DAVID MOORCROFT PROFILE

born 1953

|

|

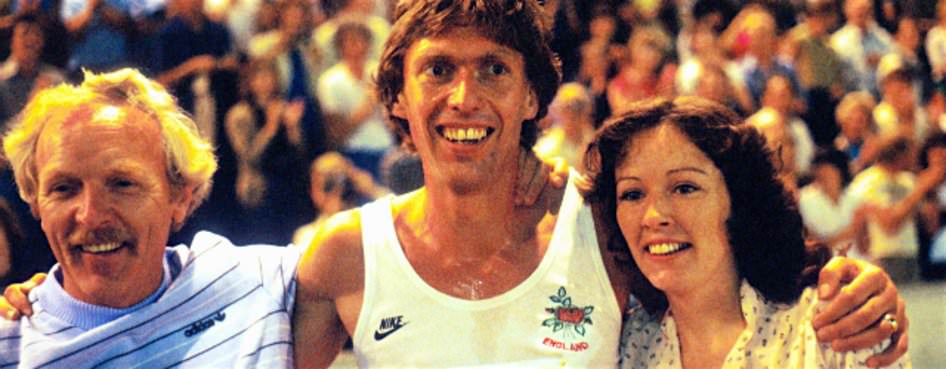

David Moorcroft with his wife Linda and his coach John Anderson |

His brilliant and stunning 5,000 world record in 1982, which knocked 5.79 seconds off the previous mark, has obscured David Moorcroft’s fine competitive record in his long running career. True the English runner did not achieve Olympic glory, but he did win two Commonwealth golds (1978, 1,5000 and 1982 5,000), a European bronze and a European Cup title (5,000 in 1982). In the years 1975 to 1982 he was rarely beaten when he was in top shape.

Although a three-time Olympian, he never achieved Olympic glory. In his first Games he was an up-and-comer and was pleased to make the 1,500 final. Indeed he ran well and was only 1.77 seconds behind the winner in seventh place. In 1980 illness prevented him getting into the final of the 5,000. Finally in LA he was the favorite, made the 5,000 final, but then hobbled in last with a pelvic injury.

So Moorcroft will be remembered mainly for his 13:00.41 world record. Thirty-two years later in 2014, only six runners beat his time, and all of them were from Africa. He did not achieve the celebrity status of his contemporaries Coe and Ovett, but within the running community he has always been respected as one of the great runners who made the most of his natural talents, who persevered for 18 years to reach his full potential, and who competed intensely.

-----

He was only eleven years old when his supportive father enrolled him with the local running club, Coventry Godiva, which was one of the top clubs in England. The club, through coaches Reg Payne and Mick Crossfield, provided him with all support he needed. He found more early success with cross-country and represented his county Warwickshire from the age of 13. Not endowed with natural speed, he was never able to qualify for the county team on the track, even though at 16 he ran 4:11.0 at 15 and 4:04.7 for 1,500. As a schoolboy, David Moorcroft showed little talent as an athlete or a student. He enjoyed running but he was not always successful. In fact on one occasion at age 12, he was last in a cross-country race: “I thought the earth had crumbled beneath me.” (Running Commentary, p. 14) He was not even the best runner at his school. While he was above average as a runner, he was only average academically and failed all his O-levels.

Meeting up with John Anderson

Finishing school without any O Levels, he looked likely to take up an apprenticeship in the car industry. This is where Scottish coach John Anderson comes into the picture. Anderson was based in Scotland, but he was coaching Coventry Godiva runner Sheila Carey, who was to place fourth in the 1968 Olympic 800. Moorcroft, through his club coach, started to get advice from Anderson. The Scottish coach recalls: “All the initial advice and work was done by telephone and letter to his father, who in turn ensured that David worked through the programmes and at the same time provided me with feedback on David’s progress.” (John Anderson, “Breaking the Thirteen-Minute Barrier,” 12th Congress of the European Coaches’ Association on Distance Running, 1983)

Later, when the 1970 Commonwealth Games were held in Edinburgh, Moorcroft went up to Scotland to stay with Anderson. Thus began one of the great coaching partnerships. Moorcroft matured quickly under the Scot’s influence: “I began to realize that I would not be content always to gravitate towards the average. … I had to conquer my own insecurity and a reluctance to become someone different…. I began to put together the bones of being an independent person.” (RC, pp. 23-4)

Immediately after his visit with Anderson, Moorcroft had a breakthrough on the track, improving ten seconds over his previous year’s time in the AAA Junior Championships. Still, his 3:55.7 (after a 3:57.8 heat) earned him only sixth place.

As well as becoming more serious about his running, Moorcroft also decided to go to college for two years (1970-1972) to get his O-levels. Soon after he met a fellow college student, Linda, who was to become his wife. They both studied hard with a long-term aim of qualifying as teachers.

Getting a Reputation

|

|

Winning his first national title, the 1971 AAA Junior 1,500. |

Contact with Anderson at this stage was still done by phone, as Anderson was still in Edinburgh. But there’s little doubt that his influence was quickly taking effect. In the new year, Moorcroft placed seventh in the National Youths Cross-Country, won the National Junior 1,500 title with 3:55.8, and then in the AAA Road Relay ran the fastest short leg for his club. With his reputation rising he was invited to compete in two outdoor 1,500s as a guest. He won the first in 3:48.6 and finished second to Ian McCafferty in the second with 3:48.5. A few days later he was selected to run for the AAA against Loughborough College. He ran second to John Kirkbride with a new PB of 3:46.1, his best time for 1971. His best race of the season was the AAA Junior 1,500, which he won in 3:51.9. Within one year, Moorcroft had moved from “promising” to “really promising.”

His rapid improvement slowed in 1972. True, he did improve over 1,500 to 3:45.7 and over the Mile to 4:03.3, but he had some poor races, especially in the prestigious Emsley Carr Mile, where he finished last in 4:18.5. In the AAA Championships he failed to reach the final. Perhaps his completion of his O-level studies and his application to Loughborough for teacher’s training took some of his attention away from the track.

