Marty Liquori Profile

b. September 11/1949

|

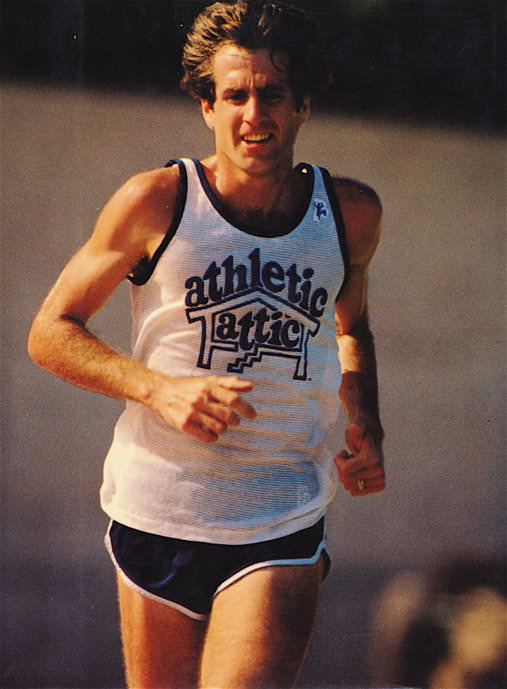

Marty Liquori in full flight, still viewable on the Internet, has to be one of the finest sights in competitive running. He appeared on the running scene in 1967 as the third American high-schooler to break the 4-minute mile. The 17-year-old from New Jersey was only seventh in the Bakersfield, California, race and finished 8.7 seconds behind the winner Jim Ryun, who broke the world record with 3:51.1. Within two years, this talented runner was defeating Ryun in major races. Under the coaching of Jumbo Elliott at Villanova University, the dedicated Liquori quickly emerged as the world’s top 1,500 runner in 1969. A fierce competitor, Liquori looked a sure bet to dominate the 1,500 for many years. But this never happened. His harsh training schedules and frequent indoor competition led to a string of injuries that kept him out of some major competitions. And although there were many really fine performances throughout the 1970s—he was the world’s number one over 5,000 in 1977—Liquori never quite fulfilled his early promise, and he ended his long career without a major title.

Schoolboy

Marty Liquori grew up playing baseball (as a catcher) and basketball. On entering high school, he dreamed of becoming a basketball player. To get in shape for basketball, Liquori followed the coach’s wish and ran cross-country to get in shape: “At last I’d found an activity where I could work as hard as I pleased, where I could control my future and my success or failure.” (On the Run, p. 89) Showing running talent, Liquori quickly switched from basketball to running.

His high-school coach, Fred Dwyer, a 4:00.8 miler and Villanova graduate, believed in the killer attitude, a runner’s concept that had been promoted by Australian coach Percy Cerutty. This attitude required hating your opponents. Dwyer soon had the young Liquori believe in this concept. Before races he would not speak to anyone, not acknowledge greetings and not shake hands on the start line. “Some people thought I was nuts,” he wrote in his book On the Run. “I guess many of them thought I was some kind of animal.” (OTR, pp. 92-3)

Liquori now admits that he became obsessed with running in the early stages of his career. He wanted to break four minutes while still in high school, he wanted to make the 1968 Olympics as a teenager and he wanted to be the world’s number one by the time he was 19. It says a lot for both his natural talent and for his determination that he achieved all three goals.

Coach Dwyer

A lot of credit for Liquori’s early development must go to Fred Dwyer. With the intuition of a good coach, he was the first to see talent in a nondescript Liquori: “Marty? Oh skinny. Obscure. I hate to use the word nonentity but he was close to that.” (OTR, p. 116) Then he knew how to bring out that talent by challenging the teenager until Liquori “actually hated” him. Dwyer told the newcomer Liquori that he wasn’t strong enough to run the Mile, so Liquori responded the following summer “by running 70 miles a week along the beaches of the Jersey shore.” (OTR, p. 116) Dwyer still didn’t let him run the Mile and began to belittle Liquori’s group with teasing and name-calling. While some runners quit, Liquori responded in the way the coach had hoped by taking up the challenge in anger. Eventually in the middle of his sophomore year, he was allowed to run a Mile and clocked 4:18, a state record. His progress in his Junior year was slowed by a foot injury; he improved only five seconds to 4:13.2.

Liquori’s training in his Senior year was already heavy, between 70 to 80 miles a week. In a 2006 interview with Runner’s World he stressed that the most important weekly session was his weekly15-mile Sunday run. Here is a week in his training log (April 30 to May 6), a couple of months before his first 4-minute mile in 1967: Sunday 15 miles; Monday 10 miles; Tuesday 7 miles; Wednesday 14 miles-weights—swim; Thursday 15x300--8 miles; Friday 20x300—5 miles; Saturday 20x300—8 miles. His log also shows that he didn’t take a day off training in May until the 29th, four days before a big Mile race (4:01).

After a hard winter’s training, he suddenly dropped his mile time from 4:13 to 4:04.4 and headed to California to break four minutes. In Compton he got close (4:01.1) and in San Diego he got closer (4:00.1). Then, missing graduation ceremonies back home, he competed in the AAU championships. In the final he was unable to keep up with the leaders and lagged back in seventh place. Not knowing that Jim Ryun was running a new WR, he thought he was running badly--until he heard 3:02 at the bell. This gave him incentive to burn up the last lap and he crossed the line in 3:59.8 to become the third high-schooler ever to run a sub-4. Shaking Jim Ryun’s hand after the race, he said, “I was awfully proud to be in that race. Thank you for setting that pace.” (Sports Illustrated, July 3, 1967)

Villanova University

Recruited by Villanova University in 1967, he left Fred Dwyer to train under the legendary Jumbo Elliott. He chose Villanova for its coach: “Jumbo had the reputation, and Jumbo turned me on.” (OTR, p. 121) Elliott was just the coach Liquori needed: “His method is a mixed bag, and eclectic blend of showmanship, salesmanship, Irish wit, Irish blarney, parental care, parental discipline, instinct and knowledge. His singular ability is in contrast quite simple; he inspires confidence.” (OTR, p. 121)

Since in the 1960s freshmen weren’t allowed to compete at the NCAA level, Liquori’s first year at Villanova was quiet. He did not have to undergo the grueling varsity cross-country and track seasons. It was a time to focus on training. Liquori had the 1968 Olympic team as a goal, and he was even able to do some altitude training in preparation for Mexico City. Following an impressive 2 Miles in 8:52.4 indoors in February 1968, knocking 12 seconds off his PB, he entered the outdoor track season with good conditioning and gradually rounded into top form for the Olympic trials.

