his legs still sore from the training at BYU. His initial race results were poor. He began with a series of 5,000 races: 14:53.6, 14:33 and 14:10. It wasn’t until August that he began to run well, clocking 14:01 and then a 13:43.0 PB in the Helsinki American Games. In this race he finished second behind Ala-Leppilampi and ahead of Frank Shorter. This was his fastest 5,000 for 1970. He finished off the season with two 10,000s, winning the first in a match against Czechoslovakia (29:15.8 PB), and finishing sixth in the second (29:43.0).

There was no return to Utah in the fall of 1970. Viren attended Police School in Finland and trained hard through the winter. Almost in daily contact with his coach, he gradually increased his mileage. His improved strength was apparent in two May races: he was second behind Seppo Tuominen in the Finnish 10.9K cross-country race and then won a 25K road race in 1:16:24. That same month in his first 5,000 of the season he PBed with a 13:35.2 Finnish record behind Bedford and Korica. This was a great result, but many felt he was peaking too early for the Euros in August. These were to be held in Helsinki, which gave them added importance. So although he continued competing, his times slowed: 13:53.0 (1st), 13:45.2 (1st), 13:42.0 (4th), 13:52.2 (4th), 13:46.6 (2nd). On July 1, in between these 5,000s, he ran a brilliant 10,000, finishing second and only 0.8 of a second behind Korica. In this race he shattered his PB by 58.4 seconds with 28:17.4. Then two weeks before the Euros, he ran a fast 7:54.0 3,000. This was a PB and a Finnish record. For the first of several times, Haikkola had helped Viren to peak at the right time.

1971 Euros

|

|

First time in a major games. Viren leads five European stars in the 1971 5,000: Wadoux, Väätainen, Salgado, Norpoth and Puttemans. |

Despite his encouraging form, Viren finished a lowly 17th in the European 10,000 (28:33.2). But he fared much better in the 5,000. At the bell he was with the leaders on the inside tucked in on the curb behind leader Salgado. But when Wadoux made his move in the last lap, the first six finishers rushed past him. He had no answer to their speed and eased resignedly past the finish line in seventh place. According to Matti Hannus, Viren was pushed as the runners passed the bell and “lost his rhythm completely and almost fell.” (p. 51) Viren told Hannus that he might have won the bronze otherwise. He told quite a different story to Alastair Aitken: “Maybe if I had not fallen, I would have come fifth or sixth.” (More than Winning, p.148) The tactical race showed him that he almost possessed the strength to win a big race, but not the finish. He had run a faster time in his first race of the season, so it seemed likely he could improve on his 13:35.2 PB before the end of the season. The opportunity came eight days after his Euro final in Heinola, Finland. He won his race in 13:29.8, five seconds ahead of Seppo Tuominen. It was a Finnish record.

From August 23 to September 5, he ran a series of seven 5,000s ranging from 13:41 to 13:51.6. He won two of them, including the 5,000 in the international against Sweden. His season wound down with more international matches in which he ran 28:35, 13:55, and 29:08. In October he ran a 20,000 in 1:01:21 in Paris. Overall, it had been a breakthrough season with a good showing in his most important race and some major PB improvements (12.2 for 3,000, 13.2 for 5,000, 58.4 for 10,000). He now needed to work on a winning strategy and the physical qualities needed to carry it out.

Preparation for Munich

Both Viren and his coach believed in altitude training. So, with financial help from the Finnish Association, Viren went to Kenya. He spent three months there at altitude. “All they did was run, eat, sleep, and run some more…. A typical day included a morning run of 1 1/2 hours, then breakfast and a nap, followed by another run in the middle of the day, then more eating and sleeping before an evening run.” (Michael Sandrock, Running with Legends, p. 177) That winter he also spent time in Brazil and Spain, all the time working on his base conditioning.

There was still more conditioning to do once he returned to Finland. The Olympics were still several months away. Viren’s task was to maintain his training load and gradually develop racing speed in his legs. To this end, he trained hard and raced regularly. Of course, the races weren’t serious; they were part of his training.

His competitive season began on May 7 with a 25K road race in Helsinki. After winning it the previous year, he ran two minutes slower, placing third in a mediocre 1:18:27.6 (about 15:40 pace). He then ran third in the Finnish cross-country championships. In the last days of May he ran two 10,000s, three days apart, winning the first in 28:39.0 and placing third in the second in 28:52.0. This looked like preparation for the heats and finals of the Olympic 10,000, which would also be three days apart, although Viren has said that at this time he was only aiming for the 5,000 in Munich.

In June he ran four 5,000s: 14:45.8 (3rd), 13:49.0 (1st), 13:54.2 (1st) and 13:37.0 (2nd). Despite his lack of speed at this stage of the season, Norpoth, Yifter, May and Riesinger were the only ones to beat him in these four races. He ran four more 5,000s in July: 13:51.2 (3rd), 13:44.2 (2nd), 13:33.8 (2) and 13:19.0 (1st). The last of this sequence, run in an international with Spain and Great Britain, was a Finnish record and the third fastest 5,000 of all-time (behind Clarke and Bedford). It was all the more impressive because he had no pacemaker to help him. He won by 14.8 seconds. This July 25 race was 37 days before his first Olympic heat. Had he peaked too early?

Confirmation that he had not yet hit top form came two days later when he shattered his 3,000 pb with 7:43.2, a 10.8-second improvement. There was more to come a week later in the Bislett Games 10,000. After covering the first 5,000 in 14:00, he sped up in the second half of the race (13:52). Winning by over a minute, he broke the Finnish record with 27:52.4. The relative ease with which he ran this race led to his decision to run the 10,00 in Munich as well as the 5,000. Then after winning the Finnish 1,500 title (3:48.5), he broke the world record for Two Miles with 8:14.0. In this race he left a whole bevy of great runners in his wake, giving him more confidence for Munich: Puttemans, Garderud, Stewart, Quax, Bedford and Korica. His margin of victory over second-place Puttemans was 3.2 seconds. In his final pre-Olympic race, the 5,000 in the Finland v Sweden match, he won in 13:32.0. Over a period of 37 days he became one of the Olympic favorites for both the 10,000 and 5,000.

