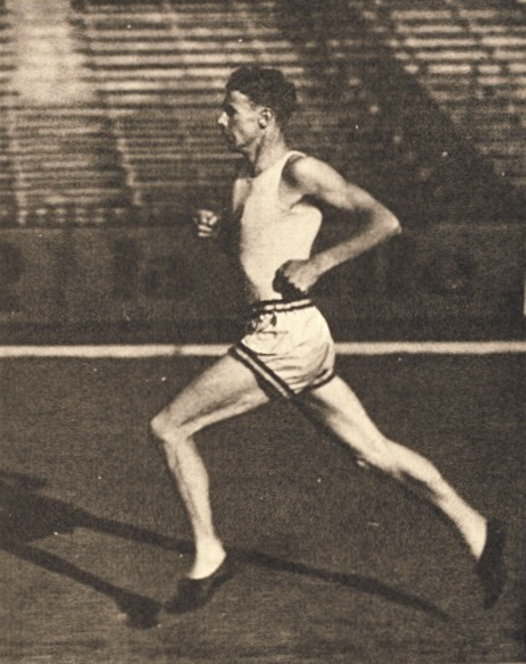

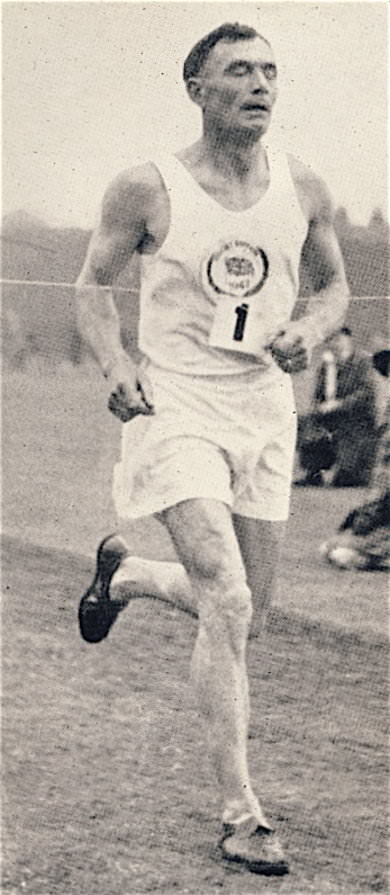

184 years of talking – Parrot fashion – about someone running a four-minute mileby Bob Phillips When I was researching a book I wrote to mark the 50th anniversary in 2004 of the first sub-four-minute mile I became intrigued by the ”near-misses” and the “might-have-been” – the performances by athletes who could perhaps have preceded Roger Bannister by a few years, or even more, had they been given the right opportunity. There are a surprisingly large number of them, and I came to the conclusion, for example, that not nearly enough credit had been given to the fastest mile run in the years before World War II. Contrary to what you might suppose, that was not the official World record of 4:06.8 by Great Britain’s Sydney Wooderson in 1937 but the 4:04.4 indoors by the USA’s Glenn Cunningham the following year.

Los Angeles and Paris will bid on 13 September to stage the 2024 Olympics. The first Games that were held in Paris, in 1900, were prolonged and often chaotic – in particular, the marathon, which was to be highly influenced in its formative years by British & Irish involvement. Pandemonium in Paris. “Preposterous”, says the perplexed Mr Poolby Bob Phillips The marathon race at the first Modern Olympic Games of 1896 in Athens was a rip-roaring success, and the main reason was that it was won by a Greek, accompanied for the last few yards by royalty, no less, to the immense pleasure of the 40,000 or so onlookers packed into the stadium and many thousands more on the surrounding hill-sides. The home victory was certainly helped by the fact that the only competitors who had any experience of marathon-running were the Greeks themselves, who had qualified via two trial races, and a lone Hungarian, whose athletics administrators had also been sensible enough to stage their own eliminator to see if any of their countrymen could last the distance.

We all know that the marathon is 26 miles 385 yards. But why? Whose idea was it?by Bob Phillips Pheidippides didn’t do it. Or if he did, the Ancient Greek press corps were a bit slow on the uptake, and there could only have been a blithe disregard for any sort of reasonable topicality among the scribes of the day. Treating deadlines with disdain, one of the most widely read columnists of 2,400 years or so ago, Herodotus, only picked up on the story some three or four decades later. Plutarch – even more renowned among his avid readership – waited half-a-millenium before putting a pen to paper, or more precisely a split reed to papyrus/ Maybe he was short of anything newsworthy that week and so revived a vaguely remembered myth instead. Even in the 1st Century A.D. when Plutarch was scribbling away (or should that be “scratching” away?), publicity for Greek war messengers was still a sensitive subject because they had often been suspected of being deserters.