1968 Olympics

|

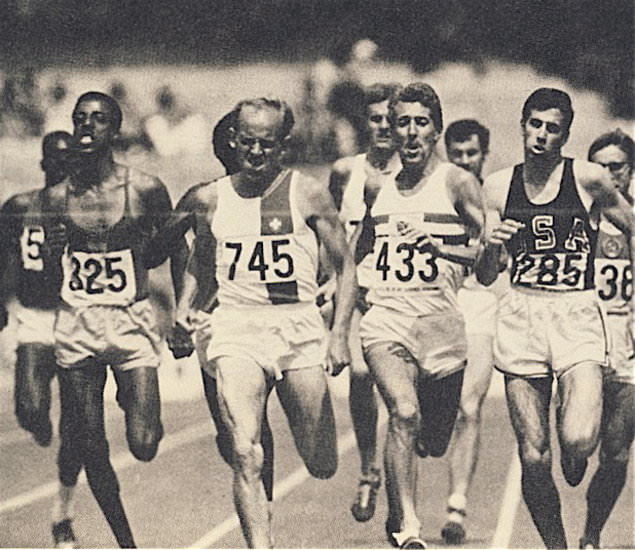

| Liquori (285) finishes fourth in the 1968 Olympic 1,500 semi-final with "an easy run." John Whetton (433) went on to finish fifth in the final, while Liquori hobbled home last. |

His serious racing began on June 8 when he was third in Compton Mile (4:00.7) behind Bair (4:00.0) and De Hertoghe (4:00.5). He lost to Bair and fellow Villanovan Patrick three weeks later in a pre-Olympic trials meet, clocking 3:44.2. By the end of August he was racing well and almost beat Jim Ryun in Eugene. Ryun just caught him at the tape winning in 3:59.0 to Liquori’s 3:59.3. He was peaking perfectly for the Olympic Trials at Lake Tahoe. In the high altitude, the pace was slow. Soon after the field passed 800 in 2:10.5, Liquori took the lead and was still in front at the bell. When Ryun passed him with 300 to go, he was the only one to stay with the WR holder. Qualifying for Mexico, he finished a good second in 3:49.5, half a second behind Ryun, who had run the last 400 in 50.8. Benefitting from not being involved in varsity competition in his first university year, he easily beat two fine varsity runners, Patrick and Bair, who had defeated him earlier but were now clearly past their peak.

Liquori did well to make the 1968 Olympic final. He won his first-round heat in 3:52.7 and placed fourth in his semi (3:52).1 with what he called an easy run. But he had developed a stress fracture in his foot and ran the final in pain: “after about 200 yards in the race I just could not run.” (Athletics Weekly, Dec.27, 1975) He finished dead last with 4:18.2. Had he not been injured, he might well have been able to stay with Ryun on the last lap and perhaps earn a bronze medal. This seems possible in light of his brilliant altitude run in the trials.

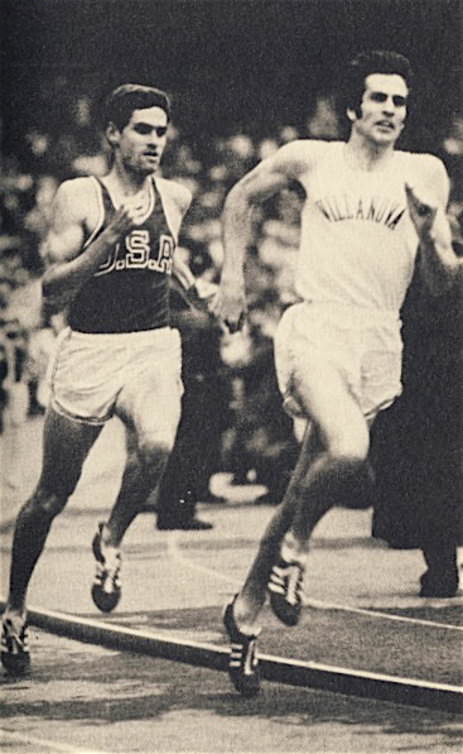

Villanova Sophomore

|

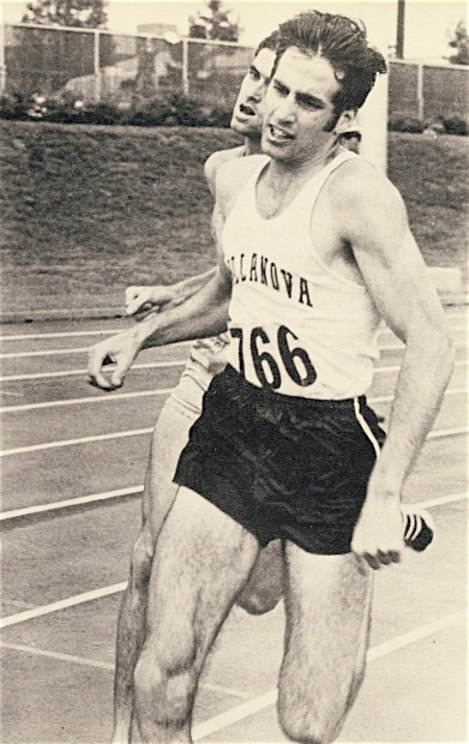

| 1969 NCAA Mile:Jim Ryun, just visible, hanging on "grimly" as Liquori makeshis effort from the bell. |

His foot injury meant that he was unable to represent his university in the 1968 cross-country season. It had healed in time for the 1969 indoor season, and he started with a win in the prestigious Wanamaker Mile (4:00.8). A week later he won a 2 Miles in New York with 8:42.2. His winning ways continued in Knights of Columbus 1,000 (2:08.5), in a 1,500 against Szordykowki of Poland, and in the IC4A mile (4:05.3). His only defeat came in the NCAA indoors when Jim Ryun just got ahead of him at the tape; both were timed at 4:02.6. But it was clear that the fast-improving Liquori was almost ready to replace Ryun as top US Miler.