Throughout Viren’s build-up to the Olympics, Haikkola used a special training session to convince him that he was peaking at the right time. Viren did it three times over the three months before Munich, a sequence that was designed to show Viren that he was steadily improving right up to the Games. Each time he ran 20x200 on a track. In these sessions his pulse would be checked after each 200. In June he averaged 30.0 and 198 beats per minute; in July 29.3 and 186; in August 27.2 and 172. (Best Efforts, p. 197) The improvements in these sessions convinced Viren that he could run even faster at Munich. “Trust doesn’t come from personality,” Haikkola told Moore, “it comes from being able to show a runner what he can do.” (Best Efforts, p. 98)

Munich 10,000

|

|

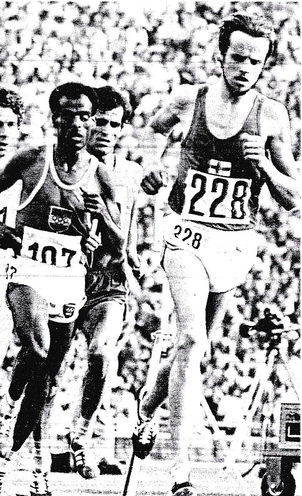

Munich 10,000. Viren leads (left to right) Puttemans, Yifter, and Haro. |

At Munich, he got through the 10,000 heats sensibly, finishing a comfortable fourth in one of three heats. He let Gammoudi sprint away with an unnecessary 58-second last lap. He was certainly more sensible than two of his main rivals, Bedford and Puttemans, who in another heat ran 30 seconds faster than was needed to qualify. The other main qualifiers were Yifter of Ethiopia, who had a good kick, and American Frank Shorter.

Viren’s first Olympic final almost ended in disaster as he tripped and fell at the 4600 mark, losing a good five seconds to the lead group. The race had started predictably with Dave Bedford leading with 60.6 and 64.0 laps. The British star passed 1000 in 2:37, 2,000 in 5:18.8 and 3,000 in 8:06.4. This was 27:01 pace, so not surprisingly Bedford slowed in the next K: 2:49.2.

It was soon after this that Viren and Gammoudi went down. Gammoudi could only run another 600, but Viren was up quickly and appeared unaffected. Normally the trauma of a fall in a race leaves the victim in shock, but Viren was strong enough to get right back into running. By the time the lead group passed 5,000, he was back with them. The time of 13:44 at 5,000 was, according to Athletics Weekly, “the fastest halfway split in history.” (Sept. 16, 1972)

How much had the fall taken out of Viren? Often a fallen runner will regain contact with the field, only to drop back soon after when the shock registers. At 6,000 (16:35.8—2:51.8) he showed he was still okay: he took the lead. At 7,000 (19:27.8—2:52.0) Bedford dropped back. Viren led through 8,000 (22:17.6—2:49.8) before Haro took over. There were now only five runners left in the lead group: Haro, Viren, Shorter, Yifter and Puttemans. One lap later, Yifter moved into the lead, and the quintet passed 9,000 in 25:09.2 (2:51.6). After a very fast start to the race, they were now 10.2 seconds slower than Clarke’s world-record run.

The lead changed a couple of times in the next lap. First Viren and Puttemans went ahead, then Yifter, and then Haro snatched the lead. It was with two laps to go that Viren thought he could win. At 600 out, he began his drive for home. Shorter and then Haro were quickly dropped. Then Yifter lost contact. At the bell Viren led Puttemans by three meters and Yifter by ten. But neither of the two chasers were done, and they pulled back Viren. On the last bend, Puttemans looked like he would catch the Finn. He almost did, but Viren was aware he was in danger and found an extra gear to move away again. 'As we came round to the home straight,' Puttemans said, 'I knew the gold was his.' (Tim Pears, Guardian, July 29, 2007) Viren’s margin of victory was 1.2 seconds; his time was a new world record by one second: 27:38.4. He had run the last 1,000 in 2:29.2, the last 800 in 1:56.4 and the last lap in 56.4. And all this after a bad fall. Just as importantly, he had found a tactic that worked: a long drawn-out effort from 600 out.

Munich 5,000

|

|

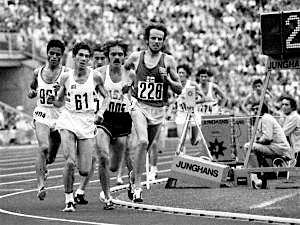

Munich 5,000. Just under two laps to go. Viren forces the pace. Puttemans (61), Prefontaine (on inside) and Gammoudi follow. |

So it was on to Viren’s best event, the 5,000. Arguably, he had even tougher competition to face. Puttemans, Prefontaine and Stewart were all fast and strong enough to match Viren’s 10,000 tactic. Indeed, both Prefontaine and Stewart had told the press that they could run the last mile in under 4:00 if necessary. And then there was Bedford, whose 13:17.2 run in the British AAA Championships was the fastest of the year—and second fastest all-time. Would he be able to run away from the field? One break for Viren was that the speedy Yifter was not in the final as he had missed his heat.