Getting Serious

He was not satisfied with his progress in 1972, and after watching his role model Brendan Foster on television finish fifth in the Olympic 1,500, he did some serious reassessment of his career, putting his thoughts into writing. After admitting that he had a great set-up with Anderson, his partner Linda and friends and relatives, he concluded that he had to work on himself: “The end product must be David Moorcroft. Well trained, strong, utterly determined to win, convinced of [his] ability, relaxed yet rock hard, modest yet convinced.” He felt he had been “going too much through the motions” in training. He needed to “continue and improve” weight training and to work on “tactical appreciation.” In general terms he needed to show “more determination providing consistency” and to “become harder and win.” (RC, p.33) This is how future champions think!

Loughborough Years

The routine he had practiced for the last two years could not be continued once he arrived at Loughborough. There was a lot of extra physical activity on the syllabus; it was hard to find the energy to run proper sessions as well. Nevertheless, he was in good shape early in 1973, running the fastest short leg in the AAA Road Relay. After a reasonable fourth in the Inter-counties Mile (4:07.7), he posted a fine Mile PB at Loughborough (4:01.9). Another PB came in June when he clocked 3:43.0 in the British Games to finish second behind Phil Banning. This earned him his first Senior vest for the GB v GDR match in Leipzig. He finished third behind East German Justus and Banning in 3:45.5. Two weeks later, he surprisingly failed to get through the 1,500 heats in the AAAs, running 3:49.5.

1973 was also notable for Moorcroft’s debut over 5,000 in a modest 14:31, Then he bounced back from his AAA disappointment with another 4:01.9 Mile, running fifth behind Jipcho, Quax, Banning and Wilkinson. But his season ended on a disappointing note with a seventh place in the Commonwealth Games Trials. (3:53.8). Thus, although the year showed some promising results, he still had a way to go to reach the top. Bearing in mind that this had been his first year adapting to Loughborough, he could still be satisfied with some progress.

The same might be said about his next season. Moorcroft called his 1974 season “undistinguished”: “There were…up and downs, but I was working hard and investing in the future.” (RC, p. 49) He was eliminated again in the 1,500 heats of the AAAs (3:44.5), and ran some really poor races: last in 4:04.1 in a 1,500 at Loughborough and seventh in the Emsley Carr Mile in 4:11.5. It was perhaps fortunate that Anderson moved south to Nuneaton at this crucial time. He recalls, “We were able to share more time together and indulge in many more conversations and discussions over a wide range of topics…. This sharing process arrived at the right time in David’s development from boyhood to manhood.” (Anderson, “Breaking”)

Finally in 1975, his prospects improved. After two early 5,000s (14:11.8 and 14:06.8), he ran a fast 1,500 at Loughborough (3:43.0). This earned him his first invitation overseas in Belgrade. He took full advantage of this opportunity to win in a new 3:40.7 PB. Six weeks later in Gateshead he ran his first sub-4 Mile (3:59.9) in finishing fourth behind Walker, Boit and Liquori. Things looked up when he finally qualified for the AAA 1,500 final with a 3:40.52 PB. But he had a disastrous final finishing last in 3:51.3. He bounced back with three wins: 3:42.2 in the British Isles Cup, 3:58.8 in the Greater Manchester Mile, and 3:54.9 in an international 1,500 against Sweden. Then he finished off his 1975 season with a fourth place in the Students’ International Games in Rome (3:42.58).

First Olympics

|

|

Moorcroft also excelled in cross-country. Here he follows Lopes of Portugal. |

This 1975 season was a big improvement over the previous two, with some good wins and PBs over 1,500 and the Mile. But entering an Olympic year, he hardly looked like a good prospect. Nevertheless, Montreal was now his goal: “My every step that winter was designed to help get me there as a member of the British team.” (RC, p. 51) His mileage was now up to 90-100 a week. This increase showed to good effect in the National Cross-Country race, for he finished a very impressive second—quite an amazing show of stamina for a miler. As well, he became the British indoor champion with a fast 3:45.6. These demonstrations of both strength and speed bode well for the summer. Could he get to Montreal after all?

Moorcoft’s track season was complicated by his final Loughborough exams in the last two weeks of May. Before these he managed to run the Olympic qualifying time with a 3:40.2 win in Athens. And then with his exams done, he was able to fully concentrate on the Olympic trials in June. He won his heat comfortably in 3:43.69 and the next day, despite feeling “so nervous, so paralysed with fear” (RC, P. 53) he ran a fine 3:39.89 PB to finish second to Steve Ovett. After a steady 2:01.1 at 800, the pace picked up. He kept close to Clement at the front and passed him in the home straight, only to be passed at the tape by Ovett. But with a second place in the trials, he was now in the team for Montreal.

It had been a long haul. After showing great promise as a Junior, he had been through some mediocre years in the early 1970s. But under Anderson’s coaching he had stuck to a steady training regime, never flagging when the results were discouraging. At the same time he had worked through college to earn his O-levels and a teaching qualification (with Honours). Now he had achieved his goal of reaching the Olympics.

Olympic Finalist

|

|

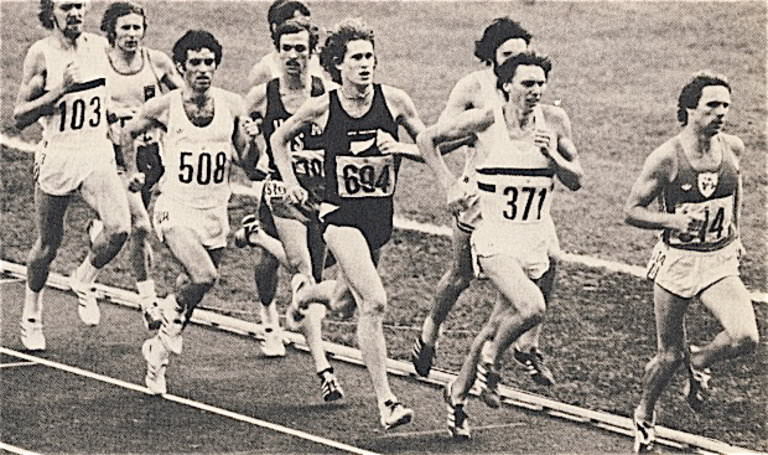

Up with the leaders in his first Olympic final. Moorcroft (371) follows Coghlan with Walker just behind. |

Realistic about his chances—he was ranked 31st in the field--he made reaching the final his goal. This would surely test his strength as the heats, semis and finals were on consecutive days. His heat went well; he qualified easing up behind Coghlan in 3:40.7. In the semi he faced Walker, Ovett and Wessinghage. The top four would qualify. This was a very tense race that ended with a sprint from 300 out. Moorcroft was sixth at this point but a 39-second last 300 put him in third place behind Walker and Crouch of Australia. He had eliminated both Wessinghage and Ovett.