This happened in the outdoor NCAA Mile. Liquori applied what was to become his trademark tactic of taking off just before the bell: “I can’t outkick Jim for 100 yards, so I’ve got to go earlier,” he explained at the time. (New York Times, June 22, 1969) The tactic worked. Ryun hung on grimly from the bell (3:03.5) and was still on his shoulder with 30 yards to go. But then he gave up. Liquori ran a 3:57.7 PB to Ryun’s 3:59.2. An eagerly awaited rematch at the AAU ended in disappointment as an ailing Ryun dropped out. Liquori made his effort just before the bell again and became American champion with 3:59.5.

First Euro Tour, 1969

Moving to Europe, Liquori won a 1,500 against the Russians (3:40.1) and then ran his best race in the Europe v Western Hemisphere meet, where he was up against Europe’s elite. When he made his effort at the bell, only Tümmler and Arese stayed with him. His sustained effort broke Tümmler on the last bend and Arese in the stretch. It was a prestigious win and a PB of 3:37.2 ahead of Arese (3:37.6) and Tümmler ((3:38.3). Famed British journalist Neil Allen was impressed with his victory: “Liquori was in charge over the whole last lap.” (Times, 31 July 1969) At this high point, another foot injury abruptly ended his season. But what a season! He was the fastest 1,500 runner of the year, American NCAA and AAU champion and the conqueror of both the great Jim Ryun and Europe’s top two milers. Nelson and Quercetani, in their authoritative book The Milers, called Liquori’s miling season the third best ever for a 20-year-old behind Ryun and Elliott. (p. 348)

However, it was ominous that both his last two seasons were terminated by a foot injury. The next year, 1970, was to be no different as his season again ended in August at the height of the European season.

But back to the start of 1970. Liquori was a glutton for competition, so he was back racing indoors in early January. He had two wins in January, including his second Wanamaker victory (4:02.6). An off-night in the Philadelphia Classic left him a full eight seconds behind Keino. In February he won the AAU indoor Mile after some serious physical interaction with Szordykowski: “We exchanged elbows, shoulders and fists on the last lap,” he told The New York Times (Feb. 28, 1970).

Seeking a Competitive Edge

Liquori’s racing tactics need some explanation. It is not surprising that over his career he got into serious physical scuffles with not only Szordykowski but also John Walker and Mike Boit. As a city boy from Newark, New Jersey, he learnt early in life how to stick up for himself. And then his high-school coach, Fred Dwyer, who had been a tenacious competitor himself and had been involved in a serious scuffle with Wes Santee in the 1955 Wanamaker Mile, developed Liquori’s aggression on the track. Liquori wrote that Dwyer “instilled a similar tenacity in me, and…eventually refined my methods, teaching me all the little tricks that he had once used and that are sometimes necessary for mere survival.” (OTR, p. 175) One of those tricks was to purposely box in a rival. Liquori used this trick once too often on John Walker and ended up flat on the ground.

Of course, Liquori cut his competitive teeth on the indoor circuit where runners are much closer together and where the inside position is more important: “If I’m in a crowded race…I just shove ahead and make my presence known, rather than chopping my stride and getting bruised from behind. An elbow in the chest can knock a competitor back…. If you’re rounding a corner and brush a guy’s arm, he’ll lose his balance, he’ll stumble and you can quickly open up a substantial lead…If you nick his heels, you’ll break his concentration, he’ll start worrying about getting spiked.” (OTR, p. 177) After his first European experience as a nineteen year-old, Liquori quickly realized he had to develop his tactics even more. One thing he did to get more respect was to grow a beard in order to look older.

Perhaps his most devious tactic was to arrange with a friend to call out the wrong lap times in order to confuse his opponents. “Many of these tricks are subtle,” he wrote, “and many of them work on the mind.” (OTR, p. 178) As he matured, especially after he beat Ryun in 1971 (“when that passed I finally relaxed. I finally stopped training to beat people.”), he mellowed as a competitor: “I’ve changed with age,” he has written. “I don’t want to alienate people as much anymore; psychologically I now give my opponents less of a hassle. I’m still just as tough when it comes to my personality, but whether I’ve shaken someone else’s confidence, whether I’ve totally destroyed him, is no longer so important.” (OTR, p. 94)

Inconsistent Year

Continuing the 1970 indoor season, he won the IC4A Mile (4:02.1). But in the NCAA indoor he was slowed by a sore leg and lost to Michael, 4:03.1 to 4:03.6. Michael beat him again in the outdoor AAU Mile. And although he won the IC4A Mile (3:58.5) and the NCAA Mile (3:59.9) ahead of Dave Wottle, he was beaten into third in the Compton Invitational Mile by Chuck Labenz (3:59.5). Clearly he was not as dominant as he had been in 1969. His one major victory was in Philadelphia against the great Keino. Keino blasted away after half a lap and at one time had a 30-yard lead. But Liquori kept his head and waited for Keino to blow up. This happened 50 yards from the tape and Liquori went on the beat the Kenyan for the first time. Liquori’s reaction to Keino’s surrender drew many comments. It seems that the ever-competitive American wanted some fight from the Kenyan and that he yelled “Don’t quit on me, dammit!” after passing Keino.