The final was expected to be fast, as most of the favored runners, like Viren, Prefontaine and Puttemans preferred a fast pace. But it was slow: 2:46.3, 2:46.3 and 2:47.6. The leaders passed 3,000 in 8:20.2, which was 13:53 pace. Viren started off at the back for the first five minutes of the race. Then he moved up to the front, but only 45 seconds later Bedford took over. Viren, still hugging the curb, dropped back. There was a lot of jostling at the front. Viren’s main rivals (Puttemans, Stewart, Prefontaine, Gammoudi) were often in lane 2 on the bends. Viren was in seventh at 3,000. Then passing Prefontaine on the inside, he was up to equal third with little effort.

|

|

Munich 5,000. Just over 300 to go. Both Gammoudi and Prefontaine are about to overtake Viren. |

No one led for very long until Prefontaine shook up the race with four laps to go. Viren, on the inside was quickly passed by most of the field. He took time to react and gradually accelerating, moved up to Prefontaine. In this catch-up mode he had to run in lane 2 round one bend. Prefontaine reeled off laps of 63and 61 with Viren right behind. Prefontaine’s pace broke up the field with 900 go. There were five still in contention: Prefontaine, Viren, Stewart, Gammoudi and Puttemans. Just before two laps to go, Viren took the lead, but on the back straight Prefontaine made a big effort from fourth place and passed Viren. He really pushed he pace round the bend, and Viren had to find another gear to stay with him. Just before the bell, Viren moved into the lead despite Prefontaine’s 59 lap. Prefontaine’s surge in the previous 200 had dropped the other three. Only Gammoudi could react at the bell and catch the two leaders.

Along back straight both Prefontaine and Gammoudi challenged Viren. Both got by with Gammoudi in the lead. Viren, seemingly unperturbed, hugged the curb round the final curve and got by Prefontaine on the inside for the second time in the race. Just past the crown of the last bend, when Prefontaine came to his shoulder, Viren took off and quickly passed Gammoudi. Within 5 seconds he was in front and on curb! And he quickly built up an unbeatable lead to win the gold medal. 1. Viren 13:26.4; 2. Gammoudi 13:27.4; 3. Stewart 13:27.6; 4. Prefontaine 13:28.4

Later Viren revealed that he been forced to change his tactics: “I had planned I would lead after 3,000; then I would run fast. But all the other runners were around me, so I did not have the chance to lead, and I had to wait. So it was with three laps left that I started to pass the other runners and make for the lead position. “ (Aitken, p.150)

How much farther than 5,000 did Viren’s main rivals run in this race? A lap run in lane 2 is 7.67. longer than a lap run in lane 1. In this 5,000 final, Viren ran close to the curb on the bends throughout, except on lap 9 to catch a surging Prefontaine. Thus in the whole race he ran only one bend in lane 2. All his other overtaking was done on the straights. This means that Viren probably ran as little as 10m extra in the whole race. Prefontaine, who was probably the most extravagant of the main contenders, never ran a bend on the curb until 8.5 laps had been run. I calculate that he ran 7 bends on the curb, 10 bends on the outside of lane 1 (with someone inside him) and 8 bends in lane 2. That would mean he ran 99.7 meters extra. Thus, factoring in Viren’s extra 10m, Prefontaine ran 89.7 meters more than Viren—a very significant amount. Thus it’s fair to conclude that one of Viren’s most effective racing tactics was to run on the curb whenever possible. Brendan Foster showed awareness of this aspect of racing when he talked about this race: “[Viren] ran 500m for the last 500; we ran 508m or something like that in the second lane coming round the bend.” (Athletics Weekly, Oct. 23, 1976)

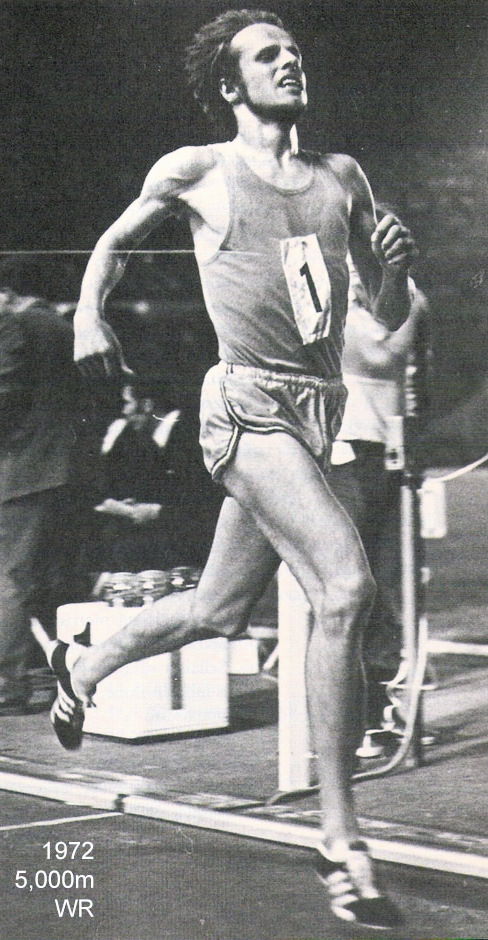

World Record

|

|

13:16.4: World record for 5,000 |

Four days later, the now famous Viren lined up beside Dave Bedford for a hastily arranged 5,000 in Helsinki. In front of an enthusiastic Finnish crowd of 40,000, Bedford as usual set off at a fast pace, covering the first K in 2:36.6. Bedford maintained a reasonably fast pace past 3,000 (8:00.3) to 3,800, when Viren took the lead. He soon opened up a gap, covering the fourth 1,000 in 2:42.3. Despite the wet and windy conditions, a world record was now possible. He needed to run the last 1,000 in under 2:34. And with 2:33.8 he just beat Clarke’s world record with 13:16.4. Far behind, Bedford (13:30.0) finished second ahead of Vaaitanen (13:35.4) Viren, though primarily a racer, had now joined the elite club of runners to hold both the 5,000 and 10,000 world records. His 1972 season with two Olympic golds and three world records ended with an inevitable anticlimax of half a dozen low-key races.

Dealing with Success: “So Much Hullabaloo”

His life changed for ever, Viren now had to deal with his new status as a celebrity. He was unable to “disappear” over the winter and build up his mileage. On visiting Viren in December Hakan Nordqvist reported that “Lasse’s days are filled with various appearances and social obligations.” Viren’s father was concerned about all the attention his son was receiving: “He needs adequate time and sleep to get in shape for next season.” (Track & Field News, 1973 ) Matti Hannus reported that after Munich Viren traveled Finland for several months, first racing and then “giving speeches and lectures, visiting schools, factories, old people’s homes.” (Athletics Weekly, Oct 23, 1976). In early 1973 he also traveled to Brazil, USA, Japan and Portugal.