Moorcroft was on top of the world: “Reaching the final was to me like winning the gold.” (RC, p. 59) Anderson had difficulty getting him to focus on the final. Starting on the inside, he was in the front for the first lap (62.5) before Coghlan took over. The pace stayed quite slow (2:03.2 at 800). Coming up to the bell, there was a lot of jostling for position, and when a gap opened up, he went for it. Unfortunately Ivo Van Damme got through first, and Moorcroft ended up with a spike injury. Despite giving it his all down the back straight, he could not cope with the likes of Walker, Van Damme and Coghlan. Even Frank Clement managed to pass him. Seventh in 3:40.9. After an initial disappointment, he managed to put things in perspective and appreciate that he had achieved his goal of reaching the final—quite an achievement for someone ranked 31st in the field.

After the Games, Moorcroft was able to take advantage of his good form. After placing second in the AAA 1,500 behind Rod Dixon, he set PBs in both the 1,500 and the Mile. In both races he also ran well competitively. In the Zurich Weltklasse he did well to finish fourth in a stellar field, setting a 3:38.91 PB. Then in the Emsley Carr Mile he had a big win over Bayi, Foster, Clement and Malinowski. A 3:57.06 PB was the icing on the cake.

A Year Lost

After this breakthrough following several years of less than satisfying performances, everyone expected he would continue his progress in 1977. On returning from the Olympics, he felt “that the experience had hardened me for the future, and that I could now compete with a greater confidence.” (RC, p. 64)

He was able to get time off from his new teaching job to run in New Zealand in January. In great form, Moorcroft won four of his five races, only to be defeated in his last by Walker. There were some encouraging times: an 800 PB of 1:50.9, and two fast 1,500s in 3:39.8 and 3:40.3. The only thing he did wrong was to play a round of golf and initiate a back injury that would prevent him from racing for a whole year. It was eventually discovered that his fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae had compacted.

Back in Action

It was not until the fall of 1978 that Moorcroft was running again. At the end of the year he was ready for some competition in New Zealand. This time a very fit Eamonn Coghlan was there, so Moorcroft won only two of his six races. Still, he improved his 800 PB fractionally with 1:50.8 and ran a respectable 4:02.9. After a full year off competition, this was encouraging: “I was working hard and knew I was on my way back.” (RC, p. 70) He was now looking forward to the European and Commonwealth meets in the summer.

The season started well with two 1,500s: a second behind Wilson Waigwa of Kenya (3:39.36) and a win in the AAAs (3:42.92). But the first indication that he was in really good form was a Mile in Gateshead in early July. In this race he beat Foster and Clement in a PB 3:56.60. This very encouraging win set him up well for the Commonwealth Games in Edmonton.

Commonwealth Champion

|

|

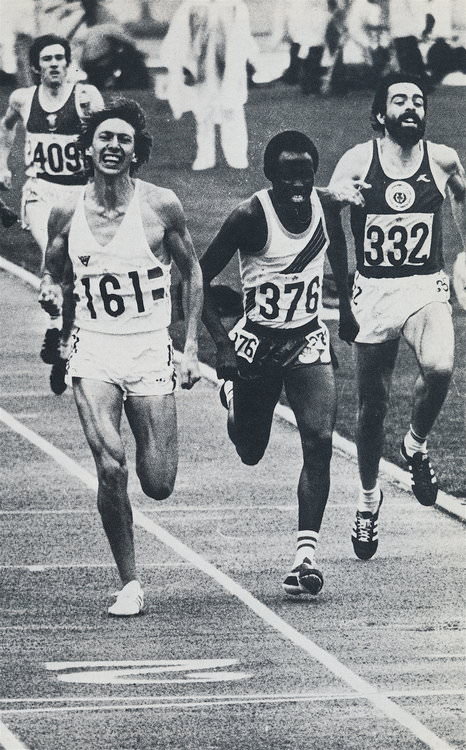

1978 Commonwealth 1,500 title. Bayi finishes second. |

With Ovett opting out and Walker recovering from surgery, the favorites for the Commonwealth 1,500 were Waigwa and Bayi, the current champion and world-record-holder. Waigwa had recently beaten Bayi in the Oslo Mile with 3:53.2. The British contingent was also strong: Moorcroft was accompanied to Canada by Foster, John Robson, Frank Clement and Graham Williamson, all of whom had run the Mile in the 3:54-3:56 range.

As usual, Bayi blazed the pace with 57.7, 1:55.2. This was fast for Moorcroft, and he admitted later that he didn’t dare look at the clock! “I wasn’t sure whether to go with Bayi and risk dying, or [go] for a safe silver,” he said afterwards (Cordner Nelson and Roberto Quercetani, The Milers, p. 425) Bayi maintained his fast pace, and Moorcroft kept with him and Robson. At the bell (2:53.9) Moorcroft was still in third. Nothing much changed at the front until the last 100, except that Robson and Moorcroft closed right up on Bayi round the final bend. As the leaders entered the final stretch, Robson moved up to challenge Bayi, who resisted. While these two were having their private battle, Moorcroft passed them both in a marvelous burst that earned him just a 0.1 second advantage at the finish. With Clement finishing faster than anyone else, the first four were barely separated: 1. Moorcroft 3:35.5; 2. Bayi 3:35.6; 3. Robson 3:35.6; 4. Clement 3:35.7.

Moorcroft later described his thoughts during the last 100: “As we came into the final straight I remember thinking, I’ve got a medal here, and when Robson tried to edge ahead of Bayi and I could feel that my final sprint was going to overtake both of them, I thought: it’s going to be the gold!” (RC, p. 76) He had run the fastest time of the year and beaten his previous best by 3.4 seconds—all when it really counted. It was a big step up from an Olympic finalist to a Commonwealth champion.