His inconsistent racing form continued in Europe. He won a couple of minor races, but none of the major ones. He ran his 1,500s around 3:40, his best time being 3:39.9, which ranked him 11th in the world for 1970. Then he was injured for the third year in a row. “I ran 15 races in the first month,” he explained. “I lost a lot of them and I was not quite as good as I was the year before…. The main thing I wanted to do was have fun. I had won the important meets in the States, and when I got over to Europe I was really on a sort of a holiday.” (Athletics Weekly, Dec. 27, 1975)

Back Again

His summer injury healed in time for him to do his bit for Villanova in the November NCAA cross-country, where he finished a respectable 9th. In fact, as a Villanova senior, Liquori performed regularly on the track in the spring of 1971. But he also ran some of the indoor meets, winning the Wanamaker Mile for the third consecutive time (4:00.1). For Villanova he won both the NCAA 2 Miles (8:37.2) and Mile (4:04.7) on consecutive nights. He also made major relay contributions for Villanova in the busy spring outdoor season; in fact, he was undefeated in relays in the whole of his Villanova career.

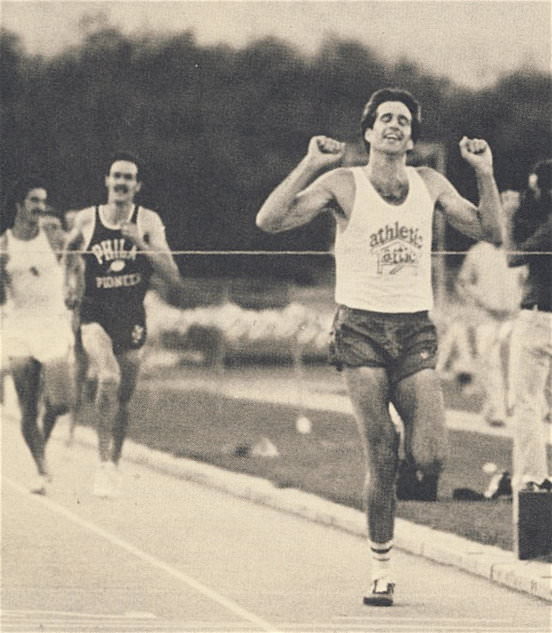

Dream Mile in Philly

|

|

| Miracle Mile in Philadelphia, 1971.Liquori holds off Jim Ryun as they enter the final straight. |

He then began what was his most successful outdoor season. As preparation for a big match-up with Jim Ryun, Jumbo Elliott had him focus on more strength. At this time he was running sessions like 20x440 in 62 with a 60-second rest. He also entered a 5,000 to increase his strength (first in 13:52.3). The May 16 race with Ryun was dubbed the Miracle Mile and lived up to its billing. The race began uneventfully, with the first half run in 2:03.3; then Ryun took charge. But his pace wasn’t fast enough for Liquori, who was soon in the lead. The two passed the bell in 3:00 after a 56.7 third lap. Liquori didn’t like the way Ryun was sitting on him: “I was running scared… I was going to sprint when he pulled up to my shoulder, but he never did until the last 110 yards.” (New York Times, May 24, 1971) Only when they were coming into the final straight did Ryun make his move. Liquori was able to react to Ryun’s challenge and just managed to hold him off by 0.2 of a second. Liquori was timed at 3:54.6, the fastest Mile in the world since 1968. His last 880 was run in 1:51.3 and his last 440 in 54.6. And it was a 2.6-second PB for Liquori. He had again showed what a fine competitor he was. Having led for the last 700 yards and having held off the speedy Ryun, he had shown a fine balance of speed and strength. Afterwards, Ryun told the press that Liquori had run a “smart race.” (NYT, May 16, 1971)

Clearly in the best form of his life, Liquori went on to win the mile in three major championships: IC4A (4:00.4), NCAA (3:57.6) and AAU (3:56.5). A week later he was in Europe running second over 1,000 to the German Kemper. But this year he ran a short European schedule, the highlight being the fastest 1,500 in the world for 1971: a 3:36.0 in Milan, where he again beat the Italian Arese. Another impressive run was a 2,000 victory over Emil Puttemans in an American record 5:02.2. He spent only a month in Europe before flying to Colombia to win the 1,500 in the Pan Am Games (3:42.1).

Injury Nixes Olympics

In the fall of 1971, he was still eligible to run cross-country for Villanova. Although slightly injured, he agreed to run the NCAA race to help Villanova win a third consecutive title. He finished 30th but aggravated his sore foot. This time, his foot injury, a strained instep, was really serious. So he stayed away from the track as much as possible and did a lot of weights and alternative training: “I’ve been working with a guy who is trying to apply training techniques to running that they’ve used successfully for rowing,” he told The New York Times. “The theory is to find other ways of cardiovascular efficiency without running.” (Feb. 4, 1972)

Nevertheless, in early 1972 he did race indoors in a Toronto Mile (third to Arese in 4:09.9) and in a Houston 2 Miles (first in 8:31.6), but then had to withdraw from the AAU indoor. Finally in May he announced that because of a foot injury with a large calcium deposit, he would not be racing again in 1972. This was a huge blow as he had been the world’s fastest 1,500 runner in 1971 and was a favorite for the Olympic gold. He had to watch Vassala and Keino battle for the gold in Munich and wonder whether he would have been in the fight.