His 1973 season was understandably much less successful. Without the training base of previous years, it was impossible to match his 1972 performances. He started well enough with a 28:17.8 10,000 in May and a 13:28 at the end of June, placing fifth in the Helsinki Games. He was fourth again a month later in the Helsinki July Games (29:17.4). In the Euro Cup Final he was only fifth in the 5,000 (14:18.73), 23 seconds behind the winner Brendan Foster. Booed by the Scottish crowd, he said he hadn’t been interested in running in this race. This incident illustrates how mentally strong he was in deciding what he wanted to do. There must have been a lot of pressure to put out for his country. It wasn’t that he was in bad form, because six days later he won the 10,000 in an international race against the USSR and East Germany (28:48:07). In 1973 he was ranked 15th and 8th in the world for 5,000 and 10,000—very respectable but not up to his 1972 level.

Back to the Grind

The 1974 Euros was an important meet for Viren, so he wasn’t going to neglect his winter conditioning again. He knuckled down to his training and even tried some indoor competition in February. His second place in the May Finnish 15K cross-country championships confirmed his good basic condition, as did two early-season 10,000s in the 28:50s. But then Viren suffered a bizarre accident when he jumped up to answer the phone and struck his thigh on a table. He had to stop running and wasn’t able to compete for a month—the whole of July. A second place in the Paavo Nurmi Games in 13:30.6 and then a 28:30.0 victory in the annual match against Sweden two weeks later gave hope that the thigh injury would not affect his Euro competition. But he was not 100%, and it showed. “I was completely out of shape,” he claimed. “Never in my life have I been so tired after a race…. I was thinking of winning until a lap to go when my hamstring tightened again and I had to lose contact.” (Athletics Weekly, October 23, 1976) He finished seventh with 28:29.3.

|

Viren did better in the 5,000. The race was dominated by UK runner Brendan Foster, who took the lead from the gun. Foster ran steady kilometer times, but did surge. After 2:39.2 and 2:41.0, Foster surged near the end of the next K and only Viren could match him. The two passed 3,000 in 8:01.2 with the pack, led by Kuschmann, 20m back (8:04.4). But soon Foster, with laps of 60..2 and 62.8, had Viren lagging by 30m. “I tried to shadow Brendan Foster when he began his strong drive with five laps to go,” Viren recalled, “but I soon realized that it was futile. So I settled down to fight for the other medals…. I was not happy, but in the circumstances I really should have been.” (Athletics Weekly, October 23, 1976) While Foster powered alone to victory, Viren was caught by the pack before the bell and had to fight it out over the last lap. Kuschmann of East Germany earned the silver with a 56.0 last lap, while Viren was close behind, passing Jos Hermans in the straight for the bronze and a season’s PB of 13:24.57.

Following the Euros he showed good form, but still not quite the form of 1972. His summer injury was still a problem. He won the Finnnair Games 5,000 in 13:26.0 from Garderud, Prefontaine and Malinowski, and he won the 10,000 in a match in Sochi against the USSR (28:22.6, a season’s best).

Surgery

As he entered the 1974-5 winter, Viren was still having problems with his thigh injury. Finally he had it operated on early in 1975. This put a big hole in his conditioning. Fortunately there were no major races in 1975, so he took his time getting back to full training. His first race of the year was on May 11—the Finnish 5K cross-country nationals, where he finished second to Kantanen. But in his first track race on May 20 he was only 8th in a 10,000 (29:22.6). In the Helsinki Games 5,000 at the end of May he could only finish 7th (13:51.2). His times gradually improved--28:43.2, 13:42.39, 28:47.8, 13:34.51—but he wasn’t winning his races. Still, he continued competing into October and accumulated 32 track races for the 1975 season, mainly in Finland (22). Viren has explained why he competed so often when he wasn’t in top condition: “It is absolutely necessary to stay in touch. Running to maintain the spirit. Otherwise it would be so much harder to come back again.” (Hakan Nordqvist, Track & Field News, October, 1977) Viren also explained the reasons for this mediocre 1975 season: “I had all kinds of illnesses and slight injuries, which kept me down. But I was not worried, for I was already thinking a year ahead, and there was no reason why I shouldn’t succeed.” (Athletics Weekly, October 23, 1976) His best times for 1975 were 3:46.4, 7:54.2, 13:34.6, and 28:11.4. In world rankings for 1975 he was 29th in the 5,000 and 31st in the 10,000.

Conditioning for Montreal

Viren spent a lot of the next winter at altitude, first in Colombia and later in Kenya. Now over his injury, he was able to put in the mileage he felt he needed. In short, his winter conditioning over 1975-1976 was close to perfect. When he ran the Helsinki 25K road race in April, he was 4:06 faster than in 1972.

He began with a few low-key races. Then in early June he contracted a bad sinus infection. For two weeks he was unable to train properly, and in his first international race he ran a below-par 13:59.2 for 11th place. But by the end of June he had recovered. In the Helsinki World Games he won the 10,000 in the impressive time of 27:42.95. The was only four seconds slower that his world-record run in Munich and just 12 seconds slower that Bedford’s world record (27:30.8). He was back, and there was only a month before the Montreal Olympics began.

In that period he raced seven times, mainly over 1,500, where he clocked a PB 3:41.8. His best run was a 13:24.78 victory in the Finnish championships. As part of his final preparation he also ran some training sessions at the time of day he would be racing in Montreal. That meant going out at midnight Finnish time. Thus Viren flew to Montreal with a feeling that his preparation was close to perfect.