1978 European Championships

With three weeks until the Europeans, Moorcroft raced three times to keep tuned: an 800 PB in 1:49.15, a 1,000 in 2:21.5 and a 3,000 PB in 7:43.51. The 3,000 was especially impressive; not only did he improve his best time by 15 seconds, but he won from a stellar field that included Rod Dixon, Nick Rose and Marty Liquori.

|

|

Moorcroft (right) finishes third in the 1978 European 1,500 behind Ovett (unseen) and Coghlan. |

The field for the European 1,500 final included Wessinghage of Germany and Plachy of Czechoslovakia, who had both run 3:52 for the Mile in Stockholm, and Strauss of Germany, who had clocked 3:36 for 1,500. But the favorites were Ovett and Coghlan, both great competitors and both in form. Moorcroft was facing an even better field than the one in Edmonton.

He stayed in the pack for the first three laps. The race was not as fast as the Commonwealth: 57.5, 1:57.7, 2 :56.7. He was well placed down the back straight of the last lap, but when Ovett went with 200 to go, he had no answer at all. Ovett had a 10m lead over Moorcroft coming into the final straight. Still, it looked like the silver was his. But just before the finish, Coghlan passed him: 1. Ovett 3:35.5; 2. Coghlan 3:36.57; 3. Moorcroft 3:36.70. He was disappointed at the time, but he had been beaten by two runners with superior speed. As well, his run in Edmonton must have taken an edge off his performance.

Although tired, he raced and won three more times. In Frankfurt he ran a PB Mile in 3:55.3, defeating Wessinghage and Flynn. Then he ran 3:36.6 for 1,500, winning by 10 seconds. Finally in London he won another Mile in a fast 3:55.43, beating Williamson, Clement and Bayi.

Moorcroft’s 1978 season had been close to perfect with two major medals and four PBs. But his European experience made it clear that his basic speed was not quite good enough for Championship 1,500 races. Ovett’s burst had left him standing and Coghlan’s late burst had pushed him back to third. Moving up to 5,000 was clearly a sensible step at this point in his career. Mel Watman, in writing about Moorcroft’s Commonwealth victory, had made the following prediction: “Relatively slow at 800…but a fine road and cross-country runner…Dave could—when the time is right—become Britain’s next great 5,000 star.” (Athletics Weekly, August 26, 1978)

NZ Again

Moorcroft returned to New Zealand at the end of the year and trained there for five months. Clearly more focused on conditioning, he competed only three times. This groundwork showed immediate results as he ran a PB Mile in 3:55.1 in Jamaica on his way home. Then a week later he won the Bannister Mile in London by over two seconds with 3:56.3. In June he ran his only 5,000 of the season as an experiment: “I had talked to John Anderson about eventually moving up to 5,000 metres,” he wrote later (RC, p. 83) His easy victory in 13:30.33 was a 28-second PB. But there was a new injury concern with pain in his calves.

He continued competing, winning the 1,500 in the semi-final of the Euro Cup and finishing second to Plachy in a Mile at Gateshead. He now developed a hamstring problem and had to get treatment. Nevertheless, he ran a PB 800 of 1:48.54 to qualify for the AAA 800 final. He managed to run as fast in the final (1:48.60) but this earned him only seventh place. The 800 was part of his preparation for the Golden Mile in Oslo three days later, a race that was to be the last of his season.

The 1979 Golden Mile was one for the history books as Seb Coe broke the world record with 3:48.95. It was a humiliating experience for Moorcroft, who despite setting a PB of 3:54.35, was way back in ninth position: “It certainly did not feel like a personal best; it felt like a disaster. I was washed out, demoralized…. I decided to end my 1979 campaign right there.” (RC, p. 84) This race was another indication that he needed to move up to the 5,000.

Conditioning for the 1980 Olympics

Despite his painful calves, Moorcroft focused on another winter of conditioning. After an unsuccessful experiment with altitude training, he again returned to New Zealand, where he was able to train in a warm climate and carry out speedwork on “a first-class surface to avoid injury.” (RC, p. 86) During the first months of 1980 he thought a lot about which event to choose for the Olympics. He realized that he didn’t have the speed of some of the 1,500 runners like Coe and Ovett, but he thought that his superior strength might give him an edge with the demands of heats, semis and final of an Olympic event. As for the 5,000, he had run only one 5,000 in 1979 and lacked the experience needed for this event.

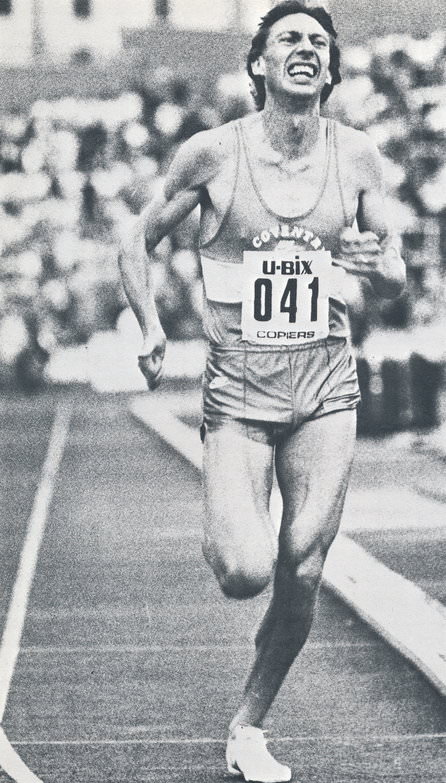

|

|

Moorcroft suffering in the 1980 Olympic 5,000 semi-final. |

In early 1980, he raced five times in New Zealand. In two 5,000 races he finished first and third, each time running just under his 1978 PB with 13:29.4 and 13:29.1. These two races helped him to choose the 5,000 for his Olympic goal. Again he was in form as soon as he competed in Europe. He won three consecutive 1,500s, including the AAAs. Then, after a respectable 13:41.8 5,000 victory in the UK Olympic trial, he lined up for a big Two Miles race in the Talbot Games with a big problem: his calves were very sore and there was evidence of internal bleeding under the skin.