Career Choice

With his university degree complete, Liquori might have been expected to follow the general American practice at that time of retiring. Jumbo Elliott, who had coached him for four years, did in fact advise him to retire: “’Quit, he would always say. ‘You’ve had enough of it; now it’s time to work hard at your job.’” (OTR, 103) And Liquori did have business plans in the works. But as he explained in On The Run, “I’m an inherently competitive person, and I recognized soon after I left college that business itself couldn’t fulfill this facet of my nature.” (p. 104)

So he continued competing, but with a different attitude that was more introverted. He had expected that Olympic success would make him financially well off, so he had believed that he had to win there. But now that opportunity had passed: “I finally relaxed. I no longer trained to beat other people. I began preparing myself against myself, I began competing against myself, I began proving myself to myself. I began running for my own satisfaction.” (OTR, p. 96)

Competing Again

After eleven months away from competition, he lined up in a 2-Mile indoor race on January 17, 1973. After finishing second to Ian Stewart, the European 5,000 champion, with a respectable 8:35.2, he was able to report that his foot felt “pretty good.” (NYT, January 13, 1973) Next he won two Mile races but lost one to Prefontaine (3:59.2) and del Buono. Outdoors he wasn’t quite the runner he had been in 1971, perhaps because of his long layoff that left him short of basic conditioning, perhaps because of his move to Florida, perhaps because of the hard work developing both his retail business and his career as a sports commentator. He was able to run under 4:00 but said he lacked speed. In May, Popejoy and Wottle beat him in a Mile; in June he ran well in the AAU with 3:56.9 but ceded first place to Hilton. In July he ran second (3:41.9) behind Wottle (3:41.7) representing the USA against the USSR.

So 1973 wasn’t one of Liquori’s best years. Nor was 1974: “In 1973 and 1974 I was just a business man,” he later told Alastair Aitken. “I wasn’t a runner although I kept my hand in and managed to run 3:56 both years.” (AW Dec 27,1975) And both seasons were spoiled by health problems. He was having to avoid speedwork because of his chronic foot problem. And in June 1974, he suffered from a damaged hamstring and from a blood problem after taking a medication for an achilles injury.

In the 1974 indoor season, he found his match in Tony Waldrop. Waldrop beat him in the Millrose Games and again three days later. But ever the competitor, Liquori was pushed by Waldrop to record his fastest indoor time ever: 3:58.5. His 1974 outdoor highlight was a 3:56.8 Mile in Oslo in August. Also significant was his 5,000 performance in the AAU—third in 13:40.6. Significant because the 5,000 was soon to become his main event.

Training

In fact, he was already training more like a 5,000 runner, clocking an average 100 miles a week. Later in 2006, he admitted, “I probably shouldn’t have been running the Mile. I was running the wrong event for most of my career. I was really more geared to the 5,000 because of the amount of long distance that I did run.” (Bob Kopac, “Chat: Marty Liquori,” Runner’s World, Sept. 14, 2006) When asked if he had ever over-trained, he answered with a laugh, “All the time. All the time.”

Although it provides no training schedules, Liquori’s book leaves the impression that he was a consistently hard trainer. However, he did learn to taper down before competition: “What I found out over the years was American runners didn't know how to rest enough. They thought if they rested for three days before a race, that was a rest. What I know was, it took almost a month of detraining--I'll say that again--a month of detraining before you were ready to set a personal best. Most people don't have the ability to say ‘I'm going to train 20 percent as much as I did for the rest of the year.’ They just can't cut back.” (Kopac, “Chat: Marty Liquori”)

Return to Top Form

After two erratic and transitional years, Liquori made huge improvements in 1975, with world rankings of 11th in the 1,500 and 5th in the 5,000. But his best run came early in the outdoor season when he ran his all-time Mile PB of 3:52.2.

The year started off well with three indoor wins in January, one over Prefontaine (3:57.7 to 3:58.5), one over Cummings, and a 2 miles in 8:40.8. But for the Wanamaker Mile, he was suffering from an infected tooth and could only make fourth as Filbert Bayi won in 3:59.3. He soon recovered, and in February he trounced his successor at Villanova, Eamonn Coghlan, 3:55.8 to 4:00.4. The see-saw season continued with a loss to Walker and Dixon over a Mile. Liquori was running as well as he had ever run indoors, but he was now encountering a new breed of milers, Bayi and Walker especially, who weren’t afraid to go out much faster that Liquori was used to: “When I was running as No. 1 in the world in 1969,” he told Alastair Aitken, “there was only one time that whole year that I went by three-quarters faster than 3:00.” (AW, Dec. 27, 1975)

Miracle Mile #2

|

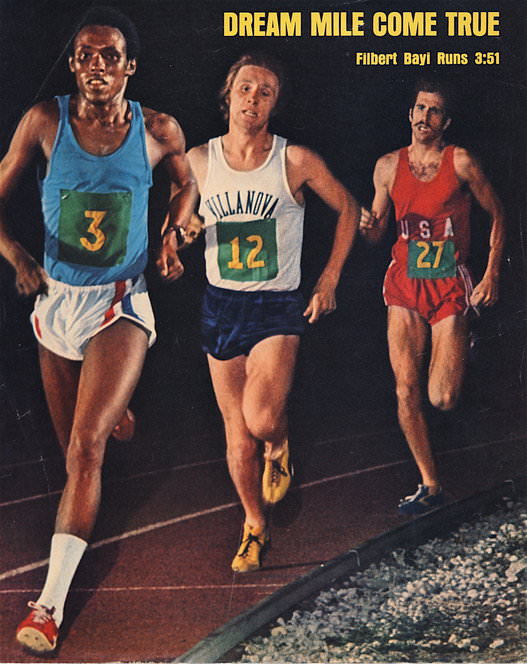

| Sports Illustrated cover: Liquori trails Filbert Bayi and Eamonn Coghlan in the Jamaica Mile. |

After his indoor losses to Bayi and Walker, he badly wanted a rematch when the outdoor season began. So he jumped at the chance to run against Bayi again in the Martin Luther King Games. He went to Jamaica fairly confident he could match his 3:54.6 PB from four years earlier. Bayi was the main attraction for the Miracle Mile, as it was billed, but Eamonn Coghlan and Rick Wolhuter were also major opponents for Liquori.