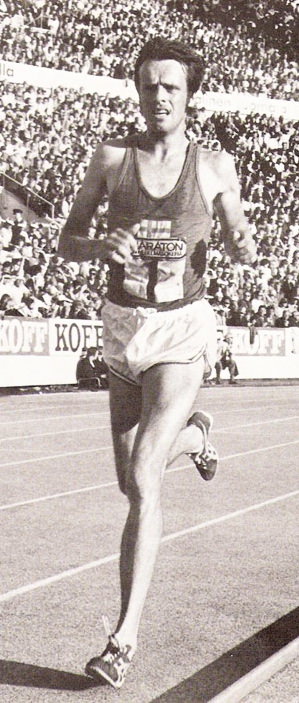

Montreal 10,000

|

|

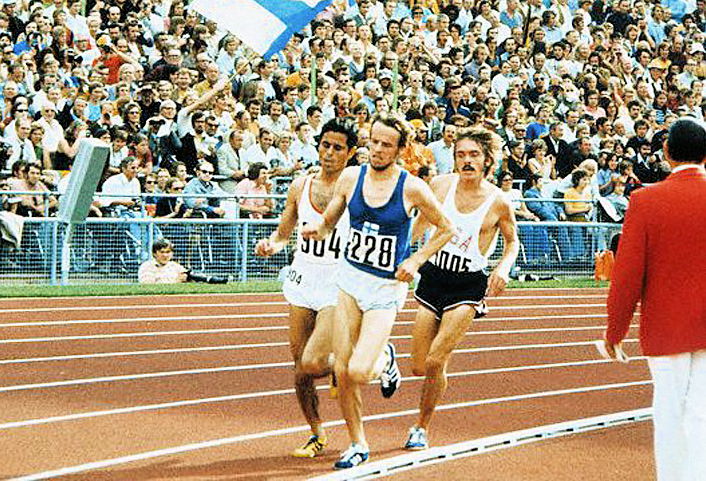

Montreal 10,000. Viren has just passed Lopes of Portugal. |

As Viren lined up for the Olympic 10,000 final, he must have thought good fortune was on his side. As Robert Parienté put it, Viren had several breaks before the final: “Puttemans below form, Foster unwell, Quax victim of a stomach virus, the Africans boycotting, the situation was considerably uncertain.” (La fabuleuse histoire de l’athlétisme, p. 450) Viren came to Montreal with the best time of the year: 2.8 faster than Carlos Lopes and 11 seconds faster than Brendan Foster. These two were to be his main contenders in this final.

The race began slowly and didn’t pick up until Lopes took over after eight laps. They had gone through 3,000 in 8:33.4. Lopes was still ahead at the halfway point (14:08.9). His pace gradually thinned out the field, so that by 7,000 (19:36.3), only three runners were in contention: Lopes, Viren and Foster. After another 1,000 Foster began to fall back; it was a two-man race. Lopes, always leading, injected a 2:42 penultimate kilometer, but it had no effect on Viren. It was just a matter of when Viren would go. He, as usual, chose a straight to make his move—at 450 to go. Lopes offered no resistance. Viren look incredibly comfortable as he covered the last lap in 61.3 to clock a fast 27:40.4 and gained a 4.8-scond margin over Lopes. He had run the last 3,000 in 8:03.7 and the second 5,000 in 13:31.5. It was clearly his easiest gold-medal win.

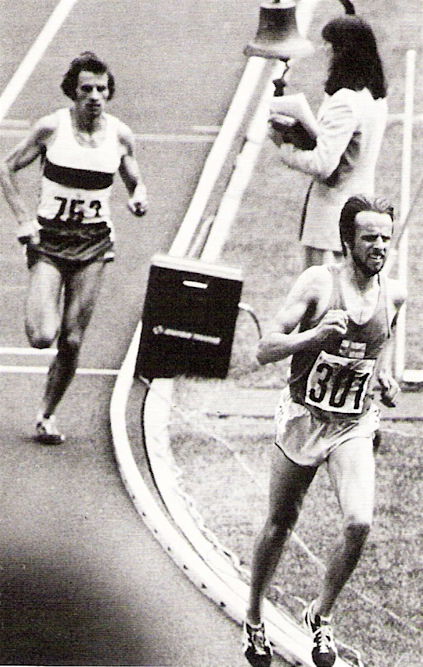

Montreal 5,000

|

|

Montreal 5,000. Mid-race. Viren has moved into the lead to avoid jostling in the pack. |

Two days later he qualified for the 5,000 final with 13:33:4, a tad slower than his second 5,000 split in the 10,000. He was now ready for the race of his life. The two New Zealanders, Quax and Dixon, looked in great form and both had good finishes. Ian Stewart was back again. Brendan Foster, third in the 10,000, had fully recovered from his illness. And the Russians Sellik and Kuznyetsov had both recently run sub-13:20. Clearly Viren would have to negate the finishing power of Dixon and Quax. He would have to use a lot of tactical savvy with so many good runners out for his blood.

But Viren nearly didn’t make it to the 5,000 start line. Following his 10,000 win, he had run a victory lap and waved his Asics spikes to the crowd. The International Olympic Committee, still promoting the amateur values of the Olympic movement, suspended Viren from the 5,000 for showing off the Asics logo to the spectators. Viren claimed he had taken off his shoes because of a blister, and he successfully appealed against the suspension. All this must have been quite a distraction; fortunately Viren showed no ill-effects from the incident.

The two Soviet runners led from the start, but soon Foster was in front, showing his intention to make the race at least reasonably fast. He took the field through 1,000 in 2:41.5. The bunched field made it hard for Viren to maintain a good position on the inside, and after Foster had led through 2,000 in 5:26.6, He ran wide and up into the lead. “The group was so restless,” he explained, “that it was better for me to lead than to run in the pack.” (Track & Field News, Sept., 1976)) Viren didn’t really push the pace, and there was a lot of jostling for position behind him. Eventually Viren, always on the inside, fell back into the pack. A slow third K led to a time of 8:16.3 at 3,000. Hildebrand finally injected some pace at the front, and the field covered the next K in 2:39.2. After a lot more jostling and lead changes, Viren took over with 1k to go. Foster was quickly on his shoulder. After another lap Viren’s acceleration began to thin out the field.