The Two Miles was led out by Bayi and Moorcroft, with the first mile covered in 4:06.9. This world-record speed wasn’t maintained; the last lap urned into a sprint, which Moorcroft won. His 8:18.6 was very encouraging. But all his Olympic preparation was for nought. He caught a stomach bug in Moscow, and although he managed to qualify for the semi-final with 13:42.96, he was eliminated in the semi with a ninth place in 13:58.23. Determined to run some fast times once his stomach had recovered, he left Moscow before the 5,000 final.

Back to the Grind

But that year he never really recovered psychologically from his Olympic disappointment. “Half of the problem,” he wrote later, “was that the inner motivation was no longer there.” (RC, p. 92) In eight races he achieved one PB (800 in 1:48.37) and won just one race--well, he tied for first with Nick Rose. His best races were over a Mile (3:55.73) and 1,500 (3:38.19 and 3:39.70).

After competition ended, Moorcroft spent a few months in the USA, racing a couple of times on the road and once indoors. Then, before returning home, he made a short trip to New Zealand for a few races. He won a couple of fast Miles (3:54.37, 3:55.49) and then won the 5,000 in the Pacific Conference Games (13:36.79). Back home he decided to run the demanding English Cross-Country Championships in early March. Unfortunately, he was still putting on his shoes when the gun went off. The 2,200 runners were all ahead of him once he started running. By the end of the first three-mile lap he had passed all but thirty of them. After the second lap, he was in 12th place. Over the last three miles he moved up even more to finish fourth place—an amazing performance in a race where the start is so important. He didn’t run as well in the World Championships three weeks later, finishing a lowly 91st, 1:39 behind the American winner Craig Virgin.

His 1981 track season began modestly in June with a 13th place in an international 5,000. (13:37.51). But after that he was beaten only once in 11 races. It was a remarkable competitive record. One highlight was a win over 5,000 in the European Cup Final (13:43.18). He also lowered his 5,000 PB by almost ten seconds to 13:20.51. He was still having problems with his calves during this period: “Both legs felt as though they were continually clamped in a vice,” he told Mel Watman. (All-Time Greats of British Athletics, p. 119). Finally compartment syndrome was diagnosed.

Surgery

He was operated on successfully on September 9 and began running again less than a month later. In the new year he was back in New Zealand for conditioning and racing. This time he raced six times—more than usual. He won two 5,000s (13:36.82, 13:31.22) and ran a couple of sub-4s, each time finishing behind Steve Scott and John Walker. Then it was back home for the English Cross-Country Championships, where he finished fourth again—a great run considering he had stomach trouble during the race.

A remarkable track session confirmed he was in the best form of his life. Just before a record-breaking run in the national road relay, where he broke Brendan Foster’s course record, he did a 5x1,000m session. His times were all at sub-4 speed: 2:29, 2:28, 2:28, 2:27, 2:28. His recovery was a six-minute 1,000m jog. Still, the European and Commonwealth Games were still a way off, so his plan was not to race too much in the early summer.

He raced only twice in June. First he won a 3,000 in 7:52.5 after uncharacteristically taking the lead at the halfway mark and running 2:29 for the last K. Then he went to Oslo for the Dream Mile, hoping to improve on his 3:54.37 PB. He was up against the very best: Scott, Walker, Maree, Flynn. The pace was fast from the start: 54.8, 1:53 and 2:53.9. Moorcroft managed to stay with the leaders at this pace and finished third behind Scott and Maree and ahead of Walker and Flynn. The best news was his time: 3:49.34. It was a five-second PB: “It confirmed my feeling that I was at last beginning to reach the level of performance of which I had felt capable but had in the past never been able to reach.” (RC, p. 113). The performance he had been working towards was the 5,000 in Oslo.

Personality Change

Deep down inside his consciousness, Moorcroft had come to realize that this 1982 season was to be his main chance, perhaps his final chance, to do something really big. This almost subconscious realization, manifested itself in a strange way: “I was in the form of my life, yet curiously I was unhappy and disturbed inside…. [In training] I could reach down to a new level of intensity which I had never before approached. But in my own mind and in my everyday life, I was going through an uncharacteristic turmoil which is almost frightening to recall now.” (RC, p. 109)

He had noticed this personality change before the track season started: “In early 1982 my attitude changed. Never had I felt so masochistic and aggressive in my training…. For a span of between three and six months for some reason I was not a particularly pleasant person. I felt very frustrated at that time, but the change which came over me was both quite uncharacteristic and, in retrospect, puzzling.” (RC, p. 110)

Of course, his wife had noticed this change. “I seemed to be behaving oddly,” he recalled, “like driving the car at nearly 100 mph on the motorway whenever possible and being moody and taciturn at home.” And his coach was concerned about the different Dave Moorcroft who turned up for training sessions and who did his session like a man possessed but never talked to anyone. Moorcroft remembers, “I genuinely didn’t care what happened, yet I was taking everything out on myself in training… It was almost as if I was punishing myself, or taking solace in the one thing in which I did not find frustration.” Overall, his need to run well was much more acute than normal, “almost animalistic in the way I was training.” (RC, p. 111)

Later he tried to analyse what was going on inside him: “So far as running went, it may have been brought about by a fear of finally having to face my destiny…. I had to face up to the fact this was the moment of truth, and perhaps I was scared of failure, of discovering after all I could not do it simply because I could not do it.