Well aware of Bayi’s habit of starting fast, Liquori let the Tanzanian get well ahead in the first 56.9 lap and didn’t try to get near the lead until the halfway point, which he reached in 1:58.4, some 10 yards behind the Tanzanian. While Coghlan used a lot of effort on the third lap to catch Bayi, Liquori ran steadily to keep the leader within a reasonable distance. At the bell it was Bayi (2:55.3), Coghlan (2:55.7) and Liquori (2:56.2). The youthful Coghlan was running the race of his life, and he hung on to Bayi round the back bend. When Bayi escaped from him, Liquori moved up the Irishman’s shoulder and passed him on the crown of the last bend. Liquori was now only four yards out of the lead, but Bayi still had some gas in his tank and was able to move away a little in the last 100. At the tape it was Bayi 3:51.0 (a world record), Liquori 3:52.2 and Coghlan 5:53.3. Behind Bayi’s WR, Liquori had run the fourth fastest Mile ever and had knocked 2.4 off his PB. He was back at the top of his game and ready to take on the world in Europe.

Europe Again

Before Liquori left, he did some more racing while nursing a slight groin injury. Coghlan beat him in a Mile at Villanova (4:01.2 to 4:02.5) and then Waigwa beat him in a Berkeley race. Because of his groin problem, he ran the 5,000 instead of the 1,500 in the AAU and took the title with a 58.8 last lap (13:29.0). He was in full control throughout, leading for the first mile to ensure a fast time, and then making his effort with 600 to go.

|

| Stockholm Mile, 1975: Liquori (65) and Dixon scuffle on the outside and Walker (60) and Garderud scuffle on the inside. |

Fortunately his groin healed, and for the first time he was able to race injury-free for over two months in Europe. Just a week after the AAU he ran in the Helsinki World Games. Still somewhat jetlagged, he was up against the great New Zealand duo of John Walker and Rod Dixon. Walker, with a 1,500 time of 3:32.5 (worth under a 3:50 Mile), was disappointed in not having Bayi to run against. Dixon with a 3:33.89 in 1974 was almost as fast as his countryman. It was a tough first race in Europe for Liquori, and not surprisingly he finished third in 3:37.96, 1.65 seconds behind Walker and 0.51 behind Dixon. “I had the worst last quarter of my life,” he told Chris Brasher (SI, Sept. 15, 1975)

Four days later he was in better shape for a rematch in Stockholm over a Mile, “the greatest mass Mile ever run,” according to Nelson and Quercetani (The Milers, p. 396) In the early stages he hung back, but well before the bell (2:57.7) he went into the lead. He was at full speed on the back stretch, with the two Kiwis chasing. It was not until the final straight that Walker caught him. This time he was second but no closer to Walker: 1. Walker 3:52.2; 2. Liquori 3:53.4; 3. Dixon 3:53.6. Both Walker and Liquori were frustrated that the world number one, Bayi, was absent. “I was ready. I’m sure it could have been under 3:50,” bemoaned Liquori to Chris Brasher. “I came her to [decide] what I should run in the Olympics next year—the 1,500, knowing that I can beat Bayi, or the 5,000 knowing that I can’t.” (SI, July 14,1975)

|

| John Walker wins the Stockholm Mile from Liquori and DIxon. |

On July 17, Liquori finally beat Walker in a 2 Miles, again in Stockholm, with an American record of 8:17.2. Walker had entered the race to attack Brendan Foster’s 8:13.8 world record and had arranged for a pacemaker. Thus the pace was very fast—4:06.3 at one mile. Walker then took the lead, followed by Dixon. As he often did, Liquori hung back about 10 yards. By the time they hit 2,000m, Liquori and Garderud were up with the two leaders. And when Walker, who hated leading, faltered with 500 to go, Liquori made his move. Soon he was 5 meters ahead and over the last lap he increased his advantage to 3.5 seconds over Walker.

A week later in Gateshead, the Kiwi got his revenge after Liquori tried to box him in behind Mike Boit on the last lap. In his third race in six days, Liquori had no answer to both Walker and Boit in a slow Mile: 1. Walker 3:57.6; 2. Boit 3:58.2. 3. Liquori 3:59.5. In his hectic racing schedule, Liquori also tested himself at 5,000. After two races around 13:30, one of which was a win in the British AAA Championships, he finally dropped his time to 13:23.6 in running second to Dixon in Gothenburg. This ranked him sixth in the world for 1975 and placed him within reasonable distance of the leader Puttemans (13:18.6). His last race was a 3:55.2 Mile in London behind Walker, Boit and Dixon. Here he felt a twinge in his hamstring and probably realized he had pushed himself enough on this tour. His two months of competition had given him a strong message that his Olympic chances looked better in the 5,000. Still he hadn’t yet decided.

Olympic Year

After a confidence-boosting 10th place finish in the November AAU cross-country, Liquori began his Olympic year with a virus that pretty well put him out of the indoor season. He did run one Mile race in January, finishing third to Waldrop and Malan. His Olympic prospects looked better in April when he won an outdoor 5,000 at Mt Sac in 13:33.6 with a 57 last quarter. At that time, he announced that he would focus his season on two races, the US trials and the Olympics.

Later, he also decided to run the AAU 5,000 two weeks before the US trials, in which he would also contest the 5,000. “I don’t have the kick I used to have,” he told Sports Illustrated in explaining his choice of the 5,000 over the 1,500. “But I’m stronger.” (May 3, 1976) The AAU race was to be his undoing, for just before the AAU he slightly damaged his hamstring after stepping in a small golf-course hole. In the race his leg felt fine and had opened up a 15-yard gap on the back stretch of the last lap: “But then, when I went into a full kick for the final 200 yards, it just went…. All I could do was just stagger in.” (OTR, p. 8) He did manage to finish in second place with 13:41, but a minor hamstring injury had become a major one.