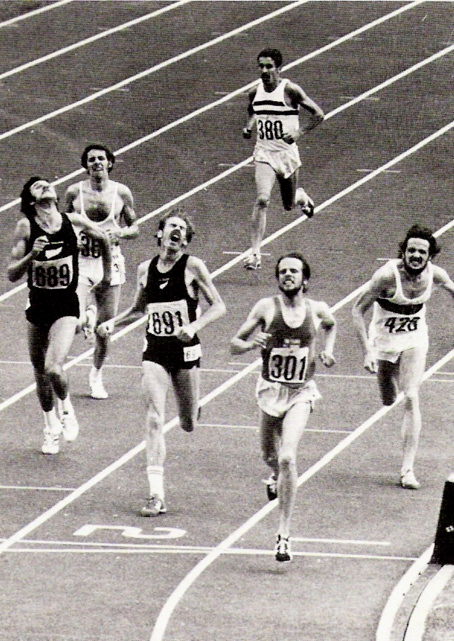

|

|

The finish of the Montreal 5,000. Viren holds his form better than Quax (891), Hildebrand (426), Dixon (889), and Foster. Stewart is sixth. |

At the bell Viren was still in front with Stewart on his shoulder. As they entered the back straight, Stewart made his move, but Viren easily held him off. At the same time, Hildenbrand was storming toward the front on the outside, and Dixon was moving up. On the final bend, Viren had to work hard to hold the lead from Dixon. He still led coming into the straight, but a desperately sprinting Quax moved up to him in lane 2 and drew a fraction ahead. However, at this stage all his challengers were spent, and Viren kept his form and tempo to hold them all off—Quax, Hildebrand, Dixon and Foster. It was a superb race, and Viren had won by using his tactical skills to perfection. He had covered the last 300 in 40.8 and the last 400 in 54.8. The last lap was not that fast; it was the speed of the last 2K that did the damage to Viren’s opponents—5:08 for the last 2,000, 2:29.0 for the last 1,000 and 1:57.5 for the last 800. He thus became the first runner to complete the 5,000/10,000 double in two consecutive Olympics.

Later he was asked by one of his main challengers, Brendan Foster, “Weren’t you nervous with all those great athletes queuing up on your shoulder in the last lap?” His answer gives a good insight into Viren’s mental attitude in big races: “No, I never thought about it. I just had to get to the line first. My coach said, ‘Get to the front with 600 meters left, and stay there.’ So I did.” (Foster and Cliff Temple, Brendan Foster, p. 166)

Olympic Marathon

No doubt thinking of Zatopek’s Olympic treble in 1952, Viren lined up for the Marathon the next day. He must have been the most inexperienced marathoner in the field. And also the tiredest and the least prepared. Having won the 10,000 the day before, he had not been able to get to bed early. In fact, the race started just 18 hours after his 5,000 final. His plan was simple: to key on to Frank Shorter, the reigning Olympic Marathon champion. He knew Shorter well and had trained with him in Colorado.

This plan worked well for him, but he had not been able to prepare himself properly for a Marathon and when the crucial time of the race arrived, he predictably hit the wall—though not at all catastrophically. This was why Shorter did not see him as a threat: “His energy reserves—that is the foodstuffs that fuel the muscles—would have been significantly depleted during the week. He would also have been dehydrated.” (Olympic Gold, p. 108)

Bill Rodgers pushed the early pace, but Viren still focused on Shorter. After the lead group passed 15K in 46:00, Shorter began to assert his presence with several bursts, whittling down the lead group from 12 to 8. Viren stuck close and was still with Shorter at 25K (1:16:35). Soon after this Shorter and the eventual winner Cierpinski broke away from the lead group. By 30K Viren was 28 seconds back in 5th. Viren held his own, and at 35K he was running with Lismont and Drayton in third. Ultimately he couldn’t stay with Lismont and was passed by Kardong over the last 7K. But his endurance kept him going, and he finished a very creditable 5th in 2:13:10.8. It was a remarkable performance so soon after his 5,000 final. Zatopek, who managed to win the Marathon after winning the 10,000 and 5,000 in the 1952 Olympics, had three days to recover from the 5,000.

The rest of Viren’s 1976 season was an anticlimax . He was persuaded to run a Two Miles in Philadelphia four days after his Marathon, and he ran quite well considering: 3rd in 8:21.47 behind Quax. He raced jetlagged in Edinburgh two days later, finishing 11th in a Two Miles (8:35.34). Back home in Finland he first ran a 5,000 with a head cold, finishing 7th in 13:42.10. Another nine races in Finland produced two sub-13:40 5,000s. He had three wins in local races. Perhaps his best run was a 10,000 in the match against Sweden, where he finished second to team-mate Vainio in 28:46.21.

The Late 1970s

With his four Olympic gold medals, Viren could have retired at this point. In fact he did consider retirement in 1977 when injuries were plaguing him. But his love of running was still alive. Moscow in 1980 was in his sights. However, his winter conditioning did not start on schedule. In mid-October, a few days after finishing second in a Half-Marathon (1:05:17)in his home town, he injured his ankle while hunting. On December 14 it was operated on. His leg was in a cast for a month, and it was another month before he could begin running.

Viren didn’t race until April 24, 1977—a 25K road run in 1:24.42 (14th)—10:21 slower than 1976. He was only 21st in the Finnish 5K cross-country championships. His times in June indicate how unfit he was: 14:03.56 (10th), 3:55.2 (5th) 8:26.2 (4th), 14:39.0 (11th), 8:11.6 (13th), 8:17.0 (3). After a trip to the USA for the Peachtree (8th in 30:37), he returned to domestic competition on July 17. At the Finnish Championships at the end of the month he ran a poor 18th in the 5,000 (14:27.9) and 9th in the 10,000 (28:29.16).