“Perhaps I was training like a lunatic just to try to minimize the chance of failure, whatever that constituted. I felt like a parachutist about to step out of an aeroplane for the first time. I had been through the mock jumps, and the jumps from towers attached to safety harnesses. But this time it was real. And I felt terrified. (RC, pp. 111-112)

Just before his big 5,000 race in Oslo, he seemed to be recovering: “I seemed to be coming out of my black depression, but I still felt somewhat confused and unsettled in my everyday life. That time was the closest I had ever been to believing that you have to be nasty to win, and that nice guys only come second.” (RC, pp. 113-114)

He then talked it all over with coach, who told him he had been “a miserable sod lately”: “I think that acknowledging its existence was possibly the first step towards eventually clearing it up.” (RC, p. 114)

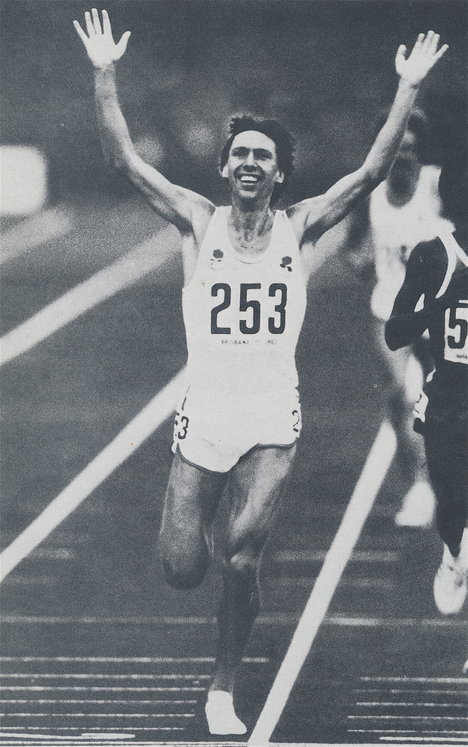

World Record

|

|

The last moments of his 13:00.41 effort in Oslo. |

His 5,000 race in Oslo was the last event of the evening. Earlier, Steve Scott has thrilled the crowd with the second fastest Mile of all time (3:47.69), so the atmosphere in the stadium was electric. In the field were two Kenyans who had almost beaten the 13:06.20 world record the previous evening in Stockholm: Henry Rono and Peter Koech, who had run 13:08.7 and 13:09.50. The rest of the field were British runners, notably Nick Rose, Dave Clarke and Steve Binns.

Before leaving for Oslo, Moorcroft had concluded that he should be able to improve on his 13:20.51 PB, and he set Brendan’s Foster’s UK record of 13:14.6 as his target. Thus he would need to average about 64 seconds per lap. Henry Rono’s 13:06.20 world record was originally considered as a target, but despite Anderson telling him that he could break 13:00, Moorcroft felt that 63-second laps were “right out of my reach.” (RC, p.115) With 64-second laps in his mind, he hoped that he would get some early help from the Kenyans, who were rumoured to be planning to attack the world record.

He was in for a shock. From the start, no one wanted to take the lead, and the field slowed right down after the first bend. “Suddenly I could see my hopes beginning to crumble before the race was half a minute old,” he recalled. (RC, p. 117) Fortunately, he was able to react quickly to this unexpected situation: he took the lead and tried to take the field through the first lap in 63. It was 61.4. Surprised at this fast time he slowed on the second lap to 65.8. He was now closer to his 64-lap plan. But then he ran a 61.3—too fast, but he was feeling really good, and the field behind him was already beginning to lag.

It was time for another major decision: should he continue to lead? He was not by nature a front runner, but he was feeling really good, and the crowd was getting excited: “They began to get behind me, rhythmically banging the sides of the stands and chanting to keep me going.” (RC, p. 118) Meanwhile he passed four laps in 4:11.1 after a 62.6 lap. He was now in the zone: “I felt completely in control of myself…. I never once thought about the possibility of being beaten, even though I was now setting an almost irresponsible pace. It was as though my body, spirit and mind were all in harmony; I didn’t even think how fast I was going.” (RC, p. 118) And he certainly didn’t realize he was on world-record pace, even when he passed 3,000 in 7:50, which was exactly 13:00 pace.

Still feeling good, he ran the next K in 2:38, just over 63 per lap, to reach 4,000 in 10:28. Was it possible for him to run the last K in 2:32? At this point he still wasn’t fully aware of the speed he was running. It was only at the bell (12:02) that he realized he had the world record: “I was able to savour that thought on the last lap, for although it was hard and I was very tired, I knew I only had to run 64 seconds to get that record, and I was running much faster than that.” (RC, p. 118)

He managed 58 for the last lap and the clock stopped at 13:00.41. He had broken Rono’s world record by 5.79 seconds and had moved up in the all-time list for 5,000 from 57th to first. It was a huge breakthrough that left him and the rest of the running fraternity stunned. He was the first Briton to hold the 5,000 world record since Gordon Pirie ran 13:36.8 in 1956.

More Fast Times

Overnight he became famous. And another big win over 3,000 ten days later in London added to that fame. The field was full of the world’s top runners: Walker, Maree, Ovett, Koech, Scott, Waigwa, Boit, Wessinghage. This time Moorcroft was focused on winning; records were not his concern. The field went through 1,500 in 3:48.5 and then Moorcroft went to the front: “I did not want to risk everything coming down to the last lap sprint. I had already lost to Scott and Maree in a fast Mile, so it was important that I made them hurt from farther out.” (RC, p. 126) Koech, Boit, Scott, Maree and Walker went with him, but his pace soon thinned out the chasing pack.

By the bell, only Maree was still with him. After two challenges from the American, a confident Moorcroft let him by at 200 to go. Then he kicked off the final bend and won in the fast time of 7:32.79, less than a second outside Rono’s world record. But the time was secondary for Moorcroft; the main thing was that he could race. This fine victory gave him even more media coverage. As Norman Fox wrote, “For Moorcroft, fame has come after 15 years and one special month. The month has brought more attention than the previous 15 years, when he was known as a jolly good chap, working hard for a few medals and the esteem of his fellow athletes.” (Times, July 18, 1982) Fox went on to write, “For the moment Ovett and Coe are relegated on the wanted list of entrepreneurs.”

Moorcroft’s 1982 season wasn’t nearly over. He ran a PB 800 in the AAAs with 1:46.64 in fifth place. And then he improved his 1,500 PB with a victory in Hengelo (3:33.79). That was his fifth PB in four weeks, so not surprisingly he began to show signs of fatigue (an eye infection and swollen glands). Still there were some more commitments. He had to run a Two Miles in the Talbot Games, winning in 8:16.75 from Peter Koech. He had to run the Emsley Carr Mile, which he won in 3:57.84. He was still winning, but he was competing reluctantly, and the European and Commonwealth Games were ahead.