Another Olympic Setback

In the US trials two weeks later, he had to drop out halfway through his heat. He had given himself a 20% chance of making the team in view of his injury. Liquori still went to the Montreal Olympics--but as a TV commentator. Despite this huge disappointment, he wasn’t yet finished with track: “I didn’t want to stop running. I didn’t was to leave the American people with the image of Marty Liquori as a loser…. [So] I was faced with making a comeback, which I had already done a couple of times…. I set myself a goal. I didn’t psych myself all up and say to myself, ‘Well, I’m going to show the world.’ I just decided I wanted to win one race, the most important race in America during the entire year, and that was the [AAU] outdoor nationals.” (OTR, p.25)

In his book, Liquori described the changes in his life as he began training more seriously than ever: “Carol [his wife] knows that I won’t miss a single workout, that I’ll have little energy around the house, and that I won’t be bothered with trivial concerns. The people at my office know that I’ll be arriving there at eleven each morning instead of ten, and that I’ll be leaving at exactly four each afternoon, instead of remaining later to clear up the day’s work. I’ll refuse speaking engagements, I’ll leave Gainesville only for a dire emergency, I’ll follow my own training program, and I’ll never stay out late simply for enjoyment. ‘Live like a clock,’ Jumbo always told us, and I now follow that advice.” (OTR, pp. 210-11)

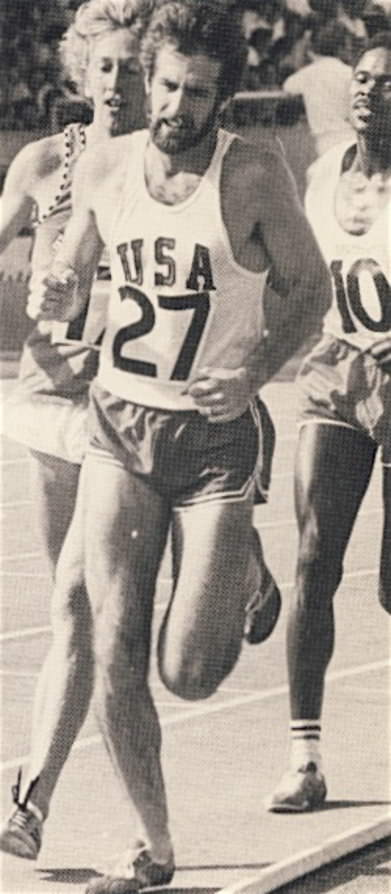

Businessman and Athlete

|

| 1977. Achieving his final goal:an AAU title. |

By the end of November he was in reasonable shape, finishing 62nd in the 1976 AAU cross-country. He trained through the 1977 indoor season and ran himself into competitive shape with some minor outdoor races in Japan. First, he ran fourth in a 1,500 (3:51.8). After another fourth in a 5,000 (14:13.8), he clocked an encouraging 3:40.7 to win another 1,500. Liquori was offended when this excellent time was not covered by Track & Field News. He discovered that the “Bible of the Sport” considered the time a mistake and had discounted it. Clearly the general opinion was that he was finished as a top-class runner. After this snub, Liquori’s pride made him even more determined to achieve his final goal of winning an AAU title. A month before the meet he ran a 3:59 Mile time-trial. This encouragement was shortlived as Nick Rose then beat him by 30 seconds over 5,000 in the Muhammad Ali Meet. His time, admittedly on a cinder track, was only 14:07.2.

By now he felt he was a “peripheral figure” in the US track scene: “People see me but discount me.” Partly this was because he had kept quiet about his hard training and his very serious intention to win the AAU 5,000. On the day of the race, he worked in the ABC commentary booth from 11:00 to 6:00. Ironically the race was on the same track where he had pulled his hamstring before the Olympics. He ran the same race as he had done then, biding his time in the early stages and making his effort with 500 to go. As in 1976 he had a 15-yard lead on entering the straight, and this time he “moved easily” into the tape. His goal was achieved; his time 13:41.6. On his last lap he had raised his fist in defiance as he passed the spot where his hamstring had torn the year before.

Still Hungry

Of course, this would have been the perfect end to his career, but the 27-year-old still wasn’t finished. With such a solid base of training behind him, he went off to Europe. He went partly because his AAU win had qualified him for the World Cup in West Germany. Six weeks later in Nice, still jetlagged and not having raced since his AAU victory, he won a 1,500 in 3:38.6 after a slow first 800 in 1:59. Steve Scott and Mike Boit trailed behind. Then it was on to Zurich for the 5,000 in the Weltklasse, where he was up against the new WR holder Samson Kimombwa as well as Dick Quax, Henry Rono, Miruts Yifter and Frank Shorter.

Although this was his first international 5,000 for over a year, he felt comfortable with the leaders. With two laps to go, though, he was back in fifth, 20m behind the lead group. On seeing Yifter look back at him, Liquori took heart, and knowing he would be racing against the Ethiopian in the World Cup decided to go after him and try for third place. In the next 400 he made up five meters on the lead group, and when he passed the bell he heard the surprisingly fast time of 12:19. If he could run the last 400 in 60 he would break the American record: “I put my head down, I accelerate noticeably and I pass them all as we circle the turn. I have 20 yards on them by the end of the backstretch, and now I’m thinking world record, and I search for more.” (OTR, p.281) Liquori held on to run a 57 last lap and break the American record with 13:16, just three seconds short of Quax’s recent WR.

This completely unexpected breakthrough was a just reward for his year of hard work after missing out on the Montreal Olympics. “I feel reborn, resurrected, and I can’t sleep,” he wrote of his reaction. (OTR, p. 282) And there was still the World Cup in Dusseldorf ten days ahead.