Gradually getting fitter, he had 11 more track races that season, with bests of 8:02.2, 13:35.77, and 28:39.8. His best race of the year was again in the annual match against Sweden, where he ran his season’s pb of 13:35.77 for second place. Then in October he took to road racing winning a Half-Marathon in his home town in a fast 1:02.23 and then placing 17th in the New York Marathon with 2:19:31. In December he went to Japan for the Fukuoka Marathon (15th in 2:20:40).

In the early part of 1978 he followed many European runners and went Down Under for warm weather conditioning in New Zealand and Australia. From January 8 to 28 he “raced” six times, ambling through a 3,000 in 8:27.0 for 13th place in Brisbane and through a 5,000 in 14:29.0 for 11th place. His only respectable time was a 13:58.7 in Christchurch, where he was still back in 9th place. Still, he was really focusing on conditioning for the 1978 Euros. And by May he was running well, winning the Finnish 5K cross-country title and then posting a fast time of 1:07:40 for the Helsinki 25K road race—he was 1:19 faster in 1976 when he was in great shape.

But once he started his track racing, a respectable 7:57.24 in the 3,000 at the Helsinki May Games, he developed a knee problem. Clearly his years of high mileage were now increasingly taking their toll. Undaunted, he still had his sights on the Euros later in the summer, so he continued racing—seven more times in June. A 13:33.76 clocking for fourth in the Helsinki Games 5,000 was somewhat encouraging. At the end of June he place only eighth in the 10,000 (28:11.8) in the Helsinki World Games, 14.6 seconds behind the winner Craig Virgin. Things looked bad when he could finish only fourth in the Finnish Championships 5,000. The next day he dropped out of the 10,000 and announced he would not be competing in the Euros. He did however run for his country in the annual match against Sweden (4th in 14:09.72). Season over.

Was Viren in decline? Should he have retired after Montreal? It certainly looked like he was “past it” in the early part of the 1979 season. Three 5,000s in the 13:50s and three 3,000s averaging 8:09 in June didn’t look promising. But a 28:39.45 in a match against France and a 13:46.2 for 5,000 suggested he might be back. In the Finnish championships he was third in the 5,000 (13:47.27) and second in the 10,000 (28:24.16). And although he got his times down a little further (28:04:09 and 13:32.2), he was being left behind in the big races: 12th in the Ivo Van Damme meet and 20th in the IAC/Coca Cola meeting. For 1979 he didn’t make the top 30 in the world rankings for 5,000 and 10.000.

Moscow Preparation

Nonetheless, the Moscow Olympics were still on his dance card. He clearly felt that he had a chance as long as he kept injuries at bay. Viren has said that he trained too much like a marathon runner in the winter of 1979-80. And he was able to put in many of the miles at altitude. As late as April he was training in the mountains of Colorado. Still in the USA in May, he ran a respectable 15K, finishing second to American Lindsey in 44:05. Back in Finland five days later. he finished third in the Finnish 15K cross-country championship behind Maaninka and Vanio. In the next two months he raced intermittently, with his best times only 7:57.86 and 13:55.05. Then three weeks before the Finnish Nationals, he injured his thigh. He managed to recover for the Nationals to place third behind Vainio and Maaninka in the 5,000 (13:45.07). Five days later in the Helsinki World Games he ran much better, finishing the 10,000 in fourth place with 28:10.95. A good run but not quite Olympic-medal class.

Third Olympics

Viren didn’t feature as one of the favorites for the Moscow Olympic 10,000 (he opted for just one event this time). There were however 65 boycotting countries, so he was expected to make the final. But conditions for the 10,000 heats were very warm, not ideal for Nordic runners. Viren dropped back from the lead group with three laps to go, and it looked like he would not qualify for the final. However, John Treacy, who was well ahead of him, collapsed from the heat on the last bend and Viren squeaked into the final in fourth place. As it turned out later, he would have qualified as one of the fastest losers.

The weather had cooled noticeably for the final (65f/17c). This suited Viren much better, and he was a different runner this time. As the race developed into a five-man contest between two Finns, Viren and Maaninka, and three Ethiopians, Yifter, Kedir and Kotu), Viren was very much a participant at the front. Unlike his tactics in previous Olympic finals, when he stayed on the inside near the front until he made his drive for home, he now seemed to want to stay on the leader’s shoulder. This time it was Yifter who ran on the inside behind the leaders; this time it was Yifter, with the help of his two compatriots, who was in control of the race. Viren’s running seemed anxious, not as smooth as usual.

On the penultimate lap he took the lead round the first bend as if he were starting his patented drive for the tape. For the first time Yifter reacted quickly to move to second. But then with 550 to go, Kedir was back in front. Viren again moved up to Kedir’s shoulder, and the two passed thee bell side by side. With just over 300 to go Yifter exploded into the lead and immediately opened a significant gap. Viren acknowledged defeat at this point; he made no response at all as Maaninka and the other two Ethiopians rushed past him. As Yifter reeled off a 54.7 last lap, Viren coasted home in fifth, almost eight seconds behind.

To win, Viren would have needed to run much faster earlier in the race to negate Yifter’s amazing sprint finish. His attempt to go with two laps to go was totally ineffective; the strength he showed in Munich and Montreal was no longer there. Still he had shown again how well he was able to rise to the occasion. His time was his best since his win in Montreal four years earlier. Yet again he had run negative splits: 14:03 and 13:47 for 27:50.46. Understandably, Viren called this “one of my best races.” (Luhtala, p. 323)

Viren also entered the Marathon in Moscow. This time he wasn’t able to finish, dropping out before the 30K mark, a victim of the stomach virus that was sweeping through the Olympic village. After Moscow he ran 12 races without one victory. After competing in the major meets, ISTAF (8th), Cologne (9th), Ivo Van Damme (DNF), Weltklasse (11th), he finished his season with two 10,000s for Finland against Sweden and Italy. His fastest 5,000 (13:30.88) was in the Zurich Weltklasse.