1982 Euros and Commonwealth

|

|

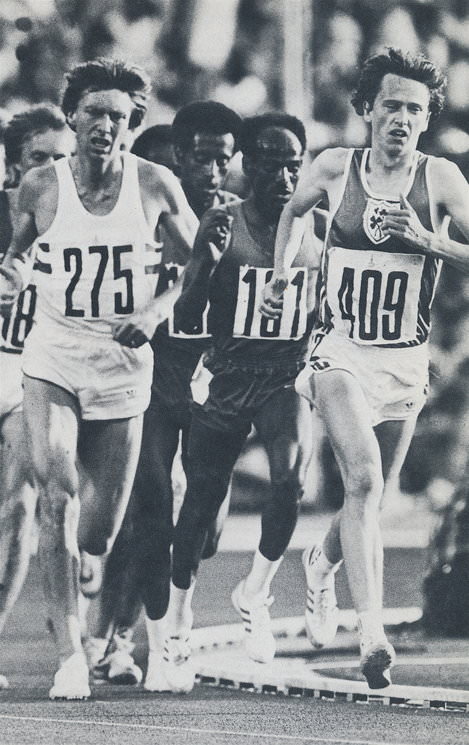

His second Commonwealth title, this time in the 5,000. |

The European 5,000 was first and promised to be the bigger challenge. There were several good German runners in the final, with Wessinghage, fresh from a European 2,000 record. Moorcroft tried leading again as it had been a successful tactic earlier in the season. But he didn’t feel good leading. When he dropped back into the pack, the pace slowed. He was back in the lead with 800 to go. He admits that during this stage his concentration “began to wander”—a sure sign of mental fatigue from his long and eventful season. Uncharacteristically, he was caught napping just before the bell and suddenly found himself badly boxed in with six runners passing him.

Finally extricating himself, he managed to get back into second with 200 to go. But Wessinghage had got away. Moorcroft was unable to catch him, and near the finish he was passed by Schildhauer. He was third in 13:30.42, a disappointing run for the world-record-holder: “I felt really rough in the home straight and was surprised…only Schildhauer came past me before the line.” (RC, p. 131)

Clearly needing rest, he was able to opt out of some race commitments and managed to regain some freshness before the Brisbane Commonwealth Games. An added break for him was that the heats were cancelled. He was a different competitor from the tired one who struggled for a bronze in the Euros. After Koech and Barie set the pace, Moorcroft took charge of the race at 4,000. He ran laps of 64.8 and 60.5 and then sprinted the last 200 in 25.7 for a three-second victory over Nick Rose. It was his second Commonwealth gold.

Breakdown

Such a hectic competitive year finally took a toll on his health. His training times began to slow at the end of the year. And when he tried racing in New Zealand (8:40 in a 3,000 and 1:58 for an 800), it was obvious that he was ill. Back in England hepatitis was diagnosed. Plans for a late 1983 track season were then cancelled when he developed a stress fracture in his foot. So the focus now became the 1984 Olympics.

His first race back was a 3,000 win on September 9, 1983, in Jarrow (8:10.33). He showed his strength had returned when he ran second to Tim Hutchings in an international cross-country race in December. Then it was back to New Zealand. But his health was still fragile; he came down with a sinus infection. His first race was a disastrous 5,000, where he finished 12th in 14:21.3. A month later he appeared to have recovered as he won a 10K road race and ran a 5,000 on the track in 13:34.0.

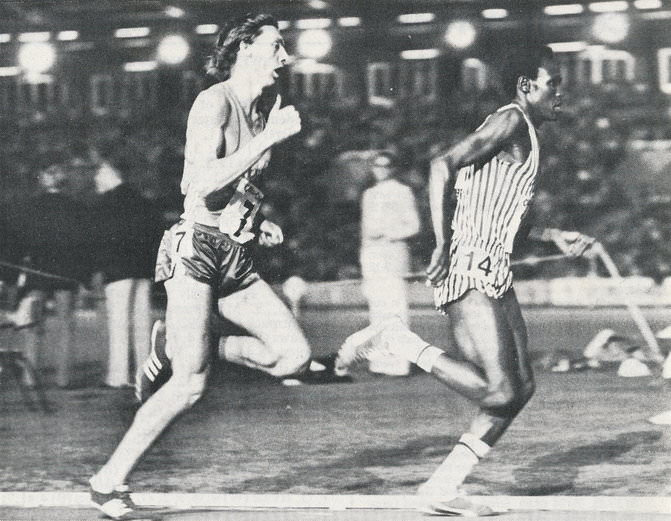

|

|

Moorcroft's competitive tenacity is evident as he tracks Filbert Bayi. |

As he passed his 31st birthday, Moorcroft was preparing seriously for his third Olympics. But his preparation was severely handicapped by a recurring virus and a displaced pelvis that caused a lot of pain when he ran. In the month before the Games he managed to race three times. He started with two wins over 3,000 (7:48.88, 8:00.68), and then went to Norway for the Dream Mile.

His wonderful win in this Oslo Mile came just two weeks before the Games. Considering his erratic training in recent months, he must have been delighted with the fast 3:50.95 time and with his win, albeit against a weaker field than usual. Still, he was well aware that the Olympic 5,000 wasn’t just one race, but three. The question was whether his conditioning would enable him to run well in the final after a heat and a semi—all in a four-day period.

Third Time Unlucky

In Los Angeles, his Olympic heat was comfortable enough as he placed second in a slow 13:51.40. The semi-final was tougher, but again he was a comfortable second in 13:28.44. But his pelvis injury was aggravated by these two races in a 24-hour period—despite daily hospital treatment. Thus it was a quite different Moorcroft in the final. While Aouita blazed to a brilliant win, Moorcroft hobbled round the 12.5 laps in pain and finished 14th and last, 1:11 behind the Moroccan in 14:16.61. Most runners would have dropped out. Not Moorcroft. “I probably should never have gone [to LA],” he said after the race. “But at least I know I did all I could. It would have been worse not to go and think maybe I could have won it. I’m still in good shape; there’s nothing wrong with my fitness. It’s now a case whether I can run without pain.” (Times, Aug. 16, 1984)

Winding Down

It took a while. The next year was a write-off, and it wasn’t until April of 1986 that he competed again—for his club in the National Road Relay. He managed to keep healthy throughout the track season, racing ten times from June to September, but he wasn’t the Moorcroft of 1982. There were a couple of good wins over Vainio and Waigwa, but otherwise his performances were below par. He ran three sub-4 Miles, a 5,000 in 13:40.58 and a brisk 2,000 in 5:02.86.