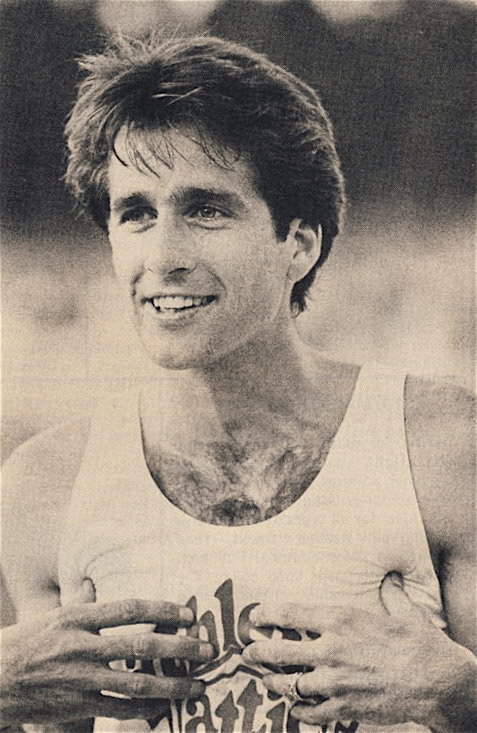

Even Better

|

| Liquori leads Nick Rose. |

Apart from Yifter, Liquori also had to deal with England’s Nick Rose and the home favorite Fleschen. And it was Fleschen who took the field through the first half of the race at WR pace. With six laps to go, Rose took over and subjected the field to bursts that took them ahead of WR pace. Liquori decided not to try to stay with Rose. It was a risk, but the risk made sense: “I thought Rose’s bursts would take it out of everyone who went with him,” he told Kenny Moore. I paced myself to what I thought would be the world record and took a calculated risk that I’d be back up there.” (SI, Sept. 12, 1977) Rose continued surging for four laps with Yifter and the Aussie Fitzsimmons on his tail. The trio were 40 yards ahead of Liquori with two laps remaining. In the next lap he got within 10 yards. Into the last lap, he caught them on the back bend and was ready to steam by. But Yifter was quick to react to Liquori’s presence and really took off. Liquori passed Rose quickly and then gradually closed the gap on the back stretch. But as soon as he has caught Yifter, the Ethiopian sprinted hard again. Liquori was able to hold him but not pass him. Yifter, despite his lead at the bell, had to run a 53.8 last lap to hold off Liquori. 1. Yifter 13:13.8; 2. Liquori 13:15.1. Another American record, another PB.

“Retire? Hell, No”

After such a great summer of unexpected successes, how could he retire? Despite his business obligations and commentating duties, he could still find time to train. “You have to keep saying ‘I don’t want to be 40 and know I went 9/10ths of the way,’” he told Tom Jordan (Track & Field News, May, 1978)

Thus in the spring of 1978 he was, according to Track & Field News, training better than he had been in years (115 to 120 miles a week), preparing to run 13:10.” (June 1978, p. 58) However, in April he got a shock as Henry Rono reduced the 5,000 WR from 13:13 to 13:08.4: “The record is a real challenge now,” he admitted. And it did indeed prove to be too much of a challenge. His 13:16.10 in Stockholm on July 4 was the closest he got.

This fine 5,000 time was not quite Liquori’s last hurrah. After a fairly busy 1979 indoor season, where he ran 4:03 and 4:01.6 and won the AAU 3 Miles title, he ran 14:00.6 for 5,000 outdoors. He had planned for 1979 to be a fallow year, for he wanted to compete in the Moscow Olympics. And he got himself into good shape for the trials. Then his body let him down again: after running third in his heat with 13:43.59, he retired injured. As it turned out, of course, for political reasons the American team never went to Moscow. Game over.

Conclusion

|

Marty Liquori’s running career is a good example of how much it took to be a top world-class runner in the late 1960s and the 1970s. There is no doubt that he was up there with the likes of Ryun, Walker, Keino, Bayi and Coghlan. Like these champions, he was blessed with unusual talent; like these champions he pushed himself to the limits in training. And as his university coach Jumbo Elliott has pointed out, he had competitive talent too: “Marty has the talent, he has the strength, and he’s a great competitor. He loves to win, and he has always been quite confident.” (Jim Dunaway, “Will the Real Marty Liquori Please Stand Up.” Track & Field News, Dec. 1971) Neil Amdur, who covered the early career of Liquori for The New York Times was also aware of Liquori’s confident and competitive personality, seeing him as “an extrovert who has been called confident, cocky and brash depending on how his personality strikes an interviewer.” (June 26, 1969) Above all it was his intense competitiveness that enabled him to achieve so much despite his injury setbacks. And this competitiveness combined with intelligence gave Liquori the self-discipline to achieve many of his goals.

Although he could compete on equal terms with the world’s best in Europe, many of his achievements took place in the US: five outdoor AAU titles, three NCAA titles, six IC4A indoor and outdoor titles. He also ran 26 four-minute Miles, 14 sub-3:42.2 1,500s, and PBs of 3:36.0, 3:52.2, 8:17 and 13:15.06 for the 1,500, Mile, 2 Miles and 5,000. All of these PBs except for the Mile were American records. The sad part was that he did not get a chance for Olympic glory. He ran injured in the final of the only Olympics he competed in, and injuries kept him out of the two Olympics where he could well have won medals.

There is no doubt that injuries seriously affected Liquori’s career. However, he has denied this: “The public perception is that I’m frequently injured, which is the biggest misconception regarding my running career. I have, in fact, been quite lucky, and in the 15 years that have passed since I was initiated into this sport, there have been perhaps only ten months when I wasn’t able to compete.” (OTR, p. 110) Ten months over 15 years doesn’t sound like a lot, but it’s clear that injuries severely damaged his career, often coming at crucial times. Of course all top runners have to deal with injuries, but Liquori had more than his fair share. His competitiveness, seen from today’s perspective, was a double-edged sword: while he benefited from this quality enormously in conditioning and in competition, it also led him to compete too much. For too many years he tried to be in track-racing condition for eight or nine months a year, running because he did both indoor and outdoor seasons. No wonder his legs tended to break down at crucial times.

28 Comments