Winding Down

Officially retiring n 1981, he nevertheless kept in reasonable shape. The 1984 Olympic Marathon was still in the back of his mind. Thus to test his general condition, he ran the 1983 New York City Marathon in November, finishing 103rd in 2:23:54. In 1984 he started in the Stockholm Marathon in June but didn’t finish. That must have been his last thought of the summer Olympics.

Amazingly he was still running quite seriously in 1988 at the age of 38. He ran the Los Angeles Marathon in June, finishing 59th in 2:27:31. Was he still thinking of the Seoul Olympics? Not really! He did run one more Marathon that year: a 3:25:18 in Honolulu for 642nd place. In that race 641 runners confirmed that Viren was now a “fun” runner and no longer an Olympic runner. His main focus became making a living. He did this first by working in a bank, then working for his family trucking business and then as a politician. He sat for several years in the Finnish Parliament (1999-2007, 2010-2011) as a member of the National Coalition Party.

Conclusions

Many people have attested to Viren’s dedication. He certainly needed a lot of dedication to train consistently over long periods. Viren’s mother confirmed that he was special from an early age: “Everything he wanted to do he wanted to do perfectly.” (Moore, p.100) This perfection comes out in a comment Viren made about his 6am runs: “I was so punctual that my neighbour was able to check his clock by my runs.” (Luhtala, 320) Dedication and perfection require inner strength, and Viren had this in spades. Brendan Foster, in his autobiography, notes Viren’s “tremendous strength of character.” (p. 165)

His ability to train so hard and so consistently was made a little easier by his love of running. “I have always enjoyed running, [it was] never a sacrifice to train,” he once wrote, adding “I enjoyed training hard.” (Luhtala, p. 318)

He was blessed with intelligence and athletic talent, but denies he was lucky to have such talents: “Of course you need good luck, but you must also work hard. I’m no more lucky than any other runner. The main thing is to do hard work and never lose hope.” (Moore, p. 96) It could be argued that he was lucky, with the high mileage he did over long periods, that he didn’t have more injuries, but he used his intelligence to avoid injury by choosing his surfaces carefully and by regular massage therapy.

On the other hand, he was definitely lucky to team up with his coach Rolf Haikkola. Viren was always in full agreement with his coach’s approach to conditioning, and he benefited greatly from Haikkola’s ability to get him to a peak at the right time. Viren once said, “Working up to a peak every year is mentally—if not always physically—very tough.” (Nordqvist, 1977) So he needed Haikkola’s guidance and support in this crucial aspect of competition.

So how did Viren do it? How did he win those four Olympic golds? Some believe he must have blood-doped, a technique that was new at the time. Viren has always denied he blood-doped: “I say every time, no. I didn’t take blood.” (www.jamesraia.com) Blood-doping in fact does exactly the same as altitude training, Viren’s main conditioning practice. So while some believe in the blood-doping theory, others, like Brendan Foster, Frank Shorter and Arthur Lydiard, believe he was just a great, strong-willed athlete who trained hard and raced intelligently. And this is what this profile has tried to show.

---

Training

|

|

Winter training on Finnish roads. Note the heart monitor being shown to Viren. |

Viren’s training methods evolved over the first few years of his career and were finally established soon after he chose Rolf Haikkola as his coach. These methods were first developed through his contact with other runners and through early connections with the Finnish athletic authorities. Finnish coaches were strongly influenced by the presence in Finland from 1967-9 of Arthur Lydiard, the New Zealand coach who advocated high-mileage conditioning for all types of middle-distance runners. Viren’s personality was also suited to Percy Cerutty’s conditioning ideas that advocated running in nature and away from the track. Thus from early on he was running in the forests and practicing Scandinavian fartlek. In Finland there was also interest in new techniques, of which altitude training was the most dominant. Viren was sent to Fort Romeu as early as 1970 to try altitude training, and it became one of the main features of his training.

Haikkola was a Lydiard follower and ensured that Viren kept his mileage high, eventually sometimes up to 200K weekly, throughout the conditioning period. High mileage at steady speeds was the foundation of Viren’s program. Another influence, though a lesser one, was Mihaly Igloi, who advocated interval training over short distances. Viren sometimes used sessions of alternating 50m sprints and 50m jogs over 5,000. These were summer sessions. Because Viren disliked interval training on running tracks, the conditioning period had Viren working on his speed with Fartlek and with power-running uphill. Even in the summer he preferred to do his fast running away from the track, except when he used races as time-trials, which he often did.

From his early experiences of altitude, especially his long-term stay in Utah, Viren used altitude conditioning regularly throughout his career. As Tanser has said, Viren became “something of a pioneer in altitude training.” (Toby Tanser, Running Times, Sept. 1, 2004) Under Haikkola, Viren worked hard to develop his aerobic capacity until he had “an enormous capacity for transporting oxygen.” (Moore, p. 101) Thus he had a resting pulse of 32 and a hemoglobin count of 15.4-15.6. This is close to the optimum level and is too high for any benefit from blood-doping.

Haikkola and Viren were highly adept at peaking. Of course, reducing the training load was part of the peaking process, but Viren still trained twice daily in the competitive season. For sharpening, Viren would use Igloi-type sessions and also races. He was unusual in this respect because he didn’t mind finishing low down in races that weren’t important to him. Frequent racing without pressure enabled him to develop tactics and to get comfortable with the rhythm of racing speed. A special method for peaking called “emptying” was used for major races. This was done five days before and required a flat-out effort on the track, usually over 5,000. Viren’s name is almost synonymous with peaking. And Haikkola must take a lot of the credit for Viren’s success in Olympic races, especially from a psychological perspective.

5 Comments