Persistence was his middle name. He was back in 1987 and ran eight races in the summer. He was not winning anymore, but he clocked some reasonably good times: 7:46.63 for 3,000 and 13:29.17. He was able to give Steve Ovett a good race over 3,000, losing by only 0.18 of a second, but he could place only 7th in the AAA 1,500.

The next year, the 35-year-old still had some speed in his legs, but his best 5,000 time was a minute slower than his world record. He raced only five times, with his best time being a 7:53.71 for 8th place in a 3,000 in Bern. His last season was in 1989. In seven competitions he raced over 3,000 four times, winning twice. His best race was a third place (7:50.50) in an international match behind Tim Hacker and Mark Rowland. But in his last track race he could finish only 22nd in the AAA 5,000.

Master’s Mile

But Moorcroft’s story isn’t quite over, for he kept himself in running shape until 1993, when he hit 40 and became a Master. He was one of three runners thinking seriously of becoming the first master to run a sub-4 Mile. John Walker looked most likely to do it, and Eamonn Coghlan had working towards the same goal since 1991. Then Walker had to quit running because of injury problems, so it was between Coghlan and Moorcroft. Coghlan got agonizingly close in early 1993 with an indoor 4:01.3. Moorcroft made his attempt in Belfast in mid-June. He was with the lead group for three laps and well on schedule for a sub-4, but the last lap was his undoing, and he finished in 4:02.53. It was a masters outdoor world record but not under 4:00. This was his only serious attempt on the 4:00 Master’s barrier, and it was a brave one.

Conclusion

True to his character, Moorcroft has kept busy since he retired from competition. He has worked with great success for the BBC as a sports commentator (1983-1997), as Chief Executive for the Coventry Sports Foundation (1981-1995), and as chief Executive for UK Athletics (1997-2007). Since 2007 he has run a sports consultancy business, pointfourone, with Rob Borthwick.

He can look back on a long running career where perseverance played a key role. Full credit should also be given to his longtime coach John Anderson who supported Moorcroft throughout his career, adapting his role as his athlete matured. Anderson’s training regime that insisted on running fast throughout the year worked well for Moorcroft, although it did make him more susceptible to injury. But he always managed to keep his athlete positive. “There have been setbacks and disappointments, but they have been used as spurs towards greater achievements,” he once told Alastair Aitken. (More Than Winning, p. 221) And greater achievements there were.

---

Training with John Anderson

John Anderson used many of the contemporary training methods for milers. In developing what he called his “Composite Programme,” he studied many research physiologists.

The “dominant influence” in this programme was speed: “I believe that, in order to run fast, the athlete must be conditioned both physically and mentally to the experience of running fast throughout the entire period of his running career…. The skill of running fast is a learned achievement and, in order to be developed and sustained, must be regularly inculcated in the regimen of the practicing athlete…. Running fast is as much a condition of the mind as it is of the physiological components.” (Anderson, “Breaking”)

Thus Anderson employed one crucial variation on conventional middle-distance training: throughout most of the year he had Moorcroft carry out two interval sessions at his racing speed. These two sessions were not fixed but there were two “key” sessions listed by Poole: (1) 4-5x1,000 [7:00 recovery]; (2) 4x600 [3:00 recovery] and 6x150 [1:30 recovery]. (“David Moorcroft: Analysis of a Champion,” BMC News, Spring 1999)

Of course, these repetitions got faster over the years. By 1982 he was able to run 6x1,000 in 2:26. However, Anderson did not emphasize progression in training times: “The thing to do is let effort dictate pace. Your guide is the ability to sustain quality.” (Moore) The main point was that his athlete was accustomed to running at racing speed all the time.

Anderson’s Composite Programme involved three facets: Aerobic, Anaerobic, and the “Link” between aerobic and anaerobic. The aerobic facet involved long slow runs, fast runs of 3-6 miles, medium intensity 8-12 Mile runs, and fartlek. The anaerobic facet, all carried out at above 80% effort, involved short reps with short recovery, longer reps with longer recovery, technique running allied with acceleration, flat-out reps with longer recoveries, as well as a combination of these four modes.

The “Link” used two principal sessions: 8x300 [3:00] and 4x600 [5:00]. In these sessions “the athlete is attempting to relate the speed developed within the shorter sessions and the endurance developed with the aerobic sessions.” (Anderson, “Breaking”) These Link sessions are all-out efforts where the athlete averages the fastest time possible. As he developed, Moorcroft was able to run the 600s in 82, so Anderson changed the 4x600 session to 4-6x1,000 [6:30]. From the coach’s aspect, the Link sessions were a yardstick of his athlete’s progress.

Anderson realized right away that although Moorcroft possessed good endurance, he lacked the natural speed of an Ovett. Thus his approach to speed was especially useful for Moorcroft’s development. Although he still developed his athlete’s endurance by gradually building weekly mileage to 100, there was more focus on speed. An important regular session involved a series of short sprints at 95-100% effort. This session would be four sets of 4x60 or 4x100 [0:30] with 2:00 between sets. As well as developing speed, this session, according to Anderson, improved tolerance to lactic acid and increased the capacity for oxygen supply. A variation on this session was three sets of 4-6x150 or 200, where the focus was on technique. This session improved “the capacity to endure high oxygen deficit and lactic-acid build-up.” (Anderson, “Breaking....”)

The best two analyses of John Anderson’s training principles are 1) John Anderson, “Breaking the Thirteen-Minute Barrier,” 12th Congress of the European Coaches’ Association on Distance Running, 1983); and 2) Norman Poole, “David Moorcroft: Analysis of a Champion,” BMC News, Spring 1999.

6 Comments